Album Review: Don’t Be Dumb by A$AP Rocky

Eight years of noise, a courtroom cloud cleared, fatherhood that shows up in actual bars. A$AP Rocky came back with something to say and something to defend.

The better part of a decade passed as tabloid furniture. The delays, the leaks, and the relationship that put him in more fashion editorials than rap magazines. The felony assault case that dragged from a 2021 Hollywood altercation with former A$AP affiliate Terrell Ephron all the way to a not-guilty verdict in February 2025. By the time Don’t Be Dumb arrived, the question wasn’t whether A$AP Rocky could still rap, but whether he still cared to prove anything beyond the fact that he and Rihanna looked good together. TESTING had already split his audience down the middle, a record that traded his early swag for art-damaged experiments that some fans called visionary and others called empty. This album answers all of that with a shrug and a middle finger.

The paranoia on Don’t Be Dumb hits different because it isn’t performance. “Order of Protection” opens the record and Rocky comes in counting (“A couple lil’ trials, couple of leaks/Still in the field like I’m runnin’ in cleats”). “No Trespassing” builds on the same defensive crouch, a song that finds Rocky ready to relocate to Texas with his weapon, announcing “we ain’t lose in court yet” like a man still counting down to something. While the threat register stays high across both tracks, the tension feels lived-in rather than theatrical. You would think he’s someone who spent years being watched and has decided to stare back. Fresh? No. The boundaries-up, everybody-suspect playbook has been his default since LONG.LIVE.A$AP. What keeps it working here is the irritation underneath the bravado. He’s performing exhausted by the effort of seeming untouchable.

“STFU” drops the mask entirely.

“When are you and Rihanna?

Shut the fuck up!

Like, when’s the new album gonna?

Shut the fuck up!”

The song addresses the two questions that followed him everywhere, and the delivery doesn’t hide the annoyance. He rhymes about Haitians eating cats, about making sure his dogs eat, about Pateks and tail boots, but none of that matters as much as the exasperation in his voice when he mimics the public’s curiosity. Rocky made the tabloid circus part of the album’s texture. The resentment he carries toward scrutiny, toward every photographer, every commenter, every podcast host who asked the same two questions, bleeds into the production and never quite leaves.

Fatherhood enters the language without apology. “Stole Ya Flow” contains the album’s most direct acknowledgment: “Now I’m a father, my bitch badder than my toddler/My baby momma Rihanna, so we unbothered.” The bar lands hard because Rocky refuses to treat it as sentimental. He wraps fatherhood and relationship status into the same bragging framework he uses for jewelry and firearms. “Playa” pushes the idea further, defining parenthood as player ethic by rapping, “Takin’ care of your kids, boy, that’s player shit/One bitch, boy, that’s player shit/No baby mama drama, no new friends.” “Fish N Steak” opens with the same energy: “Now, my children, they already rich.” He’s folding RZA and Riot Rose into the flex and daring anyone to separate the personal from the posture. What’s changed is that the kids anchor everything else. What hasn’t changed is his refusal to soften his voice for anyone listening.

The courtroom shadows never fully lift. “SWAT Team” carries the sharpest line on the album about the trial, saying “You was there when the judge said, ‘Not guilty,’ it ain’t no jail for me,” delivered to an unnamed woman who apparently sat through the proceedings. “Air Force (Black Demarco)” takes a different angle: “Judge want my ass, smoke a pack in the court/Kickin’ in your door, all black Air Force.” The court language scatters across the record like shrapnel, and Rocky never sounds relieved. He sounds numb, maybe cocky, but mostly just tired of explaining. The not-guilty verdict didn’t erase the years of postponement, the public hearings, the questions about what happened on Hollywood Boulevard in November 2021. It just added another layer to the defensive posture he was already maintaining. When he raps about the legal system, he writes around the specifics and lets the mood do the work. The dominant feeling is survival, not vindication.

“Stole Ya Flow” doubles as Rocky’s grievance anthem and his most pointed commentary on ownership. The track accuses unnamed parties of biting his image and demands at least ten percent for the theft. The song’s central claim is that Rocky’s aesthetic got absorbed into the culture so completely that he no longer receives credit for inventing it. Whether that argument sounds sharp or petty in 2026 depends on how much you believe Rocky’s early influence still needs defending. The song makes its case without naming competitors, which keeps it from descending into rap-beef territory. Rocky stays inside his own self-myth, recounting all-black wardrobes, Chrome Hearts, Mary Janes matching Ferrari paint. The grievance is real, but the delivery walks a fine line between justified frustration and nostalgia for relevance.

The album’s attempts at tenderness mostly work. “Stay Here 4 Life” finds Rocky rhyming about paparazzi, five-percent tint, and asking a woman to move in and have kids—“Been thinkin’ you should move in, let’s mate and have a few kids.” Brent Faiyaz handles the vulnerable stretches, leaving Rocky free to keep his guard partially up even in romantic territory. “Punk Rocky” digs deeper into the isolation over an alt-rock production: “I cried alone in my truck, yeah/I felt alone in the front ‘cause I don’t know who to trust.” The production on both tracks leans melancholy, and Rocky’s voice drops its usual confidence without fully collapsing into confession. He earns the vulnerability because he doesn’t oversell it. The hooks carry the emotional weight while his verses stay grounded in styrofoam cups, megaphones, and the pattern of love turning into disappointment.

“The End” represents the album’s biggest thematic reach. will.i.am opens with “Got sick pigs in the ghetto, bucking us down/Dystopian, yesterday’s done now/Christian waiting for Christ to come down.” Rocky follows with his own sprawl: “Not many Blacks hit a billion, but still we packin’ in prison/The Klan got too many members, this’ all the devil’s agenda” and later, “I don’t know if public schools serving real food to the students, shit tastes like institution/How many school shootings happen in the hood?” Jessica Pratt adds ethereal vocals that frame the track as something grander than a rap song. The writing is messy, the transitions between ideas feel rushed, and the global-warming references land awkwardly next to the Klan bars. But the conviction is genuine.

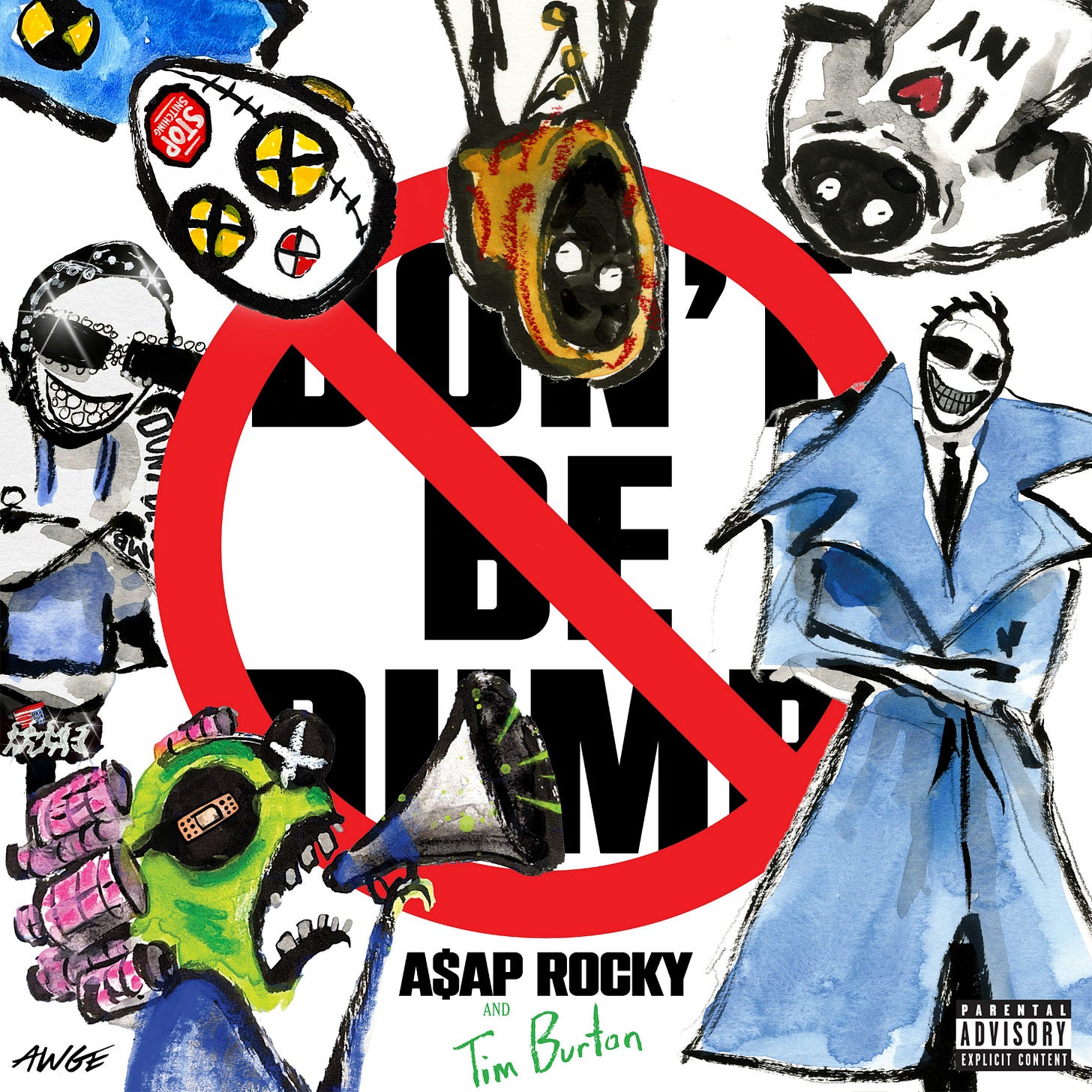

The swagger cuts through when it needs to. “Helicopter” brings back the playful Rocky who spins white tees and threatens Petey Pablo violence over Harlem production. “Stop Snitching” pairs him with Sauce Walka for a Houston collaboration that lands on informant culture with predictable but effective bars: “These days, these young niggas make snitchin’ cool/Youngin’s play by different rules.” “Robbery” features Doechii trading verses about fashion theft and romantic aggression, and her presence elevates the track beyond what Rocky delivers alone. Tim Burton designed the album’s cover art and Danny Elfman contributed scoring work, which explains why parts of the record lean into theatrical character voices and cinematic aggression. The visual-world ambition shows up in the tone more than the content, as tracks feel staged, lit from unusual angles, performed for cameras that may or may not exist. The production swings between trap, psych-soul, and something closer to film score without ever settling into one mode.

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Stole Ya Flow,” “STFU,” “SWAT Team”

Agree with every word in this review