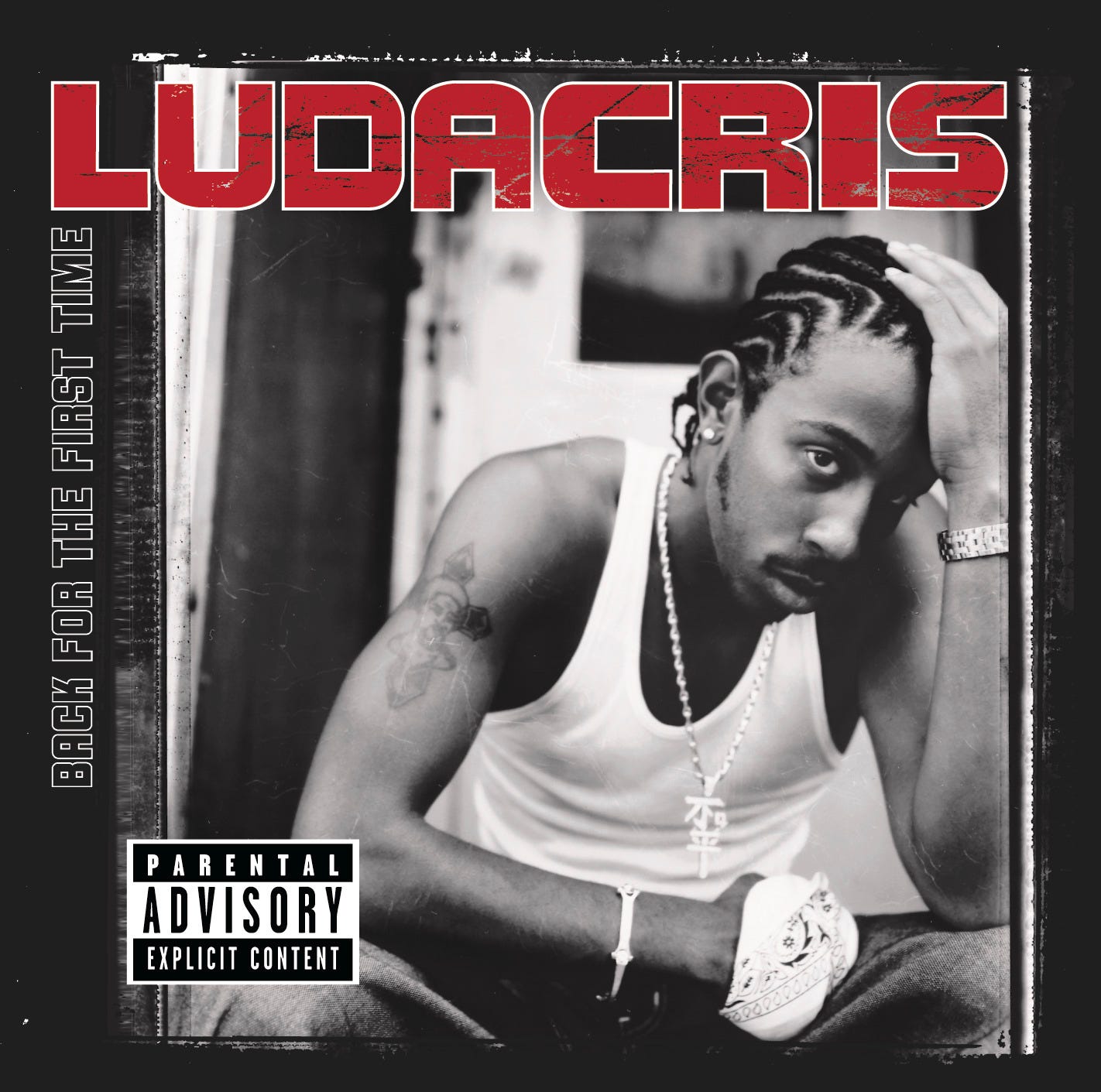

Anniversaries: Back for the First Time by Ludacris

Ludacris was back for the first time in 2000, and hip-hop hasn’t been the same since. One foot in the raw Dirty South of the late ‘90s, and one foot in the polished, crossover-minded 2000s.

Christopher “Ludacris” Bridges crashed the hip-hop party with Back for the First Time, a major-label debut that was a reinvention of his independent album Incognegro. Originally released on Ludacris’s own dime in 1999, Incognegro hustled its way to around 50,000 local sales and caught the attention of Def Jam’s then-new Southern outpost. Def Jam South signed the hungry Atlanta MC and promptly retooled his underground record for mass consumption, trimming a few tracks and tacking on four fresh ones. More than two decades later, Back for the First Time stands as a fascinating time capsule of a rapper straddling two worlds: the raw, gritty energy of Atlanta’s late-’90s underground and the glossy, party-ready sheen of turn-of-the-millennium mainstream rap.

The transformation from Incognegro to Back for the First Time was not just a simple reissue but a strategic overhaul. Ludacris noted that Def Jam “re-worked and re-released Incognegro under the title Back for the First Time” after signing him, removing two original songs and adding new material. In actuality, three Incognegro tracks (“It Wasn’t Us,” “Midnight Train,” and “Rock and a Hard Place”) were left on the cutting room floor, and four new cuts were introduced to the lineup: “Southern Hospitality,” “Phat Rabbit,” “Stick ’Em Up,” and a star-studded remix of “What’s Your Fantasy.” Each of these new additions shifted the album’s narrative and widened its appeal. They injected big-name producers and collaborators into the mix and tilted the vibe toward a broader audience—without entirely abandoning the rowdy spirit of the original record.

The most high-profile of the new tracks is “Southern Hospitality,” a Neptunes-produced banger that became one of Ludacris’s signature anthems. It’s a chest-thumping, elbow-throwing club track built on spare, buzzing synths and staccato drum claps. Interestingly, the album’s sequence tucks “Southern Hospitality” deep into the tracklist at number 14 (out of 16), rather than presenting it up front. This unusual placement means that a listener spends time in Ludacris’s gritty, Incognegro-era world before suddenly being hit with Pharrell Williams’s and Chad Hugo’s futuristic funk late in the album. While many albums front-load their hits, Ludacris’s choice (or perhaps Def Jam’s) to slot this track near the end gives Back for the First Time a second wind. The song itself is an unabashed celebration of Southern life and braggadocio: Ludacris shouts out “Cadillac grills, Cadillac spills” and a litany of ATL calling cards in a call-and-response hook that still gets clubs crunk. Ludacris ripped the beat, delivering his verses with boisterous flair that made the track infectious.

The other new additions likewise broadened the album’s scope. “Phat Rabbit,” produced by Timbaland, actually pre-dated the album—it first appeared on Tim’s 1998 Life from da Bassment project—but its inclusion gave Back for the First Time an extra dose of club-ready bounce. Over Tim’s playful, stuttering beat (all hiccuping bass and rapid-fire drums), Ludacris flexes a cheeky, sex-crazed flow, riffing on the chorus “shake your tail like a phat rabbit” with charismatic nastiness. The track’s techno-funky flavor, courtesy of Timbaland’s Virginia-rooted style, introduced Ludacris to listeners beyond the Dirty South; it’s an early example of his ability to rock any style without losing his identity.

“Stick ’Em Up” added cross-regional appeal of a different sort: it’s a murky, menacing duet with Southern rap legends UGK. Over a haunting piano loop and slumping bass courtesy of producer Shondrae (aka Bangladesh), Ludacris and UGK’s Bun B and Pimp C trade verses full of stickup-kid bravado and country slang. This track retains the Incognegro-level grit—it’s arguably the hardest song on the album—but the UGK feature gave Ludacris serious Southern cred. Finally, the remix of “What’s Your Fantasy” appended at track 15 doubles down on the original’s raunchy party vibe by adding Foxy Brown and Trina alongside Ludacris’s protégé Shawnna. Bangladesh’s beat remains a kinetic, head-nodding bed for all four rappers to spit their wildest sexual fantasies. Foxy and Trina, being high-profile female MCs, broaden the song’s appeal and give it a “remix as event” feel—a move clearly aimed at radio and club DJs who craved star power. The remix doesn’t drastically change the album’s narrative so much as it amplifies the party atmosphere and ensures that Back for the First Time ends on an exuberant, bawdy note.

Taken together, these new cuts reshape the album’s trajectory. Where Incognegro in its original form was a more insular showcase of a rising Atlanta talent and his crew, the Def Jam-sanctioned version opens the doors wide. The added tracks infuse the project with big hooks, famous friends, and a coast-to-coast flavor—effectively pivoting Ludacris from local hero to national player. One can almost feel the album’s center of gravity shift: early tracks still exude the Gritty South aggression and humor that got Luda noticed, while the latter portion veers toward a broader, radio-ready sound. Even the album sequencing reflects this evolution. Back for the First Time blasts off with a run of songs inherited from Incognegro—unvarnished, high-energy cuts that establish Ludacris’s personality—and only unleashes its crossover weapons in the final act (with “Southern Hospitality,” the “Fantasy” remix, and “Phat Rabbit” stacked back-to-back-to-back). It’s a bit like an underground mixtape that slowly transforms into a hits compilation as it plays.

Through all these changes, the glue holding the album together is Ludacris’s unmistakable lyrical presence. It’s surprisingly well put together, given how fully formed his swaggering, playful persona was, even in the Incognegro material. He bursts out the gate on the opener “U Got a Problem?” with outsized bravado and cartoonish wordplay, practically daring any doubters to step up. “I be that nigga named Luda/Alert, alert, it’s the ATL-ien intruder,” he bellows in the very first bars, proclaiming his arrival with the volume and audacity of a man who knew he was destined to blow. His delivery is dynamic and animated—he doesn’t just rap, he performs, stretching syllables, raising his voice to a comical bark, dropping punchlines with a sly grin you can practically hear through the speakers. At the time of Incognegro’s recording, Ludacris was still a local radio DJ (known as Chris Lova Lova on Atlanta’s Hot 97.5), and that radio-trained exuberance comes through on every track. He commands attention with a loud, confident flow that one critic later described as a “top-of-his-lungs shout” that somehow stays rhythmically on point. There’s a hungry, almost breathless quality to his rapping on these early tracks—the sound of an artist reveling in finally getting to cut loose on record.

Luda balances his aggressive Dirty South attitude with a hefty dose of humor and absurdity. He’s often riotously funny, even when he’s being “thuggish” or crass. The song “Ho” is a prime example: over a bouncy minimalist beat by Bangladesh, Ludacris dedicates an entire track to calling out promiscuous women (“You’s a hooooo!” goes the memorable hook), but he does it with such over-the-top comedic flair—exaggerating his pronunciation of “ho,” tossing in hilarious asides—that the track feels more like a stand-up routine than a mean-spirited diss. “Ho” became a local hit in 1999 and exemplified how Luda could take street subject matter and make it tongue-in-cheek fun. Similarly, on “Mouthing Off,” a freestyle-esque track from Incognegro, he rhymes over his friend 4-Ize’s human beatbox, cracking jokes and boasting in outrageous metaphors. “I make niggaz eat dirt and fart dust/Then give you a $80 gift certificate to Pussies-R-Us,” Ludacris spits, piling on juvenile punchlines and shock humor. Lines like that might make a 13-year-old boy cackle—and that’s precisely the point. Even when he’s courting controversy or indulging in raunchy imagery, Ludacris winks at the listener to ensure no one’s taking it too seriously. That witty, almost cartoonish persona would become his trademark in the years to come.

Working with a variety of producers on the album, Ludacris deftly adapts his flow and tone to each soundscape. The original Incognegro tracks feature beats by several Atlanta-based names—Shondrae “Bangladesh” (who handles much of the production), the legendary Organized Noize, and even So So Def mogul Jermaine Dupri—and each brings out a slightly different side of Luda. Over Organized Noize’s soulful, melodic production on “Game Got Switched,” Ludacris sounds right at home alongside the Dungeon Family’s lineage, his flow riding smoothly as he brags about turning the tables in the rap game. When Jermaine Dupri supplies a hard, bass-heavy beat on “Get Off Me” (featuring crunk luminary Pastor Troy), Luda amps up his aggression, matching Troy’s rowdy energy with his own barked threats. And on Bangladesh’s cuts—from the symphonic fanfare of “1st & 10” to the kinetic strip-club romp of “What’s Your Fantasy”—Ludacris proves Shondrae to be his ideal early partner, nimbly dancing between skittering hi-hats and big bass hits. Bangladesh’s contributions were a bit hit-or-miss in terms of complexity, but the cinematic sweep of “1st & 10” and the haunting piano loop of “Stick ’Em Up” are production highlights.

The album announced Ludacris as a fresh new voice with unlimited charisma. Ludacris’s entertainer chops were off the charts. He was, simply put, fun to listen to. Over the next few years, that fun factor would help Ludacris vault from the “Dirty South underground” to the “pop-rap mass market.” In fact, his very next album, 2001’s Word of Mouf, leaned even further into humor and crossover appeal, consciously leaving behind some of the “thuggishness” that had characterized Back for the First Time. But that evolution only underscores how vital Back for the First Time was: on this record, Ludacris proved he could bridge the gap between the streets and the charts. He did it by essentially carrying both sensibilities in his pocket. One moment he’s the class clown of the trap, the next he’s a polished Def Jam hitmaker—and on Back for the First Time, he’s often both at once.

But Ludacris’s energy and wit on the mic remain infectious. His larger-than-life personality shines just as bright in 2025 as it did in 2000, and you can hear his influence in later Southern superstars who combined street sensibilities with humor (from Lil Wayne’s playful metaphors to Big K.R.I.T.’s country pride, and others). Listening back now, certain moments stand out as defining milestones. “What’s Your Fantasy,” with its unabashedly explicit hilarity, still stands as a blueprint for how to make a filthy club track that both underground heads and mainstream audiences can’t resist. “Southern Hospitality,” with its anthemic chants and sticky hook, still compels you to throw your elbows like it’s a Friday night at a packed ATL nightclub. And then there’s “U Got a Problem?”—the opening salvo that introduced Ludacris to the world—which still serves as a mission statement for his career: outrageous, confident, and unapologetically Southern. When Luda calls himself the “ATL-ien intruder” and jams “to Def” while dubbing himself “Slick Dick the Ruler” in that song, you get the whole picture in a few bars: he’s a hip-hop fan student (paying homage to Outkast’s ATLiens and Slick Rick), a consummate jokester, and a force to be reckoned with.

Back for the First Time is a time capsule of Southern hip-hop crossing the threshold into mainstream dominance. The album bridges two eras and audiences: one foot in the raw Dirty South of the late ‘90s, and one foot in the polished, crossover-minded 2000s. Ludacris stands astride that divide with a giant grin, cracking wise and dropping bangers in equal measure. Two decades on, the album’s vitality lives in its balance—the way it captures a moment when an artist didn’t have to choose between the streets and the charts, because he had the talent and personality to conquer both. Ludacris was back for the first time in 2000, and hip-hop hasn’t been the same since.