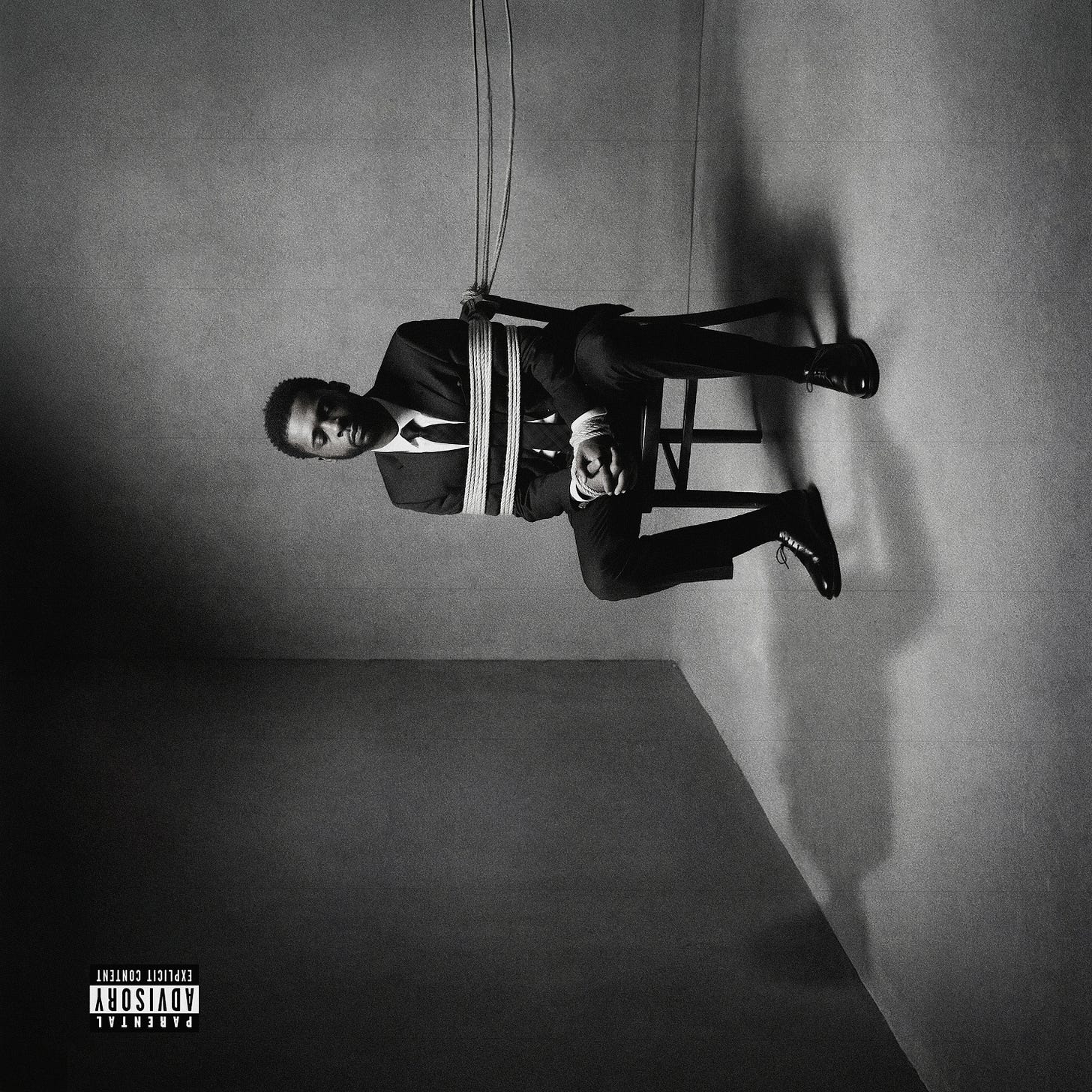

Album Review: ARD by KUR

The Philadelphia rapper’s latest project cycles through depression, apology, and designer spending with an honesty that outpaces his editing. The best songs name specific wounds.

Seasonal depression gets announced inside the first thirty seconds of this record, raw and unscripted, just a voice memo where somebody watches traffic on the expressway and imagines every driver in every car fighting a battle nobody knows about. The intro to “Hard to Accept” could pass for a therapy session uploaded by accident, and that sloppiness is part of why it works. Somewhere in the middle of all this sits KUR, a talented rapper who has been grinding for over a decade in Philadelphia’s independent lane, and his decision to open an album saying “that shit seasonal depression shit be real though” plants a flag that the next thirteen songs will struggle to honor. Once the verse kicks in, the vulnerability burns off quick.

ARD dropped in the thick of a cold stretch where KUR had money but no peace. The title borrows from Philly shorthand, that flat “ard” people toss out when they’re done arguing or done listening, and the whole record lives inside that exhalation. Dude can afford Hermès pillows but still wakes up with his ribs showing from stress. That contradiction is the album.

Most rappers apologize to one person per song. KUR runs through his whole phone book on “My Fault Yo!” and doesn’t let himself off the hook for any of it. He names his block, his father, his brother, his cousin, his grandmother. The grandmother bar is the one that stays with you because she died before he could keep his word about looking after the family, and he delivers it flat, no theatrical pause, just information that still burns. Then the second verse peels the guard back completely. He confesses that some nights are corny-lonely, that he wants to call someone but feels like he’d be forcing the conversation, and that “it turn out bad when you keep it all in.” For a record packed with luxury name-drops and club anecdotes, these stretches feel smuggled in, as if KUR has to trick himself past the bragging to reach the thing he actually needed to say.

Nobody on this album fumbles harder than the version of KUR who shows up on “Winston.” The phrase “most times” opens almost every bar, and instead of building toward growth, that repetition drills down into habit. He’s always with somebody new, always ducking a good situation because he’s embarrassed to sit at a restaurant with one woman, always aware of the pattern and doing nothing about it. That detail—ashamed to be seen in public one-on-one—is a strange, precise admission that no ghostwriter would invent. A few bars later he pivots to counting money and racking up Hermès purchases, and the pivot itself tells you he can only sit in that vulnerable place for a handful of lines before the spending reflex rescues him.

The camera metaphor on “Keep Rolling” earns its weight because the confessions sit right next to the posturing. The camera catches him dining with women and blowing money without flinching, but it also records the instant his card declines and the night he cries thinking about his father. The line about people only loving you when you’re hot and losing friends right before you reach the top hits without melodrama because it arrives next to frivolous ones about trucks and bottle service. “Tell Me You Proud” goes deeper into the family wound. He hid drugs in his mother’s vents and couch cushions, and he says it plainly, then asks the people around him to say they’re proud of him anyway. The gap between what he’s done and what he needs to hear from his family sits right on the surface, and KUR refuses to sand it down with a redemption promise.

Memory and geography collide on “Summer in V.A,” where KUR rewires the record’s coordinates. He recalls being sixteen in Virginia, getting his hair braided by a woman named Linda he hasn’t spoken to in years, and the fallout from some disagreement he doesn’t fully explain. The details are small and unglamorous, which is why they stick. Seven different women taken to a movie theater, a self-lecture about not depending on anyone, the admission that he “ain’t see you in a while, what’s the word?” is the only thing people say when he goes home. “Couldn’t Rest” follows that same frequency, piling up names and debts. Greg in a coffin. His mother reminding him he makes time for everything except her. A friend named T promising plays outside of rap. An hour after his graduation, he had to pack up and head to the trap, no celebration in between. The accumulation of these scenes doesn’t feel like a list because each one drags a separate kind of burden behind it.

G Herbo’s arrival on “Humbug” jolts the album out of its own head. KUR’s verse is already wound tight with grief over a friend named Alex, guilt about past drug use, depression that shrank him physically until his ribs were visible, and the loyalty math of fifty-nine boys for life regardless of right or wrong. Herbo comes in and flips the energy loud and blunt—grabbing a ski mask, dropping twenty thousand on a single outfit, daring imitators to match his life. The two don’t harmonize neatly, and that friction gives the song a different pulse from the rest of the album. Herbo’s aggression throws KUR’s self-interrogation into sharper relief. The hook about fixing your brother’s problems and not wanting anyone to die in the hood hits heavier bracketed by both perspectives.

The roughest material arrives at the end. “Reminding Myself” closes the record with a lost child, a hospital drive in denial, tears that came while his smile wouldn’t. He wanted his granny to tell him she was proud, and now she’s gone and the chance went with her. Then he drops to his knees, prays, and concedes he’s been straying from whatever mission he set for himself. The outro turns into a plea for help getting where he’s going, repeated over and over, which could have felt redundant but instead resembles a man who doesn’t know how else to end the conversation. His final spoken words are about the hardest lesson being to shut up and just say “alright,” and even that, he says, makes people mad. The album stops there, unfinished.

Where ARD loses steam is in the middle, where joints like “10 Cent Movie” and “Liked It Betta” recycle relationship gripes without the specificity that makes “Hard to Accept” or “Reminding Myself” burn. The sex talk on “Winston” has a self-aware edge that keeps it interesting, but “Jett 2 Holiday” and “My Love, My Love” blur together into shopping and women with less to chew on. KUR’s ear for beats stays consistent, and the production carries a low, humid pressure throughout, but three or four songs coast on charisma where the writing thins out. When he locks in on grief, family debt, and the distance between what he can afford and what he can fix, the record punches well above its commercial lane. The club autopilot loosens the emotional thread, and you feel the runtime.

Solid (★★★½☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Hard to Accept,” “Tell Me You Proud,” “Reminding Myself”