Album Review: Ca$ino by Baby Keem

Nearly five years between albums is a peculiar bet for a rapper who won a Grammy at twenty-one. Ca$ino digs into that wager with family confessions and desert mythology.

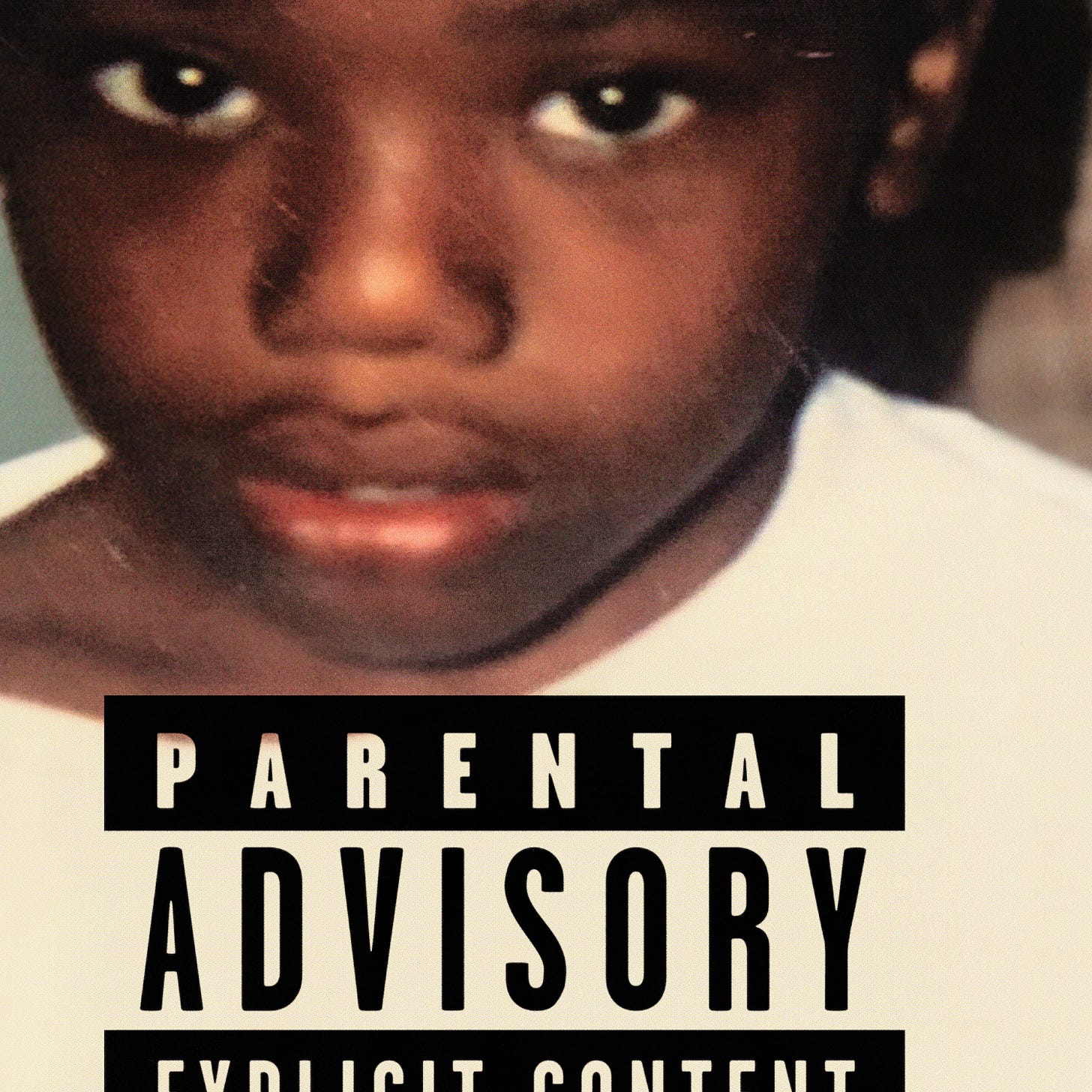

The cover of Ca$ino is a baby photo. Whoever chose it understood that this album spends more time looking backward than forward, that the name on the marquee belongs to someone who grew up watching adults gamble with his stability long before he could gamble with anything himself. Nearly five years have passed since The Melodic Blue, a span that saw Baby Keem contribute production and verses to Kendrick Lamar’s Mr. Morale & the Big Steppers, win a Grammy for “Family Ties,” tour arenas, and then largely vanish from public view.

There were teases of a different project, one called Child With the Wolves, that never came to fruition. Ca$ino materializes instead, titled after both a place and a habit, carrying all the accumulated weight of a twenty-five-year-old rapper who spent his public silence apparently deciding how much of his childhood to put on record. The Kanye and André 3000 influence is there, and the old persona is present. The cocky yelps, the manic vocal shifts, the instinct to flex immediately after confessing something awful. But the lyrics now carry more family detail, more resentment about being watched, and more blunt self-reporting about what money did to his nerves. He still comes off as a kid who learned to be loud so people would stop ignoring him. He just has more to be loud about.

Before the album dropped, Keem released three short documentaries under the title Booman, his childhood nickname. The first installment opens on a one-year-old Hykeem Carter in a one-bedroom apartment in Long Beach, California, living with his Aunt Connie and his grandmother. Connie narrates the family’s early years, recalls witnessing violence in their own backyard, and Kendrick appears speaking plainly about Section 8, welfare, general relief, and what he calls a “warfare environment” they were all born into. The second installment widens more into the archives and recounts the decision to relocate to Las Vegas in search of cheaper rent and distance from what was breaking them. Two facts from those films reshape how the album’s family lyrics hit: Connie, not Keem’s mother, was the one who pulled him out of a group home at age six, and the grandmother who died in the house Keem bought for her was also the woman who raised him after his mother could not, and the third installment is where he is now.

On the two-part title track (carried by a banging Cardo beat), Keem announces he “barely had parents” and grew up casino, as though the noun were a condition rather than a location. He snaps that he’ll “yank them fuckin’ chains off” and names “no soldiers in this rap game,” ricocheting between taunts and admissions so quickly that the aggression registers as a nervous tic. “Circus Circus Freestyle” compounds this with twenty-five million as a sticker price and hating-ass listeners waiting on a slip-up. He jogs through old beefs, bad exes, and Kobe memories in the same cadence, never pausing long enough for any of it to bruise. “House Money” escalates into a full confrontation. He demands that a “pussy-nigga, get up and get out the house, get up and get off the couch,” then asks, “What does your workin’ amount?” The comedy arrives when he admits, two bars later, that he “found me a new carbon copy ‘cause you out here movin’ too sloppy.”

The confession songs answer differently. “No Security,” the opener, buries its sharpest lines in the middle of a verse that begins as standard post-fame complaint. Keem says, “Uncle Andre just passed, I can’t help but bear blame,” then wishes he’d “got him help when the resources came.” He turned twenty-two and was done with the Range, meaning both the vehicle and the patience for maintaining a public life. His mother looks at him just like “she goin’ to the bank.” His grandmother put him near “spots with the bank.” Then, abruptly, he recounts his “mama walked me ‘round with no shoes in the cold” while she “was sleepin’ in a tent,” and “goin’ back and forth to jail” becomes a question about “should I bail or can I vent?” The pivot is so fast it mimics how someone actually tells a hard story, rushing through the worst part before they lose the nerve. “Highway 95 Pt. 2” slows the rush. At thirteen, he slept in ditches, couldn’t recall his mother in the kitchen, got a zip of weed from friends he held it for but didn’t smoke, and sat outside hungry because the food stamps ran out before the month was over.

Keem names Las Vegas the way people name a scar. He identifies the city as the place that shaped him and the place that took people from him, and he rarely separates those two facts. “I Am Not a Lyricist” puts it bluntly. “They don’t call it Sin City for nothin’,” he writes, then catalogues what that means at street level. “Five hundred for an escort, and she does it all,” his uncle “saggin’ with his prostitute, words slurrin’ off that Absolut vodka,” his mother being “serv[ed]” drugs as though it were a favor. He watched all of this as a child and thought it was normal until he realized they were estranged from normalcy altogether. He “wish we never came to Vegas from Long Beach,” a line that collides with the documentary footage of Connie describing the move as a bid for survival. A casino is where the house always wins, and Keem grew up inside one where the house was his family, and the losses were not financial. He’s comparing himself to a machine designed to take your money and give you nothing back by saying he’s “that slot machine that nobody held,” and telling you that nobody held him, either.

Kendrick Lamar appears on “Good Flirts” and “House Money,” and his presence does different work on each. The “Savior (Interlude)” credit on Mr. Morale proved that Keem could hold a thesis when the subject was family and inheritance, and “Good Flirts” taps a gentler version of that instinct. Alongside Infinity Song’s Momo Boyd, Kendrick’s verse opens with a stuttered admission about never knowing a love like this, then folds into domestic life, watching Sinners on the couch, debating whether to decorate her walls or log off to Pinterest, confessing he’s been missing her body in a cadence so playful it registers as improvised. But also takes a slight jab at Young Thug, if you know, you know.

“Shit, I gossip with my bitch like I’m Young Thug too.”

On “House Money,” the contrast sharpens. Kendrick sings the hook like a man entering a room to pick a fight, all powered-up swagger and an I-smell-something ad-lib that tilts the track’s aggression from personal to theatrical, similar to G-Unit’s “I Smell Pussy.” The Hillbillies single from 2023 showed Keem and Kendrick could turn looseness into something sticky without losing craft; here, the two operate as mood regulators, one calming a room and the other torching it.

Keem spends his verses on the playful “Sex Appeal” cataloguing Miami encounters and endorphin rushes, sounding half-amazed and half-exhausted by the pace of his own nightlife. Then Too $hort enters with church girls sinning and an old-school directness about wanting the newest woman in the room, and the generational collision is jarring because the older man is plainly more comfortable with desire than Keem is. The uninspired, poppy “Dramatic Girl” brings Che Ecru into a softer register, the closest Ca$ino gets to a love song that isn’t also heavy or bass-heavy. The track asks for patience from a person who apparently needs to take off a mask first. Keem’s singing here is careful and thin, less about showing range than about sounding uncertain, and the song’s willingness to stay small gives the album a pocket of air it needed after a dose of heavy songs.

“No Blame” closes the album with James Blake’s additional vocals and Keem addressing his mother directly. He says he was seven years old, waiting in pajamas, and she promised to come home. His grandmother told him his mother had died, and he had to figure out how to live with that information while she was actually still alive. CPS showed up at the door while his mother and grandmother fought for custody of him. She smoked cigarettes in the house until it felt haunted. She was pregnant with a Xanax in her stomach. Every one of these lines is delivered without the vocal pyrotechnics Keem uses elsewhere, and the drums strip back to let his voice sit exposed against Blake’s glacial hums. The song ends with him running away on Mother’s Day, cold and unloved, still not blaming her.

The album’s problem is not contradiction—contradiction is fine, and frankly honest. The fun songs are competent and sometimes very funny; the family songs are some of the best writing in recent rap (specifically, mainstream rap) about what it means to become currency to the people who were supposed to protect you. Outside of the influences and impeccable production choices, Ca$ino is by far his most accomplished work as a solo artist who can not only deliver crowd-pleasers, but what Keem accomplishes on the personal side is strong enough to restructure how you hear everything around it.

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “I Am Not a Lyricist,” “Highway 95 Pt. 2,” “No Blame”

I Am Not a Lyricist is so good

I also really liked the title track. Great album