A Letter to the People Who Feel Entitled to Comment

A public letter is a way to speak to people who won’t listen unless you announce yourself. The world loves to call its policing “help,” especially with women’s bodies.

Airplane armrests bruise. Roxane Gay, in Hunger: A Memoir of (My) Body, chronicles spending five-hour flights tucked against the window, her arm pressed into the seat belt, trying to create what she calls “absence where there is excessive presence.” That sentence contains an entire economy. The body that exceeds the seat dimensions must compress, apologize, negotiate for the right to exist in transit. The armrest itself becomes a kind of policy, determining who gets to travel comfortably and who must fold inward to avoid touching a stranger’s elbow. Gay’s memoir logs hundreds of these calculations. Where to stand in a hallway. How quickly should you walk when someone is behind you? Whether the chair in a waiting room will hold, and if it doesn’t, what the sound of plastic cracking will announce to every person in that room.

Gay opens Hunger by refusing the redemption arc her readers might expect. “The story of my body is not a story of triumph,” she writes in the first pages. “This is not a weight-loss memoir. There will be no picture of a thin version of me, my slender body emblazoned across this book’s cover, with me standing in one leg of my former, fatter self’s jeans.” She insists, instead, on the phrase “true story.” That distinction matters. A triumph narrative requires before-and-after photographs, motivational language, a closing scene where the protagonist has conquered her appetites and become acceptable to society. A true story makes no such promises. Gay explicitly states she is not offering motivation, has no “powerful insight” into overcoming an unruly body. She has written a book that denies its readers the satisfaction of watching her succeed at becoming smaller.

The Cleveland Clinic scene in Section 3 pins this refusal to something concrete: 577 pounds. Gay was in her late twenties. She sat in a meeting room with seven other people, an orientation session for gastric bypass surgery. For $270, she listened to doctors describe “the only effective therapy for obesity.” The psychiatrist told them that “normal people” in their lives might try to sabotage their weight loss. The doctors described hair thinning, nutrient deprivation, dumping syndrome. The cost of the surgery: $25,000. The doctor who examined her glanced at her chart, flipped through the pages, and said, “You’re a perfect candidate for the surgery. We’ll get you booked right away.” Then he was gone. Gay writes that she was “a body, one requiring repair.” That phrasing sticks. A body requiring repair, as if the fat can be addressed like a broken transmission.

What Gay provides instead of repair is inventory. Chairs that might not hold. Armrests that dig into thighs. Airplane seats with belt extenders. Medical spaces where doctors see the weight before they hear the complaint. Clothing stores that do not stock her size. Stages where podiums are too narrow. Bathroom stalls where the door barely closes. Restaurants where the booth won’t fit. Each space teaches a person to calculate in advance, to scout the room, to carry shame for requiring accommodation. The fat body pays constantly, in planning, in discomfort, in public performance of apology.

The public sees this performance and calls it concern. In Section 31, Gay addresses the constant commentary: “Your body is constantly and prominently on display. People project assumed narratives onto your body and are not at all interested in the truth of your body.” Fat, like skin color, cannot be hidden. Strangers offer statistics. Family members frame their worry as health advice. Gay writes that this commentary “is often couched as concern, as people only having your best interests at heart. They forget that you are a person.” The concern is itself a policing. It positions the fat body as a problem to be solved.

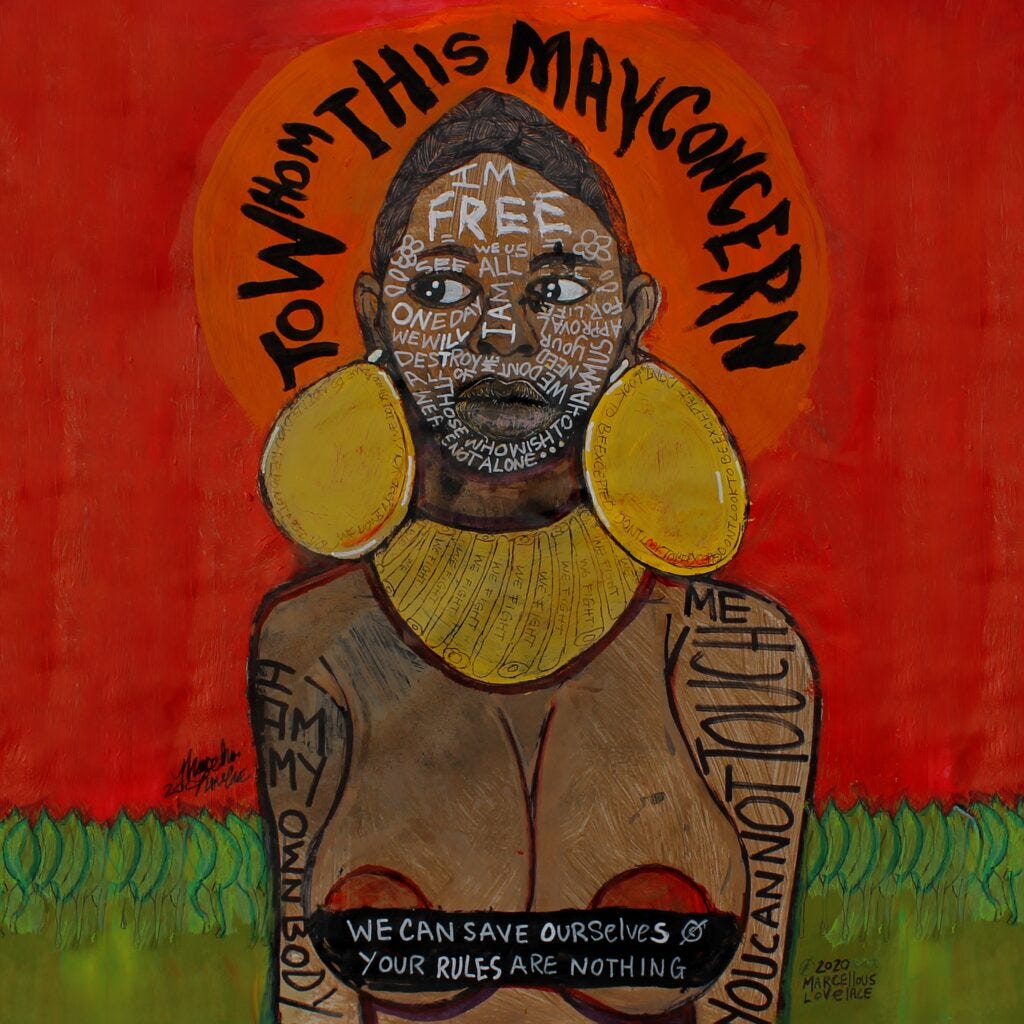

All roads lead to Jill Scott’s long hoped-for sixth studio album, To Whom This May Concern, dropping on Valentine’s Day weekend (February 13)—her first album in a decade. The title is the opening line of a letter you send to people who don’t deserve to be addressed by name. Scott announced the project on the second day of January, unexpectedly, when we needed it the most, releasing the lead single “Beautiful People” alongside cover art featuring a photograph of her mother, Joyce Alice. The album features collaborations with Ab-Soul, JID, Tierra Whack, and Too $hort, with production from DJ Premier and Om’Mas Keith.

“To Whom This May Concern” is the opening line of a letter you send when you don’t know the recipient’s name but you know they exist. It is the formal preamble to a complaint, a notice to a debtor, a warning to an institution. Scott’s choice of this phrase as an album title suggests she is speaking to people who do not deserve the intimacy of their names. According to press materials, the album “leans heavily into the power of connectivity, humanity, and collective home.” Paired with a title that sounds like a cease-and-desist letter, that language reads different.

“Beautiful People” names the people Scott loves. “My beautiful people, I just want to be cool with you/I am genuine, I love your soul, I do.” The chorus calls out directly: “Our love is bigger than time or race/Our love is rhythm and charm.” Beauty here is not a physical description. It is a category of belonging. It names who deserves softness, who gets claimed, who is invited into the space the singer creates with her voice.

What does it mean to call people beautiful in a culture that profits from making them apologize for existing? Gay writes in Section 40 about what she denies herself. “I deny myself the right to space when I am in public, trying to fold in on myself, to make my body invisible even though it is, in fact, grandly visible.” She denies herself bright colors. She denies herself “certain trappings of femininity as if I do not have the right to such expression when my body does not follow society’s dictates.” She denies herself “gentler kinds of affection—to touch or be kindly touched—as if that is a pleasure a body like mine does not deserve.” Each denial is a tax paid to the world’s expectation that she should be smaller, quieter, less present.

The comment section is everywhere now. The family member who suggests a diet. The doctor who sees the weight before the symptom. The stranger on the airplane who sighs when she sits down. Gay writes that her father has offered her weight-loss programs, books, brochures. “He has so much hope for what I could be if only I could overcome my body.” That hope is also a verdict. It presumes the body as obstacle, the self as trapped inside.

“Before/after” is how the world wants the story told. Gay refuses. In Section 5, she writes: “What you need to know is that my life is split in two, cleaved not so neatly. There is the before and the after. Before I gained weight. After I gained weight. Before I was raped. After I was raped.” The weight is tied to the violence. The body she built was protection. “I needed to feel like a fortress, impermeable,” she writes in Section 6. “I did not want anything or anyone to touch me.” The body became armor. The fat was deliberate. This is not the narrative weight-loss memoirs allow. This is not a triumphant return to discipline. This is a woman who made her body into a boundary because the world taught her that boundaries were something other people got to violate.

Scott’s album arrives nearly eleven years after Woman. She has been collaborating, touring, and visible without releasing her own work. In a December interview, she said, “It’s a lot of living in this album. It’s a lot of revelation.” Living is not triumph. Living is what you do when you are still here, still refusing to perform your damage for strangers.

Gay writes near the end of Hunger about a painted fingernail. Her best friend painted her thumbnail a lovely shade of pink. Gay stared at it on the airplane home. She could not remember the last time she had allowed herself that simple pleasure. Then she became self-conscious and tucked her thumb against her palm, “as if I should hide my thumb, as if I had no right to feel pretty, to feel good about myself, to acknowledge myself as a woman when I am clearly not following the rules for being a woman—to be small, to take up less space.” The thumb. The nail. The pink. That is what the world takes from women who exceed its dimensions, as the right to feel pretty, the permission to have a painted nail visible.

Before she got on that plane, Gay’s friend offered her a bag of potato chips for the flight. Gay refused. “People like me don’t get to eat food like that in public,” she said—one of the truest sentences in the book.

Scott’s “Beautiful People” plays while I write this. The vocal runs near the song’s end confirm what her fans already knew. She still sounds like herself. The voice has not been reduced. The album title addresses the world, not the beloved. To Whom This May Concern names the people who think they get to comment, diagnose, correct, and help. It names them without naming them. It puts them on notice. And then, track by track, it speaks instead to the beautiful people, the ones who deserve to be called by name.

This framing also made me think of the parallels with what D’Angelo went through after the Untitled video. I think the question of how people reclaim themselves physically in a world assuming ownership at a million touch points is really hard.