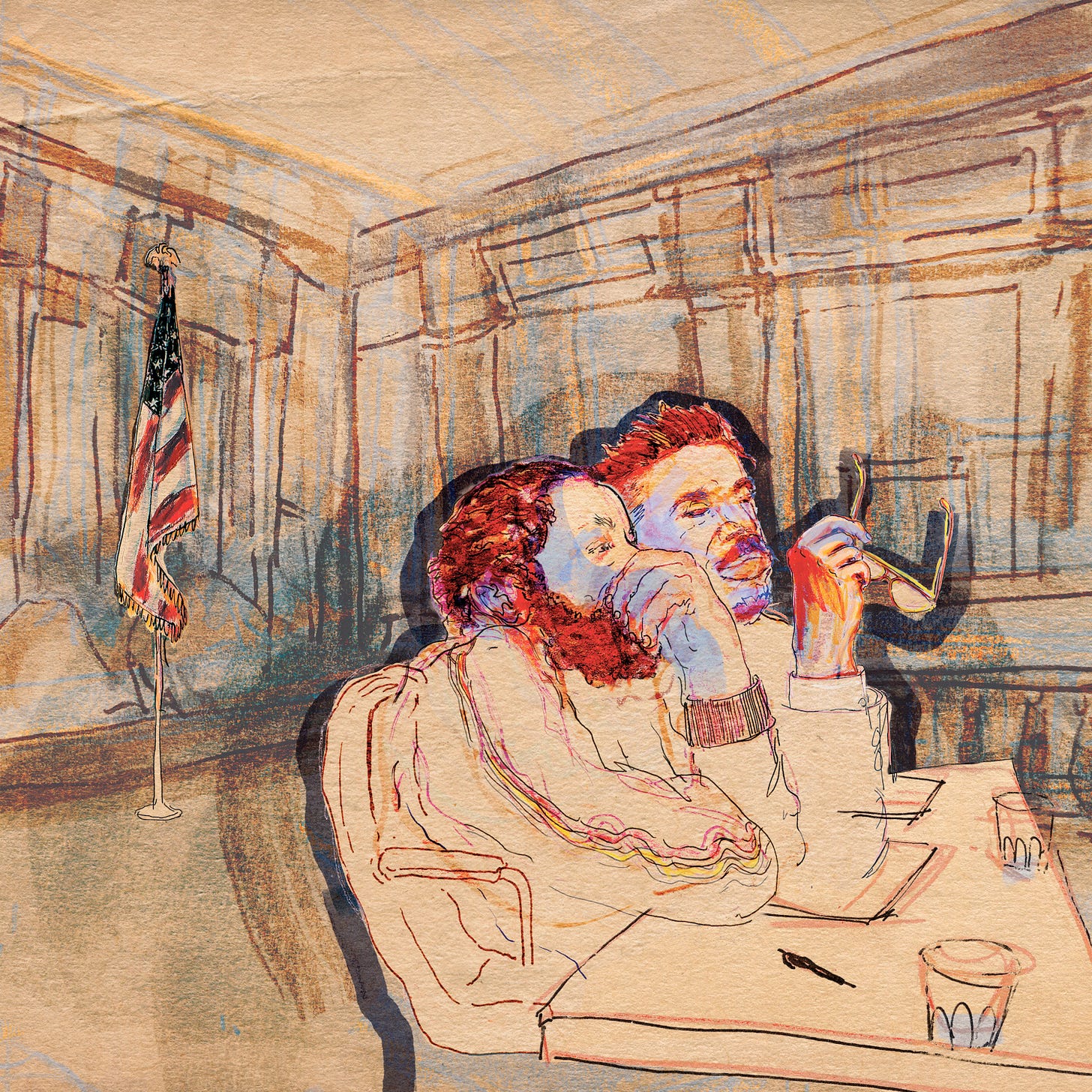

Album Review: Mercy by Armand Hammer & The Alchemist

Armand Hammer’s second album with The Alchemist, curated around a theme of rust and grace. A new bond is tested, searching for mercy somewhere between the church and the street.

You don’t listen to an Armand Hammer record so much as you move through it. The doors have different weights; the light bends in unexpected directions. On Haram, The Alchemist’s production sharpened their abstract poetics by providing a haunted yet accessible backdrop, allowing the duo to dive into taboo subjects—power, violence, societal rot—without being swallowed. That record’s standouts, like “Falling Out the Sky” and “Stonefruit,” achieved resonance by balancing unsettling and atmospheric textures. Two years later, We Buy Diabetic Test Strips exploded that cohesion. Fifteen producers scattered the duo across glitchy drum collages, dubby jazz, industrial clang, and ambient haze. “Landlines” set the surreal tone with reversed samples, ringing phones, and pitched vocal samples while ELUCID reflected on 1990s childhood and woods dropped the deadpan line “Rather be co-dependent than co-defendants.” The opener melted into “Woke Up and Asked Siri How I’m Going to Die,” a dreamy collage where ELUCID repeated “I ain’t seen the bottom yet” while the track itself faded like an interrupted dream. Later songs like “When It Doesn’t Start With a Kiss” kicked in mid-verse with harder drums, and the record’s density often felt like navigating a warehouse where each room belongs to a different architect. For many, that fragmentation was invigorating; for others, it hinted at the limits of abstraction.

Mercy arrives not as a reset but as a reckoning. The Alchemist is once again the sole architect, yet he refuses to build a cushioned environment. Instead, he folds gospel samples, off-kilter piano loops, and spectral hums into something that feels rusted and holy. The opening, “Laraaji,” hangs on a sustained guitar vibrato and a low-riding drum pattern; ELUCID swerves through surreal images of a meritocracy myth and tender-headed Black boys sleeping under the gingko tree. woods counters with a warning delivered like a shrug—Should have killed me when you had the chance. The beat doesn’t cushion these lines, it amplifies their menace, turning the intro into a gut check. As the song fades, the memory of Diabetic Test Strips lingers; this is a duo practiced at bending time. But here, the Alchemist’s loop doesn’t sprawl. It presses against the words.

The claustrophobia continues on “Nil by Mouth,” a song that trudges like a funeral procession. There’s no full drum kit, just a gritty sample that crumbles as it loops. woods paints a picture of predators, then drops in the line about crocodiles weeping while they eat your salty tears. ELUCID asks, with a bitter laugh, if everything is justified when you’re starving. The Alchemist laces a ghostly vocal loop underneath their verses, not to soften the blow but to underline it. This is where Mercy’s concept begins to reveal itself: mercy isn’t forgiveness or weakness; it’s a state of tension between hunger and relief. The beat’s persistent decay upholds the moral corners woods draws; you can’t mistake his cynicism for detachment here. Every syllable lands like a sharp edge.

There are pockets of grace, but they’re ambivalent. “Calypso Gene,” featuring Silka and Cleo Reed, coasts on a layered, almost tropical groove. The voices in the hook float in and out like spirits. ELUCID’s verse uses water as both a lifeline and a territorial divide—baptism and blockade in the same breath. woods answers with images of fences and border patrols. The contrast is delicate: one rapper melts syntax until it becomes vision, the other assembles visions like a legal brief. The Alchemist slips in a few guitar notes that shimmer and vanish. It’s a beautiful track, but the beauty is complicated by its subject matter. Mercy is full of such frictions.

“Scandinavia” is a showcase of their chemistry. The beat is skeletal, built on kick drums that slam like a door in a dark room. ELUCID’s flow is percussive and restless; he fires off lines, pauses mid-bar to let the negative space do work, then charges again. woods wraps his verses in longer sentences, stacking historical references and puns. They trade verses like a baton, pushing and pulling each other forward. When they lock into a rhyme scheme together, it’s narrative momentum, not a technical attribute. The song never fully explodes; it simmers. The tension between their cadences mirrors the tension between claustrophobia and grace. Each tries to carve out space in a beat that refuses to sprawl.

The heart of the record is “Dogeared.” The production is understated, a loop that feels like it could unravel at any moment, leaving more air around the verses. ELUCID uses that space to reflect on his relationship with language. His verse shifts in tone mid-sentence, bends rhyme schemes, and circles around a question: why keep doing this? woods answers indirectly, telling a story about his week—making breakfast for his kids, scrolling his phone, starting a novel, and abandoning it. Someone asks him the role of a poet in times like these; he’s still grappling when the verse ends. That openness is rare in their catalog. It’s one of the few moments where the self-mythology of Armand Hammer slips, and you see the working artists. The Alchemist resists filling the empty space; he lets the question hang. Mercy is full of sharp lines, but it also honours the discomfort of leaving things unresolved.

“Crisis Phone,” with Pink Siifu, demonstrates another facet of this record’s emotional range. The beat is built on mournful strings that rise and crest, like a film score for a stalled rescue. Siifu’s hook is spoken more than sung, a list of grievances delivered in a voice that sounds both weary and resigned. woods drops sardonic one-liners with “Miss me with the mystery meat,” but he also paints a landscape of civic dread—crumbling infrastructure, disinterested authorities. ELUCID’s verse feels like it’s dialing but not connecting. The hook returns, the strings swell, and you realize there’s no real resolution. Mercy respects that dread; it doesn’t try to wrap it up in cathartic crescendos.

Yet the album’s final stretch makes a compelling case for Mercy’s ambitions. “Longjohns” brings in cosmic jazz-psych textures and a choral refrain urging the listener to tighten up. Featuring Quelle Chris and Cleo Reed, it oscillates between playful and severe. woods’ verse leaps from a crowded subway to apocalyptic images with no warning. ELUCID weaves in personal anecdotes with incantations. The Alchemist samples a faint organ, adding a gospel undertone that hints at deliverance even as the lyrics resist it. In the context of the record, the song works as a counterweight to the bleakness of “U Know My Body,” which catalogues everyday cruelty with chilling precision. On that track, there’s a hook, but it behaves like a trap, repeating until it becomes a litany. The emptiness in the beat—just a few muffled drums and a haunted vocal sample—makes their descriptions of police harassment, medical malpractice, and generational trauma all the more suffocating. This is Mercy at its most punishing and most necessary.

The single, “Super Nintendo,” could have felt gimmicky—it’s built entirely around a looping 16-bit synth motif. Instead, it lands as a warm exhale. The Alchemist turns the motif into a lullaby, and woods uses it to examine his own evolution: “Rewind my old raps/Wonderin’ where that brother’s at.” He sounds like he’s flipping through his own discography, measuring growth against loss. ELUCID answers with a verse that blurs images of childhood consoles and present anxieties, as if to say nostalgia is always tangled with dread. The track doesn’t resolve tension so much as accept it. The beat loops one more time and cuts. Mercy ends not with an answer but with a shrug: we did what we could; the world keeps spinning.

Throughout Mercy, The Alchemist continues to find new emotional registers for Armand Hammer’s language. Where his production on Haram struck a balance between unsettling and atmospheric, here he emphasises texture. Gospel choruses are chopped and rearranged into dissonant spells. Pianos are detuned and looped just long enough to make you dizzy. Percussion arrives in short, insistent bursts or doesn’t arrive at all. This approach forces woods and ELUCID to adapt. When they lean into abstraction, the sparse beats leave them exposed. When they get direct, the beats frame their words like verse on parchment. It’s a re-wiring, not a nostalgia trip. You can hear echoes of The Alchemist’s smoother work with other artists, but he pushes further into discomfort here, and that push coaxes new vulnerability from his collaborators.

Some of Mercy’s power comes from its restraint. After the maximalism of We Buy Diabetic Test Strips—with its field of producers and guests—the controlled environment makes every deviation matter more. With this second pairing, it is a coherent, daring work that brings together two of rap’s most adventurous lyricists and one of its most inventive producers, interrogating their craft and their world with renewed urgency. woods and ELUCID don’t stand outside and comment on the chaos; they walk through it and report from within. Their humor is often wry and barbed, their cynicism tempered by glimpses of tenderness. It’s exhausting and exhilarating. You leave the record with questions rather than answers, and that’s part of its gift.

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Laraaji,” “Dogeared,” “Longjohns”