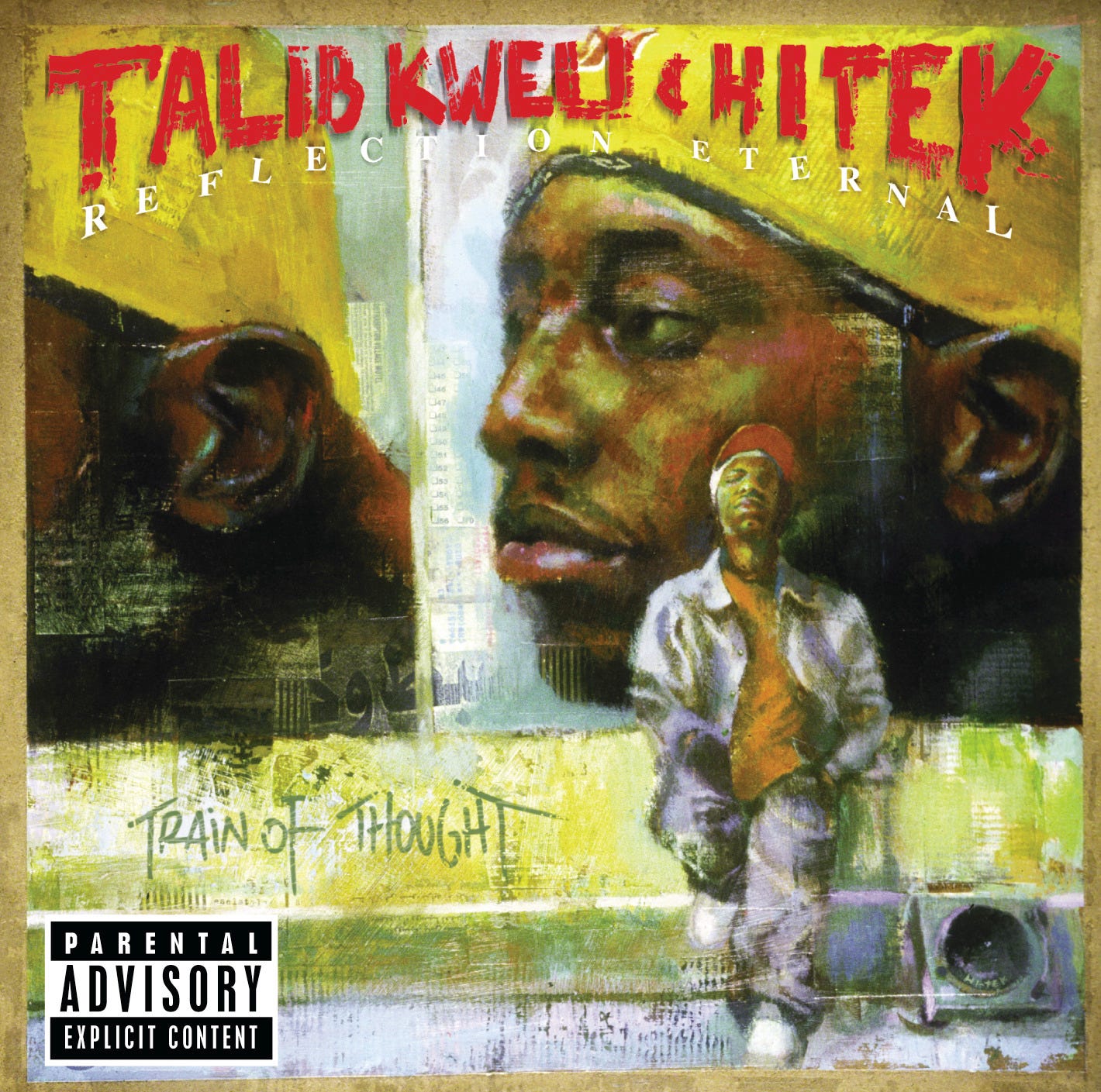

Anniversaries: Train of Thought by Reflection Eternal

Talib Kweli and Hi-Tek’s debut as Reflection Eternal remains a benchmark for collaborative hip-hop albums. This was a train of thought that kept moving, carrying its influence forward.

Rawkus Records was the epicenter of a new underground hip-hop renaissance, and among its rising stars were a Brooklyn emcee named Talib Kweli and a Cincinnati-bred DJ/producer, Tony Cottrell, better known as Hi-Tek. The two first connected through Kweli’s college roommate (a Cincinnati native) and forged a bond in the Midwest scene, collaborating with local group Mood before cutting their own tracks. By 1997, Reflection Eternal—the name of their duo—had released the 12-inch single “Fortified Live” b/w “2000 Seasons” on Rawkus, featuring a then-upstart Mos Def on the A-side. That song’s buzz not only announced Kweli & Hi-Tek as formidable newcomers but also sparked an unexpected detour: Kweli and Mos Def teamed up as Black Star, dropping a now-classic collaborative album in 1998 that put conscious, backpack-era hip-hop back on the map. Black Star’s success could have easily overshadowed Kweli’s partnership with Hi-Tek, but instead, it set the stage. Fans now knew Talib Kweli as a deft lyricist with a message, and expectations mounted for the promised Reflection Eternal full-length. That promise was fulfilled with Train of Thought, the duo’s debut album—a sprawling, soulful opus that, twenty-plus years later, stands as both a time capsule of its moment and a timeless piece of hip-hop art.

From the outset, Train of Thought feels like an artistic statement born of true chemistry. It’s a classic one-MC, one-producer project, the kind of fully realized vision that results when two creatives explore their chemistry in depth. Kweli and Hi-Tek brought out the best in each other; as Kweli himself succinctly put it on wax, “I freak with word power, my man speak with beats.” The album was recorded entirely with Hi-Tek at the boards, giving it a cohesive sound and identity. In later years, Hi-Tek would even compare his role on Train of Thought to RZA’s on Wu-Tang’s debut—crafting a “unique sonic landscape” that flows through every track. For Talib Kweli, Train of Thought was the culmination of his early trajectory: from ripping open-mic cyphers in Washington Square Park to stealing scenes on Rawkus compilations (his solo cuts like “Manifesto” on Lyricist Lounge Vol. 1 and “On Mission” from Soundbombing 2 were underground favorites)—all of which established his reputation as an erudite, passionate MC. That duality—the thinker and the competitor, the old soul and the young firebrand—is all over Train of Thought, giving the album a dynamic tension that still feels electric.

Kweli’s rapping on Train of Thought is often celebrated for its blend of social awareness and personal introspection, delivered in an acrobatic, image-rich flow. The album’s opening salvos, “Move Somethin’” and “Some Kind of Wonderful,” burst out the gate with cipher-tested bravado. Over the “tympanically booming” bass of “Move Somethin’,” Kweli ducks and weaves through punchy battle rhymes, even as he urges listeners to open their minds. “You cats ain’t real, y’all just a reenactment… soon as the director say action, you start fakin’,” he quips, calling out inauthentic rappers with a deft jab. “Some Kind of Wonderful,” in turn, is a dizzying exhibition of what some have called Kweli’s “baroque” rhyme style. He packs words into tight internal rhythms, yet maintains crystal-clear diction and focus. In that track, Kweli unleashes tongue-twisting braggadocio, claiming his lyrical artistry can “blow out filaments and light fixtures” and paint “graphic masterpieces” that leave lesser MCs in shambles. It’s the sound of a young wordsmith reveling in his prowess, challenging any comers, much like a boxer at his peak sparring with shadows.

Yet for all his competitive flair, Kweli’s mature worldview sets him apart from many peers of the era who were defined by more youthful exuberance or nihilistic braggadocio. Train of Thought has plenty of head-nodding energy, but its heart lies in songs where Kweli turns his focus outward and inward with equal insight. “The Blast,” the album’s most iconic single, strikes that balance perfectly. Hi-Tek lays down a laid-back, shimmering keyboard groove—a mellow, melodic backbone that all but glistens—and Talib Kweli uses the warm vibe as a rallying call. In the first verse, he even helps newcomers with the pronunciation of his name (“Tah-lib KWA-lee”), then confidently declares his arrival: “We make the sky crack, feel the fly track/Get your hands up like a hijack.” That is a call to action—not a threat, but an invitation for the audience to participate, to elevate.

The hook, aided by the sweet vocals of Vinia Mojica, turns it into a soulful singalong. “The Blast,” with its infectious call-and-response chorus and Kweli’s articulate, uplifting brags, epitomized what one reviewer called the rare “socially aware hip-hop record that can get fists pumping in a rowdy nightclub.” It proved that being conscious didn’t mean you couldn’t also be cool. Kweli’s delivery throughout the album has this poised intensity—measured and thoughtful, yet never dour. In an era dominated by flashier flows and party anthems, his voice on Train of Thought was like that of an older brother figure: encouraging, wise, but still down to have fun in the cipher. The contrast between his articulate, contemplative tone and the more carefree swagger of some contemporaries only made him more distinctive. It’s a contrast that still resonates; to this day, artists who balance insight with exuberance draw from the blueprint Reflection Eternal helped craft.

Kweli’s social consciousness truly shines on deeper cuts. Take “Good Mourning,” one of the album’s most introspective moments. Over Hi-Tek’s haunting backdrop—built from ghostly keys and vibraphone that echo like a twilight urban skyline—Kweli ruminates on the fragility of life. The song’s title is a play on words; Kweli essentially delivers a eulogy and a wake-up call in one. He contemplates mortality, recalling fallen friends and pondering his own legacy, yet the tone is not defeatist. Instead, it’s life-affirming in its urgency: tomorrow isn’t promised, so do something meaningful today. Likewise, “Too Late” (featuring singer Res, credited as the duo Idle Warship) offers a critique of the rap industry’s direction at the turn of the millennium. Over a slinky beat, Kweli calls out half-hearted artists and poses a provocative question to the culture: “Where were you when hip-hop died? … Is it too late to ride?” It’s a challenge to himself and his peers to rescue hip-hop’s soul before it’s lost for good. This kind of commentary—decrying commercial complacency and urging a return to authenticity—would become a staple of “underground” hip-hop in the 2000s, and Kweli was at the forefront of that movement here, guiding listeners “through the wilderness” and showing them “how to be a man” in the wilderness of cultural corruption. He does it with style and heart, never sounding like he’s simply moralizing.

Perhaps the most powerful display of Talib Kweli’s narrative skill and social insight comes in the album’s finale, “For Women.” Folded into the extended “Expansion Outro,” this song was directly inspired by Nina Simone’s classic “Four Women,” and it finds Kweli picking up that revolutionary soul torch. Across four verses, he inhabits four different characters—four Black women, each with her own harrowing story reflecting facets of the African-American experience. In vivid detail, he explores institutional racism, sexism, colorism, abuse, and inherited trauma, all through the eyes of these women. One verse might tackle a woman scarred by slavery’s legacy, the next a woman battling addiction or exploitation; each story is distinct yet interconnected by the thread of resilience and the quest for dignity. Kweli’s storytelling is compassionate and unflinching, painting portraits that are heartbreaking yet empowering in their visibility. Train of Thought has transformed from a mere album into a fabric of Black life, past and present. It’s a daring, poignant way to close a record—a far cry from the usual “outro” tracks of the era—and it underlines the album’s depth. Kweli concluded his debut album by speaking truth to power in the tradition of Nina Simone, and in doing so, he ensured the album’s impact extended far beyond clever rhymes or head-nodding beats.

Where Talib Kweli’s lyrics and delivery provided the soul of Train of Thought, Hi-Tek’s production was the body that carried it. Over the course of the album, Hi-Tek demonstrates a remarkable evolution and versatility as a producer, all while maintaining a signature sound. His approach on Train of Thought is often described as minimalist yet richly textured—he doesn’t clutter the tracks with excess, opting instead for clean, elegant loops and crisp drum programming, but listen closely and you’ll hear layers of musicality woven in. Hi-Tek was a student of ‘90s boom-bap and soul-jazz grooves, and here he filters that through a refined, almost streamlined aesthetic. The beats feel organic and warm, built from buttery basslines, loping keyboard melodies, and chopped samples of bygone funk and jazz records. The producer’s goal, it seems, was to create a cohesive sonic environment for Kweli’s verses to flourish, and he succeeded. Train of Thought flows with the continuity of a concept album, thanks in large part to the unified mood of the production.

This is not to say the beats are one-note; on the contrary, Hi-Tek flexes a wide range of styles across the 20-track journey. He’s adept at flipping between hard edge and smooth soul. “Down for the Count,” a posse cut featuring Rah Digga and Xzibit, showcases Hi-Tek’s experimental side: he chops the beat with staccato bursts of volume and inserts crunchy guitar riffs between the bars, heightening the sense of competition as each MC tries to outdo the last. (Not to be outdone, Xzibit contributes an “i-rate, using your body for live bait” one-liner that matches the beat’s aggressive flair.) On “This Means You,” a reunion with Mos Def, Hi-Tek sprinkles in string samples that give the track an almost cinematic drama, as if heralding Black Star’s brief return. Then there’s “Ghetto Afterlife,” a song that no one expected going into this album: the legendary Kool G Rap trading verses with Talib Kweli. Generational and stylistic differences aside, Hi-Tek makes it work by digging deep into his bag of New York influences—he laces the track with dusty, “dirty” piano keys and even scratches in the voice of DJ Premier (another legendary producer) as a sampled hook, giving the song a gritty, early-‘90s NYC feel.

The album is also dotted with soulful, mid-tempo grooves that bring out Kweli’s reflective side. “Memories Live” is a standout, built on a lush sample (a gorgeous blend of gentle guitar and a soft vocal hum) that evokes nostalgia. Over this backdrop, Kweli pens an autobiographical ode, looking to the past to guide his present and future—even discussing how reminiscing on his upbringing helps him be a better father to his young son. Hi-Tek’s touch here is subtle; the beat feels like a comfortable armchair, inviting to sit back and absorb the wisdom. “Love Language,” featuring the silky voices of Les Nubians, similarly finds its footing in a mellow, jazz-inflected rhythm. The track has an almost aqueous quality—a fluid bassline, soft conga-like percussion, and shimmering piano loops—as Kweli explores love in its many forms, from romance to brotherhood, concluding that love itself is a form of communication that transcends words. The production mirrors the theme by blending languages (Les Nubians sing in French) and musical textures to create a universal vibe. “Africa Dream” is another moment where Hi-Tek expands the palette: co-produced with jazz pianist Weldon Irvine (a mentor to Kweli), it features live keys, trumpet, and percussion for an Afrocentric jazz-funk feel.

Hi-Tek also isn’t afraid to lighten the mood. After the album's heavy mid-section of social commentary, Train of Thought offers “Touch You,” a playful track that edges into party territory (the closest the album comes to one, as noted by one writer). Over a slinking, funky bassline and misty keyboard chords, a comedic intro unfolds: none other than Dave Chappelle appears, doing a tongue-in-cheek impression of Rick James to set the stage. The track, featuring Cincinnati rapper Piakhan and producer/rapper Supa Dave West on the chorus, is sultry and fun—a reminder that even a “conscious” album can kick back and not take itself too seriously for a few minutes. Moments like these make Train of Thought richly textured in tone as well: it’s not all solemnity and struggle; there are threads of humor, flirtation, and jubilation woven into the fabric. That balance is key to why the album rewards repeat listens and still feels alive. Hi-Tek’s evolution from a regional beatmaker to a producer capable of helming a classic album was fully realized here—his work on Train of Thought earned him equal billing, and rightly so.

At 20 tracks and roughly 70 minutes long, the album is a hefty journey—especially by today’s attention-span standards. Even upon release, some noted that 20 tracks were “quite a lot to chop up,” suggesting the abundance could be daunting for casual listeners. Train of Thought is indeed ambitious in its scope—it was striving to be comprehensive, to say everything Talib Kweli and Hi-Tek had to say at that point in their careers. One might identify a couple of interludes or lesser songs that could have been trimmed (the brief spoken pieces or the low-key “Love Speakeasy” interlude, for example). But to frame the album’s length as a flaw would be to miss the forest for the trees. The expansive runtime allowed Reflection Eternal to cover an impressive thematic and sonic range. The album doesn’t feel padded so much as it feels holistic—it’s an experience meant to be absorbed from start to finish, a true journey of thought with detours into history, philosophy, love, battle raps, and back again. Despite its length, the album flows logically and maintains a consistently high level of quality throughout— the occasional lighter track or extended skit hardly diminishes the impact.

The legacy is increasingly clear. On one hand, it absolutely cemented Talib Kweli and Hi-Tek’s status as fixtures in the hip-hop canon—especially in the realm of conscious, lyrically driven music. Within the hip-hop community, the album is often cited in the same breath as the greats of that era. In the wake of the album, both artists pursued separate projects: Kweli launched a long solo career (his 2002 album, Quality, yielded the Kanye West-produced hit “Get By”), and Hi-Tek released his own acclaimed compilation, Hi-Teknology, in 2001. For a long time, Train of Thought stood as the sole Reflection Eternal album, a one-off gem that fans held onto while the two collaborators explored other paths. It wasn’t until 2010 that Kweli and Hi-Tek reunited for a second Reflection Eternal album (Revolutions Per Minute), and by then Train of Thought had attained a kind of cult-classic status. The follow-up, despite moments of brilliance, “couldn’t deliver upon the promise of longevity as a group” that their debut had suggested. Perhaps too much time had passed, or the chemistry wasn’t the same—whatever the case, Train of Thought remained the duo’s definitive statement. If an artist is lucky, they make one album this impactful in their career—Kweli and Hi-Tek did it on their first try, and that achievement is ingrained.

On the other hand, Train of Thought did get overshadowed in some broader cultural sense, though not through any fault of its own. The late ’90s and early 2000s were a whirlwind time for hip-hop, with multiple classics dropping in succession. Black Star’s album (1998) was a landmark that introduced Kweli to new fans; Mos Def’s Black on Both Sides (1999) then became a breakthrough moment for conscious rap in the mainstream, perhaps drawing more attention at the time. When Train of Thought arrived in late 2000, Rawkus Records’ wave was at its peak—yet the very next year saw the underground scene start to fracture (Rawkus would soon disband, and the industry was shifting). Kweli’s subsequent projects, such as Quality (2002) and the single “Get By,” arguably reached a wider audience than Train of Thought did, which means that in popular memory, Talib Kweli might be more immediately associated with those later hits or with Black Star than with the Reflection Eternal album. Similarly, Hi-Tek’s production notoriety grew as he worked with artists like 50 Cent, The Game, and others in the mid-2000s; younger fans might know his beats without necessarily tracing them back to Train of Thought.

Talib Kweli and Hi-Tek’s debut as Reflection Eternal remains a benchmark for collaborative hip-hop albums. It’s the kind of record that artists cite as influential, even if it never dominated charts. It proved that a rapper renowned for “lyrical, spiritual, miracle” verbosity could tighten up his craft into structured songs that still bumped in the car. It proved that a DJ from Cincinnati could create a sonic world as vibrant and soulful as any New York veteran. And it proved that hip-hop albums could be conscious and cool, personal and broadly appealing, all at once. Two decades on, listening to Train of Thought is like hopping on a time machine that somehow still knows exactly where we are today. The urgent call of “The Blast” can still get a crowd amped. The heartfelt words of “Love Language” and “For Women” (long before he got run off from Twitter because of attacking Black women) still educate and resonate amid ongoing conversations about love, gender, and race. The album’s title feels prophetic: this was a train of thought that kept moving, carrying its influence forward. As the Reflection Eternal moniker implies, the ideas and vibes here are timeless, echoing without end.

This, to this day, is one of my faves. Definitely a start-to-finish, no skips listen.