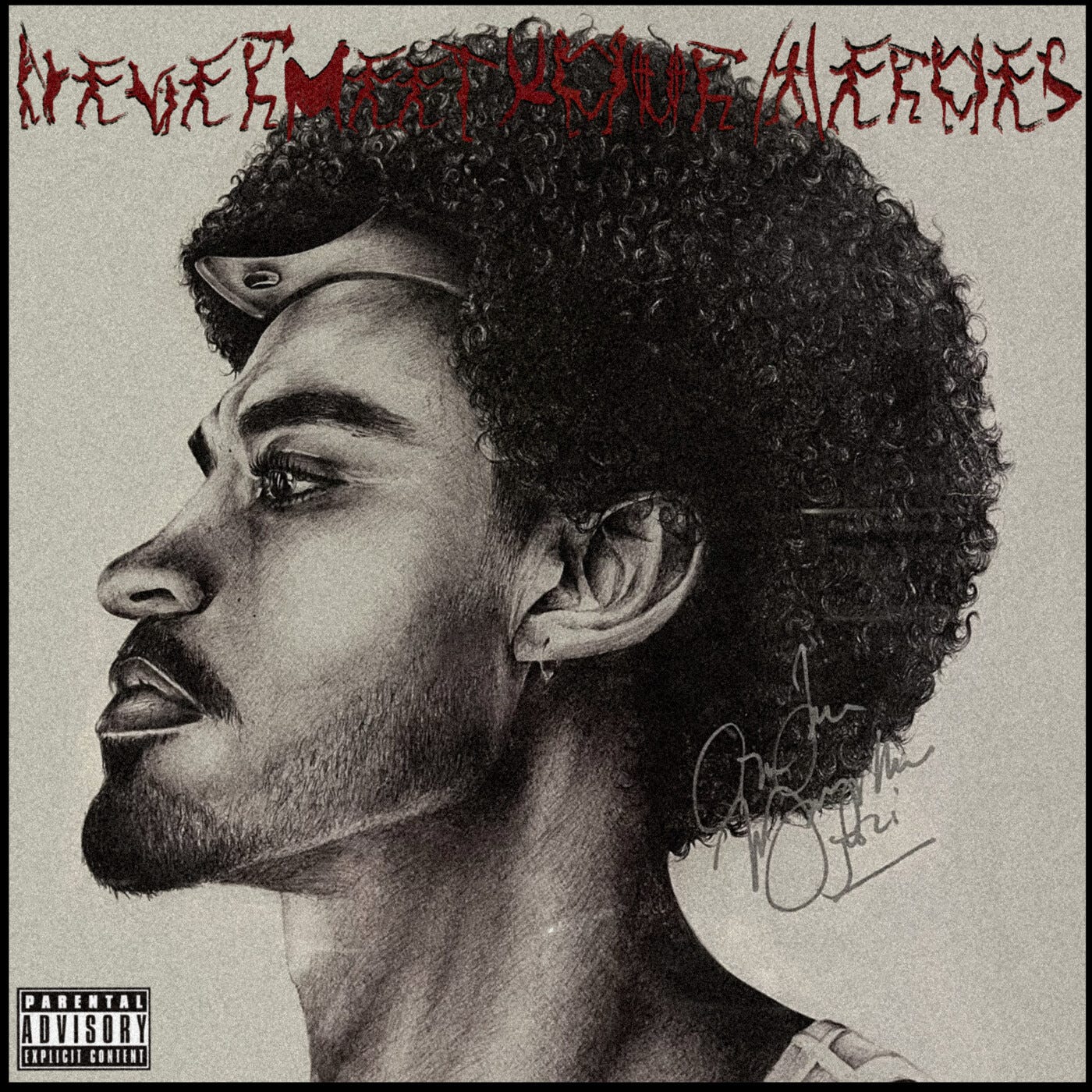

Album Review: Never Meet Your Heroes by Shane Eagle

Shane Eagle sounds like a man who knows what he’s carrying—grief, faith, family, expectations, and focused lyricism make it one of the most compelling hip‑hop releases of the year.

With years removed from AKiRA and its buoyant introduction, Shane Eagle doesn’t arrive with the same weightless optimism. He is a father now, the owner of an independent label whose debut went gold, and a rapper whose city has grown up with him. His long-awaited release, Never Meet Your Heroes, lands not as a victory lap but as a reckoning. It folds faith and fatherhood into every bar, exhumes the ghosts of Johannesburg’s past and his own, and channels a calmer, sharper hunger.

“The golden city, South Africa’s Johannesburg, 70 years have brought a small township to rank with the world’s richest cities,” intones the vintage voice on the opening “Intro.” The archival broadcast evokes the mythology of Joburg as the city of gold; Eagle loops it into a meditation on inheritance and survival. When the sample fades, he answers with the tail end of “Son of Yahweh”: “Keep your dream alive/Niggas say it’s gonna die but it’s still alive.” This mix, as a colonial narrator celebrating wealth and a modern rapper asserting spiritual inheritance, frames the record. Eagle’s tone is different from what it was, more gravelly and less eager to please. He raps about reading Napoleon Hill and dedicating his daughter, Giovanna, to the Lord before “get[ting] back to making M’s,” a line that marries discipline with domesticity. The production mirrors this duality with dusty soul samples and mellow keys supporting confessional verses, while crisp drums punctuate declarations of resolve.

That balance between gritty self‑storytelling and devotional chorus runs throughout the first act. “Ride Out” is a flex. Eagle admits he “made it out the come‑up” without owing anyone but God, his wife, and his daughter, yet remembers his father’s last tears and imagines where he might have been had he stayed in Africa instead of chasing opportunities abroad. His anger at the music industry is respectable (“Fuck your Shane Eagle boycott, I’m Eminem”), but the hook never devolves into mindless bravado. Instead, he repeats a taunt (“I could burn this bitch down if I want to”) over a haunted instrumental. Rather than revel in destruction, he uses those lines to show how much he has to lose. When he calls out rappers “cosplaying as goats” and labels who only see him as a commodity, you can hear the frustration of an artist who runs his own label, yet still has to fight gatekeepers. The crisp snares on the track hit like smacks at those gatekeepers; the dark synth bass hums like the engine of his hooptie ready to ride out. The rage here is controlled—calm enough to be persuasive, focused enough to be dangerous.

Shane Eagle’s storytelling sharpens further on “Lil D.,” which plays like a short film about adolescent friendship and divergent paths. Over a classic boom‑bap beat laced with soulful humming, he revisits riding around Johannesburg in a friend’s grandmother’s Toyota, hot‑boxing the windows and sharing dreams while bumping The Chronic. D was the older cool kid destined for greatness, until a robbery gone wrong landed him in prison. Eagle refused to ride along—a split‑second decision that saved his life and set him on a different trajectory. Years later, visiting D behind glass, he tells him about his father’s passing and his own success; D is stuck reliving the decision that derailed his life. “He might have to do the shit that got him there in the first place,” Eagle admits grimly. The song’s restrained production (dusty drums, a warm bassline, and a wistful sample) feels like a memory replaying on an old projector. It demonstrates Eagle’s ability to let texture mirror transformation: as he names loss after loss and delivers a resolution (“The rest is history, my nigga, hello”), the beat breathes, anchoring the album’s theme of transmuting loss into clarity.

“Afro Comb” faces generational pain head-on. Outside of spitting “there’s still love in broken homes, bricks of promise and afro comb,” he unpacks childhood trauma without melodrama. He admits he never felt love for his mother because she lost her father to suicide at sixteen and grew up emotionally detached. In a quietly devastating line, he asks God to free his mother from her bondages so “we could all move forward,” turning therapy into prayer. He expresses his desire for community healing: he wants to see his people free from chains, making millions and caring for their seeds, but notes that most of them “learn what they see on the screen.” This track shows the album’s central movement: Eagle doesn’t just recount pain; he conjures a sonic environment where pain can be acknowledged, held, and released.

“Arrival” and “Outraged” comprise the album’s middle act, where the discipline of a self‑built label meets righteous fury. On the former, he declares, “I’m God’s son but I’m givin’ ‘em hell,” then skewers fake record executives, color‑blind platitudes, and false gangsters. His flow pulsates between double‑time bragging and clear enunciation when he lands on a moral lesson. He recounts watching his sister being lowered into a hearse the same year his daughter was born, a juxtaposition of death and life that underpins his newfound sense of purpose. On “Outraged,” he tackles identity politics head-on, rejecting superficial racial labels. Born to mixed‑race parents, he refuses to be boxed in; when he travels to the United States, they call him Black, while in South Africa, he’s called colored. “Fuck representin’ a race, I represent all people ‘til we’re all equal,” he spits, before naming the universal laws that he’s mastered. His denunciations of faux activism, rap opportunists, and jewelry-obsessed rappers are delivered with a snarl, but he grounds his critique in spirituality. He holds the sun within his soul and blinds false prophets with its light.

The album’s spiritual center lies in the following three songs. Eagle trades anger for meditation. Over sampled vocals and gentle percussion, “Alchemy” finds him realizing that true wealth isn’t financial: “What could possibly be more important than catching the sunset with Gia on my shoulders?” He reminds himself that chasing the next thing without appreciating what’s already in front of you leads to misery. That theme continues on “Choose God,” which opens with a hook that his presence is a gift like Christmas time, he raps for his niggas doing time. In the verses, he describes helping his mother when she loses her direction; the track culminates in a spoken prayer asking Jesus to wash him clean. A hush descends over the mix; the instrumentation drops to little more than sustained chords and subtle chimes, mirroring the silence of prayer. “Let There Be Light” flips the introspective energy into a pep talk to himself. “Remember when you chose your heart over choosing fame?/That was the greatest decision you could’ve ever made,” he tells himself, layering voices to create call‑and‑response. The beat is airy yet anchored by a boom‑bap kick, allowing his baritone to float. He takes pride in taking the road less traveled and reminds himself that the sun shines alone, yet still shines.

One of the record’s most playful detours is “Ronnie Fieg (Interlude)” and the two‑part “Cognac & Cigarettes.” The interlude is a breezy vignette where he riffs on the joys of making music at home (“My first classic I cooked up in Alexandra/My second classic Giovanna/Word to my mama”) and tips his cap to U.S. cultural references. It sets up “Cognac & Cigarettes,” a collaboration with Stogie T. Stogie opens with a dense verse full of double meanings and African liberation references, ending with the line “Skip legs and still run circles ’round you bitches,” a meta‑joke about leg day and outrunning peers. Eagle answers by rapping about building a five‑story crib, hustling for dead presidents, and turning a garage that once housed a trap into a museum piece. The interplay is friendly but competitive; where Stogie’s verse is ornate, Eagle’s is direct. The beat evokes classic New York hip‑hop with a South African swing. He references Lupe Fiasco’s “Kick, Push,” Miles Davis, and Jeff Koons; he calls himself “a unproblematic genius” while quoting scriptures. There’s a smirk in lines like “My girl the only one who could top me,” but even his boastful moments return to prayer: “Give praises to the Most High, think He wants me to shine.”

Another potent guest spot arrives on “Wolves” with Cape Town’s YoungstaCPT. Eagle opens with a string of lupine metaphors: throw him to the wolves and he’ll come back leading the pack; he juggles the word in one hand and a crown in the other. His Gemini temperament and juggernaut persona allow him to deliver industry critiques (“Who's the one that showed niggas we can tour overseas?”) while boasting about staying independent. The beat is percussive and menacing. YoungstaCPT answers with a verse that references the Cape’s wine country and the violence that shadows it, laments internet toxicity, and celebrates raising children instead of clubbing late. He calls himself the Key Maker, a Matrix nod, and flexes Keanu‑like coolness. The track’s energy is feral yet grounded, bridging regional styles through shared hunger.

The final act of Never Meet Your Heroes is its most personal. “Wailers” sees Eagle pivot from defiance to vulnerability. “To be legendary” is sung like a lullaby, then he raps about killing rappers who’ve already killed themselves with mediocrity. He refuses to believe in fairies or legends, wonders whether people recognize legends in the present, and acknowledges that haters will always exist. The instrumentation floats on boom-bap guitar loops, a nod to Bob Marley’s Wailers. When he raps “Any slums you go to they gon’ say, ‘Jesus the one,’” he ties his own rise to a spiritual mission. The song’s third verse circles back to the theme of survival: he’s got a pocket full of “Madiba faces” (Nelson Mandela notes), but he still recognizes where he stands in the struggle.

With “Holy Fire,” the spiritual and rap sides combust. “This that flow that could bring that old Ye back/Sunday services with uncle, sippin’ cognac,” he raps over a mellow‑inflected loop. He was raised around pulpits and .9 mm pistols; his God is a jealous God with no idols. He offers one of the album’s most vivid images—a white horse not as a symbol of a Ferrari but as an ancestral sign—and nods to Afrofuturist mythologies, comparing himself to a descendant of the Anunnaki. The production is thick with piano key chops and rattling percussion. Then “Charizard” lightens the mood by comparing himself to the fire‑breathing Pokémon; he signs an autograph on a Charizard card and wakes up spitting fire. The bars are witty and playful, as he “went yellow again like I’m Super Saiyan 2,” but he grounds the punchlines in reality: he still keeps a Glock, still prays for his enemies, and never calls himself the GOAT; he lets the streets decide.

“Tough” is pure bravado: he’s wearing a Nike vest, checking his timepiece, and bragging that labels should have signed his shadow if they wanted hits. The minimalist beat leaves room for his cadence to bounce; his laugh after declaring himself the big dog is contagious. Yet even here, he grounds the flex in domestic life: he spends time with his daughter before getting back to the money. The final track, “My Daughter’s Hand,” is the record’s emotional apex. Over warm, unadorned chords, he confesses that nothing is more important than holding his daughter’s hand. Until you have a child, he tells us, you won’t understand. He thanks God and admits he still carries trauma he doesn’t want to pass down. He flips between describing Gia as “a precious sample I loot” and acknowledging how selfish and selfless he has been. When he raps, “A billion diamonds couldn’t comprehend your worth/I travel through these lifetimes just to go and search/For my daughter’s hand,” the metaphor is cosmic yet intimate.

At nineteen tracks and fifty‑six minutes, Never Meet Your Heroes is an expansive project that occasionally drags. “Haters Heartbreak,” for instance, feels functional rather than revelatory, and the sexual braggadocio in its later verses sits awkwardly next to the album’s more tender confessions. The consistent return to religious imagery may test those who crave secular escapism. Yet Eagle’s discipline holds the project together. His baritone is commanding but never overbearing; his ear for boom‑bap drums and spiritual jazz inflections gives the record a warmth often missing from contemporary trap. Most importantly, his lyrics are not ornament but evidence. Whether he’s recounting unglamorous childhood memories, naming the industries that exploited him, or rustling prayers over his daughter’s head, he makes the personal political and the political personal.

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Lil D.,” “Afro Comb,” “My Daughter’s Hand”