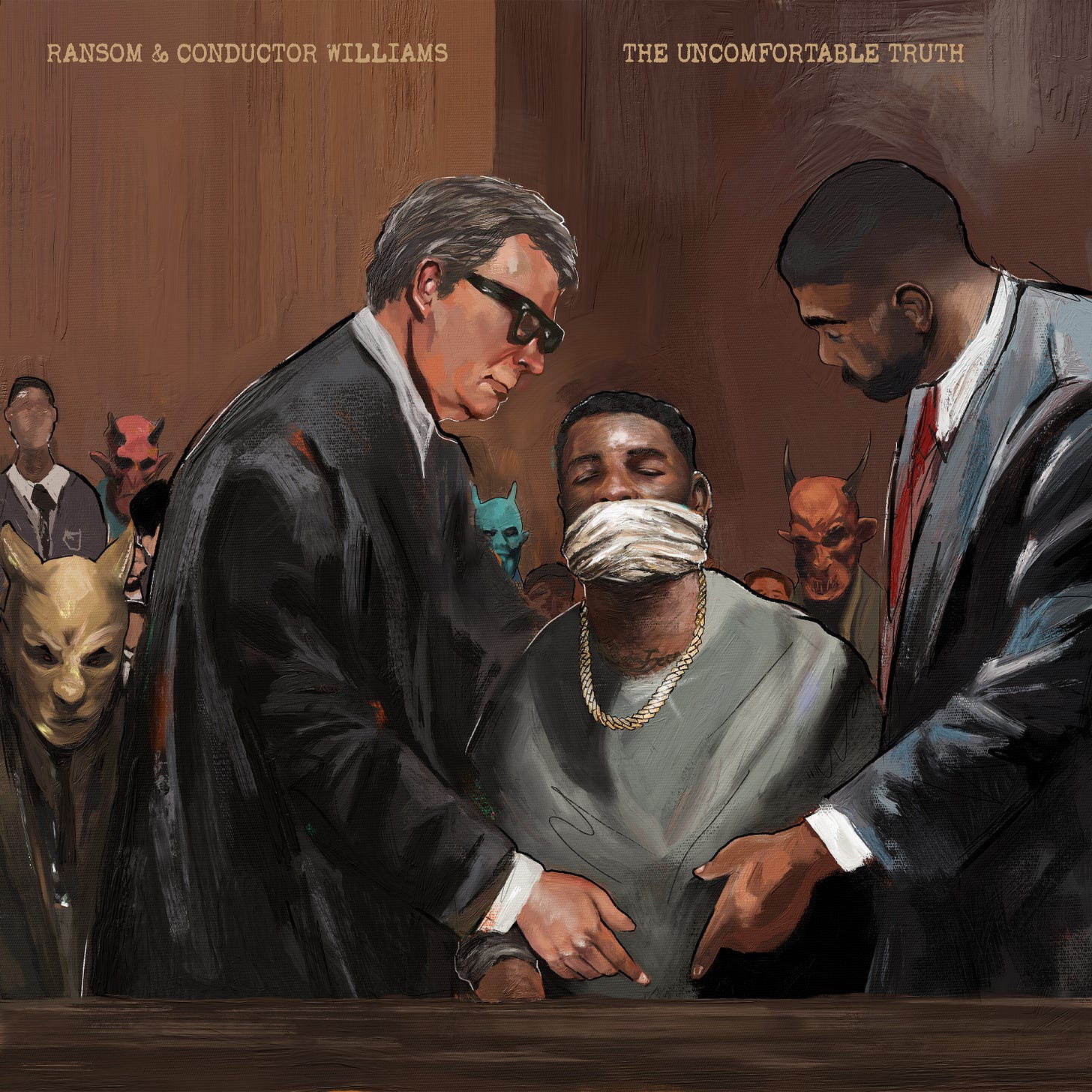

Album Review: The Uncomfortable Truth by Ransom & Conductor Williams

Ransom has never been a comfortable rapper, but his collaboration with Premier gave him a new dimension. Now joining forces with Conductor Williams, he pushes into his own misgivings.

Much of Ransom’s appeal has always been the grain of his voice and the way his writing cuts into his own legend. Over two decades, he went from street rapper to a collaborator with producers like Nicholas Craven and Big Ghost Ltd, and Premier’s Reinvention was a high‑profile reset. The new set keeps the focus on that evolution. There’s still bravado, but the tone is tired and suspicious rather than triumphant. In “Clairvoyance,” he starts by mocking the emptiness he sees around him: he calls out the “little drought in your content” and questions who really is “the best” over a Conductor loop that feels like it’s barely moving. Rather than rattling off punchlines, he ticks through names—Jay, Nas, B.I.G., 3 Stacks, Scarface, T.I.—only to pull the conversation back to his own class. The hook, with its exhausted “Are you not entertained?/Feel every drop full of pain,” announces a man who’s done performing for applause and expects us to sit with his pain. Conductor’s production leans on murky pads and bouncy trap drums, giving Ransom room to switch his cadences; he sounds measured where he once barreled through beats.

That patience suits the way he writes about expectation. The Uncomfortable Truth spends little time on wide‑angle analysis and instead mines his own contradictions. “Blood Stains on Coliseum Floors” mounts his ambition as an arena fight he never asked for. He raps, “I’m not a team player, I’m MJ, never swinging a rock” and lists what he isn’t—no Pan‑African speaker in tight linen, not a drugged‑up rapper, not a vengeful villain. It reads like a dictum from someone exhausted by categories. The beat builds around a warped soul loop that feels like an echo in a cavern; Ransom’s use of “blood stains on the coliseum floors” is about the cost of performing in public. The posture is less about boasting than about defining boundaries: he’s telling his audience what he refuses to be labeled as, and the repetition underscores how often those labels have been thrown at him over the years.

Elsewhere, ego is deployed as armor. “Bomaye” echoes the Muhammad Ali chant but uses it to stamp his own name—Ransom, bomaye. The Conductor beat is more propulsive here, with percussion that kicks up like a march. Ransom uses that momentum to flex (“On this pedestal I’m second to none”) and to taunt copycats (“I say half because you almost eight/But almost don’t count ‘cause half y’all bite”). The braggadocio is familiar, but the edge comes from how he constantly interrupts himself with mortality. Lines about playing dominoes in Monaco and wearing “elegant fabrics” sit alongside warnings that sleep is the cousin of death. The production keeps the tension high; when he shouts his name, it feels like a dare. If anything, the track slips when it falls back on generic punchlines, but the bruised energy carries it.

The album’s midsection turns inward. “Late Replies” is one of the strongest pieces here, a text‑message apology extended into an essay about betrayed friendships. Over a sorrowful loop, Ransom admits he didn’t send the messages because he hates goodbyes. He confesses to cutting the grass before snakes could arrive and writes from a place of regret rather than triumph. Conductor leaves space, and the songwriting leans on plain statements (“This doesn’t mean we’re enemies”) instead of coded metaphors. In the second verse, he gets specific about who is dead to him—someone who blamed their lack of money on white supremacy—and he mocks that excuse with a bitterness that shows how deeply he takes betrayal. The hook repeats his apology, but it’s the details—wishing for friends who hold flashlights when the road is dark—that make the song land. This is not an artist hiding behind cool, and Conductor’s restrained production allows the vulnerability to register. The only stumble is a tendency to over‑explain, as some lines about snakes and grass feel like familiar hip‑hop parlance, even if the emotion behind them is sincere.

Conductor Williams’ influence shows most clearly in how he paces the record. His beats refuse the cinematic builds of Ransom’s earlier collaborations with Nicholas Craven or Harry Fraud. “The Human Animal” is built around low‑end murmurs and a sample that scrapes like a knife. Ransom paints street scenes in blunt strokes with crack‑reeking backstreets, children buying candy with broken teeth, a friend switching over six grand and dying for it. He writes about racing against death without turning his pain into spectacle. There’s a striking moment when he notes, “Same niggas you stand with, you’ll be lucky later to withstand”; the wording is plain, but the weight is heavy. Conductor matches this with a beat that doesn’t evolve, so the verses feel like they’re always leaning forward. It’s here that the partnership locks in: the production doesn’t compete with the storytelling, and Ransom pulls imagery rather than metaphors. Suppose he indulges in a couple of overdone predator‑prey punchlines. In that case, they’re redeemed by “We in a race against death and you tryin’ to pass batons/Flash the arm, send your location and get your addy bombed,” which turns common bravado into a threat about mortality and surveillance.

The theme of loss reaches its most potent point on “Flowers & Tombstones.” J. Arrr opens by pointing out how everyone becomes sentimental after death, noting that the same people who never lifted a finger suddenly post tributes. He calls out the performative grief that follows a rapper’s death: “Another rapper dies and now his streams on the Uber/Need my flowers while I’m walking.” Ransom’s verse takes that further by imagining seeing his own funeral. He tries to “factor the numerals, subtracting all of the few boo‑hoos,” then arrives at a blunt assessment: you’ve been reduced to “an Instagram post and some content for them to use.” The bitterness isn’t romanticized. He’s angry that his life could be reduced to analytics. Conductor’s beat here is haunting and minimal, letting every syllable hang. The song exposes how even grief can be commodified. If the concept feels a bit long, the clarity with which Ransom names the transaction—likes over life—makes the track one of the album’s emotional peaks.

For all the introspection, Ransom still enjoys flexing his pen. “Temple Run,” featuring Kelly Moonstone and J. Arrr, uses the video game title as a loose frame for perseverance. Kelly’s hook about exponential growth and running like she was presidential sets up verses about ambition. J. Arrr wrestles with the cost of fame, noting that a contested three is more appealing than a pass, and later admits he flinched and wasted time settling. Ransom enters as “the new Da Vinci,” aiming for Howard Hughes heights, but he brags about being the best so often that it starts to sound like he’s convincing himself. The production glides, but the song doesn’t cut as deeply as the others. It’s serviceable, buoyed by Kelly’s melodic hook, but Ransom’s verse is more chest‑thumping than soul‑searching. Compared to the vulnerability of “Late Replies,” his boasts here feel perfunctory.

“Trigger or Trigga” closes the set in a different register. The first verse is deliberately provocative, where Ransom claims to drink the blood of an ancient scholar and snort the remains of a famous author. He rails against “white supremacy” and invites enemies to “come risk your family for the sake of honor”. The production is frantic, and a skit at the end reenacts someone crying that racial slurs have been used against them. In the second verse, Ransom turns the premise on its head, describing shoot‑outs where an adjective and a pronoun hit him and ends up in the hospital with a diagnosis of “victimism.” The satire is clear. He’s mocking the idea that words have the same impact as bullets. The concept is clever, but the execution is heavy‑handed. “Heil Hitler, you dumb nigger, that’s live chatter” gets a reaction but lacks nuance, and the repeated insults drown out the point. The idea of weaponized language deserves more precision than a string of shock lines. Even so, the attempt to wrestle with victimhood and offense fits the album’s larger theme of discomfort.

Ransom raps about responsibility—teaching game requires class, leading men is like art in a mausoleum—and then undercuts his own authority with petty jabs. He projects self‑importance, calling himself “Black Hemingway,” then confesses how lonely he is when old friends drift away. He grieves the shallow way death is memorialised and still chases the validation of being chanted at like a prizefighter. This contradiction is the uncomfortable truth promised by the title, aka a man who built his career on toughness now confronting vulnerability and finding that he’s still wired to compete. Conductor Williams recognizes the complexity and keeps the music restrained, letting Ransom’s words carry the weight. When the beats do surge, it’s to push him, not to lift him.

Favorite Track(s): “Clairvoyance,” “Late Replies,” “Flowers & Tombstones”