Album Review: All the Flowers Have Bloomed by Kofi Stone

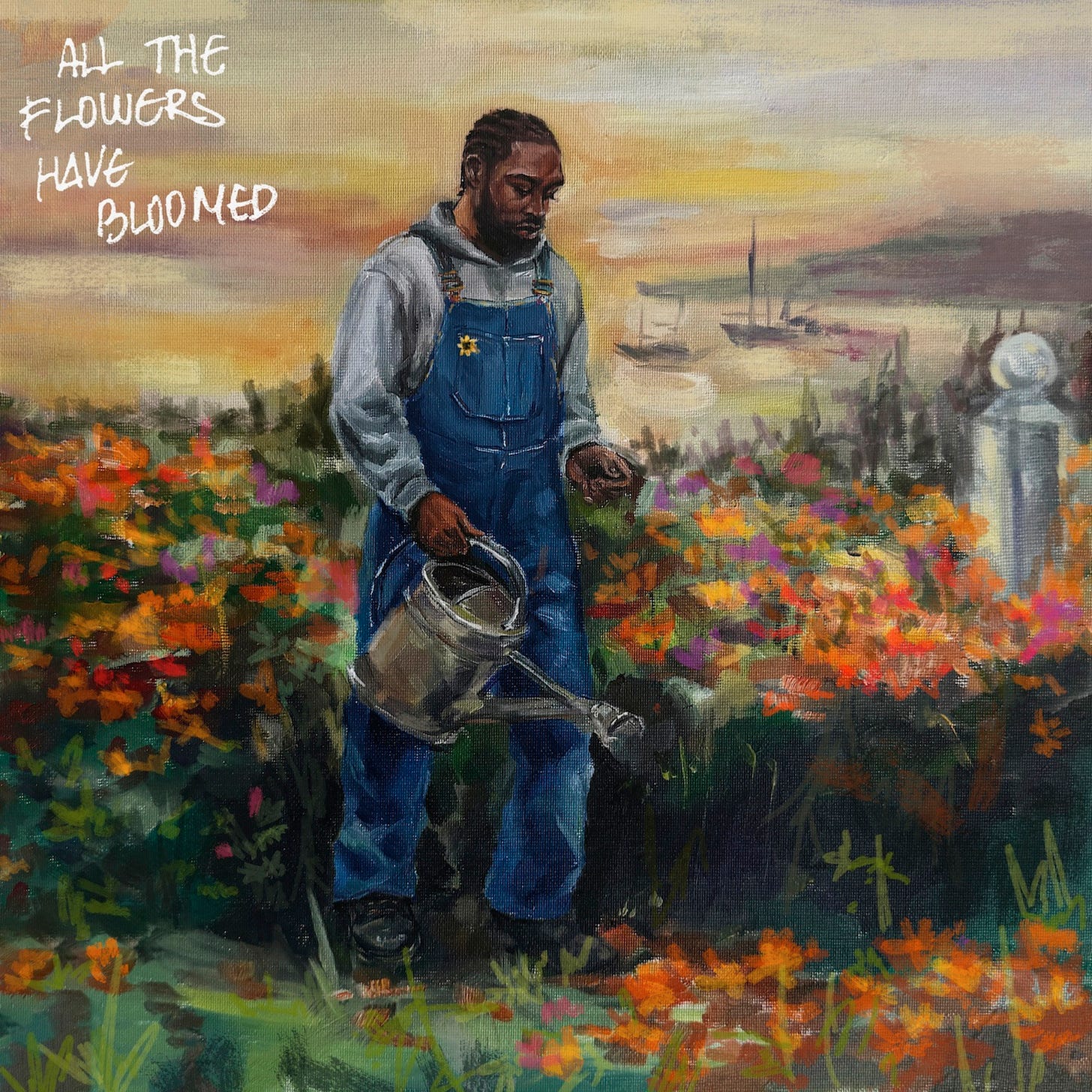

From Birmingham’s backstreets to hard-won peace, Kofi Stone keeps his storytelling close to the soil. All the Flowers Have Bloomed refines what’s already there, proving he’s still pruning what’s real.

With his third studio album, Kofi Stone doesn’t reinvent himself so much as deepen his roots. Raised in Birmingham’s working‑class Selly Oak after a family move from Walthamstow, the rapper spent his adolescence bouncing between after‑school studios and the soundscapes of Nas, Nat King Cole, and the Grand Theft Auto radio. Those experiences turned into a narrative‑driven style nurtured by a poet grandfather and a father who played blues and hip‑hop on long drives. His last record, A Man After God’s Own Heart, was an ode to faith, family, and self‑examination, and it confirmed him as one of the rare UK rappers who balance humility with mastery. All the Flowers Have Bloomed represents the next stage in that arc, not a stylistic pivot but a return to the soil that formed him, pulling new colours out of struggle, spirituality, and kinship. It closes a trilogy that began with Nobody Cares Till Everybody Does and continued with A Man After God’s Own Heart while marking an artistic maturation as a walk through victory, hustle, love, joy, and peace.

Growing up outside of London gave Stone what he calls the underdog spirit. Limited resources and infrastructure in Birmingham meant he had to carve his own lane, and that determination bleeds into the album’s opening track, “Seeds.” Over a mellow, atmospheric beat, he recounts his family’s move from Walthamstow to “Brum town” and parties at his mum’s house while labels tried to dumb down his ambitions. The hook pivots from hardship to gratitude: Air Forces soaked in rain, face forward, praise God for pain answered by assurance. He even mentions a neighbor housing his family after a house fire, framing the community as fertile ground. That theme of planting and watering recurs throughout the record; Stone told Hunger Magazine that his affinity for flowers isn’t decorative but a philosophy—“You plant seeds and you water them and good things come.”

On “Pansy,” Stone urges to “live a little” and “spread love, stay strong.” He apologizes for neglecting his loved ones while chasing rhymes and dedicates his verses to his father, hoping his father hears them when the record drops. The song balances regret and gratitude; he thanks God for grace while acknowledging that evil circles like vultures. When he repeats the call to “live long” over a smooth, soulful beat, it feels like Stone is reminding himself as much as us. “Boats” picks up the motif of distance and return. He opens, sitting at his mother’s desktop in 2005, trying to make the best of life and marvelling that the police didn’t arrest them. A trip to Venice becomes a metaphor for escape, but he quickly dives back into the realities of depression and therapy, admitting he once believed he could “keep it humble even though they didn’t rate” him. As he sings that delay isn’t denial and prays for brighter days, the pastoral calm he projects feels earned rather than forced.

While many rappers would follow such heaviness with bravado, Stone uses “Flowers Flow” to reframe his confidence. He remembers rapping with “a handful of rage” and being home from school in time for Home and Away. He climbed over industry gates when doors were closed, honing his craft until he could step on stage and light up the room. “Badder than who? You ain’t badder than me” might read as boastful on paper, yet within this album, it feels like a self‑pep talk. The outro returns to the garden metaphor: “Just give me my flowers/10,000 hours/When life gets deep, gotta find my feet.” He isn’t seeking empty accolades but recognition of a decade of grind.

The album’s centerpiece is “Thorns,” a devastating six‑minute narrative that features vocalist Jacob Banks. Stone begins by chastising someone for missing dinner and confesses to drinking alone while using new vices to numb old wounds. As the verses go on, he details the cycle of mental illness, medication, and the weight of parenting amid his mother’s psychological struggles. He prays for relief and wonders if God is teaching him a lesson, a question left unanswered as he contemplates suicide and acknowledges the voices urging him to hang himself. Banks’s hook, “This pain won’t pay the bills/No more love to give/I’ll fly if I fall,” offers no resolution but adds an ethereal contrast to the raw verses. He directs empathy outward, apologizing to a woman abandoned by her partner and praying that evil will be her teacher. In doing so, he brings clarity to the album’s wider conversation.

“Rainfall” is the narrative pivot. Stone retraces a near‑miss with violent death and a later mental breakdown, confessing that he once measured his worth by money while his family looked at him like a paycheck. He interlaces his pain with accountability—“A man really only has his word and his father’s name” and “What you sow is what you reap.” And then, “Just know when you plant the seeds, don’t forget the rain” ties trauma back to growth, reminding those who nurture that it includes sunlight and storms. It’s a confessional moment that doesn’t glamorize close calls or mental health struggles, but instead, uses them as compost for wisdom. A sense of weariness hangs over “Water,” where Stone dreams of a day without worry and confesses that he’s running out of hope. The hook borrows from the spiritual “Wade in the Water,” but his tone is more resigned than redemptive: he feels a weight pushing him down, drowning in a sea of obligations. The second verse shows him straining to look at life through a new lens, acknowledging he’s getting older and can’t keep chasing pennies.

What has changed most since A Man After God’s Own Heart is Stone’s steadiness. That record wore its vulnerability on its sleeve, but it sometimes felt caught between testimonial and sermon. He seems more comfortable letting paradox stand, where he can speak of faith without trying to convert, and he can admit to suicidal thoughts without framing recovery as triumphalist. The songs revolve around common images (seeds, rain, flowers), yet he varies them enough to avoid monotony. There’s a pastoral calm to the pacing, and you can hear Stone’s sense of purpose sharpen as he meditates on family, poverty, and legacy. When he raps, “What’s a man without supply? A wrong without a right,” it resonates as a man reckoning with his responsibilities.

The title track is the dawn that brings full circle. “All the Flowers Have Bloomed” opens with Stone addressing a crowd: “Everybody in the house, how you doing tonight?” It’s the only overtly celebratory moment on the record, complete with two‑step instructions and toasts at the bar. “All the flowers have bloomed, just like it’s the middle of June,” acknowledges the album’s thesis, letting the blooms unfurl. The second verse fuses praise and self‑affirmation, referencing returning to church and promising to be the change we hope to see. Where early songs grapple with identity and scarcity, the closer radiates contentment. It’s not that everything is solved. It may not attract new fans looking for club anthems or instant bangers, yet those who have followed him since day one will recognize a craftsman who has slowed his flow without dulling his edge. Stone simply pinpoints that he’s part of a larger ecology, and for once, the conditions are right for the garden to flourish.

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Seeds,” “Pansy,” “Thorns”