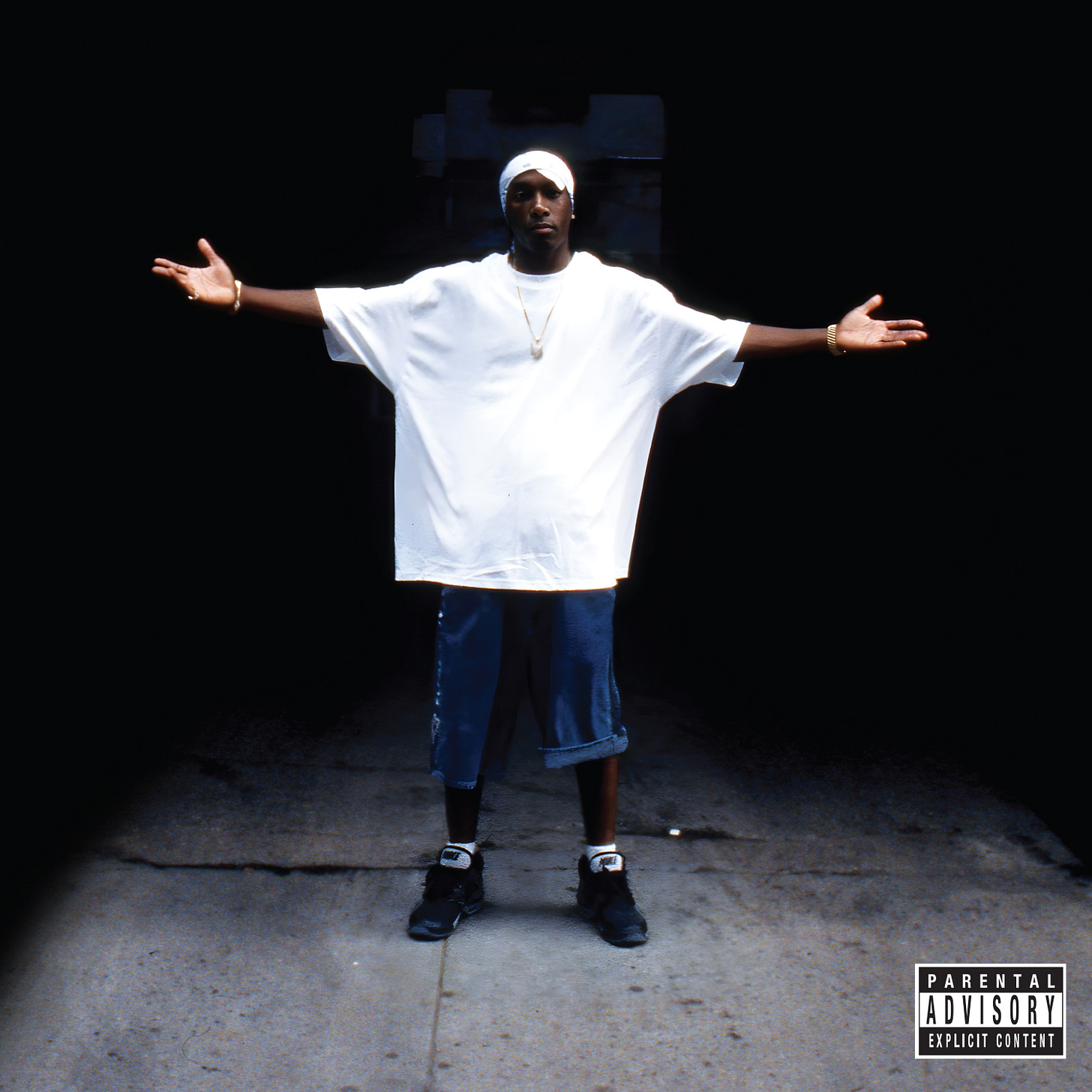

Album Review: Harlem’s Finest: Return of the King by Big L

Twenty-six years after his death, Big L’s voice returns—restored, re-spliced, and surrounded by living giants trying to prove they still remember how sharp his tongue was.

Nas’ Mass Appeal imprint spent 2025 chasing ghosts. Its Legend Has It initiative promised seven new albums by seven icons, from Slick Rick to Mobb Deep, culminating in a Halloween drop for Harlem’s fallen son. Lamont “Big L” Coleman was murdered in 1999 at 24; he released only one album in his lifetime, but his posthumous catalogue and the legend of his rhyme schemes have grown with every mixtape and freestyle leak. The campaign’s marketing positioned Harlem’s Finest: Return of the King as a full‑circle victory: Nas’ label working with Big L’s family to reclaim unmixed files, clear samples, and pay producers properly. It also sits alongside new records by Ghostface, Raekwon, De La Soul, and others, with a Marvel comic tie‑in. By the time it arrived, fans knew the backstory: there is no hidden vault of complete Big L songs; what exists are freestyles and demos. Mass Appeal’s solution is to drape those verses in new beats and pair them with star‑powered guest spots. Most of the time, it feels like a celebratory museum exhibit, rehashed from Return of the Devil’s Son fifteen years ago, though occasionally it feels like a wax museum (almost leaning towards Biggie’s Duets territory).

The opener, “Harlem Universal,” sets the tone. Gritty boom‑bap drums and a moody bassline wrap a sample that loops like an alleyway siren, creating a tense street atmosphere. Big L bursts in unfiltered: “I be twisting bitches a lot… I be dropping like early August, late July, with raps that’ll make you cry, hate you, die.” The verse is classic 139th‑and‑Lenox L—braggadocio and misogyny tumble over internal rhymes, and his flow darts like a dice game. Herb McGruff, a Children of the Corn alumnus, matches the energy with stick‑up talk and chain‑snatching. The production channels the basement grit of Lifestylez ov da Poor & Dangerous, and hearing L’s 20‑something voice rapping about “new shit going past gold” reminds you of just how hungry he was.

A similar dissonance runs through the marquee single “U Ain’t Gotta Chance.” On paper, it’s a dream: L finally trades bars with Nas, the Queens rapper who once admitted that Big L scared him when he heard him at the Apollo. In reality, the track is two different timelines soldered together. Big L’s verse is lifted from a 1997 Tim Westwood freestyle, full of hilarious boasts—“You won’t be rich as me if your whole crew put your cheese together”—and threats to stick a gun in your mouth. His rhyme schemes are agile, and his punchlines still sting, but he never engages Nas because he never knew this beat. Nas, meanwhile, delivers a new verse about forming a venture‑capital firm and leaving his seat reclined. His technical execution is flawless, but the theme sits uneasily alongside L’s street‑corner talk; he even confesses that recording with a ghost put him under “pressure.” The co‑produced beat by G Koop, 2One2, Al Hug, and Zach Niess slaps, but the splice job is obvious. It’s a highlight because of nostalgia, not chemistry.

“Fred Samuel Playground” (produced by one of the hip-hop producer MVPs, Conductor Williams) feels more organic. Big L boasts about walking around with “six thou’, sippin’ on Cristal” and “luxury whips, Motorola flips,” painting the opulent side of hustling. Method Man responds by twisting the playground metaphor into a cautionary sermon: “This shotty ain’t a shotty, it’s a stick now… Wash ’em up until it dawned on me I was finished with them dish towels.” His verse is playful yet menacing, and the Conductor beat has a dusty soul loop and heavy drums reminiscent of Wu‑Tang classics. Because both verses were likely recorded around the same time, the track feels like two MCs in the same cipher, even without a hook.

Mass Appeal wisely includes moments that show L’s emotional range. “All Alone (Quiet Storm Mix)” slows things down with a late‑night sample and R&B singer Novel on the hook. L admits, “I need somebody I can call my own… basically I’m all alone.” He talks about wearing a “phony smile” and watching friends vanish, revealing vulnerability rarely associated with his bulletproof persona. The introspection continues on “How Will I Make It (Park West High School Mix),” a sobering narrative from the perspective of a 10‑year‑old. His mother smokes crack, and his father “went out for a fast snack and never brought his ass back.” L wanders the streets in dirty sneakers, ashamed and hungry, and by the second verse, he’s robbing people for food. The hook’s repeated question, “How will I make it? I won’t, that’s how,” strikes harder than any punch‑line. These tracks justify the album’s existence; they remind listeners that L wasn’t just a punchline machine—he could illustrate the systemic pressures of Harlem poverty with startling clarity.

Then there are the freestyles. “7 Minute Freestyle” with JAY‑Z is the centrepiece for purists. Recorded on Stretch & Bobbito’s 95 show, it has long circulated on cassette; now it’s cleaned up and pressed to wax. L unfurls a torrent of bars about “puttin’ thugs in ditches when my trigger finger itches,” attacking clowns with lead pipes and leaving streets “drug‑related.” His imagery is over the top—he jokes about being so ahead of his time that his parents haven’t even met—yet his breath control is surgical. JAY‑Z counters with a charismatic verse full of zorro metaphors and acrobatic schemes, but he’s clearly the guest. As a time capsule, the track is thrilling; as part of an album, it’s seven minutes of unedited radio rap that interrupts the flow, despite the Miilkbone beat being reproduced.

“Forever,” the song that sparked the most debate, is the album’s big swing. Posthumous Mac Miller duets are delicate to execute—Circles was a careful farewell—so pairing him with Big L risks the same Frankenstein effect. Mac opens with a playful, weed‑laced verse, comparing his colourful wardrobe to a canvas and taking a player’s ball through “Cory and Topanga” references. Pale Jay croons an airy hook. When Big L enters, he goes straight back to street talk: “My whole entourage is lost from here to Vegas… Feds got my phone tapped.” He also declares that his chain has “mega ice” and his chrome rims push like Christopher Nolan’s Tenet. There’s little thematic overlap with Mac’s verse; the track feels like two separate songs stitched together. Some fans argued that the pairing was disrespectful, while others were excited to hear both voices in one place. As audio, it’s more novelty than revelation.

The back half of Harlem’s Finest leans heavily on freestyles and mixtape fodder. “Doo Wop Freestyle ‘99” has L rhyming about guns, sex, and loyalty, with lines like “Every bitch that I’m fuckin’ with now is cock‑suckin’” and the boast that he’s “so ahead of my time my parents haven’t met yet.” Joe Budden’s name appears on the packaging, but his voice is just talking about the veteran's influence. The “Stretch & Bob Freestyle ‘98” is full of shock‑rap—L threatens to shove a broom in a snitch’s backside and cracks jokes about beating up teachers for giving him bad grades. The juvenile violence hasn’t aged well, but the wordplay remains nimble. “Grant’s Tomb ‘97 (Jazzmobile)” pairs L’s charismatic boasting (“Jeans be saggin’ off half of my ass… I’m gettin’ cheddar galore like never before”) with a sharp verse by Joey Bada$$, who channels ‘90s boom‑bap while claiming he’s “rappin’ like it’s my last minutes alive.” The generational gap is jarring—Joey’s flow is methodical, not improvised—but his appearance proves that Big L’s influence lives on.

A gem for completists is “Live @ Rock N Will ‘92.” Recorded when L was barely out of high school, the mix captures him ripping through multi‑syllable rhymes about ripping MCs like Campbell’s Soup and comparing his bars to a “robot” that’s “so hot.” Hearing his teenage voice controlling the microphone like a seasoned veteran underscores how rapidly his skills developed. The closing bonus track “Put the Mic Down” features Fergie Baby and Party Arty trading battle bars with L. He instructs wannabes to “put the mic down and fight now,” warns that he’ll “blow off more than half of your brain for acting insane,” and boasts of running with cats who’ll “attack in the rain.” The younger guests bring modern slang, but the hook’s chant and Ron Browz’ sound can feel generic, closing the album with a shrug.

The Legend Has It campaign contextualises L alongside peers like Ghostface and De La Soul, emphasising hip‑hop’s lineage. For younger hip-hop fans who know him only through myth, the compilation is a primer on why his punchlines were revered and why JAY‑Z and Nas held him in high esteem. But the record also highlights the limitations of posthumous projects. There really aren’t “unreleased gems” you think it is. There are radio freestyles and mixtape verses that die‑hard fans already memorize. The new production occasionally overpowers the raw recordings, and the star‑studded collaborations rarely feel like genuine conversations. Mac Miller and Big L have nothing in common, and the “U Ain’t Gotta Chance” splice invites constant comparison to the original freestyle. It’s a respectful museum piece rather than a living album. If you’re a completist or if you enjoy hearing old freestyles restored, you’ll appreciate it. If you were hoping for new chapters in Big L’s story, there isn’t enough material left.

Above Average (★★★☆☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Harlem Universal,” “Fred Samuel Playground,” “7 Minute Freestyle”

Perhaps it's fitting to release a ghoulish album on Halloween?