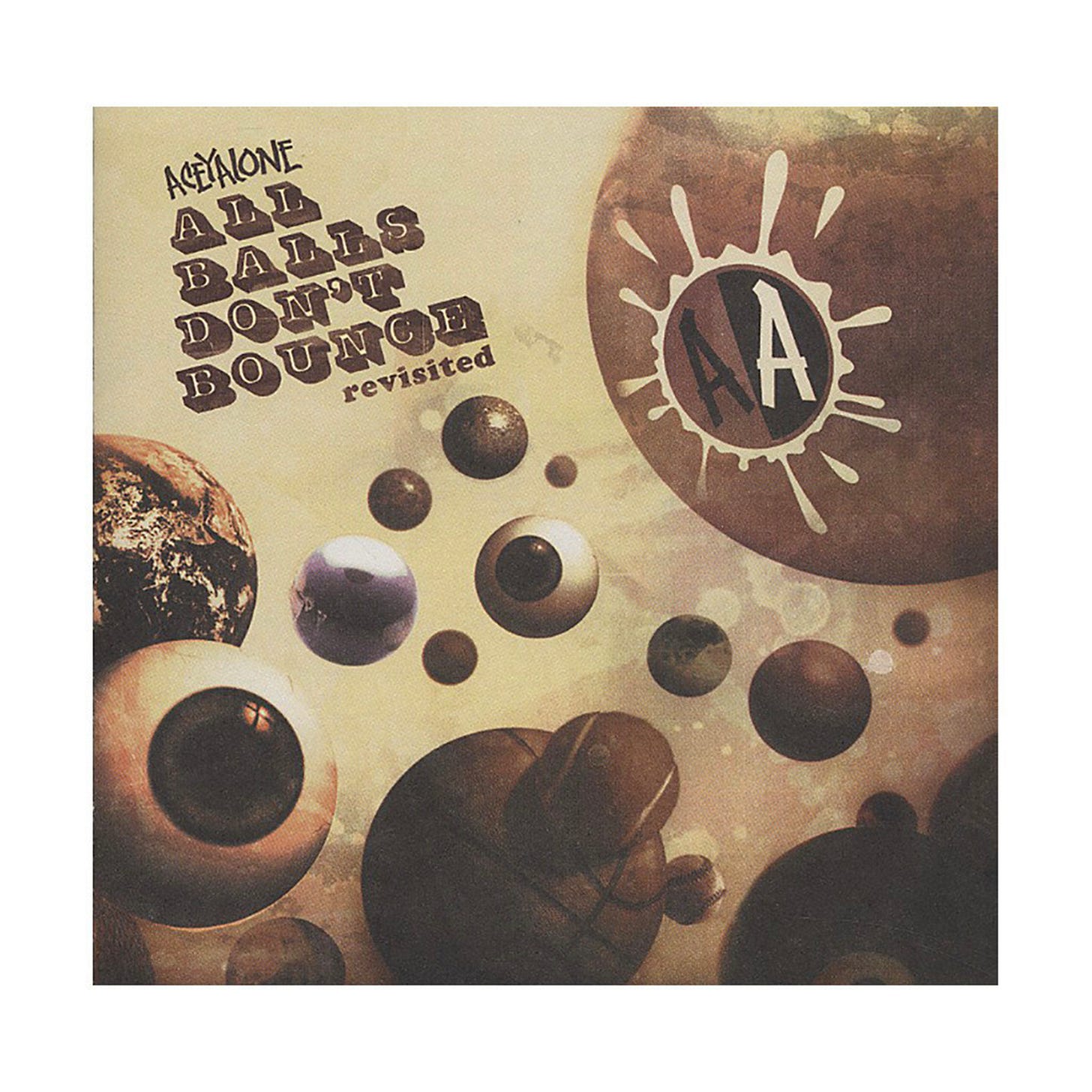

Anniversaries: All Balls Don’t Bounce by Aceyalone

Though it flew under the radar in 1995, the album became a bedrock for the Los Angeles underground hip-hop renaissance. Aceyalone inspired countless artists who followed.

Nearly three decades ago, amid the reign of G-funk and gangsta rap on the West Coast, a different kind of hip-hop statement emerged from South Central Los Angeles. Aceyalone—born Edwin Hayes, Jr.—released his solo debut All Balls Don’t Bounce on Capitol Records. It landed with little fanfare commercially and was taken out of print not long after its release due to label politics. Yet in the years since, this “aggressively non-commercial” project has been recognized as a visionary landmark, marking the rise of a major pioneer in L.A.’s underground hip-hop scene. Aceyalone was already known as a breakout member of the trailblazing collective Freestyle Fellowship, which in the early ’90s had proven that not every Los Angeles rapper had to conform to gangsta rap’s dominance. With All Balls Don’t Bounce, Aceyalone arose as the godfather of the L.A. underground by unapologetically forging his own path.

From the outset, All Balls Don’t Bounce was a statement of independence and originality. Even its title is a sly metaphor: in Aceyalone’s world, “just because people put you in a certain category (balls) doesn’t mean you will act like everybody else (bounce).” In other words, not all “balls” bounce the same way—and Aceyalone was a ball that refused to bounce to anyone else’s beat. In a scene saturated with violent bravado and nihilistic cool, Aceyalone stood apart; his music pointedly lacked the standard West Coast tropes of that era, like gang violence or misogynistic posturing. This absence immediately made him an outlier—a self-proclaimed “Mr. Outsider”—within 1995’s hip-hop landscape. On the track “Mr. Outsider,” the soul-searching centerpiece of the album, Aceyalone lays out his mission. Over a laid-back, east-coast-flavored beat by The Nonce (a deliberate contrast to Dr. Dre’s glossy funk of the same year), he sketches his life as “a n**a that the world don’t care about,” describing how he eschewed the gang life for a more “Cooley High-like” existence and began plotting a way to “shift how people listen to music.” “It’s all about being a fighter,” Aceyalone intones on the track, “Use the guide to open up your mind a little wider.”

At the core of All Balls Don’t Bounce is Aceyalone’s remarkable lyrical craft—a fluid, improvisational rhyme style that drew immediate comparisons to the greats. Like Rakim on the opposite coast, Aceyalone wove intricate patterns with a cool confidence, echoing Rakim’s assured complexity even as he broke new ground on the West. Years spent honing his skills at South Central’s Good Life Café open-mic and the Project Blowed workshops gave Aceyalone an improvisational agility that set him apart from his peers. He could freestyle with the best of them, but he was also a deeply cerebral writer, infusing verses with philosophy, humor, and abstract imagery. Importantly, he never lost the battle rap competitiveness in his DNA—he was out to prove himself the best MC on the planet—but he elevated battle rhymes to a high art.

On the album’s lead single “Mic Check,” for example, he becomes what’s called a “lyrical dynamo,” unfurling tongue-twisting braggadocio that’s as inventive as it is self-assured. “I love putting pressure on the lesser competitive,” Aceyalone snarls on the track. “Inferior you’re determined, vermin…/I got the elephantitus styles, superior stroke/Of genius, I spoke, and hell broke loose/I saturated the streets, ’fatuated by drum beats.” In these bars, Aceyalone flexes a vocabulary and rhythmic dexterity virtually unheard of in West Coast rap at the time—a torrent of wordplay that overwhelmed any notion that L.A. MCs couldn’t be as “lyrical” as their East Coast counterparts.

Aceyalone’s unshakable confidence as an MC was matched by a desire to push hip-hop’s artistic boundaries. All Balls Don’t Bounce wasn’t about radio hits or flashy production; it was about redefining the craft on Aceyalone’s own terms. The album’s production, handled mainly by a cohort of underground L.A. beatmakers (The Nonce, Mumbles, Vic Hop, Chillin Villain Empire, and others), is intentionally sparse and jazz-inflected, designed to let Acey’s rhymes shine. Instead of the lush, high-budget G-funk sonics of mid-’90s L.A., All Balls opts for minimalism and mood. The beats ride dusty breakbeats, subtle bass lines, and muted melodic loops where pianos and vibraphones take the place of squealing synths. This was jazz-rap with a South Central twist, carrying on the open-eared musicality pioneered by groups like The Pharcyde and Freestyle Fellowship themselves.

On “The Greatest Show on Earth,” produced by Mumbles, Aceyalone truly treats the track like a jazz soloist would treat a standard. Over a dizzying bass line and cascading vibraphone riffs (sampled from Horacee Arnold’s avant-garde jazz piece “Orchards of Engeti”), Acey scats and syncopates his flow at breakneck speed, never missing a beat. His voice becomes an instrument, improvising around the beat’s off-kilter contours. It’s a tour de force in technical rapping that still feels musical, even soulful. A similarly daring moment comes with “Headaches and Woes,” where producer Punish flips the vibraphone intro of jazz great Milt Jackson’s “Moonray” into a haunting loop. Aceyalone starts by spilling out his anxious thoughts in rhyme, then, in the song’s final minute, the beat dissolves into chaotic free jazz and Acey slips into spoken-word poetry. It’s an abstract, theatrical turn that underlines the album’s refusal to play by anyone else’s rules. Such production choices were unorthodox in 1995, but they served to amplify Aceyalone’s words rather than overshadow them.

Whereas All Balls Don’t Bounce lays down a manifesto, it does so through a series of stunning “textbook” demonstrations of MC ingenuity. The title track “All Balls” itself opens the album by establishing Aceyalone’s theme of nonconformity. Originally appearing on the 1994 Project: Blowed compilation, “All Balls” (produced by The Nonce) sets the tone with its refrain and message: all balls don’t bounce, meaning not every artist will follow the same trajectory or rules. Aceyalone uses the song to plant his flag as an individualist in hip-hop—one who might be in the same “game” as others but refuses to play it the usual way. Perhaps the most audacious exhibition of skill on the record is “Arhythamaticulas.” Over an abstract, uptempo track by Chillin Villain Empire, Aceyalone launches into an almost surreal flow, chopping up bars and stretching syllables in ways that defy the usual 4/4 time constraints. It’s essentially a manifesto for artistic freedom. Aceyalone uses the song to implore fellow rappers to let go of rigid notions of hip-hop structure. “Brother, I say to you—but don’t you believe or be deceived by the hip-hop that you breathe,” he urges, “I am multidirectional, I move randomly and professional, intellectual with perpetual…”

Aceyalone doesn’t carry this revolution alone. All Balls Don’t Bounce also thrives on collaboration and community, showcasing the dynamic Project Blowed scene that Aceyalone helped cultivate. Fellow Good Life alums Abstract Rude and Mikah 9 (of Freestyle Fellowship) appear multiple times, their presences reinforcing the album’s sense of collective mission. On “Knownots,” one of the album’s undeniable high points, Aceyalone teams up with Abstract Rude and Mikah 9 for a boisterous cipher that crackles with competitive camaraderie. The title “Knownots” is a play on “know-nots”—those who don’t know—and the track’s purpose is to wake up any listeners sleeping on the West Coast’s lyrical talent. Over a bouncing beat by Vic Hop, the three MCs tag-team verses, riffing off each other’s words and styles. They “signify” their skills joyously, each verse aiming to outdo the last in a showcase of virtuosity that is also simply fun. You can sense the decades of open-mic battles and friendly one-upmanship fueling their rhymes. The energy is infectious—“Knownots” feels like an underground party on wax, a celebration of the very scene that birthed these artists.

Abstract Rude also joins Aceyalone on the earlier track “Deep and Wide,” a mellow, melodic number where both rappers ride a dreamy beat in smooth, unhurried flows. Placed amid the album’s more frenetic tracks, “Deep and Wide” shows Aceyalone’s versatility; it’s a moment of almost meditative vibe, as if the two veteran MCs are demonstrating that restraint and groove can captivate just as well as rapid-fire pyrotechnics. The chemistry between Aceyalone and Abstract Rude (who would later formally collaborate as the A-Team) is evident, adding an extra layer of texture—a dialogue between kindred spirits. Even without knowing the entire Project Blowed history, a listener can tell that All Balls Don’t Bounce arises from a community of artists pushing each other. This communal spark amplifies the album’s impact, making it not just a solo debut but a snapshot of an entire movement coalescing around Aceyalone’s leadership.

For all his focus on lyrical gymnastics and big-picture ideas, Aceyalone also takes time on All Balls Don’t Bounce to explore more intimate storytelling, particularly in his nuanced portrayals of women—a rarity in mid-’90s hip-hop. Two tracks in particular stand out: “Annalillia” and “Makeba.” On “Annalillia,” Aceyalone shows a surprisingly playful, even vulnerable side. The song is built on a light, buoyant beat (courtesy of The Nonce) and finds Acey recounting his attempts to woo a woman named Annalillia he encounters at various nightspots. Unlike the usual hyper-masculine conquest tales, Aceyalone’s story is relatable and tinged with self-deprecating humor—he tries his best lines on her, only to discover she’s just not interested. No bitterness or macho is posturing in his reaction. Instead, he almost chuckles at the situation, recognizing that sometimes the chemistry just isn’t there. It’s a refreshingly down-to-earth narrative that humanizes both him and the woman, free of the misogyny that plagued so many rap songs of the era.

In contrast, “Makeba” takes on a more somber, reflective tone. Over a moody, haunting backdrop produced by Mumbles, Aceyalone reminisces about a lost love from his youth—a teenage romance with a girl named Makeba who vanished from his life without warning. The track has a wistful, late-night feel; Acey’s delivery is subdued yet emotive as he grapples with unanswered questions. “She disappeared into the night,” he raps softly, conveying both the pain of abandonment and the understanding that life pulls people in different directions. There’s a serious emotional depth and maturity here. Aceyalone isn’t afraid to admit his vulnerability or reflect on what that relationship meant in shaping him. Importantly, both “Annalillia” and “Makeba” treat their female subjects with respect and empathy. In an era when many rap songs reduced women to one-dimensional props, Aceyalone’s approach was forward-thinking. He portrays these women as real people with agency—not conquests, not villains, just individuals in their own right. This ties back to the album’s overarching concept of Aceyalone as an outsider to hip-hop norms. By pointedly rejecting the genre’s common misogynistic clichés, he further establishes himself as one of those “balls” who refuse to bounce along with the crowd.

The influence of All Balls Don’t Bounce has far surpassed its initial reach. Though it flew under the radar in 1995, the album became a bedrock for the Los Angeles underground hip-hop renaissance. Aceyalone and his Freestyle Fellowship/Project Blowed brethren directly inspired countless artists who followed. Over the ensuing decades, you can trace Aceyalone’s stylistic fingerprints in the work of West Coast underground luminaries like Jurassic 5, Dilated Peoples, and the Visionaries, and even in later generations such as Blu, U-N-I, and Pac Div—all artists who helped bring literate, alternative L.A. rap to wider audiences. More broadly, the mind-expanding approach championed on this album can be felt in the rise of avant-garde and conscious hip-hop worldwide. It’s no exaggeration to say that All Balls Don’t Bounce quietly reset the possibilities for West Coast rap. Today, when superstar L.A. rappers like Kendrick Lamar earn Pulitzer Prizes and weave intricate concept albums, they do so in the wake of a path that Aceyalone helped pave. (Tellingly, Kendrick and his Black Hippy/TDE crew, though not direct disciples of Aceyalone, “share an unusual approach to rapping and creating albums” that parallels the iconoclastic spirit of the Good Life school.)

Aceyalone broadened the definition of what a West Coast MC could be: cerebral yet funky, battle-ready yet introspective, fiercely independent yet deeply rooted in community. He showed that Los Angeles hip-hop could be as intellectually stimulating and artistically bold as any movement in New York or elsewhere, shattering the coastal stereotypes of the time. The album remains imaginative and inventive, and its influence still stands out today. Its rough edges and experimental tangents only heighten its enduring charm, proving it was ahead of the curve by design. Aceyalone’s rhymes still crackle with the excitement of an artist discovering just how far he can push his craft, and the beats still provide a richly textured canvas for his verbal art. What was an “odd” or “non-commercial” detour back then now sounds like a prophetic statement of artistic integrity, a big middle finger to anyone who would try to pigeonhole hip-hop or limit who can participate in it. Aceyalone’s debut taught us that some artists won’t conform to the bounce of the mainstream—and in not bouncing, they change the game.