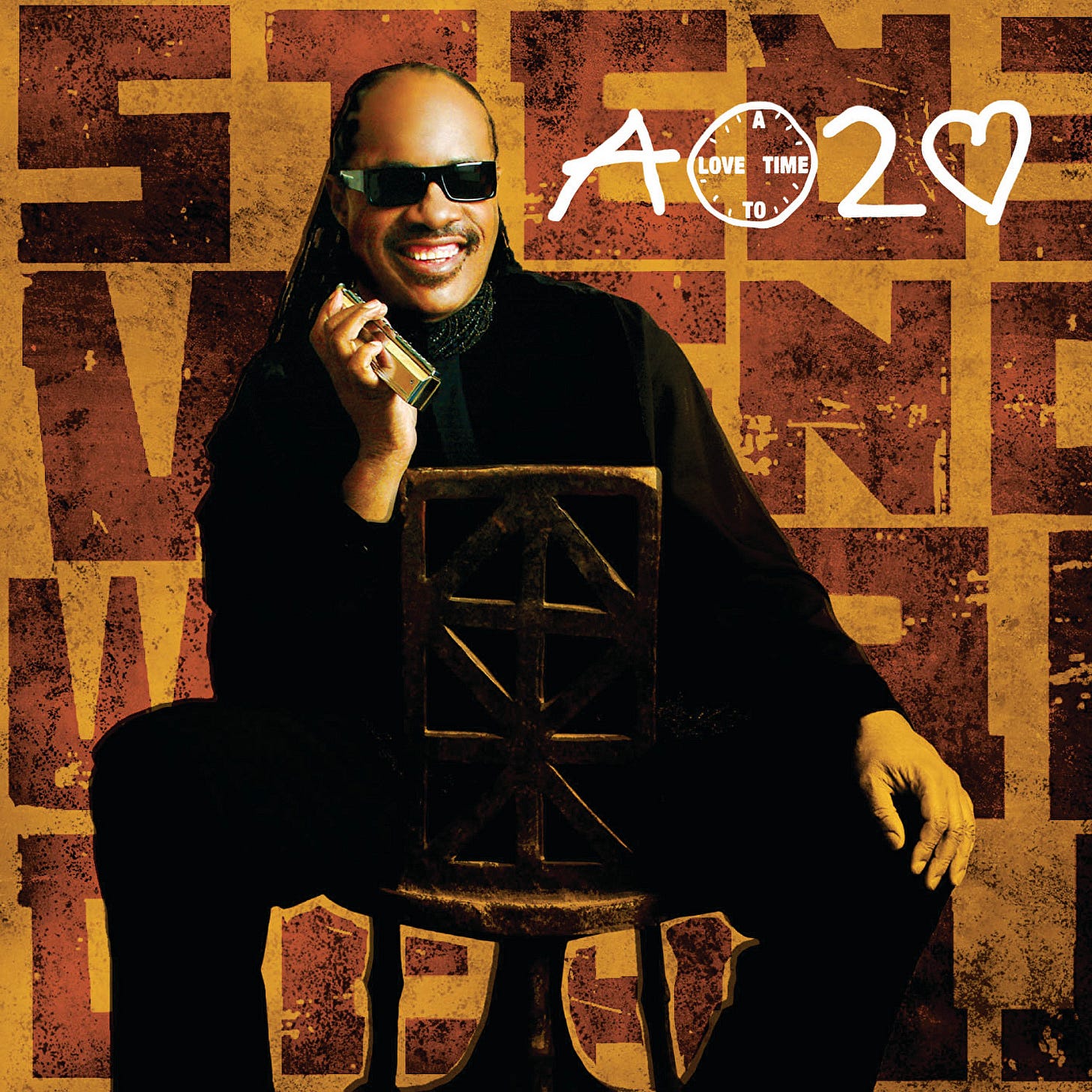

Anniversaries: A Time to Love by Stevie Wonder

A Time to Love may not eclipse the shadow of Stevie Wonder’s towering classics, but it certainly breaks the long drought of new material with style, soul, and substance.

When A Time to Love, expectations were sky-high—this was Stevie Wonder’s first new studio album in ten years, and many hoped it would reclaim the genius of his classic 1970s run. Initial reviews in 2005 were respectful but lukewarm; some people were frustrated that after such a long wait, Wonder mostly revisited the sound of his “classic period” without breaking new ground. Yet, with the benefit of time, A Time to Love reveals itself as something more nuanced: a reconciliation of Stevie Wonder’s two musical eras—the socially conscious, genre-blurring innovator of the late 1960s and 1970s, and the smooth, radio-friendly hitmaker of the 1980s and 1990s. In 2025, the album can be appreciated as both a return to form and a heartfelt bridge between generations of soul music.

Rather than choose between the politically aware Stevie of Innervisions and the love-balladeer of In Square Circle, Wonder crafted A Time to Love as a blend of both sensibilities. The question on listeners’ minds in 2005—which Stevie Wonder would show up, the anthem-writing activist or the silky R&B crooner?—was answered with a bit of each. For every socially or spiritually “forward-moving” song with a message, there’s a gentle, heart-on-sleeve number to balance it. This equilibrium echoes through the album’s sequencing and themes. Uptempo funk jams and message songs sit comfortably alongside quiet-storm ballads, mirroring the dual legacy of an artist who once wrote both “Living for the City” and “I Just Called to Say I Love You.” Notably, despite being recorded with polished 21st-century digital production, many of these tracks exude a vintage warmth—aside from their modern sonic sheen, they could have easily found a home on albums like Talking Book or Hotter Than July, so faithful are they to Wonder’s classic spirit. The production is lush and digital, yes, but it does not smother the soul; instead, it highlights how Wonder updated his 1970s artistry for a new millennium.

Listen closely and you’ll hear echoes of early Motown and 1970s Stevie woven into modern R&B arrangements. In an era (the mid-2000s) when much of R&B had turned to brash materialism or explicit themes, Wonder’s songwriting on A Time to Love was almost nostalgic in its purity—recalling the simplicity and innocence of early Motown without sounding trite. This is a mature artist writing about love and hope with earnestness that feels refreshing amid the irony of contemporary pop. The album’s very thesis is in its title: that after times of war, strife, and superficiality, what the world needs is “a time to love.” Stevie himself described the title track’s message plainly: “There’s been a time for war…we now must set aside a time for love…now more than ever, [we need] to bring love back to the forefront.” That thematic focus gives the record a unifying optimism and spiritual uplift reminiscent of Wonder’s socially conscious masterpieces.

Fittingly, the album is bookended by two songs that encapsulate its balance of urgency and uplift. On one end is “So What the Fuss,” a slamming funk workout that finds Wonder in classic form laying down clavinet-style grooves and a distorted bass line reminiscent of “Superstition.” This track—the lead single—pairs Stevie with fellow icon Prince (who contributes a stinging lead guitar) and R&B vocal trio En Vogue, creating a multi-generational funk summit. Over a churning beat and horn stabs, Wonder pointedly asks why people are fussing instead of taking action, effectively calling out complacency and trivial distractions. “If we’re not serious about what’s going on, ain’t no need to talk about it…so what’s the fuss?” he seems to suggest. It’s one of Wonder’s most straight-ahead, hard-grooving funk songs in years, and it delivers a bristling shot of energy and social commentary that harks back to his ’70s protest-funk anthems. Even if it didn’t storm up the charts in 2005, “So What the Fuss” stands today as a statement that Stevie Wonder could still “bring the funk” and speak his mind, now with the authority of elder statesmanship. It’s the kind of lively, gritty track few would expect from a 55-year-old legend—yet there he was, funky and relevant as ever, effectively telling the new generation: pay attention to what matters.

On the other end of the spectrum is the nine-minute title song “A Time to Love,” an anthemic mid-tempo ballad that serves as the album’s grand finale and heart. An expansive and elegant—a soulful plea for unity and compassion in the tradition of Wonder’s classic message songs (“Love’s in Need of Love Today” comes to mind). Co-written with neo-soul songstress India.Arie (who duets with Wonder), and graced by a cameo from Paul McCartney on acoustic guitar, the track carries considerable symbolic weight. India.Arie’s lyrical touch is evident in the song’s poetic call for love to conquer hate, while Wonder’s melodic genius shines in the warm chorus that swells with gospel-tinged backing vocals. The result is a modern civil-rights era song, updated for the 2000s: its message of love and peace is delivered as strongly and convincingly as any song Wonder’s ever done. Hearing Stevie and India trade lines about making love the priority “now more than ever” is goosebump-inducing—it’s as if the torch of socially conscious soul is being passed and shared between generations. With McCartney’s guitar adding subtle rootsy texture (a Beatle lending support to Motown’s genius, decades after their mutual 1980s hit “Ebony and Ivory”), “A Time to Love” swells into a true anthem. In hindsight, it feels like Stevie Wonder’s benediction to the world at that mid-2000s moment: a compassionate plea set to music, urging humanity toward its better instincts. As the album’s concluding statement, it reinforces Wonder’s identity as pop music’s gentle prophet, tying the project together on a note of hope.

Between those two bookends, A Time to Love explores the many shades of love that Wonder referenced in the album’s concept—romantic love, familial love, spiritual love, and love for humanity. The romantic songs here carry a wisdom and warmth that distinguish them from the formulaic R&B ballads of the 2000s. Take “Sweetest Somebody I Know,” a mid-tempo love song that glows with the innocence of a ‘60s Motown hit even as it reflects an adult perspective. Over breezy, Latin-tinged jazz chords and a gently swaying groove, Wonder sings earnest praises of a cherished lover with disarming sincerity. There’s an almost retro sweetness in lines that express simple admiration and gratitude, yet it never descends into schmaltz or cliché. Indeed, these are love songs of maturity, crafted with care and patience. One can imagine that if Stevie’s early-‘70s tune “Happier Than the Morning Sun” was the exuberant love of youth, then “Sweetest Somebody I Know” is that young couple decades later—love grown deeper, mellowed like fine wine. It’s a testament to Wonder’s songwriting that he can evoke that same wide-eyed devotion of his youth while infusing it with the gravitas of lived experience. The track’s melody is sophisticated yet hummable, and Stevie’s vocal, still honeyed and agile in his mid-50s, sells every word. In its gentle joy, “Sweetest Somebody” indeed feels like it could have sat comfortably alongside tracks from Talking Book—it has that classic Wonder touch—except now the production is digital and the perspective that of a seasoned lover.

Similarly, “How Will I Know” (not to be confused with the Whitney Houston hit) plays like an update of a classic format: the tender father-daughter duet. This jazzy, cabaret-inflected ballad features Aisha Morris—Wonder’s daughter, the very baby whose newborn cries were immortalized in 1976’s “Isn’t She Lovely”—now singing lead vocals as an adult. The song itself is a delicate contemplation of love’s future: How will I know if I’ll be able to love someone truly? Aisha’s light, graceful voice handles the verses, while Stevie joins in harmonies and on harmonica, almost like a guardian guiding the melody. The effect is quietly heartwarming—a full-circle moment spanning generations of Black music lineage. The track leans into jazz-soul, with sophisticated chord changes and brushed percussion giving it an intimate club feel.

It evokes the innocence of Motown’s earliest sentimental ballads (one can hear faint echoes of Smokey Robinson’s romanticism), yet it’s grounded in the real emotions of a father and grown child. Crucially, it never turns saccharine—Wonder’s sincerity and the genuine family chemistry make sure of that. By the time the song modulates for its final chorus (in a key change subtly placed around the three-minute mark), any listener with a heart will likely have a tear in their eye. In a broader sense, “How Will I Know” and the album’s other love-centered songs show Stevie Wonder drawing on the sweetness of his 1960s Motown roots—think of his youthful hits like “My Cherie Amour”—but writing from the vantage point of a 55-year-old man who’s seen life’s ups and downs. The result is romantic music that feels classic yet earned, never cheap. It’s no wonder that even some initially skeptical critics came to regard “How Will I Know” as a late gem in Wonder’s songbook, perhaps the album’s most poignant cut.

From a sonic perspective, A Time to Love is a polished affair, reflecting the digital recording techniques of its era, yet it manages to avoid the sterile feel that plagued some of Wonder’s late-’80s/’90s work. The album is richly layered—glossy synthesizers, programmed beats, and digital effects share space with live horns, organic percussion, and Stevie’s beloved keyboard instruments (yes, there’s even some funky clavinet in spots). It’s true that at 77 minutes, the album could have been tightened—a few ballads in the first half (like the pretty but lightweight “Moon Blue”) do flirt with easy-listening territory. But even the slickest tunes are redeemed by Wonder’s sincere delivery and musical touches that throw back to his prime. For instance, he dusts off his famous harmonica for a gorgeous solo on the sentimental “From the Bottom of My Heart,” instantly imbuing that song with classic soul texture. Later, on the gentle bossa nova-inflected “Positivity”—a feel-good song featuring Aisha again—the breezy groove and hopeful lyrics echo Stevie’s Motown days, even as the production is thoroughly modern. It’s fair to say that the album’s glossy digital veneer both enhances and tempers the songs’ warmth. The polish gives the record a cross-generational appeal—it’s smooth enough for adult R&B radio, but the heart in the songs is pure vintage Stevie. In hindsight, this approach bridges the eras: had Wonder tried to slavishly recreate the sound of his 1970s albums, it might’ve felt false, but by using modern tools to channel an old soul, he made the album sound current in its time while rooted in classic songwriting.

Where does A Time to Love sit in Stevie Wonder’s towering discography? At the time of release, it was hailed in some quarters as a comeback—even Stevie’s camp touted it as a return to the quality of old. Others were more measured, viewing it as a solid effort that didn’t quite reach the genius of the 1970s. With 20 years of hindsight, the consensus leans toward A Time to Love being a triumphant return to form in spirit, if not outright on the level of his magnum opuses. No, it’s not Innervisions or Songs in the Key of Life—few albums in history are as revered. But it was arguably Stevie’s best and most confident album since 1980’s Hotter Than July, successfully reconnecting the threads of his artistry. It bridges the two eras of his career: one can hear the youthful fire and inventiveness of the classic period and the mellow, inclusive warmth of his later adult-contemporary phase coming together in harmony. The album feels like a victory lap that’s also a heartfelt statement: Stevie proving he still has it, and using that platform to spread love and social consciousness for a new era.