Album Review: Chasing by Ady Suleiman

After years away, Ady Suleiman returns with songs about bad love, late-learned self-respect, and trying again. He also tackles heartbreak, police violence, and family pride with his most honest work.

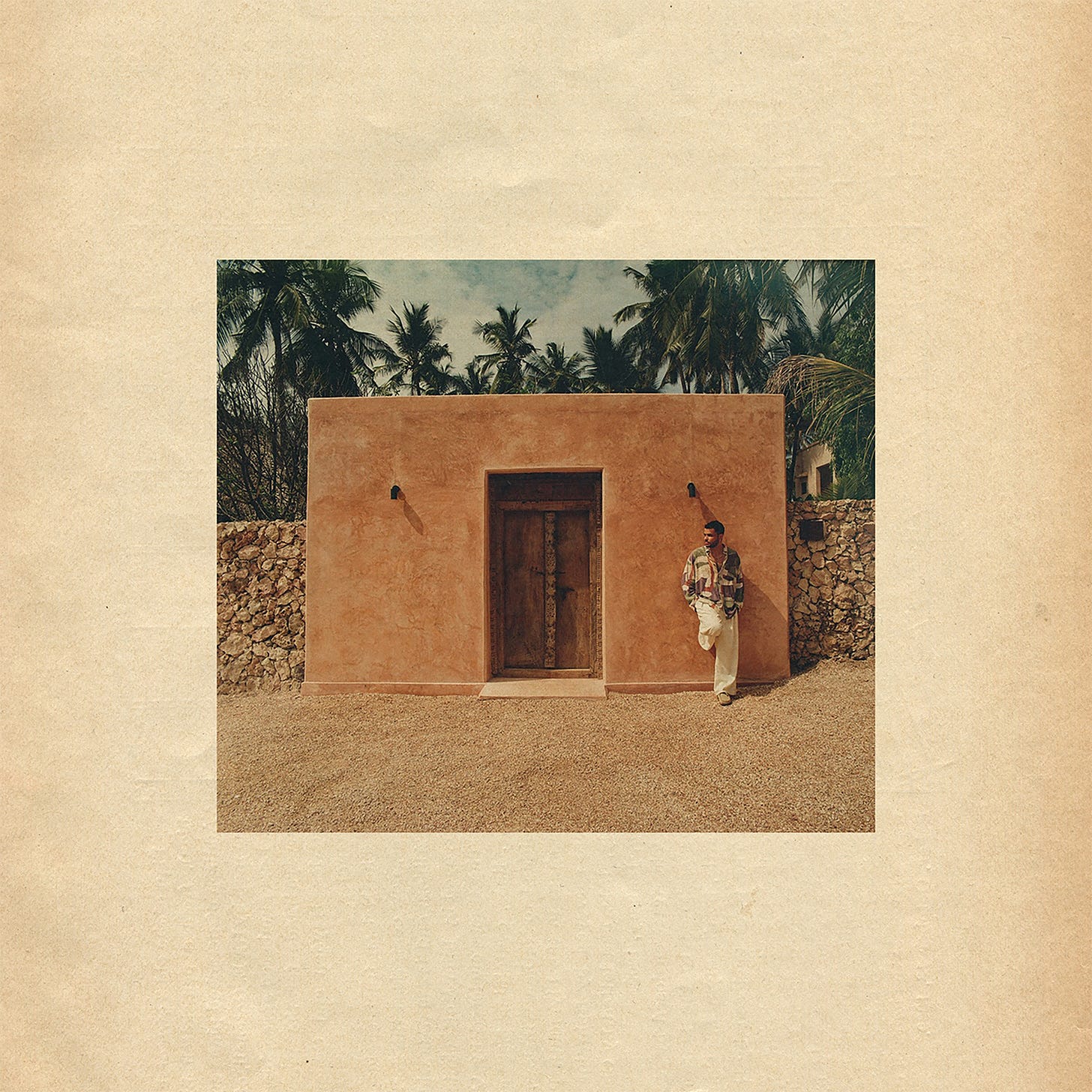

After his 2018 debut Memories, Ady Suleiman went quiet. Not the usual album-cycle quiet where an artist posts throwback studio pics and teases unreleased snippets. The real kind, where the industry moves on without you and you have to decide if music is still worth the stress it costs. Six years passed. A pandemic happened. Mental health got bad enough that making songs felt more equivalent to an obligation. Eventually, Suleiman left London for Zanzibar—his father’s home, a place where he could reconnect with family and remember what his voice sounded like when he wasn’t trying to please a label. The trip was supposed to last two weeks. He stayed three months. What came back with him is Chasing, recorded with producer Miles Clinton James, who refuses to separate heartbreak from police violence from family gratitude, because Suleiman knows they all live in the same body.

The album starts by admitting he wasted too much energy on the wrong person. Ran 900 miles for love that was never there, sang a thousand songs for someone who didn’t care, built a ladder from the bottom up just to realize she was never going to climb it. That’s the engine here when you’re earning too late that self-respect means walking away even when it feels like the only thing you know how to do is stay. On the title track, he redirects all that desperate affection inward, trying to love himself with the same intensity he gave to someone who left him alone in the water. It’s just the plain admission that you can waste years of your life chasing approval from people who will never give it.

Then the album complicates things by flipping the script. Suleiman spends the next few songs admitting he was the problem too. “Ain’t Your Song” is denial piled so high it collapses under its own weight—“I’m never lonely/I never cried/I mean to say that every time I said I love you that I lied”—and the more he insists he’s fine, the more obvious it becomes he’s lying to himself. He’s chronicling all the jealousy he claims not to miss, all the love he swears meant nothing, and you can hear him losing the argument in real time. It’s the kind of song that only works if the artist is willing to look pathetic, and Suleiman commits fully.

What makes Chasing feel more substantial than just another breakup album is that Suleiman refuses to let romance be the only crisis worth naming. Halfway through, the record cracks open to let in the weight of the world he’s been living in while trying to heal from bad relationships. “Brother,” inspired by the 1993 murder of Stephen Lawrence in Woolwich, where Suleiman was living when he wrote the song, doesn’t offer comfort or resolution. It just catalogs mothers losing sons to guns, police brutality that never stops, politicians spinning lies while the press demonizes the people getting killed. “How am I gonna show some love/They just wanna see me burn” doesn’t sound like a slogan you’d put on a T-shirt. It sounds like someone genuinely asking themselves if it’s worth trying to choose love when the world keeps burning your people down. Jah Digga’s spoken verse on “Call from Jah” tries to be a pep talk (stick your chest out, pull your socks up, pain is temporary), but the song can’t escape the feeling that some pain isn’t temporary at all, that it’s baked into the structure of how Black men move through the world.

The album’s messiest admissions come when Suleiman stops trying to be the good guy and just sits with how badly he fucked things up. “Trusted You” replays a relationship like a crime scene he can’t stop returning to: “I left you alone in the water/And I should have known how to love you better.” No excuses, no pivot to blame her for something she did. He made her insecure. Denied her cries. Took her for granted. Now he’s tortured by shadows of her that move through his mind but never stay long enough to feel real. Miles Clinton James’s production gives him space to sit in that guilt without rushing him through it, and the restraint makes the song land harder than if it tried to drown in strings and drama.

Where things get complicated is “Never Meant to Hurt You,” which brings in Kofi Stone to add a second voice to a situation Suleiman can’t seem to walk away from. He’s admitting he shouldn’t see her again while also admitting he misses “gripping on them thighs”—too blunt to be romantic, too honest to write off as posturing. He’s trying to rebrand a mistake as fate, calling it something cosmic when it’s obviously just him going back to someone his friends told him to leave alone. Kofi’s verse flips the temperature completely. He calls out all the games—acting like you don’t know each other, blocking numbers, making peace just to circle back again—and his “arms stretched, could we make the peace” that “might double back, would you wait for me” appears to be negotiation. That tension between what he wants and what he’s actually doing gives the song more weight than the production probably deserves.

There’s a stretch where the anxiety takes over completely. Chest pain at a party on “What If,” being back at your parents’ house and not recognizing who you are when you’re there. “What if I never find my feet under me” keeps repeating until it stops being a question and starts sounding like something closer to prayer. “Cry” tries to talk him through it—you’re gonna get better, you’re gonna fly—but the pep talk doesn’t land when you’ve been standing at a distance from yourself for too long. On “Trouble,” he’s counting months he didn’t notice slipping past. One plus two plus three, then six months more. He wasn’t looking for a lullaby, never wanted to be treated kind. That line cuts because it’s not posturing. It’s him admitting he avoided real affection because he knew he couldn’t handle it, and by the time he looked up, the tide had already carried him too far out.

The album ends on family. His older sister’s strength, his younger sister baking, his father as the man he hopes to become, his mother who he says defies words. Jambiani, rum and palm trees. The details keep “Family Tune” from drifting into generic gratitude. He wants to be a father like his father, and that wish carries weight because the whole album has been about figuring out what not to repeat. Chasing works best when it accepts that heartbreak and systemic violence and family pride aren’t separate categories. They’re all part of the same life, the same body trying to figure out how to keep going when everything feels like it’s burning down. Suleiman came back from six years away with something that doesn’t lie to you. That’s not nothing.

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Brother,” “Trusted You,” “Trouble”