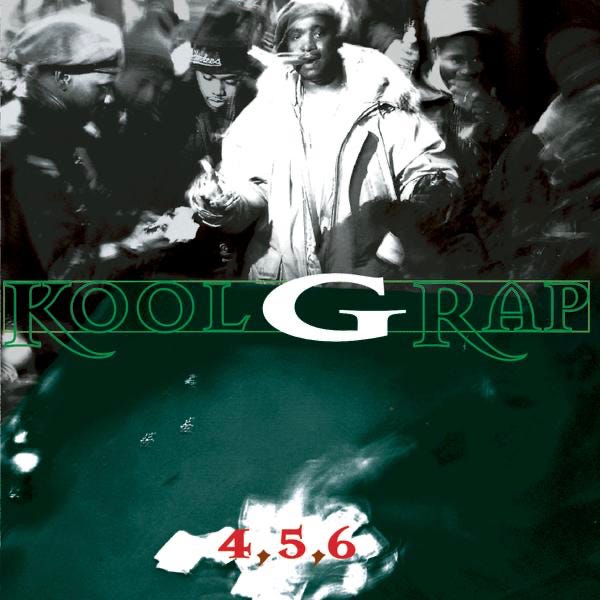

Anniversaries: 4, 5, 6 by Kool G Rap

As long as rap fans value lyrical virtuosity and authentic storytelling, the legacy of 4, 5, 6 will continue to grow, calling for the kind of respect and reexamination that true classics command.

Amid personal turmoil and industry upheaval, Kool G Rap rolled the dice on a new chapter. His debut solo album 4, 5, 6—now over a quarter-century old—emerged as a hip-hop noir, steeped in the shadows of its creator’s Bronx-to-Queens heritage and the Juice Crew legacy that birthed him. A protégé of Marley Marl’s famed Juice Crew collective in the late ’80s, G Rap had already cemented his status as an MC’s MC, influencing everyone from Nas and Biggie to JAY-Z, Tupac and the Wu-Tang Clan with his rapid-fire street narratives But 4,5,6 was something different: a solo venture forged in isolation and danger, carrying the weight of both an era’s collapse and a new, somber vision of New York’s underworld. It stands today as a dark, underappreciated classic – the final salvo of Cold Chillin’ Records, a showcase of Kool G Rap’s uncompromising storytelling and mood-setting, and a blueprint that would resonate through hip-hop’s next generations.

The album’s creation was anything but smooth. Three years prior, Kool G Rap (Nathaniel Wilson) and his DJ partner Polo had released Live and Let Die (1992), a brilliantly vicious record mired in controversy. The album’s original cover art—reportedly depicting two mobster-hit cops hanging from ropes—proved too extreme in the wake of Ice-T’s “Cop Killer” furor, sending parent company Warner Bros. into a panic. Warner refused to distribute Live and Let Die, abruptly ending its deal with Cold Chillin’ Records. G Rap’s violent gangland tales, once merely seen as edgy, suddenly became a liability in the early ’90s climate of censorship. Cold Chillin’ was forced to release the album independently in a limited way, and the fallout irrevocably altered both the label’s and the artist’s trajectory. By 1993, Kool G Rap and DJ Polo parted ways, ending a prolific duo run that had produced three influential albums. “I just felt like two dudes can’t eat off the same plate forever,” Kool G Rap later reflected, noting that their partnership had become lopsided—he was the one writing and shaping the music while Polo was “the DJ” and not an equal creative force. Having “thanked him enough” after seven years and three albums, G Rap struck out on his own, determined to carve a solo identity that could stand alongside, or beyond, the Juice Crew legend he helped build.

Even as he sought a fresh start, the ghosts of Cold Chillin’ followed. The pioneering label that nurtured G Rap (alongside Big Daddy Kane, Biz Markie, Roxanne Shanté, and more) was itself on its last legs. It had been rocked by the infamous Biz Markie sampling lawsuit in 1991 (Gilbert O’Sullivan vs. Biz Markie), a case that changed hip-hop sampling forever. Then came the loss of its major distribution: after the Live and Let Die fiasco, Warner Bros. cut ties, leaving Cold Chillin’ without a powerful backer. By 1995, the label had secured a new deal with Sony’s Epic Records, largely because Epic wanted G Rap on board. The partnership was fleeting—yielding only two albums, Grand Daddy I.U.’s Lead Pipe (1994) and G Rap’s 4, 5, 6—but it gave Kool G Rap’s solo debut a much-needed national push. 4, 5, 6 would fittingly become Cold Chillin’s final release of new material before the storied label folded, marking the end of an era even as it introduced a new one.

If industry drama wasn’t enough, a more tangible menace cast its shadow over G Rap during the making of 4, 5, 6. The Queens-bred MC has remained tight-lipped about specifics, but multiple accounts suggest he ran afoul of some serious underworld figures—enough that a contract was allegedly put on his life. Fearing for his safety, G Rap went on the move, staying a step ahead of potential hitmen. He ultimately holed up in Bearsville, a secluded hamlet near Woodstock, New York, to record the album in relative secrecy (Producer T-Ray later described the setup as a “cabin upstate,” and indeed Bearsville Studios provided on-site housing where artists could live while recording). This retreat to the woods was a far cry from the streets of Corona, Queens, that shaped him, and it injected 4, 5, 6 with an atmosphere of danger and isolation. Upon wrapping the sessions, Kool G Rap didn’t even stick around to celebrate; he quietly uprooted his family and relocated across the country to Arizona, not informing even close friends or his label of his whereabouts. Survival, it seemed, had to come before rap stardom. This harrowing context seeps into 4, 5, 6’s very fiber—the album sounds paranoid, battle-ready, often somber, as if recorded with one eye peeking over the shoulder.

Given the tumult surrounding its birth, it’s little surprise that 4, 5, 6 carries a darker, more mournful tone than Kool G Rap’s earlier work. Gone are the playful, if gritty vibes, of 1989’s Road to the Riches; in their place is something colder, heavier with regret. The production, split among a tight crew of four, is minimalist East Coast boom-bap painted in midnight hues. Longtime G Rap associate Domingo “Dr. Butcher” Padilla handles about half the album, while esteemed Diggin’ in the Crates producer Buckwild, crate-digging maestro T-Ray, and the lesser-known Naughty Shorts contribute key tracks. Together they craft a musical backdrop that is often stark and brooding—dusty drums, eerie loops, melancholy soul samples—an ideal canvas for G Rap’s crime narratives. There’s an audible lack of polish that works in the album’s favor; it feels underground and insulated from commercial pressures, yet the quality of beats remains high. This is hip-hop scored for dimly lit tenement hallways and smoky backroom gambling tables, far from Marley Marl’s radio-friendly funk of years past. In fact, recording in the wilderness of Bearsville might have enhanced the gritty vibe: G Rap himself noted the album had a “dark, grimy street sound,” as if the wooded isolation channeled him back into NYC’s underbelly.

The title track opens the album like a scene from a street novel. Over a dusty break laid by Dr. Butcher, Kool G Rap steps into the role of an ace cee-lo gambler, narrating a high-stakes sidewalk dice game in vivid detail. The intro skit drops us right into that corner tableau—taunting voices, cash hitting the pavement—before G Rap’s gravelly voice cuts in to share the intricacies of his cee-lo game. He laces his verses with so much slang and specificity that outsiders might get lost, but that’s the point: authenticity over accessibility. Every toss of the dice comes alive through his words, and naturally, our narrator “always walks away the winner." It’s a masterclass in detail, with Kool G Rap’s knack for street journalism on full display. This attention to realism, born from the Juice Crew tradition of storytelling, anchors the album’s narratives. Whether he’s describing a hustle or a homicide, G Rap paints with a reporter’s eye and a poet’s tongue, grounding his mafioso visions in something that feels like lived experience.

As 4, 5, 6 progresses, it plunges deeper into the underworld psyche. “Executioner Style” is one of the album’s most unsettling cuts—here G Rap assumes the persona of a remorseless contract killer, unloading violence with grim creativity. Over a slow-rolling, menacing beat, he rattles off macabre punchlines with a half-crazed glee: “I’m spitting out the lead, see, to split your head like the Red Sea,” he growls, mixing biblical imagery with street vengeance. It’s the kind of over-the-top line that almost dares you to laugh at its audacity, even as it leaves a chill. G Rap’s signature lisp only amplifies the sinister charisma—a hitman with a gift for gab. Yet as the song’s title implies, this is execution as style: murder described with a virtuoso lyricist’s flair. No detail is spared; one can practically see the muzzle flashes and panicked crowds in his rhymes. The track’s cathartic mayhem harks back to Live and Let Die’s cartoonish ultra-violence, but there’s a more palpable pain lurking behind the mayhem on 4, 5, 6. Unlike earlier efforts where gore sometimes served for shock value, here the bloodshed carries a somber aftertaste, as if G Rap is acknowledging the real human toll behind the gangster exploits.

Nowhere is that clearer than on “Ghetto Knows” and “For My Brothaz,” the album’s emotional core. On “Ghetto Knows,” produced by Naughty Shorts, G Rap offers a panoramic survey of urban chaos—a place where “human life becomes meaningless” amid rampant crime and despair. Over a haunting, serious-toned beat, he plays both observer and participant. One verse finds him channel-surfing through nightly news carnage, overwhelmed by the endless reports of killings; in another, he’s suddenly the target, narrowly escaping an ambush by “a bloodthirsty crew,” as the song ends with the hunter becoming the hunted. The atmosphere is tense and claustrophobic. You can feel the paranoia that must have been weighing on G Rap’s real life during those recordings—the sense that danger is around every corner.

“For My Brothaz” goes even deeper into introspection. Over T-Ray’s mournful piano-laced production, Kool G Rap drops the tough posture to deliver a heartfelt eulogy for two of his fallen friends, Puzzle and K-Von. These were real people from G Rap’s circle, lost to the same street ambitions that he so vividly chronicles. His voice takes on a tone of regret and longing as he pours out memories—lamenting “the potential unrealized” when young lives are cut short. The track is strikingly personal; G Rap reflects on how chasing the glory of the drug game led his brothers to early graves. In a genre (and an era) where machismo often demanded emotional invulnerability, “For My Brothaz” stands out as a moment of genuine mourning. It’s the sound of a man who has seen too many wakes, carrying survivor’s guilt and using his music to pour out a little liquor for the comrades who didn’t make it. This song’s introspective, grieving spirit marks a clear evolution from the Kool G Rap of the ‘80s. Back then, alongside DJ Polo, he dazzled listeners with tongue-twisting braggadocio and gritty street tales, but rarely did he pull back the curtain on his feelings. On 4, 5, 6, amid the carnage, we hear a veteran MC wrestling with mortality and loss—a wiser, perhaps wearier G Rap who’s seen the flip side of the fast life.

Not that G Rap has lost his taste for victory laps. The album balances its darkness with a few moments of triumph and luxurious boasting, reminding us that the coin of gangsta rap has two sides: the pain and the glory. “Blowin’ Up In the World” is an autobiographical anthem of success, set to a surprisingly bright backdrop courtesy of Buckwild. The producer digs into a familiar sample—Bobby Caldwell’s buttery soul classic “What You Won’t Do for Love”—flipping it into a warm, head-nodding loop. Over this soulful sway, Kool G Rap chronicles his climb from hungry street kid to rap kingpin. The contrast is striking: G Rap opens recalling himself as “a kid from Corona with a G.E.D. diploma, with more ribs showing than Tony Roma’s”—a stomach-growling portrait of ‘80s NYC poverty – and then fast-forwards to the present, where he’s one of the most revered MCs alive. In between, he details how he first resorted to illegal hustle to make ends meet, before realizing his lyrical skills could be his ticket out of the gutter. It’s a rags-to-riches story, classic hip-hop in theme, but delivered with Kool G Rap’s unsentimental realism. The joy in his voice is tempered; you sense he hasn’t forgotten the cost of the journey.

Likewise, “It’s a Shame” finds G Rap reveling in ill-gotten opulence over a smooth, mid-tempo track. Over plush bass and a hint of R&B crooning, he swaggers through verses about private jets, custom Rolexes, and his loyal “down ho, a Foxy Brown ho” (a nod to blaxploitation icon Pam Grier) named Tammy riding by his side. The song is pure braggadocio, Kool G Rap styling as a high-rolling mafioso who’s “got it all.” Yet, tellingly, even at his most boastful, he can’t escape a pang of conscience—he throws in a line acknowledging “it’s a shame what I gotta do to get the money." That passing lyric, sung in the hook by guest vocalist Sean Brown, hints at the guilt beneath the glamour. It’s as if G Rap knows the lavish lifestyle he’s flexing comes with soul-crushing baggage. On the surface, it bumps like a summer single, but beneath, there’s moral ambivalence.

All these threads come together on the album’s showpiece collaboration, “Fast Life,” which pairs Kool G Rap with a young Nas in a Queens kingpin summit. In 1995, this song was a hip-hop dream team because Nas had just blown the world away with Illmatic a year prior, and G Rap was one of his admitted idols. Their chemistry on “Fast Life” is palpable, a cross-generational dialogue between two masters of New York street lore. Over a polished Buckwild track built on a loop of Surface’s silky R&B hit “Happy,” the two MCs trade verses dripping with mob boss bravado. G Rap opens up, flaunting “cee-lo rollers, money folders, sipping Bolla, holding mad payola,” bragging about “slanging that coke without the cola”—lines that cement him as the O.G. who can make hustler life sound like high poetry.

Nas follows with his own blend of slick talk and reflection, rapping “Cristal like it’s my first child, licking shots Holiday style/Rocking Steele sweaters, Wallabee down,” name-dropping fly gear and fine champagne with the hunger of an upstart who can’t believe he’s finally living the fast life he once only imagined. The back-and-forth has an almost ceremonial feel; Kool G Rap has said he viewed “Fast Life” as a passing of the torch to Nas, and indeed Nas (billed pointedly as “Nas Escobar” on the single, embracing the crime-lord moniker G Rap helped inspire) rises to the occasion as heir apparent. In Queensbridge lore, this track is significant—it bridged the gap between the borough’s ‘80s pioneers and the ‘90s new school. Nas, the pride of Queensbridge Houses, stands shoulder-to-shoulder with Corona’s veteran warlord, linking two eras of Queens crime rap mythology.

Even as the Cold Chillin’ era ended around him, the label would spend its final years releasing mere compilations and lost tapes before shuttering—G Rap doubled down on the qualities that made him a pioneer. He didn’t chase radio trends or water down his content; instead, he delivered an album that reflected the truth of his circumstances and the streets he came from. The mood, as dark as it was, rang true. The mastery of narrative—whether depicting a dice game, a mob hit, or a fallen friend’s funeral—remained unparalleled. One can appreciate how Kool G Rap’s unapologetic mastery of detail and mood elevates the album into the pantheon of ’90s rap, even if it’s rarely given the same reverence as more commercially celebrated classics.

This record signaled the end of one chapter (the Juice Crew/Cold Chillin’ reign) but simultaneously served as a bridge to the future. Nas’s appearance literally puts the next era on the cover with him, and many of the 2000s “street lyricists” owe G Rap a debt for the trails he blazed here. And unlike many “mafioso rap” records that followed, 4, 5, 6 never loses sight of the humanity beneath the gun smoke. Its somber production and G Rap’s tempered, knowing delivery imbue even the flashiest boasts with an undercurrent of gravity. This is why the album endures as a cult classic: it thrills you with wordplay and underworld drama, while also evoking the weight of blood on the pavement.