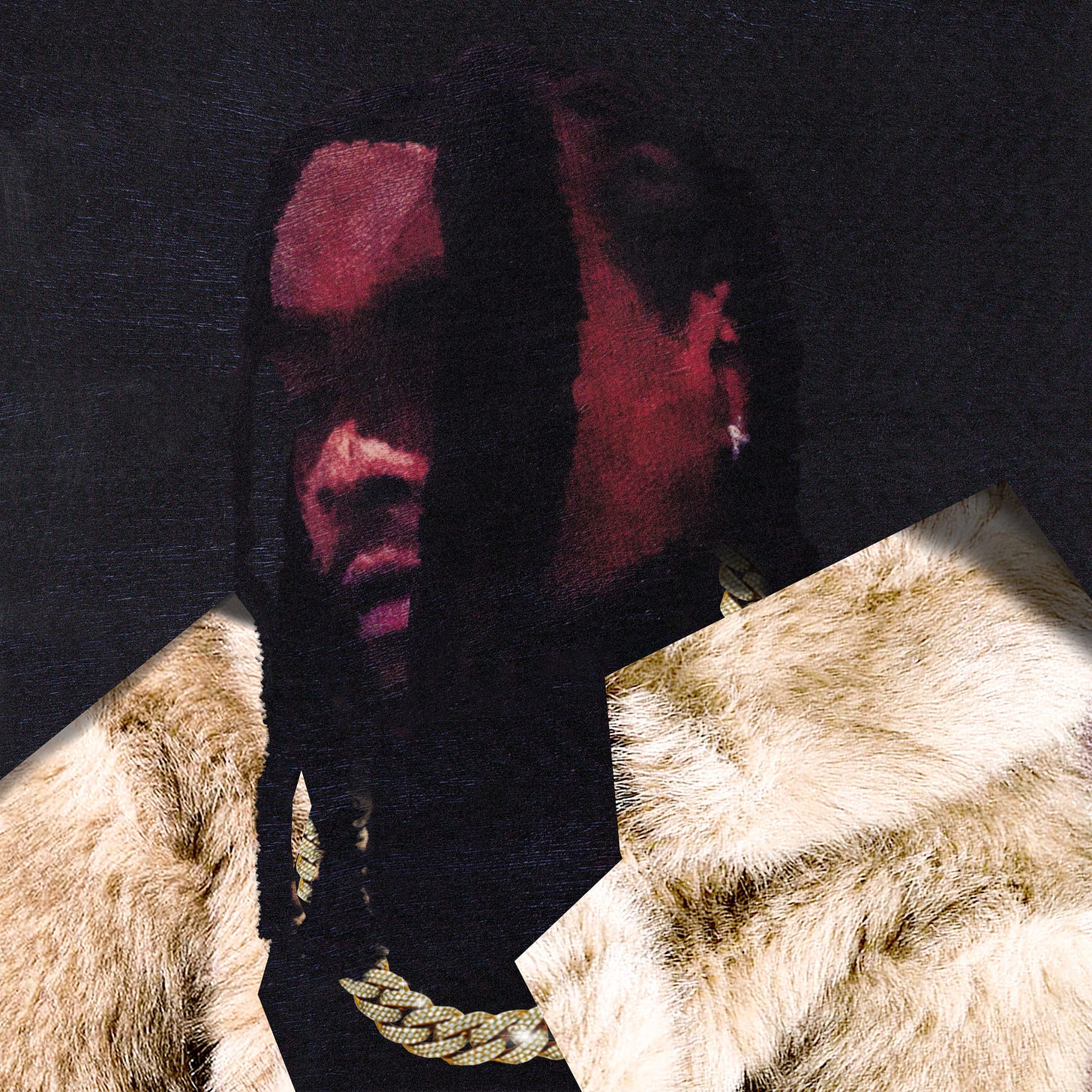

Album Review: Everything Is a Lot by Wale

After four years of relative quiet and a label change, Wale stands up as an emcee with history. Everything Is a Lot is not a reboot, but the weight he’s been holding in his life and in the industry.

Wale grew out of the D.C. circuits that moved on live percussion and call-and-response, and you still hear that instinct in the way he stacks cadences. He first caught attention in the mid‑2000s with “Dig Dug (Shake It),” a song built on the bounce of the go‑go scene that became a local hit and drew national attention to his mixtapes. They were Seinfeld‑themed, witty, sometimes arch, and they wore the percussion‑driven, horn‑flecked go‑go sound proudly. He once told Flavorwire that he consciously incorporates go‑go elements in his music, and evidently, the early singles heavily sampled 1990s go‑go records. In the early 21st century, he even became “the most vocal proponent of go‑go in hip‑hop.” By the time he signed with Maybach Music Group in 2011, he was already a mixtape legend with national television appearances and a charting single with Lady Gaga. His second and third albums (Ambition and The Gifted) debuted near the top of the Billboard 200, and he became a fixture of the national conversation.

But prominence doesn’t guarantee comfort. Four years ago, Folarin II closed his Warner/Maybach chapter. After that release, he quietly negotiated a new deal and announced his first album for Def Jam, explaining that “one of the underlying things is how heavy everything is in the world around me, my personal life, and the industry,” and that he carried all of that weight into this project. On Instagram, he wrote even more starkly: “Letting go of what I can’t change. Watching the industry become unrecognizable… people forgetting about me. Trying to find purpose in a thankless industry… new niggas actin like I’m a new nigga. Changing labels. Changing management. Finding love but scared to scar from it… The highs [and] lows… The most uncertain moments of my career are ahead of me.” These words are an artistic manifesto for Everything Is a Lot: he’s here to exorcise a load.

That heaviness appears immediately in the music. One of the earliest singles, “Blanco,” is the record’s most direct confession of self‑medication. Over a lurching rhythm, he shrugs off composure: “Drownin’ in sorrow… Back on the bottle… I’m not alone.” He stays locked on one idea, his verses sway between admission (“Tryna ease my mind… Got a threesome with these demons”) and deflection (“Here we go, back again… Got enough to go around, so tell all yo’ friends”). By using his own drunken party as a metaphor, Wale shows rather than tells his conflict: he knows the bottle numbs his pain, he knows he is running from solitude, and yet he still invites the whole club into his car. The song’s tension comes from his delivery, half-mumbled, half-sung, as if he’s fighting his own instincts. This is no longer the polished hustler of Ambition. We’re looking at a tired father calling himself out.

“Power and Problems” continues the internal dialogue. “My power, I never need no one/My problem, I never need no one/My trauma, I’ll never be conquered,” he confessed. Wale has always prized independence, but here he recognizes it as a problem: carrying power alone means carrying trauma alone. He flips a familiar proverb, “Heavy is the head, I’m told,” to describe the weight of expectation, a weight he also addresses in the album’s announcement. He acknowledges his defense mechanisms (“My intention with these women be pure/But my attention with these bitches just more”) and the therapy he half‑embraces, half mocks (“That therapy talk, stripped by like backdoor extortion… You thinkin’ you’ve all healed and really you gone ill”). The writing wanders like a mind in session. That wandering is the point by letting us into the interior rather than presenting a polished thesis.

Love songs on Everything Is a Lot are messy, too. “Where to Start” is built around a sample of SWV’s “So Into You,” but instead of leaning on nostalgia, Wale and Hollywood Cole use the motif to question his capacity for vulnerability. “I’m exercisin’ my vulnerability, but you spend all my energy… You still doubtin’ me like I’m the same nigga,” he raps, his voice scraping against the beat. There’s frustration—he feels his partner doesn’t see his growth—and a plea—he needs her recognition to confirm his change. The friction of that dynamic is what moves the song; he never resolves the tension, nor does he try to. On “Corner Bottles,” heartbreak is the teacher. He isn’t glorifying breakup recovery as he’s showing the emptiness of late‑night bottles and one‑night stands. The song’s second verse is full of details: unblocked numbers, “extra extra, it’s a movie tonight, you an extra,” that illustrate how he slides into distraction.

“Fly Away” is another relationship post‑mortem. While floating over Maxwell’s “Pretty Wings,” he opens by apologizing and admits that he might have weighed down his partner: “Nothin’ either you or I could change… Really, I was, maybe weighed you down… so fly away.” In the second verse, he connects his relationship patterns to the music industry: “Industry I gave it everything/And never got a thing.” This line echoes his Instagram post about a thankless industry. He conflates personal and professional betrayal, making the song resonate as both romance and career lament. “Like I,” featuring Andra Day, is the most tender track here. Day’s hook (“Have you ever been touched like I touch you… been loved like I love you”) opens space for intimacy. Wale responds with verses that alternate between romance and self‑critique. He even breaks the fourth wall to comment on his commercial prospects: “This album ain’t going platinum, no matter how this shit done/You hate what’s happening to me, can’t let it happen to us.” It’s a rare moment in which a rapper acknowledges commercial limitations in the middle of a love song, and it reinforces the record’s theme of juggling expectations.

Not every track is confessional. “Big Head,” a collaboration with Nigerian rapper ODUMODUBLVCK, is a boisterous Afrobeats‑inspired party record. ODUMODUBLVCK chants that women call him “big head,” and Wale jumps in with bilingual brags, referencing Bukayo Saka and Lagos nightlife. The energy is infectious, and Wale’s flows bounce differently over the syncopated groove. The track doesn’t carry the album’s heavier lyrical weight, but its placement matters beyond his heritage: it’s evidence that Wale hasn’t abandoned wordplay or swagger in his pursuit of catharsis. He can still talk slick and pivot between languages, especially on “YSF.” The same is true for “City On Fire,” which features Odeal. The song opens with Odeal contemplating self‑preservation—“At what cost do I choose myself and put on my armor?”— and Wale enters to describe a strained connection. He tells an ex that he isn’t jealous of her nightlife, then peppers the verse with the Yoruba word “wahala” (trouble), jokes about friends’ nosiness, and even jokes about watching Martin when he hears “what’s up.” He acknowledges pettiness and moves on.

Stylistically, the record sprawls. There are those call‑and‑response hooks, but there are also Afrobeats melodies, R&B samples, orchestral interludes, and trap drums. Wale’s influences have always been broad. The jump from being introspective to the brash records, and then to a love song, can feel jarring. Even when he raps about parties, he slips in references to exhaustion. When he sings about love, he ties it back to career anxieties. When he brags, he mixes the braggadocio with self‑doubt. His songwriting choices are sometimes uneven. Wale moves between sharp, self-exposing lines and moments where he circles an idea without pushing it further. But there are stretches where he leans on familiar setups without the same level of specificity. The unevenness comes from that contrast, where some verses drill directly into the wound, others slide back into broad postures that don’t carry the same weight. Nothing about the hooks creates that imbalance. It’s the variance in how precisely he chooses to show himself from bar to bar.

When the album explores fatherhood and family, it does so indirectly. In “Conundrum,” he hints at the complications of co‑parenting (“My baby mother told her new husband she had to move on… that’s the price of this life, I pray for guidance”) and his own emotional distance (“I could love you to death, but still I gotta get ghost sometimes”). The verse is full of questions about love versus lust, and he ends with the line “this is quite the conundrum,” again refusing to provide closure. He admits his heart is colder than most and that he is self‑aware but still selfish. The honesty of such admissions shows the “reckoning” he promised. When he confesses “Survivor’s remorse, that’s all I be thinking; living too hard, hear dying is easy” in the heartfelt “Survive,” he says it plainly. There is no attempt to dress pain in a poetic flourish. The avoidance of extended metaphors makes the record feel raw.

Every record has imperfections. Some songs here wander without a clear melodic anchor, others lean heavily on guest hooks (like Leon Thomas stealing the show on the Goapele-sampled “Watching Us”). There are moments where Wale’s wordplay veers into filler. Yet the bravery of documenting his internal dialogue at this stage of his career outweighs the missteps. He has not abandoned the bravado or the swagger that once had him rapping alongside Roscoe Dash and Rick Ross, but he now layers that bravado with vulnerability. When he tells us, “I be out when I’m out, you see me try play it cool,” he is still performing but is aware of the performance.

Solid (★★★½☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Blanco,” “Power and Problems,” “Like I”