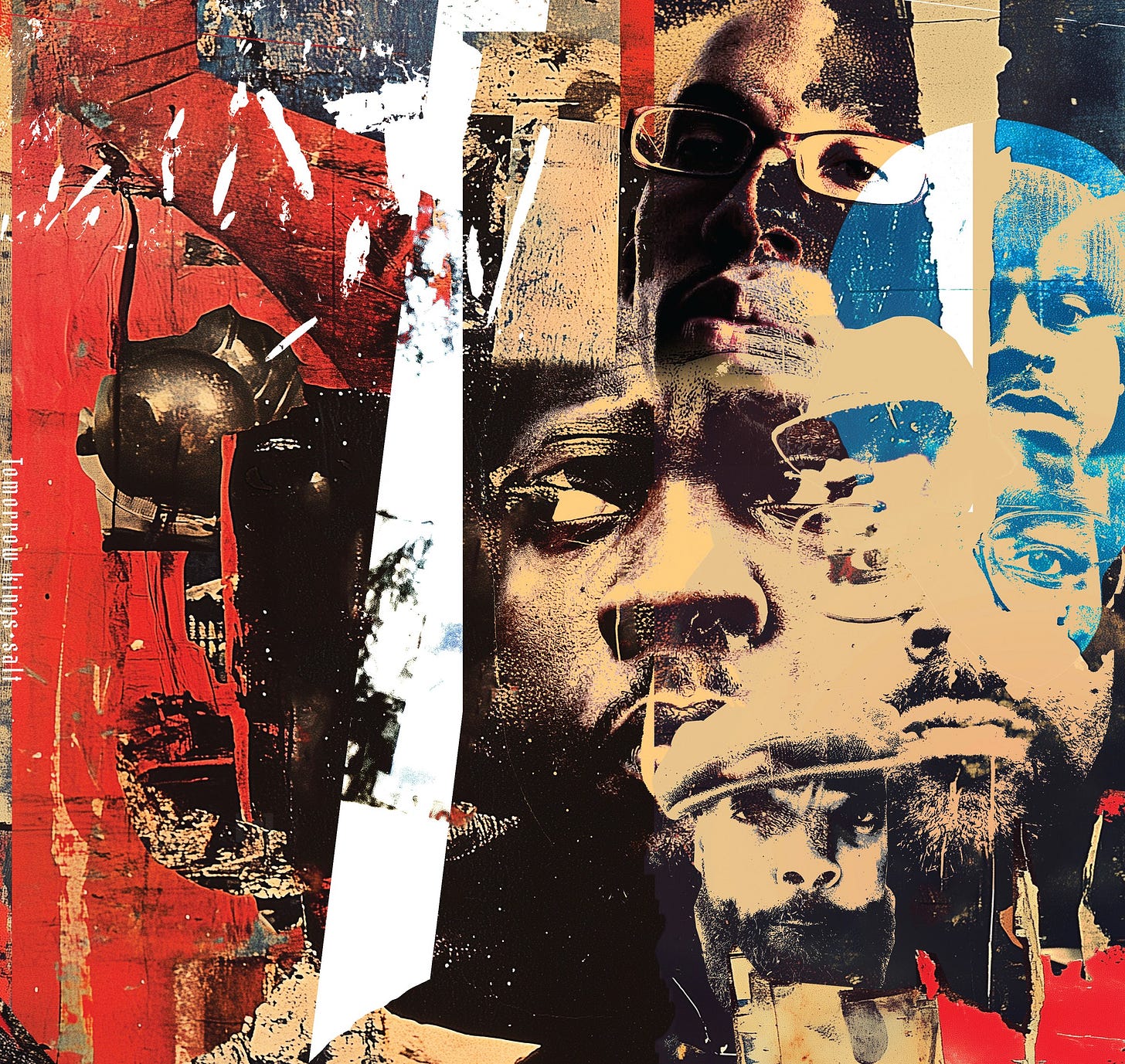

Album Review: SALT by Tomorrow Kings

A decade out of sight hasn’t dulled Tomorrow Kings’ edge—it’s honed it into something sharper. SALT is the sound of a collective refusing extinction, turning exhaustion and intellect into survival.

Where most rap groups dissolve into solo projects or fade away, Chicago’s Tomorrow Kings have spent nearly two decades constructing a mythos out of persistence. They formed in 2007 and released their debut Niggers Rigged Time Machine in 2013; twelve years later, SALT is their first unified release in more than a decade, a record born in quarantine and arranged through traded files and late‑night emails. The collective—now trimmed to six core MCs—has matured into parents, community members, as artists, and that shift is corporeal. SALT isn’t a bid for mainstream validation so much as a mirror. The record sets out to crystallize a philosophy the crew has been forging in the margins, one that treats survival as art and history as a weapon.

SALT opens with “Regicide,” and with it a voice, Collasoul Structure’s daughter Ava, recorded when she was four, singing, “This world will never end,” an eerie lullaby that frames the album’s central question. The song explodes into a serrated ensemble piece; each MC brandishes a different blade, but they strike in unison against inherited hierarchies. Collasoul sets the pace with a “cold brew coffee to heart” and a “kick in the chest anthem.” He swings at whiteness with “fuck that cracker shit… wasting lines on the pale and tasteless makes me wanna scratch and sniff,” mixing humor with venom. Gilead 7 inverts martial arts clichés—“Roundhouse versus crane kicking/Brute force vs brain picking”—while Malakh El flips mysticism into defiance: “Full lotus position, laser focus, and a resistant disposition.” For the moment Skech185 arrives, his verse is a Malevolent Shrine all its own: “Between false idols and legends dead in a web of red tape/Your last stand was a crater with death dancing like Gator.” When he declares, “Regicide: when racism tries hide homicide,” the word becomes an anti‑imperial sermon, not just a clever rhyme. The track functions as a thesis statement: kill the kings (literal or symbolic) and build a new order.

The production across SALT is as varied as the voices rapping over it. Aoi’s beats feel like Chicago itself—dust‑heavy drums, chopped horns, sirens wailing in the distance. There are definitely moments where the percussion stumbles like an elevated train car hitting rusted tracks, while the synths flicker like faulty street lamps. There’s no fetishistic gear talk here because what matters here is texture. These are post‑industrial soundscapes, built for voices that do not trust smooth surfaces. Jazz occasionally bursts through the grit, a melodic exhale that conjures the collective’s live improvisational energy. When the record leans into atmosphere, it’s not because the crew has softened—it’s because they know that ambience can smuggle in anger more subtly than constant bludgeoning.

Two long‑time fans debate the record over coffee. One marvels at how Tomorrow Kings have transformed survival into poetics, and the other wonders whether the record is endurance art or a communion. “Red Summer” gets under their skin for good reason. I.B. Fokuz opens by contextualizing Chicago’s 1919 race riot, counting “1–9–1–9 crossing that imaginary line/One stone can make a dead man float in a glass wine.” He prays to break locks and open mansions, admitting that “I had a thought of murder just to cope, to push the bandwidth.” Collasoul Structure answers with a surreal snapshot of racism’s banal disguises—“white man from town got my patience lil thinner… they threw our babies to the gators you remember?”—linking historical atrocities with contemporary microaggressions. Skech185 delivers an indictment of respectability politics: “There’s a sniper trained on your ‘safe space,’ atop a church… how long do you think you will last after giving these crackers maps to your pressure points?” The refrain (“I’ve seen my city burn/Burn to the ground… all I see is death/Red summer all around”) is a lament and a warning. The song is not simply a history lesson. It’s a dispatch from within a continuum of violence that loops 1919 into 2020.

Because SALT was written and recorded during the isolation of 2020, it carries a claustrophobic weight, but it refuses to collapse inward. “The News” dissects media consumption with scathing precision. IL. Subliminal opens with a mock‑broadcast: “We now interrupt your regularly scheduled programming of gratuitous violence and pornographic slow jamming.” His wordplay is playful( “Steakhouse Arson Outback Requestin Live… Totalitarian Shows Tonight shot vaccine”), yet the absurdity highlights how mundane cruelty has become. Skech185 enters with a different tone: “I wasn’t posted on the block, dummy. Why would I do that? They’re out there shooting niggas. Comic books don’t shoot Blacks.” He recounts walking past the spot where his uncle was shot en route to school, then contrasts his own muted graduation celebration with the jubilant welcome of a cousin returning from prison. The track reduces broadcast to its elements: “Murder, weather, sports,” a grim mantra that makes clear how often Black deaths are slotted between traffic and basketball scores. There is humor here—“Old ruthless style tribunal/Times Roman sun readers obituary funeral/Funny paper wise StreetWalls plaster urinals”), but it is a laughter that knows what is at stake.

Unlike albums that treat the working class as a demographic to be pandered to, Tomorrow Kings write from within those fatigues. “B‑Side Losers” is arranged by a resigned intone, saying, “It’s an uphill climb all the time… maybe next lifetime you can have dope rhymes.” Collasoul Structure lays out his ambition plainly: “I just wanna feed my daughter wit’ this rap money, kill her mommy’s stress.” His economic frustration is discernible—“I’m burned out, I’ll be working all my life just like my father said… turns out, I’ve been working all my life just like my father did”—yet he never reduces himself to victimhood. Gilead 7 veers into dark surrealism, describing a suicide in an art gallery: “I took my life in the rear bathroom… floating above the corpse I smile at the talking scars.” He confesses the dream of being a writer with an album budget built on overtime, and the sinking suspicion that “it’s looking like this is a waste of life and my heart should embrace the knife.” The verse is harrowing but not indulgent; it captures how financial precarity and creative aspiration can conspire to lead to self‑destruction. D2G, one of the guest MCs, extends the analysis, pointing out how success stories become rare exceptions used to justify systemic neglect: “Seems like outside of those, successful stories they can fascinate… but rather offer options to educate, they eradicate.” When he ends with a scream—“Nobody likes rockin’ the suits when it’s casket apparel, FUCKA!!!!”—it lands like a final straw.

The title track, “Salt,” is perhaps the most direct example of the album’s philosophy. IL. Subliminal reduces language to its elements (“Salt/salty/saltine/assaulting/iodized/crystallized”) before expanding into a metaphor. “Salt and sugar the same to naked eyes… What if salt be stress and sugar be self-soothing?” he asks. The metaphors multiply: processed cocoa leaf becomes sugar and cocaine, salt becomes a substance used to mask the smell of dead flesh, diabetes and hypertension kill as many people as the Ku Klux Klan, police, and Reaganomics combined. Salt, in this worldview, is both a preservative and a poison, a necessary mineral and a metaphor for the injuries Black bodies absorb. The final series of questions, “What are we digesting, what are we swallowing?/What are we wallowing in?” drives the point home. It’s rare to hear a song about diet, addiction, and structural violence without sounding preachy. IL. Subliminal instead builds a collage of images that invites interpretation. His delivery is layered, breathless, fiercely intelligent yet unpretentious, which epitomizes the group’s essence.

Part of what makes Tomorrow Kings compelling is that each member brings a distinct worldview. Collasoul Structure, as the group’s most grounded voice, often speaks from lived experience. His verse on “B‑Side Losers” about wanting to feed his daughter evokes a realism that anchors the group’s more abstract flights. I.B. Fokuz is the moral compass; his exhaustion is audible when he notes on “Red Summer” that Chicago riots off real estate and calligraphy, describing the city as a ticking time bomb. On “The News,” he warns that a pillar of salt is “only a nigga that’s lost”; this biblical inversion reveals his suspicion of nostalgia. Skech185 is the group’s apocalyptic satirist. Whether referencing the mundane—“Comic books don’t shoot Blacks”—or the arcane—Oppenheimer’s thoughts on the problem of the atom—his bars twist between tragedy and sarcasm.

Gilead 7 leans toward theological abstraction; his lines on “Regicide” about breaking hour glasses and passing the formless drink to Kairos hint at a cosmic time frame, while his suicide vignette in “B‑Side Losers” enters metaphysical territory. IL. Subliminal balances fatal humor with sincerity—“I ain’t got shit to prove… we don’t compete/We complete the DOOM”—but he is also the one who constructs the album’s central metaphor. Malakh El brings mysticism and militant energy, punching out lines like “My pen is ill in any dimension… fake shit is the reason I foul flagrant”. Together, the MCs form an organism wrestling with Black futurity and fatigue, each representing a facet of survival: realism, exhaustion, satire, abstraction, humor, and mysticism.

Throughout the record, the central metaphor of salt reappears, not just on the title track. I.B. Fokuz flips the biblical story of Lot’s wife into modern commentary: “a pillar of salt is only a nigga that’s lost.” When one conversation partner asks whether art like this is worth the emotional toll, the other quotes IL. Subliminal: “Too much of anything can put you in the emergency room.” That applies to salt, sugar, grief, and even activism. The pressure on Black creativity is to soothe and diagnose simultaneously; to provide catharsis without offering escape. Tomorrow Kings answer that pressure by refusing to make easy consumption. They compress centuries into four‑minute bursts and trust listeners to keep up. The record doesn’t ask permission to be difficult. It demands that the world stop salting the wound so the body can heal.

As the discussion winds down, both fans agree that SALT feels less like a comeback than a continuation. Since their debut, the collective’s tone has shifted: there is less youthful braggadocio and more parental urgency. The Chicago Magazine piece on them notes that during the debut era, only I.B. Fokuz was a father, whereas by SALT, many members are parents. That maturity is audible. The crew still wield references with wild abandon, but there is an underlying clarity: songs like “B‑Side Losers” and “Salt” are built as working documents for how to survive capitalism and structural racism. Their goal is not to appear clever, though they often are, but to articulate a philosophy of endurance. SALT is, above all, a communion. For the day ones, this record is about those who have followed their myth‑making in the underground to step into a conversation, to nod along not just to the beats but to the arguments embedded in them.

Granted, its density occasionally overwhelms, and some tangents feel indulgent. Yet these minor missteps are outweighed by the album’s ambitious scope, the depth of its songwriting, and the cohesion achieved despite the crew’s geographic and temporal distance. Tomorrow Kings reaffirm why they remain crucial to progressive rap: their ability to convert survival into poetics and to treat history as both mirror and weapon.

Standout (★★★★½)

Favorite Track(s): “Regicide,” “Red Summer,” “B-Side Losers,” “The News”