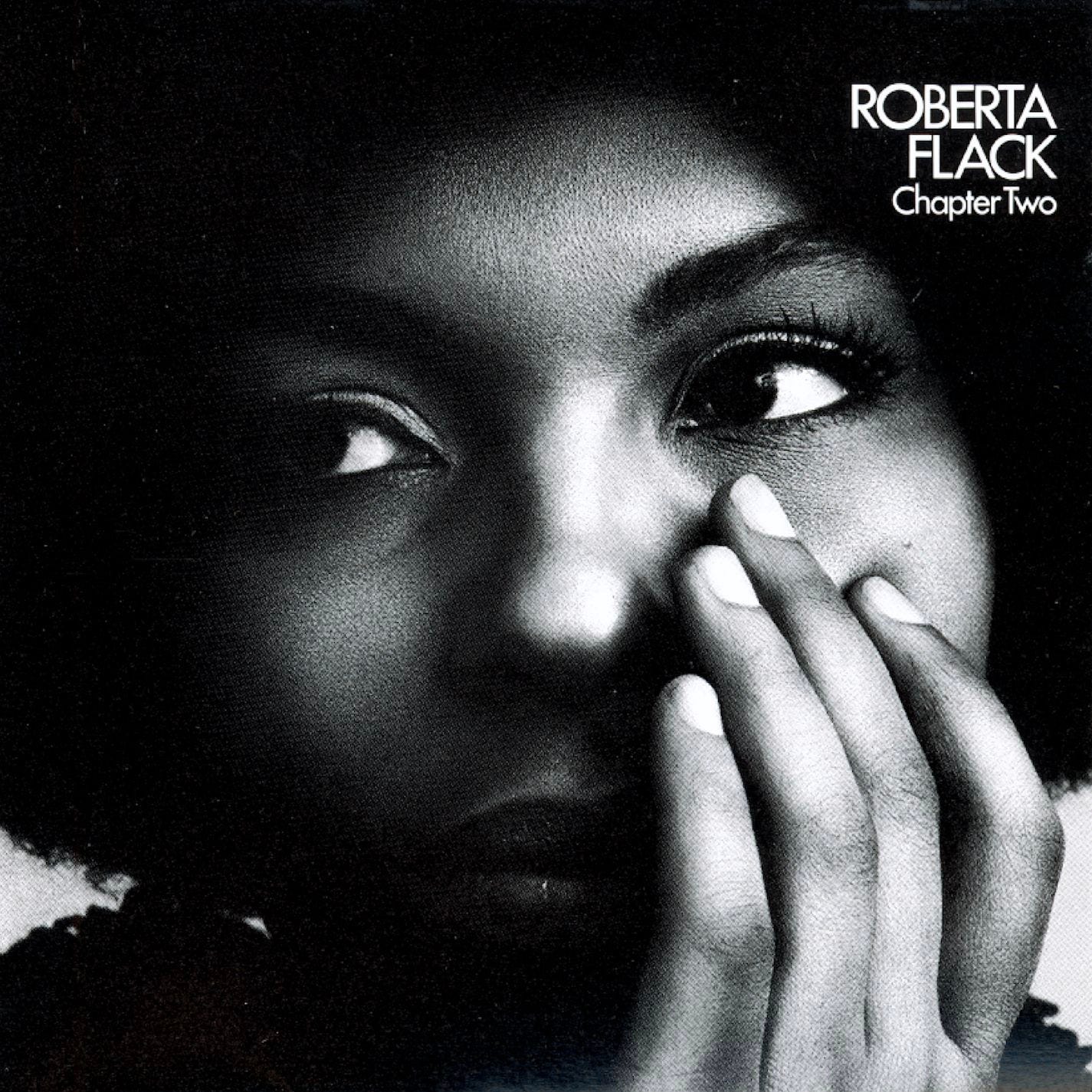

Anniversaries: Chapter Two by Roberta Flack

In Chapter Two, Roberta Flack demonstrates that her artistry has many chapters, each worth exploring, to lean in and listen to a singer who didn’t need to scream to touch your soul.

Roberta Flack opened a new chapter in more ways than one. Her aptly titled sophomore album, Chapter Two, would prove to be the release that elevated her from a little-known jazz hopeful to a bona fide soul and R&B luminary. At the time, some industry skeptics wondered if Flack could move beyond the quiet jazz-club stylings of her debut or repeat the lightning-in-a-bottle success of her breakout ballad “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.” Chapter Two answered them resoundingly. It showcased an artist of immense versatility, a classically trained pianist with a soft, compelling, alluring voice who could“convincingly switch gears to express the full spectrum of emotions, from enderness and sorrow, bitterness and protest, longing and defiance. Those who had pigeonhole Flack as a one-hit wonder or a strictly jazz-oriented singer were forced to reconsider, as Chapter Two unfolded like an ambitious suite of Black music in eight varied movements.

Unlike many soul divas of the era, Flack didn’t need to shout to make herself heard. Her power was in subtlety. Her voice on Chapter Two is often hushed and confessional, drawing the listener in close. She had honed this intimate style singing in Washington, D.C. clubs, fusing folk, blues, and jazz influences, and here she applied it to an expansive selection of songs. The album’s eight tracks span an almost audacious range of genres—“soul, rock, folk, Broadway, pop, and protest”—a “stylistic smorgasbord” that Flack navigates with characteristic grace and thoughtfulness. In lesser hands, such a grab-bag might have felt disjointed, but Flack’s gentle approach is the unifying thread. She once insisted she never thought of music as “soul” but rather “soul-ful,” and in Chapter Two, she indeed rejects rigid labels. What emerges is a portrait of an artist in transition, stretching beyond the jazz-folk refinement of her debut and blossoming into a major voice in early ‘70s R&B.

The opening track, “Reverend Lee,” immediately signals that Flack is not interested in playing it safe. It’s a song ripe with lusty imagery and ironic humor, delivered in Flack’s earthy alto that is equal parts sensual and sly. With Charles Rainey’s bass bubbling underneath and an eight-piece horn section stirring up a storm of gospel flare, “Reverend Lee” feels like a mini dramatic play. She brings a hint of sympathy to the “devil’s daughter” temptress even as she pokes fun at the straight-laced preacher for his faltering piety. “Do What You Gotta Do,” a soulful ballad penned by Jimmy Webb, finds Flack in the role of the self-sacrificing lover who must let her man follow his path. The arrangement is understated, featuring Flack’s piano, gentle bass, and brushed drums at first, giving her room to distill every ounce of feeling from the lyrics. In her hands, this song of parting becomes both an act of unconditional love and a subtle rebuke. “So you just do what you gotta do, my wild sweet love,” she croons with a tender resolve, “Though it may mean that I’ll never kiss those sweet lips again… Come on back and see me when you can.”

On “Until It’s Time for You to Go,” Flack again stretches a familiar song into a personal statement. Buffy Sainte-Marie’s folk original was a concise two-and-a-half minutes; Flack’s version is nearly twice as long, an intimate slow-burn that luxuriates in the last moments of a doomed love affair. She begins it at almost a whisper, accompanied only by the delicate filigree of her piano and Terry Plumeri’s bass. “Don’t ask forever of me—love me now,” she pleads, repeating the line like a mantra as if prolonging the present can stave off the inevitable goodbye. Flack’s ability to inhabit others’ songs reaches a high point with “Just Like a Woman.” By 1970, Bob Dylan’s bittersweet classic had been covered by many, but Roberta Flack was the first solo female artist to tackle it on record. Rather than simply imitating Dylan’s phrasing, Flack transforms the song from the inside out, offering what feels like the woman’s point of view on a story originally told by a man. Over a gentle, gospel-tinged arrangement, she delivers the famous chorus lines with a twist: “I take just like a woman, and I make love just like a woman, and I ache just like a woman,” she sings, “and I break up like a little girl.” That slight lyrical variation, “break up” instead of Dylan’s “break,” is crucial. By using the first person, Flack aligns herself with the subject of the song, imbuing it with autobiographical resonance. Her ribbons and bows, symbols of feminine pride, are displayed alongside her “problems,” hinting that her identity as a woman (and implicitly as a Black woman) is bound up with the pain she carries

Flack turns the Everly Brothers’ pop standard “Let It Be Me” into something unmistakably her own, adding a layer of church-like reverence; her voice flows in gentle waves, as if each phrase were a prayer. “Gone Away,” which opens Side Two, is a soul ballad co-written and arranged by Flack’s friend and frequent collaborator Donny Hathaway (along with Curtis Mayfield and Leroy Hutson). Ever the chameleon, Flack then takes on a Broadway showstopper: “The Impossible Dream” from Man of La Mancha. In lesser hands, this might have been an odd detour—the song’s theatrical bombast can easily tip into schmaltz. Flack, though, approaches it with disarming sincerity and a simmering intensity. She begins gently, letting the famous melody (“To dream the impossible dream, to fight the unbeatable foe…”) roll out of her like a quiet declaration. In 1970, as a Black woman forging her path in a music industry often reluctant to categorize her broad style, she was living an impossible dream of sorts, daring to be all that she was, genre boundaries be damned. Her performance turns the potentially overblown anthem into a personal mission statement.

For the album’s finale, Roberta Flack chose a quietly devastating protest song. “Business Goes On as Usual” is a somber anti-war ballad (written by Fred Hellerman and Fran Minkoff) that hadn’t gained much attention since its mid-’60s folk origins. Flack’s interpretation ensured it would not be forgotten. Over a sparse arrangement, she assumes the persona of a narrator observing with bitter irony how life at home continues amid the sacrifices of the Vietnam War. Business goes on as usual, the song notes, people shop, work, and live their daily lives, “except that my brother is dead,” comes the gut-punch refrain. Flack sings these lines in muted, almost matter-of-fact tones, which only heightens their impact. Her restraint here is harrowing: she doesn’t scream or wail; she lets the horrifying truth speak for itself, voice hushed with grief and disbelief. Without raising her volume, she conveys quiet anger at the injustice and profound despair at the loss. We are left to sit with the heavy silence and to appreciate the bold emotional rollercoaster Roberta Flack has guided us through on this album.

In roughly 38 minutes, Chapter Two navigates love and lust, longing and loss, and hope and despair. It’s not a concept album in the traditional sense, but there is an inner logic to its progression; the record feels like a tour of the human heart, with Roberta Flack as the soft-spoken but soul-baring narrator. Though the album’s stylistic diversity is striking (and perhaps risky for its time), Flack’s artistic vision holds it together. Most importantly, this proved Roberta Flack’s versatility and depth beyond any doubt. It answered the skeptics who thought her too jazz, too quiet, or too dependent on other people’s songs. With this record, Flack made clear that interpreting a song is an art unto itself, one at which she was a singular master. She wrote her own rules for what a Black woman artist in the 1970s could sound like, where at once soulful and jazzy, pop-savvy and protest-conscious, sensuous and spiritual.

Although it may not be as widely remembered as First Take or Killing Me Softly, Chapter Two is a landmark of Black music in the early 1970s, a rich and immersive album that captures Roberta Flack coming into her own. Its songs are full of the intense emotions that would come to define her presence as a singer. There is an almost cinematic quality to the album; each track is like a scene where Flack, the consummate storyteller, brings a new character or mood to life. She can make you feel the flush of forbidden desire in one moment and the cold ache of loss in the next, all with that elegant, unforced delivery. In Chapter Two, Roberta Flack demonstrates that her artistry has many chapters, each worth exploring. It’s an album that invited the world to slow down and “dig the slowness,” to lean in and really listen to a singer who didn’t need to scream to touch your soul. And over fifty years later, its spell remains as compelling as ever, proof that Roberta Flack’s quiet fire could burn as intensely as any of her louder peers, on her distinctive terms.