Anniversaries: Brass by Moor Mother & billy woods

Brass leaves us haunted but not hopeless, awakened to the past and alive to the future, standing at the party’s door with one fist clenched and the other hand reaching beyond the veil.

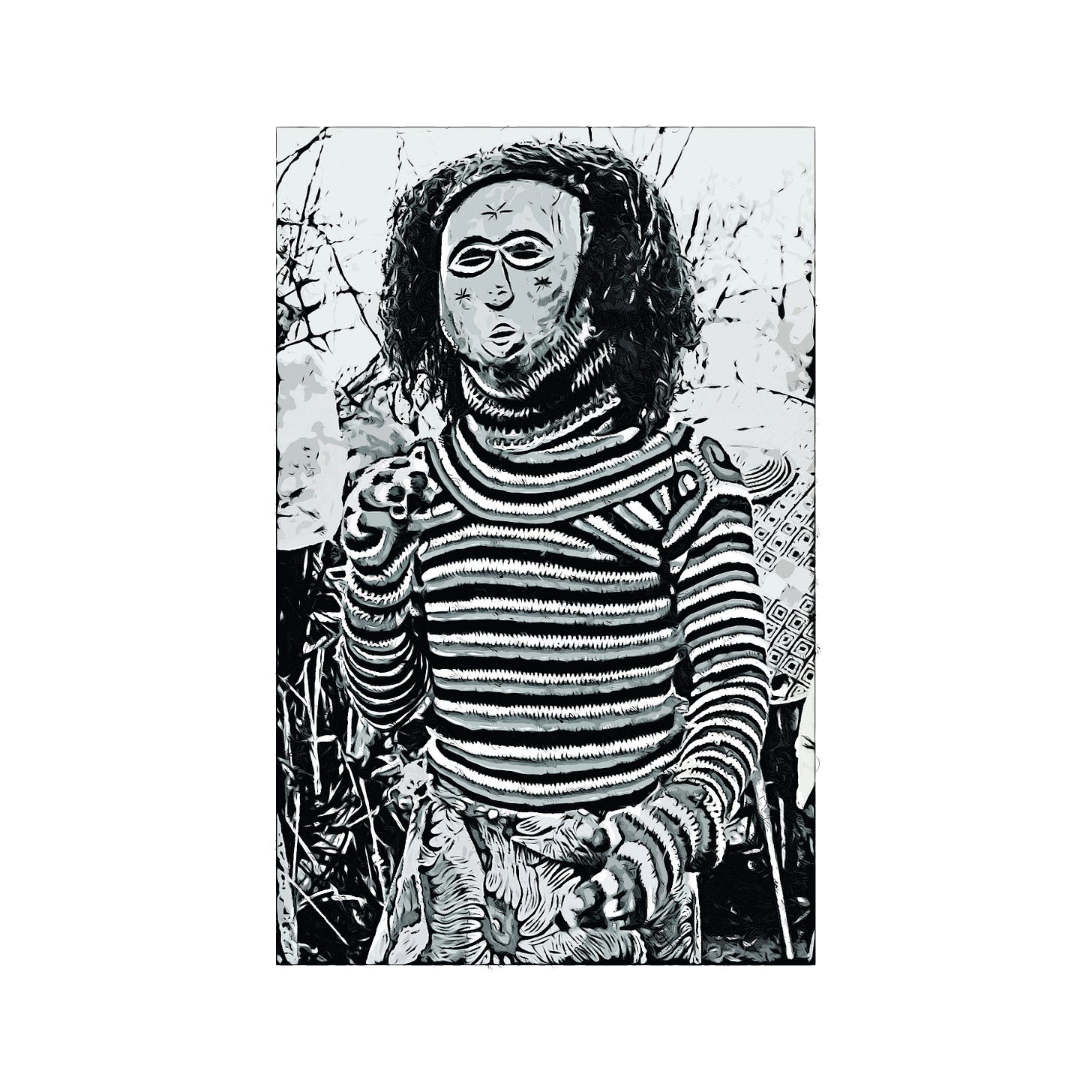

Two figures sift through the debris of history, piecing together relics and star charts. One is an archaeologist, brushing off the dirt to reveal absurd artifacts of empire; the other is a cosmic wanderer, mapping Black futures in constellations. These two visionaries—poet/musician Moor Mother (Camae Ayewa) and rapper billy woods—converge on Brass, a collaborative album that reshapes our very sense of time. Both artists have long treated time as non-linear, refusing the idea that the past and future are sealed off from the present. Moor Mother, co-founder of the Black Quantum Futurism collective, views time travel as a means to recover obscured Black pasts and multiply possible Black futures. Her work evokes cosmic phenomena—black holes, ghostly “hauntings”—to collapse timelines and reveal the illusion of history as straight-line progress. billy woods, for his part, has made a career of excavating history’s rubble: he treats being Black as a form of time travel itself, where the traumas of colonialism and slavery constantly intrude upon the present. In his oblique, often darkly comic narratives, past and present co-exist in a state of cosmic context collapse.

Together, these two time-travelers amplify each other’s visions, wandering through eras and dimensions to recover lost stories and imagine new futures. The project culminates as a bold exercise in Black futurity—one that suggests history’s grip is not unbreakable, even as its wounds still bleed. The genesis lies in a meeting of minds on the 2020 underground rap circuit. Moor Mother had guested on Armand Hammer’s album Shrines earlier that year, trading verses with woods (who is half of the Armand Hammer duo). Their chemistry led to “Furies,” a standalone single for Adult Swim’s music series released in July 2020. Produced by Backwoodz Studioz mainstay Willie Green, “Furies” strikes a deft balance between woods’s grim fables and Moor Mother’s spacey prophecies. Over a hypnotic flip of a Sons of Kemet jazz sample, the two delivered interweaving allegories—a “burning arrow” that both artists would follow into the full album. Though their verses on “Furies” don’t address each other directly, they achieve a parallel harmony, like two oracles tuning their crystal balls to the same frequency.

That uncanny rapport became the guiding thread of Brass, which arrived as a surprise release. The title itself evokes an alloy of disparate metals forged together—a fitting metaphor for the album’s alchemy of styles and ideas. It also nods to brass instruments, whose sharp call is heard throughout the record in sudden bursts of horn and trumpet, heralding both dread and liberation. Willie Green’s production (along with contributions from other experimental beatmakers) gives this record a distinctive sonic palette that tempers the confrontational edge of each artist’s solo work. Both Moor Mother and woods are known for harsh, dissonant sounds in their individual projects—Moor Mother often layering free-jazz cacophony, distorted noise, and spoken word screeds that can feel like confrontations with the listener. woods, too, frequently raps over skeletal, abrasive beats in his underground catalog. On Brass, however, the backdrop is comparatively subdued: a steady fizz of shifting percussion and thick static underpins many tracks, with fuzzy samples warping in and out of focus. Flecks of live instrumentation, from woozy horns to acoustic strings, dot the mix, giving the album an earthy, somber warmth amid the chaos.

On “Mom’s Gold,” for example, a snarl of feedback suddenly tears through the prickly mix, a flash of sonic violence that startles the ear. The track’s minimalist drum loop and muffled piano are momentarily engulfed by a howling distortion—as if a rupture in time itself has opened. “Maroons” offers another textural jolt: what begins as a loping, almost gentle rhythm is soon haunted by a morose trumpet line and a prickly synth wail echoing into the abyss. (The mournful trumpet is played by Aquiles Navarro, Moor Mother’s bandmate from the free-jazz ensemble Irreversible Entanglements, whose presence links the album back to the long tradition of jazz-as-protest.) That soundscape sets the stage for a remarkable interplay of lyrical visions. Neither artist shows much interest in straightforward storytelling or traditional rap braggadocio here. If one had to assign roles, billy woods is the archaeological storyteller, digging through the rubble of history in search of truths, absurdities, and continuities that our society has buried. His delivery is measured, almost professorial at times, but laced with dry wit and grim resignation. Moor Mother is the mystic, a time-traveling griot whose verses feel like vision quests. She’ll hurtle from ancient past to imminent future in a single bar, her tone by turns incantatory, venomous, and slyly playful.

The album is packed with lyrical snapshots that illustrate how woods and Moor Mother approach this temporal warfare. On “Giraffe Hunts,” billy woods delivers one of his most arresting bars: “Traffic stop, I reached for my slave pass slow.” In less than a breath, he collapses centuries—linking a modern-day police encounter with the antebellum reality of “slave passes” that Black people once had to carry as permission to move freely. It’s a gut-punch of a line, evoking the continual haunting of Black life by slavery’s legacy. woods often wields this kind of grim historical irony. On “Rapunzal,” he spits a jaw-dropping aside about economist Alan Greenspan and novelist Ayn Rand in flagrante (“Alan Greenspan fucking Ayn Rand/She came, finished him with her hand”), a scathing little fable that ridicules the unholy marriage of free-market policies and selfish philosophy. His references can be literary or geopolitical: Brass’s lyrics name-check everything from Goya paintings to Idi Amin. Yet even when the specifics fly over a listener’s head, woods’s tone makes the stakes clear—there’s an absurd horror lurking beneath the history we’re taught, and he’s unearthing it piece by piece.

On “Scary Hours,” woods opens with a scene out of a nightmare: a deportation taking place in the futuristic African nation of Wakanda (a pointed Marvel reference). He describes “sickly white men clad in animal skins” anointing themselves African kings, flies swarming on piles of limbs. The grotesque image invokes the 19th-century Berlin Conference—the meeting where European powers carved up Africa—implying that even a Black utopia like Wakanda would be poisoned by colonial legacy. It’s a bleak, audacious bit of satire, casting the beloved fantasy of Black Panther in a harsh new light. woods’s verse climaxes with the refrain, “Inoculate the babies, inoculate the babies,” chanted with urgent nihilism. Then, just when the despair seems absolute, the song’s structure itself enacts a kind of temporal rift: the sky opens up and John Forté (the guest vocalist) swoops in with a burst of harmony—horns and woodwinds swirling—to sing of liberation and escape. In that moment, history’s nightmare gives way to a fleeting vision of freedom. Moor Mother picks up the thread and transforms it into a rallying cry. “Welcome to the party,” she booms over a swell of brass, pointedly channeling the late Brooklyn drill star Pop Smoke. The reference is jarring and brilliant: Pop Smoke’s hedonistic catchphrase is repurposed as a greeting to revolution, as if to say the fight is on—everyone’s invited.

Where woods often peer backward into the abyss, Moor Mother leaps forward and sideways, untethered by chronology. Her verses on BRASS are full of wry temporal mash-ups. On “Rapunzal,” right after woods’s Greenspan/Rand vignette, Moor Mother vaults to an entirely different register: “Through the air like Kobe Bryant/’08 season, the year after Garnett screaming ‘Anything is possible.’” In one cheeky couplet, she references NBA legend Kobe Bryant soaring through the air in 2008, then alludes to Kevin Garnett’s famous championship roar (“Anything is possible!”) from that same era. The line arrives out of nowhere, a pop culture fragment amid ancient ruins, and it works, conveying a sense of Black excellence and triumphal energy, even as it’s couched in irony. Moor Mother delights in these epoch-hopping juxtapositions. On the track “Tiberius,” she pointedly declares, “You can’t imagine a blacker future than me/Forever young, forever in the zone of the one.” It’s a striking mission statement: Moor Mother casts herself as the embodiment of a future Blackness so radical it defies imagination—an Afrofuturist seer who is ageless and completely in the pocket (“in the zone of the one,” a phrase invoking musical oneness and perhaps the funk principle of the One beat).

A remarkable aspect of Brass is that, despite never trading bars directly or engaging in typical duet call-and-response, Moor Mother and billy woods achieve a profound synchronicity. It’s as if they are two wise elders seated at opposite ends of a fire, riffing on the same themes without ever needing to interrupt one another. Throughout the album, they subtly riff on each other’s ideas and motifs. For example, in “The Blues Remembers Everything the Country Forgot,” Moor Mother ends her verse with a searing battle cry, a call-to-arms that channels generations of righteous anger (her exact words seem to summon the spirit of uprisings past). When woods’s turn comes, he responds with a haunting refrain: “We waited and we watched, we waited and we watched.” On “Giraffe Hunts,” a mid-album fever dream, their synergy is even more striking. woods and Moor Mother each unleash a torrent of disjointed imagery: his verse riddled with the ordnance of a warzone—bombs, guns, landmines—and a leering police sergeant leaping out of an American nightmare; her verse populated with slithering cobras, rattlesnakes, and a majestic bison roaming free. On paper, each set of images is vivid in its own right, but they bleed into a surreal panorama.

The album zooms out to view centuries of history and zooms in to magnify a single poignant detail. Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that the only explicit timestamp in the record is also one of its bleakest jokes. On “Rock Cried,” amid dusty drums and echoing chords, billy woods deadpans: “Hydroxychloroquine unpacked and boxed up again.” In one brisk line, he sums up the madness of the year 2020—the false cures and viral misinformation of the COVID-19 pandemic—by referencing the infamous drug that was touted, discarded, and repackaged as hope over and over. Blink, and you’ll miss the reference, but it highlights that entire chaotic year as just another absurd beat in history’s rhythm. Both artists seem to tap into something new together, as the album’s liner notes themselves suggest: Brass is “ethereal and utilitarian, timeless and timeworn—a cast-iron pot propped over a fire in the dark, a tropical beach shimmering with broken glass.” It’s a sound and vision that neither could have fully achieved alone.

The archaeologist vs cosmic wanderer framework really captures how billy woods and Moor Mother operate on different temporal planes. What grabbed me was the "traffic stop, I reached for my slave pass slow" line becuase it compresses 400 years of continuity into a single police interaction, making the abstract historical weight tangible and immediate. The way Brass handles non-linear time reminds me of how certain jazz compositions layer temporal loops where past samples and present improvisation coexist without hierarchy. The comparison to Black Quantum Futurism makes sense too since both reject time as arrow in favor of time as accessible matrix. I actualy listened to this album when it dropped and the sonic restraint surprised me coming from both artists known for abrasive production. Willie Green's approach here feels like he gave them space to be vulnerable without softening the critique, which is a tough balance to hit.