A Guide to Miles Davis

Miles Davis' remarkable collection of music exemplifies his ever-curious and inquisitive nature, with these ten pieces highlighting his impact that extends beyond just jazz.

Trumpeter Miles Davis, a maverick and icon, was instrumental in shaping the trajectory of jazz and popular culture in the 20th century. His career spanned five decades, during which he played the trumpet with an introspective style that was both personal and intimate, often using a stemless Harmon mute to enhance his sound.

Davis was not just a trumpeter but an artist who constantly evolved. He transitioned from bebop to modal jazz in the '60s, then moved on to electrified funk and fusion in the '70s, incorporating wah-wah pedal effects into his trumpet playing. His influence on jazz is undeniable, with groundbreaking albums such as Birth of the Cool (1957), Kind of Blue (1959), Sketches of Spain (1960), and Bitches Brew (1970) setting new directions for the genre.

In addition to his playing, Davis made significant contributions as a bandleader. He worked with talented sidemen and equally innovative collaborators, including John Coltrane, Herbie Hancock, Bill Evans, Wayne Shorter, and Chick Corea. Even though Davis is primarily associated with jazz, his music transcends this genre. His influence can be seen in various musical styles, from electronica, funk, hip-hop, rock, and more.

Throughout his life, Davis adopted an open-minded approach to jazz that was praised and criticized. The flamboyantly dressed leader who frequently used a wah-wah pedal and an electric keyboard in his later years bore little resemblance to the young musician who admired Charlie Parker's bebop style. Despite this transformation, Davis played a crucial role in making jazz more accessible to the public, reversing the trend set by Bebop towards a less commercial appeal. Regardless of his stylistic changes and experiments, Davis never lost his ability to play moving solos that resonated with his fans and showcased his deep connection with tradition.

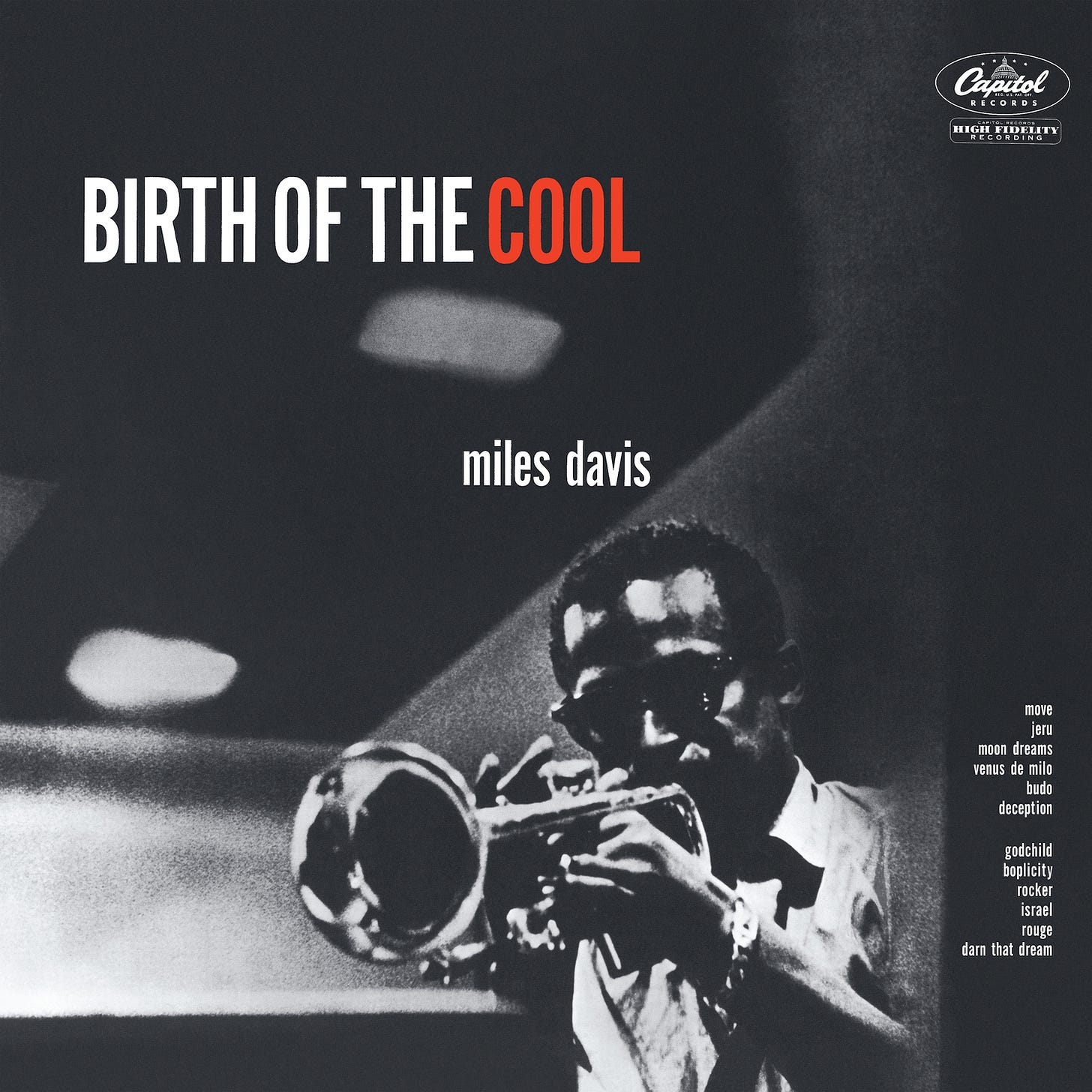

Birth of the Cool

In a departure from the frenetic energy of be-bop, 23-year-old Miles Davis led the way in introducing a novel form of jazz, christened “cool.” This new style, emerging from three distinct recording sessions, offered a slower tempo and a meticulously crafted, harmonious, and ethereal sound. While this shift didn’t find universal acclaim among jazz aficionados—some took issue with its perceived emotional detachment and its nods to classical music—it nonetheless marked a significant evolution in the genre.

The ensemble behind Birth of the Cool was nothing short of remarkable, featuring a roster of musicians like Lee Konitz, Gerry Mulligan, Junior Collins, Sandy Siegelstein, Bill Barber, J. J. Johnson, Kai Winding, Mike Zwerin, Al Haig, John Lewis, Joe Shulman, Nelson Boyd, Al McKibbon, Max Roach, Kenny Clarke, and Gil Evans. Davis led a nonet by escaping the traditional formats of a big band or a small ensemble. The focus was on intricate arrangements explicitly crafted for him by Gerry Mulligan, Gil Evans, and John Lewis. This groundbreaking approach to music arguably catalyzed some of the most transformative shifts the jazz genre has ever seen.

Relaxin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet

Emerging from two recording sessions on May 11 and October 26, 1956, Relaxin’ is a product of a group that would later gain recognition as Miles Davis’ inaugural quintet. Alongside Davis’ trumpet, the quintet featured John Coltrane on saxophone, Red Garland on piano, Philly Joe Jones on drums, and Paul Chambers on bass. These sessions gave birth to Relaxin’ and created three other distinguished works: Steamin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, Workin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet, and Cookin’ with the Miles Davis Quintet. In the context of post-bop music, this album has gained a near-sacred status.

The album’s six tracks diverge from the high-energy atmosphere commonly associated with be-bop. Instead, they offer a collection of pieces the quintet had been perfecting through live performances and captured with precision in the studio. The musical selection is impressive, including compositions from Broadway luminaries such as Richard Rodgers with “I Could Write a Book,” Jimmy Van Heusen’s “It Could Happen to You,” Harry Warren’s “You’re My Everything,” and Frank Loesser’s “If I Were a Bell.” Utilizing these well-known, powerful tunes, the quintet crafts extraordinary musical dialogues that captivate the ear.

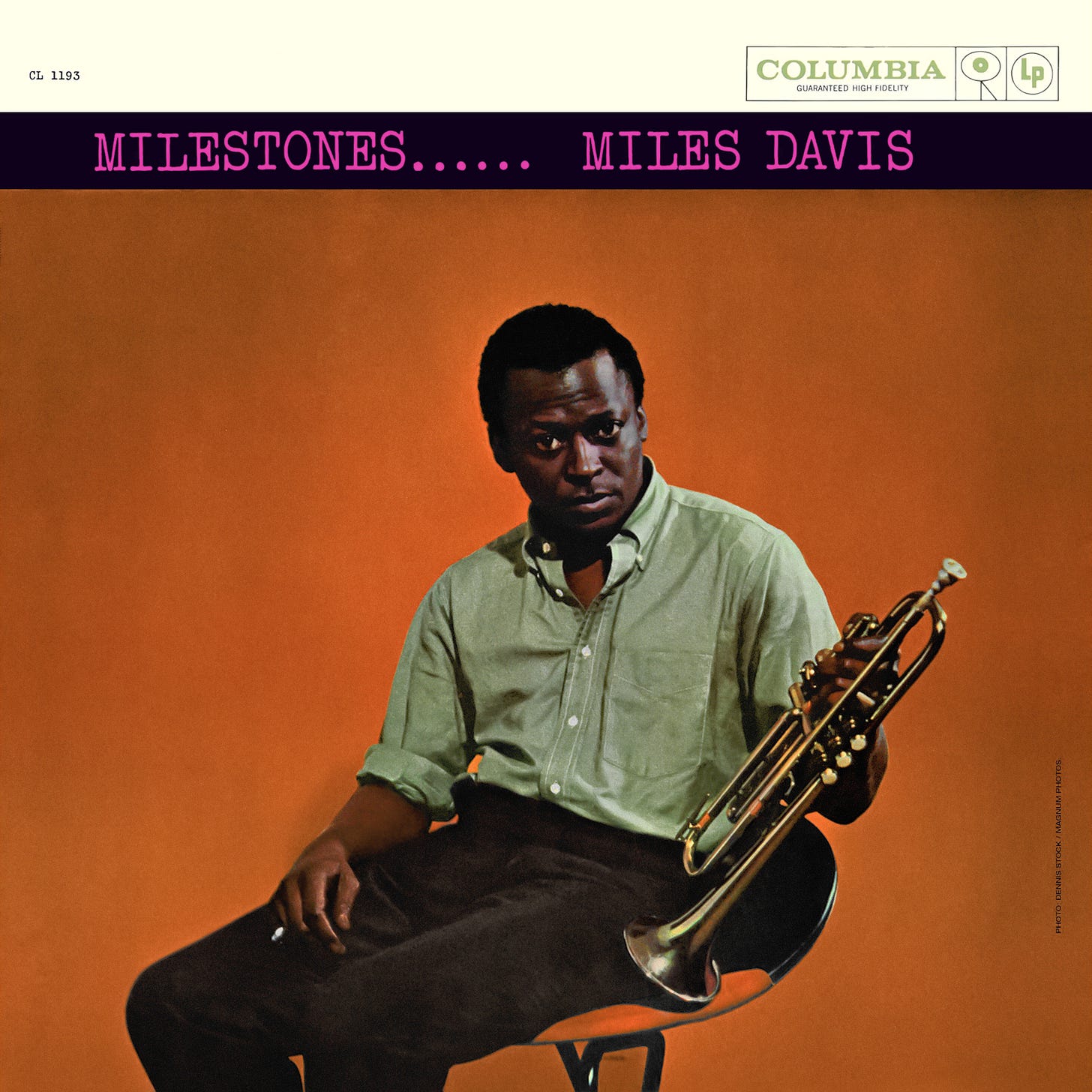

Milestones

In his autobiography, Miles Davis emphasized the unique quality of the album Milestones, recorded at Columbia Studios in New York. The album was groundbreaking, not just for its musical compositions but also for adding a sixth member to the ensemble. This new dynamic proved to be a critical factor in the album’s success. The album features a roster of talented musicians: John Coltrane, Red Garland, Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones, along with the extra participant. This ensemble, led by Miles Davis, produced an album that was nothing short of groundbreaking. The distinct styles of the two saxophonists, in particular, added a unique flair that catalyzed the album’s distinctiveness.

One of the standout tracks on the album is the title track. This historically significant piece showcases each musician hitting just the right notes. In this composition, Miles Davis took a bold step by liberating himself from the piano’s harmonic limitations, allowing for a more free-form expression. John Coltrane’s performance is also noteworthy, adding another layer of brilliance to the track. Another intriguing aspect of Milestones is the track “Sid’s Ahead.” In this piece, Miles Davis takes over the piano after Red Garland abruptly leaves the session, angered by a comment from Davis. This unexpected turn of events adds another layer of complexity to an already exceptional album.

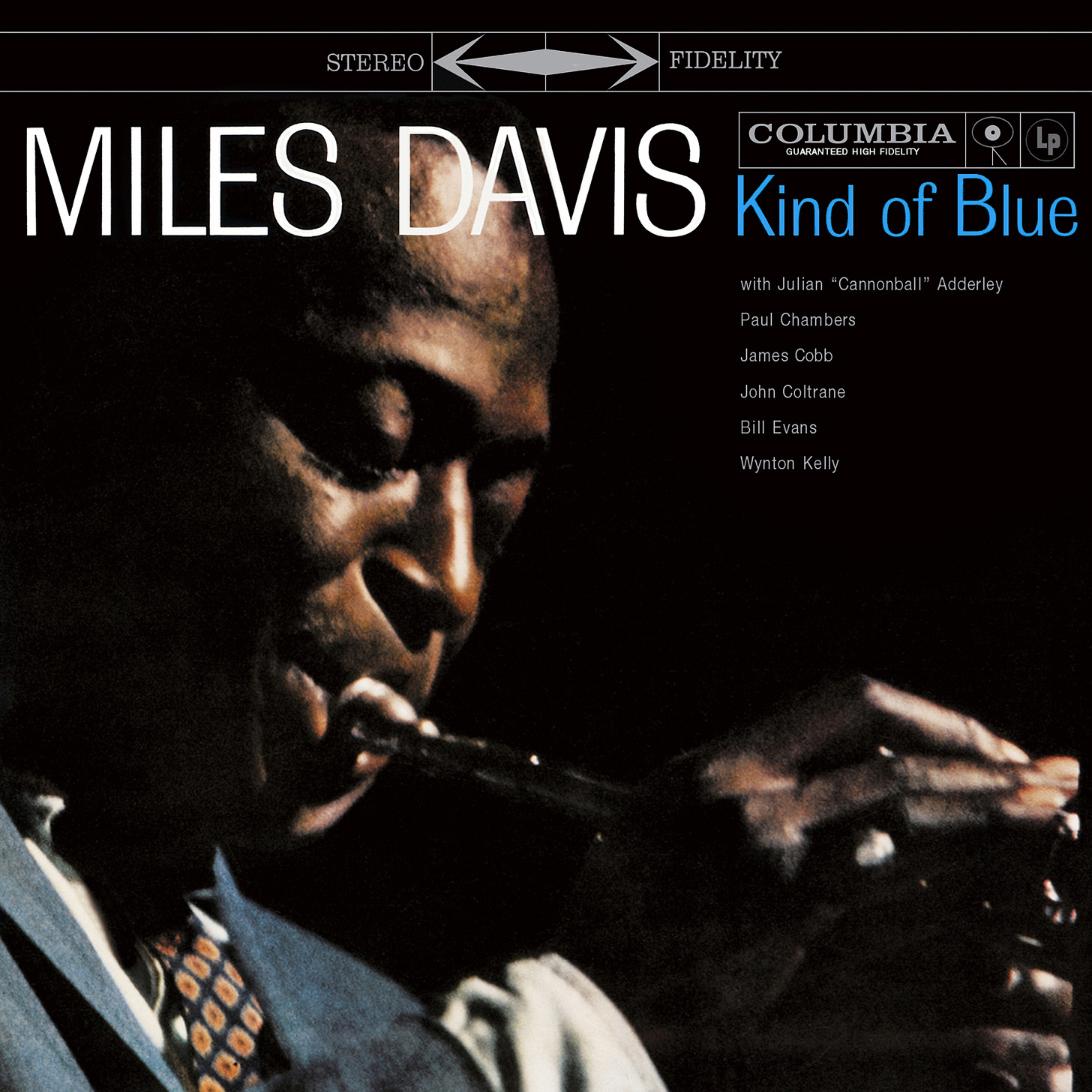

Kind of Blue

The album Kind of Blue is often celebrated as the pinnacle of recorded music. Interestingly, although Miles Davis is the face on the album cover, he was quick to credit the influence of Bill Evans’ style in shaping this iconic work. Evans, who had already gained attention in jazz circles with his first two albums—1957’s New Jazz Conceptions and 1959’s Everybody Digs Bill Evans—found what could be considered his magnum opus in Kind of Blue. The album, a joint effort featuring saxophonists John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley, double-bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb, marked a departure from the harmonic complexity of hard bop. Instead, it ushered in a modal jazz approach that provided a broader canvas for improvisational creativity.

Evans’ influence extended beyond just style; he also introduced Davis to the works of classical composers like Bartók and Ravel, who utilized modal structures. Drawing from his grasp of the blues’ modal elements, Davis, in collaboration with Evans, developed a set of basic themes. These themes were deliberately kept from the other musicians until they arrived at the recording studio on March 2, 1959. Davis was intrigued by the idea of capturing the spontaneous interactions among his band members. For the first time in his career, he found a pianist who shared his appreciation for minimalism, space, and silence. This mutual understanding is particularly apparent in the album’s closing track, “Flamenco Sketches,” which was penned by Evans himself.

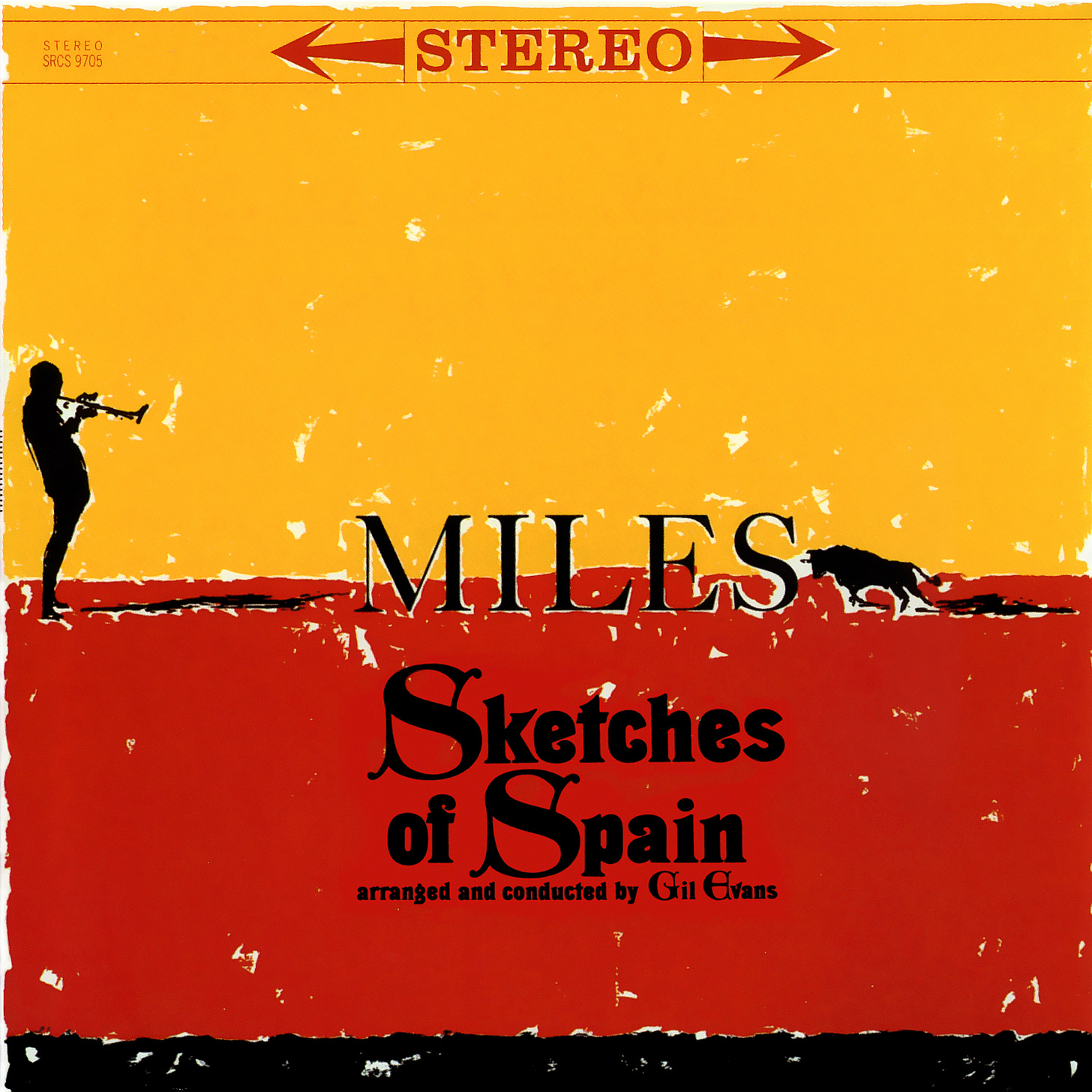

Sketches of Spain

Miles Davis was consistently inventive, constantly surprising audiences with the diversity of his repertoire. Sketches of Spain was no different. It came to life during three recording sessions, on November 15 and 20, 1959, and March 10, 1960. With his saxophonists John Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley having departed, the trumpeter collaborated with Canadian pianist and orchestrator Gil Evans, a previous collaborator on Birth of the Cool, Miles Ahead, and Porgy and Bess. Intrigued by the Concierto de Aranjuez, a composition by Joaquín Rodrigo from 1939 which he heard at a friend’s place, Miles desired to base his new album on this significant classical work, along with pieces by Heitor Villa-Lobos and Manuel de Falla.

Sketches of Spain, released on July 18, 1960, is an undisputed classic. Gil Evans’ arrangements transformed the Concerto into a jazz orchestral piece with unique musical hues. Elements of Andalusian folklore, flamenco, and other Iberian musical codes are beautifully integrated. As director/sound director, Evans skillfully manipulates the dramatic staging and lyrical melodies. Miles offers some of his most elegant and poetic phrases amid this vibrant yellow backdrop and this unique reinterpretation of traditional Spanish music.

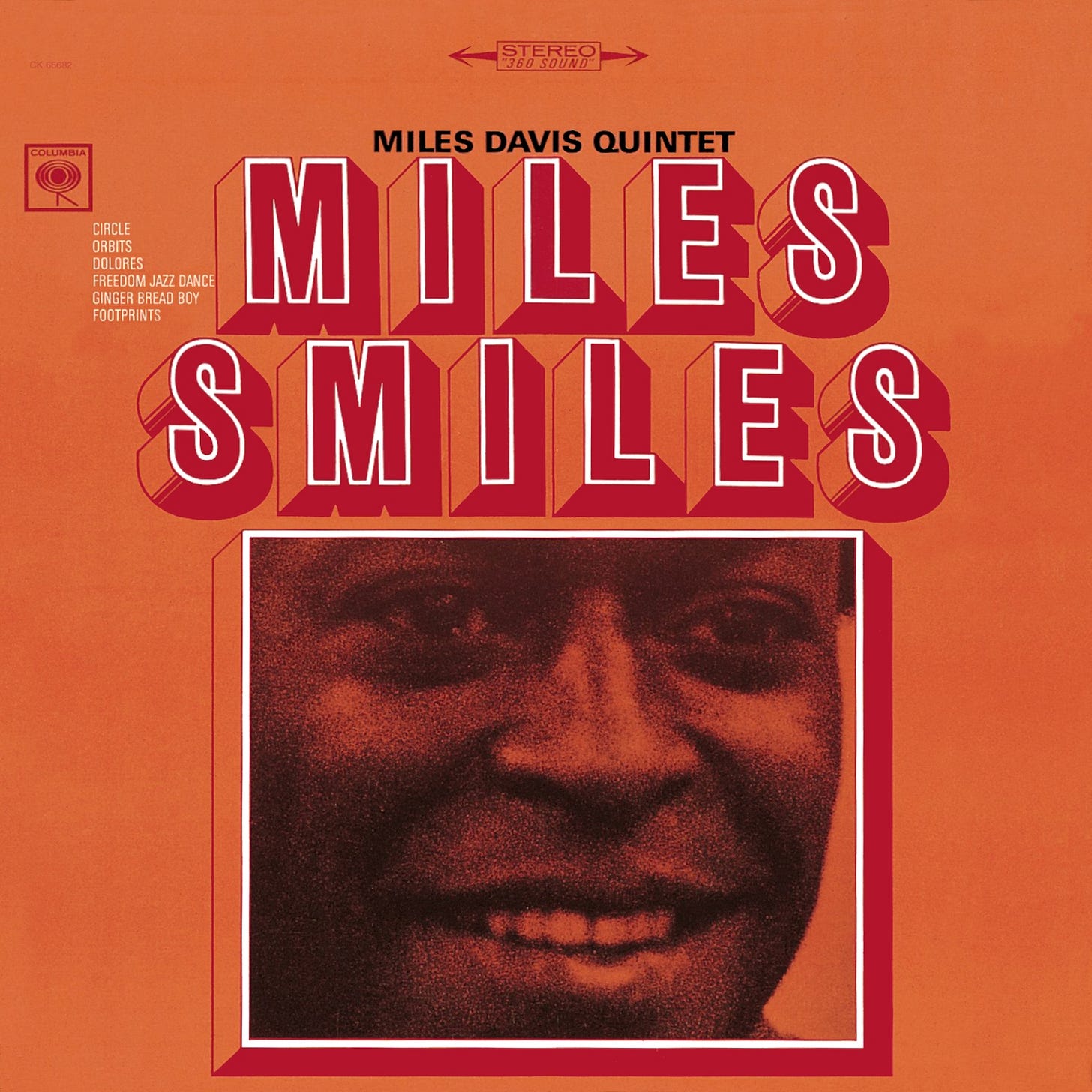

Miles Smiles

With his renowned second quintet, Miles Davis led one of the most creative and influential bands of his career from 1964 to 1968. This group consisted of young talents, now legends: pianist Herbie Hancock, saxophonist Wayne Shorter, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams. This quintet recorded E.S.P., Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky, Filles de Kilimanjaro, The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965, and Miles Smiles—recorded on October 1966 and released in February 1967.

With this second quintet, Miles took a different approach to free jazz and wanted to experiment uniquely with his new band. Each improvisation radiates a raw freshness, where rhythms intertwine, and sequences complete swing transition to floating interludes. Predictability is non-existent. Particularly noteworthy is Miles’ playing, which is surrounded by the plentiful creativity of his bandmates. He descends from his leader’s pedestal to level with the other four musicians, crafting intuitive, sensitive, and indeed ‘free’ jazz. The avant-garde hard bop played here is built on the tight relationships between Ron Carter, Tony Williams, and Herbie Hancock. Unrestricted, their astonishing exchanges redefine the role of their rhythm section, which becomes central to the sound signature of this remarkable group.

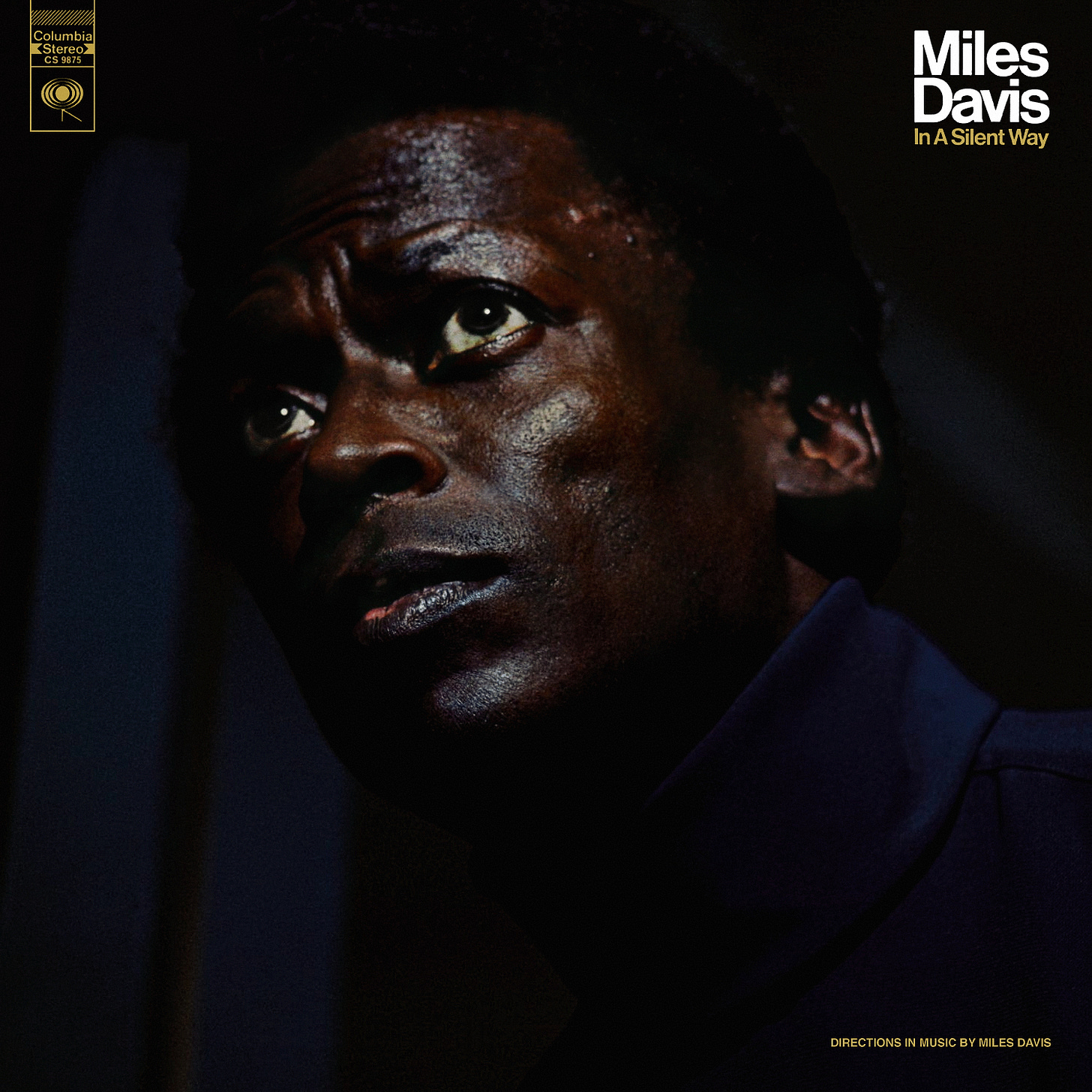

In a Silent Way

Regardless of whether it’s labeled as jazz fusion, jazz-rock, or electric jazz, In a Silent Way incited a quiet revolution. With this album, featuring two tracks of barely 20 minutes each, Miles Davis subtly shifted jazz towards rock, diverging from his previous avant-garde pursuits. The common thread in this unique musical adventure is John McLaughlin’s electric guitar, harmonizing with the keyboards of Joe Zawinul, Herbie Hancock, and Chick Corea to create an intimate, unorthodox encounter.

McLaughlin, though perplexed, delivered fascinating phrases. His groove, tinged with psychedelic hues, provided the perfect backdrop for Miles to express intermittent phrases with his famed precision. In a Silent Way lives up to its name, with the spaces and silences giving the music its distinct character. Miles was aided in his quest for perfection by producer Teo Macero, who painstakingly reviewed the recording session tapes to assemble this unique collage, the influence of which still lingers today.

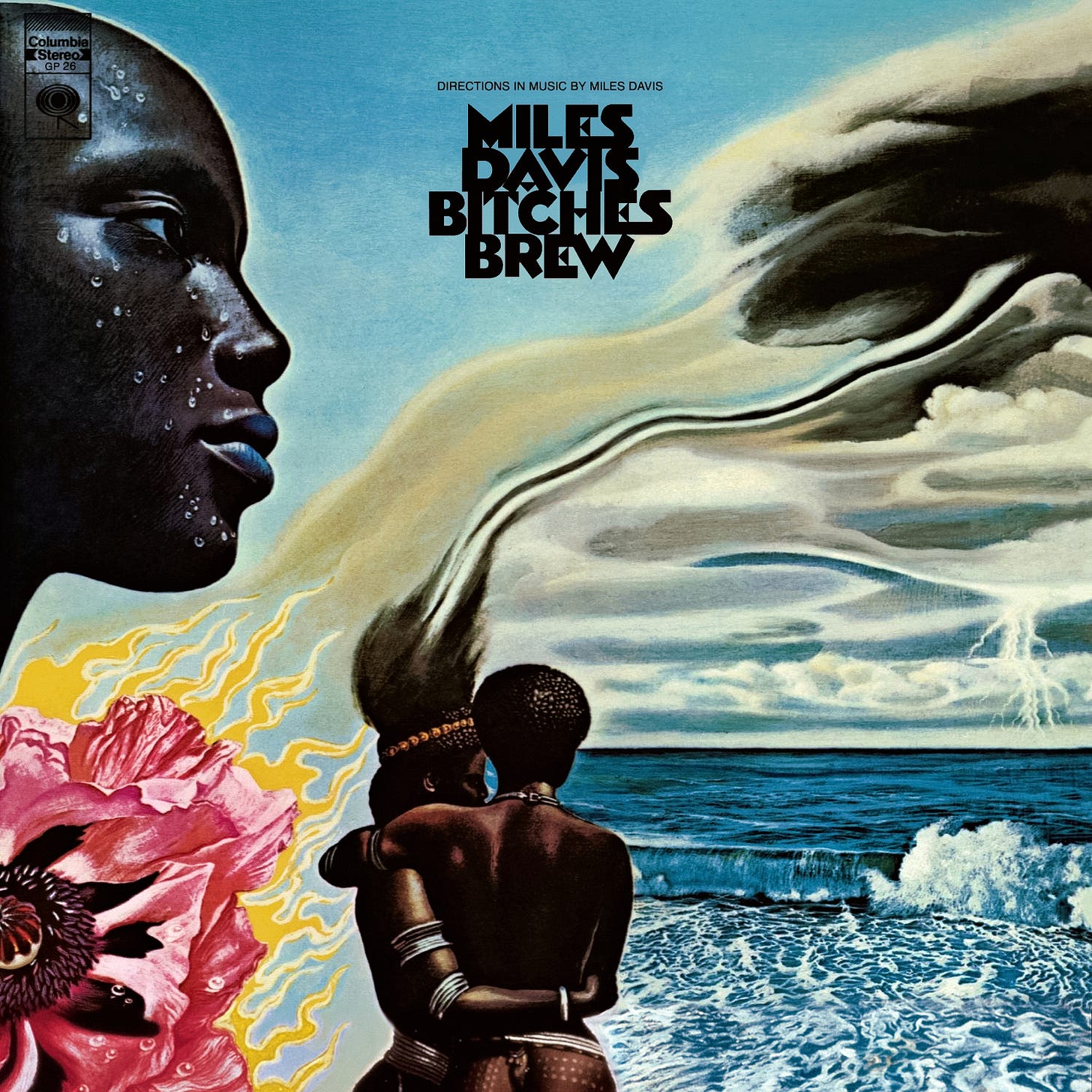

Bitches Brew

The rhythmic foundation laid by In a Silent Way marked the beginning of a transformation, but the summer of 1969 brought about a significant turn. Miles Davis secluded himself with twelve musicians to create the iconic double album Bitches Brew, released in April 1970. The fusion of jazz, R&B, funk, and rock’n’roll was a phenomenon never experienced before. It was like a 90-minute magic show where the trumpeter showcased his comprehension of Hendrix, funk, rock, blues, and jazz. This broad-mindedness was not entirely appreciated by the younger segment of his followers, who were unprepared for the complexity of his electric dialogue.

On the other hand, Purists believed that Miles had compromised his authenticity, and some even accused him of succumbing to commercialism. However, these views were unfounded. This avant-garde music was far from the mainstream offerings of American radio stations and was a challenge for the adventurous listener. Once again, Miles and his collaborators spent extensive hours in the studio, improvising around simple motifs and chord progressions without premeditated arrangements. Despite granting his sidemen complete freedom, Miles can occasionally be heard in the background, guiding the record. His playing style here is notably more sharp and aggressive than usual.

The six themes of Bitches Brew feature Joe Zawinul, John McLaughlin, Larry Young, Lenny White, Don Alias, Juma Santos, and Bennie Maupin, alongside his trusted collaborators Wayne Shorter on saxophone, Dave Holland on bass, Chick Corea on electric piano, and Jack DeJohnette on drums. The album is also distinguished by its post-production: loops, effects, echo chambers, and dozens of collages were used. Miles and his producer, Teo Macero, invested countless hours crafting this electric extravaganza. “Pharoah’s Dance” blended 19 elements: a pianist and a drummer on the right channel and another on the left, among others. Bitches Brew is about pushing boundaries—a stark departure from the traditional jazz jam session captured in a single take. The outcome is mystical and undefined: it’s neither pure rock, funk, or purely jazz. It’s an entirely new category.

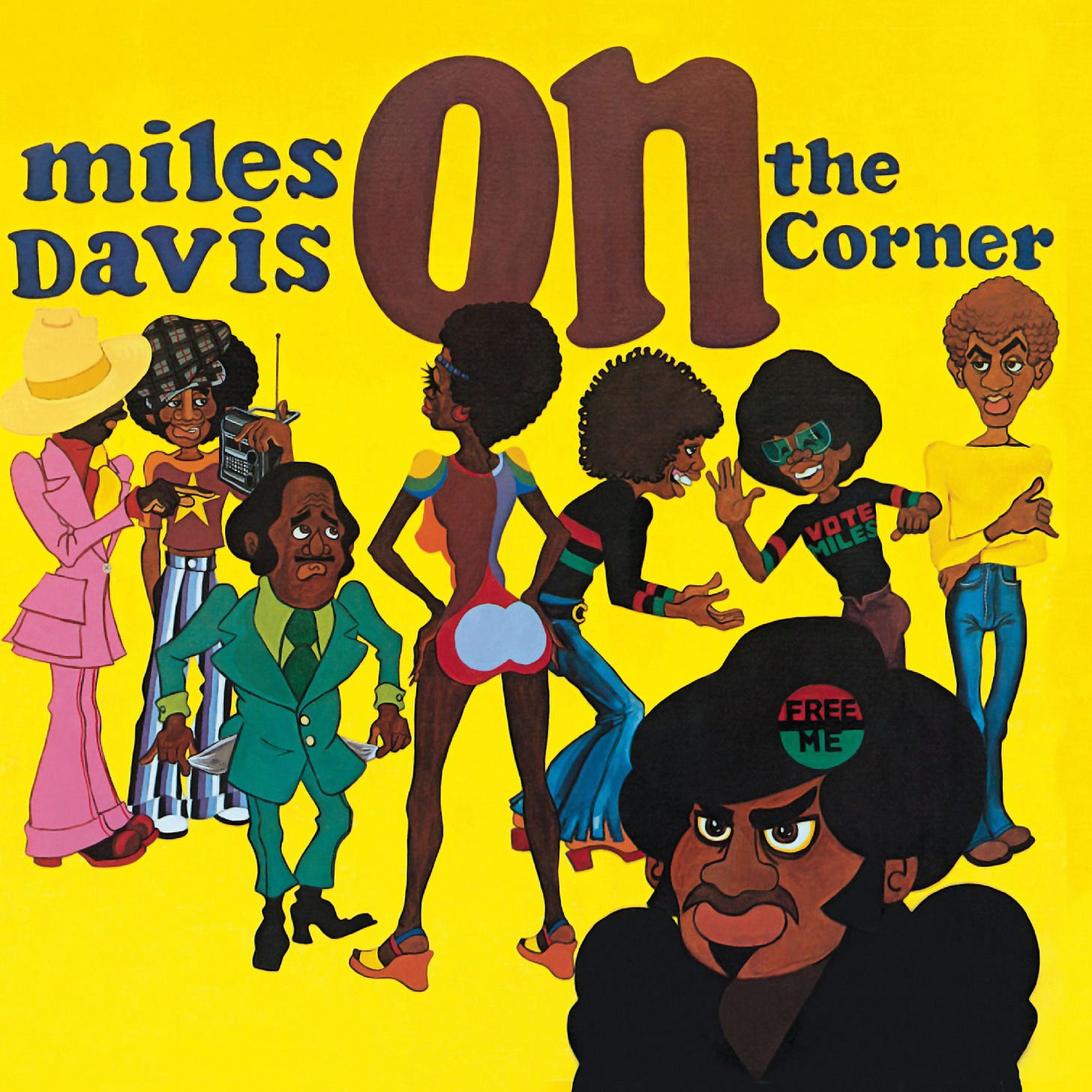

On the Corner

On the Corner is the Miles Davis album that resonates most with the principles of funk, not only due to the groovy cover art by cartoonist Corky McCoy. The trumpeter was in the studio with over fifteen musicians for the first time. The robust lineup reflects the buzz around this genre of music, recorded in New York in the summer of 1972. At the heart of it is the hypnotic bass of Michael Henderson, a former Motown workhorse. Surrounding him are layers of sound, introduced by a version of Miles we rarely hear: blistering white noise, exotic flavored percussion, marathon funk drumming.

It is a complete dismantling of the rules of composition, with harmony and melody taking a back seat. This record is a veritable treasure trove of unique sounds, like the famed filtered wah-wah effect when Henderson plugs his bass into a Mu-Tron pedal on “One and One.” In his autobiography, Miles mentions that in addition to being influenced by James Brown and Sly Stone (introduced to him by his then-wife, the funk artist Betty Davis), he was equally impacted by Ornette Coleman and, notably, the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, from whom he claims to have learned the method of addition and deletion in musical creation. This technique was crucial in Davis’ art, both in front of the microphones and behind the console. A commercial and critical disappointment, On the Corner and its hypnotic, repetitive motifs unfortunately found little success upon its release in October 1972.

Tutu

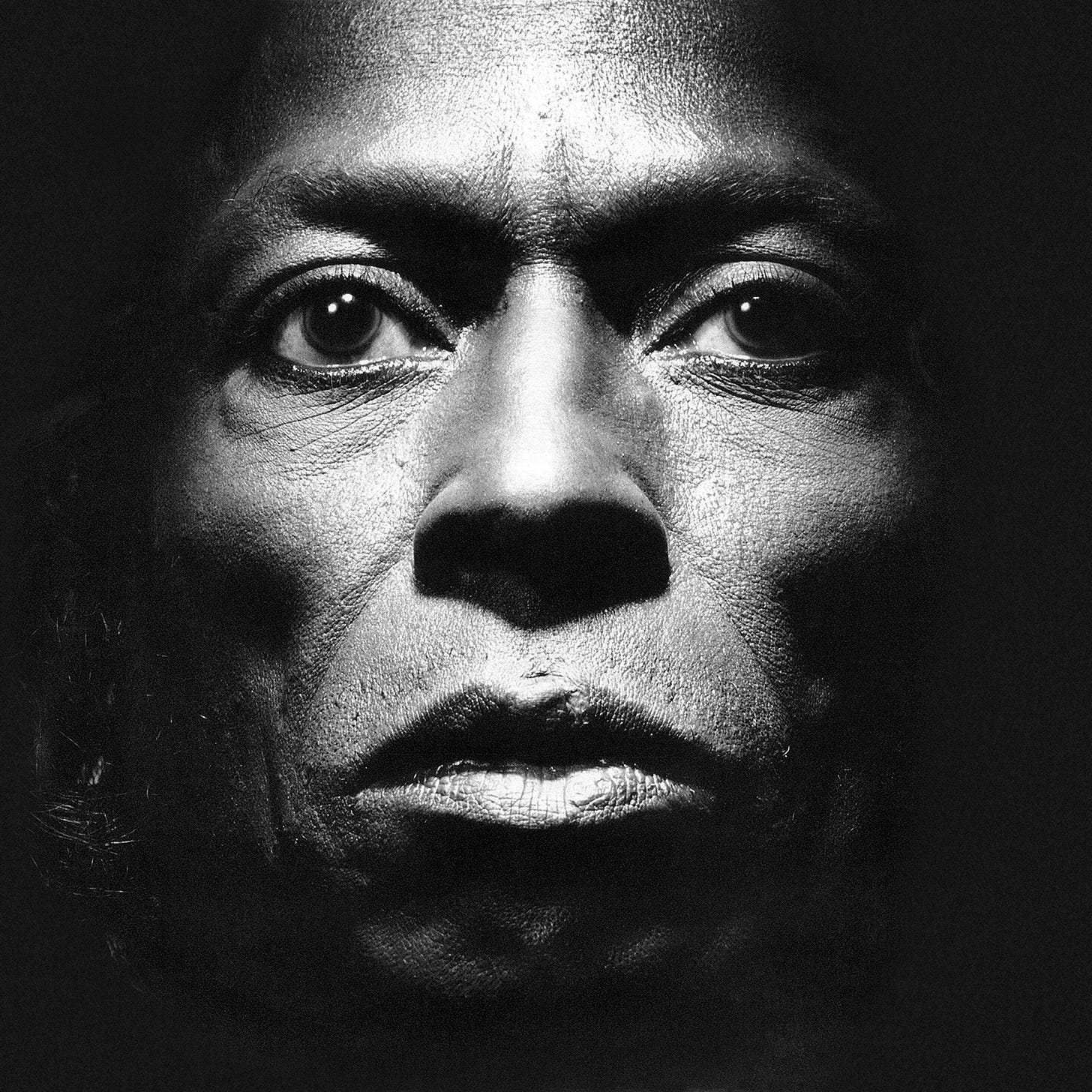

The later stage of Miles Davis’ career may not have been the most productive or artistically breathtaking, but it coincided with his popularity’s peak. At this point, he had nothing left to prove. This revered trumpeter had become untouchable and would play at sold-out venues worldwide. From his comeback with The Man With the Horn in 1981 to his passing on September 28, 1991, at 65, his electrifying recordings always aimed to reflect the times and highlight younger musicians. With its stunning cover (a black and white portrait by photographer Irving Penn), the funky Tutu is one of the highlights of his final decade. In 1986, Miles left Columbia—his base for most of his career—to join Warner. This transition marked another musical evolution: another fusion of jazz and funk.

The result was Tutu, an album distinguished by Davis’ collaboration with another musician, Marcus Miller. This electric bassist, a worthy successor to Jaco Pastorius and Larry Graham, designed a modern musical backdrop to thrust Miles back into the spotlight. Naturally sporting a very 80s sound, the synthesizer made a strong comeback. In addition to these two men, Tutu brought together veterans and longtime session musicians who were always eager to contribute to a Miles Davis project, namely George Duke, Omar Hakim, Bernard Wright, Michał Urbaniak, Jason Miles, Paulinho da Costa, Adam Holzman, Steve Reid, and Billy Hart. Tutu was the perfect soundtrack for the mid-80s when synthesizers dominated and oversized suits were the fashion.