Album Review: To Whom This May Concern by Jill Scott

After a decade without a studio album, Jill Scott returns with blunt satire, ancestor worship, and sex instructions in the same breath, even when it asks too much of your afternoon.

More than ten years without a new studio album from a singer-songwriter who spent the 2000s rewriting what commercial R&B could sound like is a strange kind of public experiment. Fans age, tastes mutate, and the industry moves its furniture around. Between Woman in 2015 and now, Jill Scott toured anniversary shows for her debut, guested on records by Conway, Kehlani, Teyana Taylor, and Alicia Keys, appeared on Abbott Elementary, and stayed visible enough that people never stopped asking when. She turned fifty-three last April. The question hanging over To Whom This May Concern was never whether she could still sing. The question was whether the new material would weigh what actual need weighs or just fill the space that obligation carved out.

Most of it does. The album burns through its first quarter on a self-authorization streak, from the manifesto talk of “Dope Shit” (where collaborator and poet Maha Adachi Earth sets the temperature with lines about hunger and appetite) into “Be Great,” where Trombone Shorty’s horns push behind a woman naming exactly where she puts her time, how she refuses to be steered by other people’s scorecards, why she is finished begging for clearance to enjoy her own life.

“I doubled down on believin’

That the opinions of other people

Couldn’t light my light

Nor deter my sight

Nor wrong my rights.”

The affirmation genre is crowded in 2026. Scott anchors hers in the particular exhaustion of having earned the right to say it late.

But the record’s strongest instinct is communal. “Beautiful People,” the lead single, praises collective love while calling out “algorithms and wicked, wicked systems of things” by name, pairing Valentine sentiment with institutional suspicion and somehow sounding neither preachy nor naive. “Offdaback” goes deeper, reciting ancestors by first and last name (Sis Hattie, Annie Laurie, Shirley Delores, Linwood Harry, Annie Pitt, Warren Braswell) and connecting their risk to her ability to walk into a bookstore and buy a book, travel the world, or sing to a mixed crowd. She credits Marian Anderson, Nina Simone, Ella Fitzgerald, Billie Holiday, Sarah Vaughan, Tina Turner, and Frankie Beverly without making the roll call feel performative. Each name earns its parenthetical reverence, structured around the specific freedoms those women purchased with their bodies and reputations.

Two of the most telling pieces on the album sit back-to-back and do opposite things with anger. “Disclaimer” is a spoken-word bit where Scott warns that if you sing along and somebody stomps you out, she bears “zero accountability.” The humor is broad, filthy, exaggerated on purpose. She is staking territorial claim over the rest of the record. Then “Pay U on Tuesday” drops the jokes entirely. She is tired of what she calls “nigga blues,” and she inventories the pattern with specific grievances. How do you take a trip and skip your mortgage? You’re in jail again this weekend? You don’t have your child support? You bought a dress when your house is filthy? She means men and women both, and the track clarifies that up front. The word “nigga” here is diagnostic, not slang. She is naming a behavioral cycle (scamming, pretending, lying) and refusing to bankroll it with her patience anymore.

North Philadelphia gets its own flag planted in DJ Premier-produced “Norf Side.” Scott raps with the swagger of somebody defending her neighborhood and her solitude in the same verse, calling out the Instagram commentary about her body, the Illuminati whispers, the people who vanish when she writes or parents or stacks her money. “None of them could ever be me,” she says, then spells her name out loud, daring you to keep talking. Tierra Whack enters on a parallel wavelength, chewing through punchlines about Ms. Lauryn Hill, loaded potatoes, and hoagies with a cadence that’s quicker and sharper but weighted with the same hometown pride. Two women from the same city, separated by a generation, both insisting on their own supremacy. The track holds both claims without choosing a winner.

The ugliest and the funniest ideas on the album often share a verse. “BPOTY” (Biggest Pimp of the Year) addresses a preacher extracting money from his congregation, the pharmaceutical industry keeping patients on subscriptions, and then invites Too $hort to explain the pimp mentality in his own vernacular. $hort’s verse is intentionally repulsive, bragging about manipulation and financial extraction with zero irony. Systems that drain people for profit dress themselves in different costumes (pulpit robes, lab coats, gators) and the mechanics stay identical. “Me 4” is quieter, crueler. A man confessing his own mistakes. Married the wrong person, moved too fast, ignored his instincts, ended up baby mama number four.

“You don’t think it could happen to you, anything’s possible.”

Scott writes his voice with real sympathy, but the compassion coexists with a firm refusal to sentimentalize. He has to stop doing the same dumb thing, and she repeats that phrase until it crosses from advice into begging. Seige Monstracity is another producer to borrow from Birdman’s “What Happened to That Boy” drum loop, which Doechii already used to kick off 2026.

Then there’s “The Math,” which might be the album’s sneakiest piece. It opens with questions in the second person. Could it be we buy dreams to hide what we lack? Could it be we wreck love since it wounded us before? Could it be our ugliness is our favorite bad habit? And then it shifts into physical instruction, telling you to subtract the fake from the real, multiply kindness and harmony, and check your own breathing. The verbs are literal. She wants you to do arithmetic on your own habits, and the directness is disarming precisely because self-help vocabulary almost never commits to actual commands.

“Pressha” sits at the album’s emotional center and might be its quietest devastation. A man chased her for years, she said yes, and then he hid her. “I wasn’t the aesthetic,” she sings, and that phrase cuts with its literalness. Somebody loved her in private and chose a different image for public consumption. She concedes she understands the pressure to appear a certain way, but she also calls it pathetic, and the piece cycles through those two feelings without settling on one. “You’re like the wolf outside my bedroom door/Howling at the moon for me.” The regret belongs to him. The wound still belongs to her.

The record handles love and sex with adult patience. “A Universe” describes falling for someone after she had shut down her romantic life entirely. “I blocked all my incoming calls/Nobody could get close to me/I refused to care at all.” The word “vetted” sitting inside a love ballad is the whole portrait: not twenty-two and breathless, but middle-aged and cautious, ambushed by genuine connection after self-imposed exile. “Liftin’ Me Up” strips the boldness further with a Go-Go backdrop from Dwayne Wright and Eric Wortham.

“I smile, but I get discouraged sometimes

In the back, back corner of my aching mind.”

She compares this person’s love to aloe on a cut, a small functional image that avoids grandiosity, and the tenderness rests on admitting that strength runs out. “Don’t Play” refuses to be coy about sex. She tells her partner to change positions, give her Afrobeats, and please her “hard like a K-Dot lyric, then sweet like my grandma’s yams with the marshmallows on top.” Sexual intensity compared to Kendrick Lamar bars and Thanksgiving dessert in the same sentence. “I ain’t no city street,” she warns. “I’m a grown wonder woman, alive and free.”

JID’s feature on “To B Honest” earns its placement by exposing a gap. Scott’s verses are plain-spoken, almost pastoral. She wants to hold a person close, to know them, to be their friend. “Won’t you please let me in?” JID arrives on a current of ornate imagery (hummingbirds, blossoms, pollen, parables) and his decorative style sharpens by contrast how much emotional weight bare words can bear when the person speaking them means each one without ornament.

“Ode to Nikki,” with Ab-Soul, reaches for the cosmic and occasionally trips over its own ambition. Scott poetically writes about escaping perpetual loops, tasting your own vibrancy, crumbling cages. Ab-Soul pulls in sacred geometry references (Metatron’s cube, titanium backbones, solar orbits). The diction is dense, and some of the spiritual shorthand collapses into abstraction. But the aim is to name what it takes to stop being trapped by old patterns, and the urgency compensates for the occasional opacity. “Right Here Right Now” and “Àṣẹ” close the prayerful wing, collapsing “àṣẹ” and “amen” into interchangeable blessings and mapping gratitude onto the body (wiggling toes in the rain, hands in the air, health from tip to toe). “Sincerely Do” is the final letter. “I called so many times/Not from my cell, though/I been reaching out from my heart and soul.” The distinction between spiritual contact and technological contact houses the album’s whole philosophy of correspondence. The letters on this record were never meant for mailboxes.

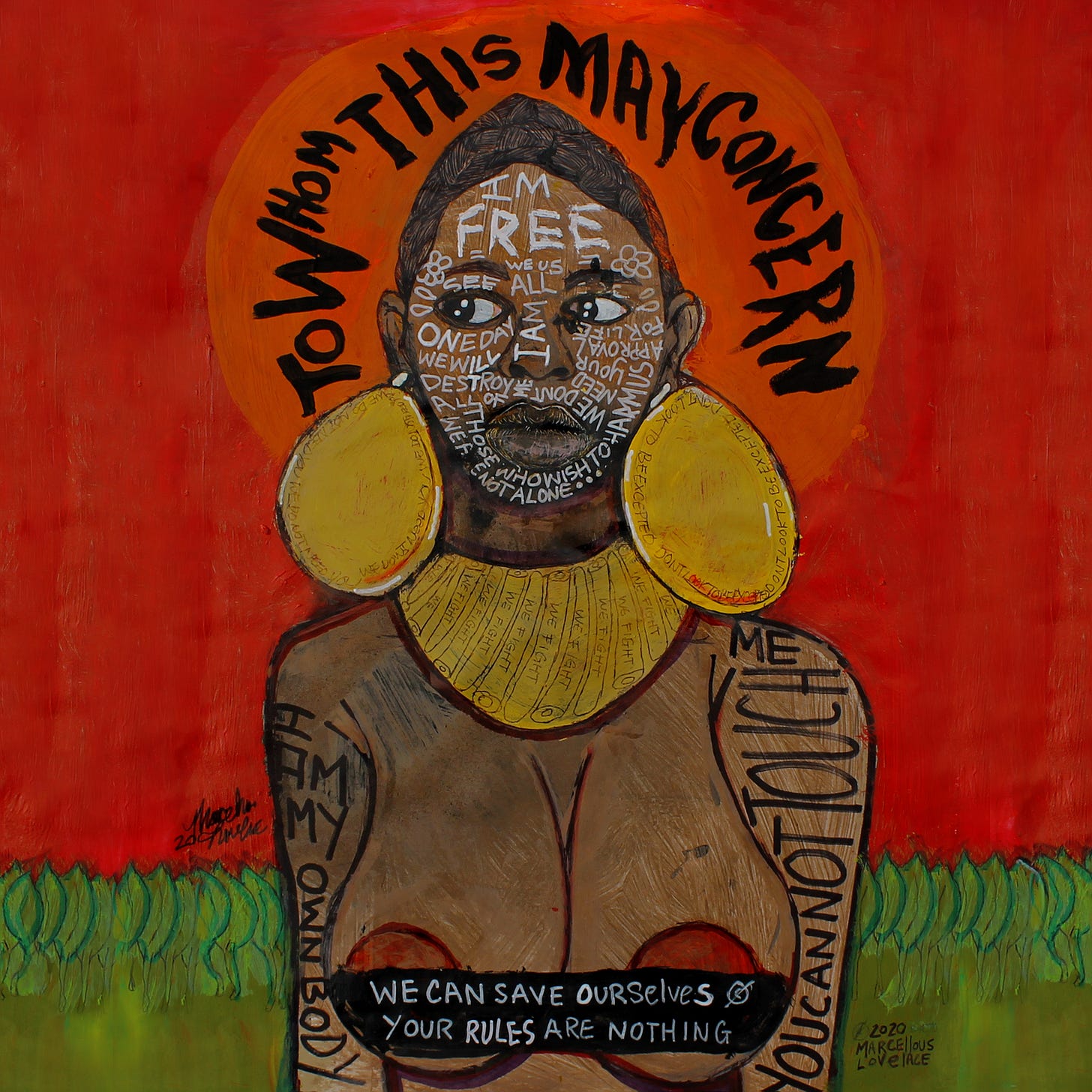

The cover art, painted by Chicago artist Marcellous Lovelace, depicts a nude Black woman wearing a collar inscribed with “We fight.” Declarations surround her (“We can save ourselves,” “Your rules are nothing”) and that defiant, tender visual maps onto what the album spends nineteen tracks doing. Scott is writing to lovers and haters and ancestors and the city and herself and whoever is listening, and the writing stays grounded in real behavior. She names mortgages and jail and child support and aloe vera and grandma’s yams and blocked phone calls and DJ Premier and Metatron’s cube. The specificity is the craft. The calligraphy across the album’s many modes (manifesto, communal hymn, profane satire, bedroom talk, spiritual petition) maintains a remarkably consistent voice. The best moments here are a woman who spent a decade collecting things she needed to say and found that nearly all of them still mattered because it’s so Black!

Great (★★★★☆)

Favorite Track(s): “Norf Side,” “Pay U on Tuesday,” “BPOTY”