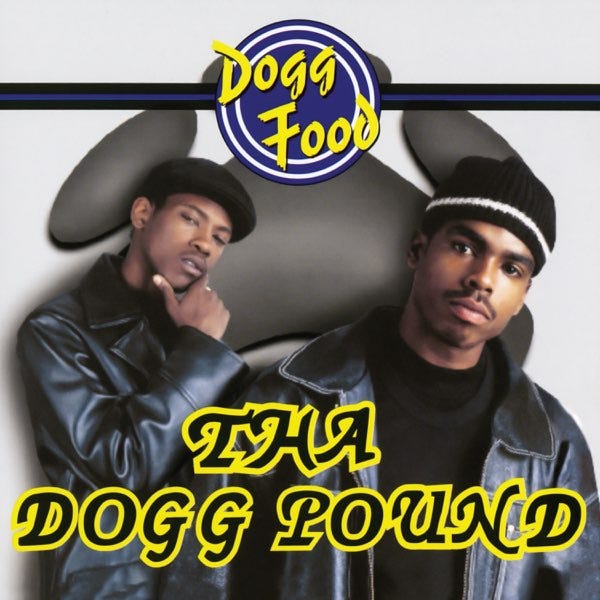

Anniversaries: Dogg Food by Tha Dogg Pound

When considered alongside the two West Coast classics, Dogg Food is an homage and transition. It pays respect to the G‑funk architecture, yet it marks a divisive entry in the West Coast canon.

Delmar “Daz Dillinger” Arnaud and Ricardo “Kurupt” Brown were already fixtures on Dr. Dre’s The Chronic and Snoop Doggy Dogg’s Doggystyle when their own record became the flashpoint for a moral panic. In early 1995, a faction of U.S. senators and activists used gangsta rap as a proxy for everything wrong with popular culture. Conservative firebrands like Bob Dole and C. Delores Tucker denounced the new West Coast sound from Capitol Hill, and pressure reached the boardrooms of entertainment conglomerates. Time Warner executives responded by announcing that they would sell back the company’s 50 percent stake in Interscope Records—the distribution partner for Suge Knight’s Death Row label. Their decision to disassociate from Interscope—even at the cost of hundreds of millions of dollars in sales—reflected the fear of being seen as peddling music filled with profanity, misogyny, and violence. The immediate target of their ire was Dogg Food, the debut album by the duo known as Tha Dogg Pound, which had already been pushed from August to Halloween. Daz and Kurupt refused to tone down their rhymes despite being told they had time to soften the record’s edges. The label’s CEO, Suge Knight, promised that the group “will have their day on the charts.” At street level, those pronouncements meant more anticipation than outrage.

The corporate dance that followed was messy. Warner’s contract with Interscope prevented the parent company from blocking an album outright. Michael Fuchs, the chairman of Warner Music, quietly explored ways to get out of the crossfire while politicians attacked the label’s gangsta acts. Interscope weighed its options: release Dogg Food and further inflame opponents, or delay the album and risk losing credibility with the streets. The solution was both business and streetwise. Interscope sold back its half to co‑founders Jimmy Iovine and Ted Field and teamed up with the independent powerhouse Priority Records to distribute the disc. The move kept the album in the pipeline while appeasing Time Warner’s shareholders. When Dogg Food finally arrived on October 31 1995, consumers ignored the admonitions of Dole and Tucker and sent it straight to the top of the Billboard 200. SoundScan logged roughly 278,000 copies sold in the week ending November 5, almost twice as many as its nearest competitor. The controversy effectively served as free marketing.

There is a sonic reason why the record connected so quickly. By 1995, the G‑funk style Dre had perfected on The Chronic had become the dominant sound of West Coast hip‑hop. G‑funk is built on slow, hypnotic grooves between 90 and 100 BPM, live‑sounding drums, a deep bass line, and a high‑pitched portamento synthesizer lead. Producers often layered soulful keyboard melodies and multi‑layered synthesizer lines over interpolations of Parliament‑Funkadelic’s seventies funk. Rap flows on these tracks often adopt a slurred or lazy cadence, punctuated by background female vocal moans. This formula gave Dre and Snoop’s early releases a languid, summery feel that belied the ferocity of the lyrics. Daz and Kurupt built Dogg Food on that same blueprint. Dr. Dre did not oversee production this time—he mixed the record and lent his name—but Daz produced almost every track. The result is a record that often feels like a third sequel to The Chronic, following Doggystyle and the Murder Was the Case soundtrack.

Seventeen tracks (plus skits) sprawl across the album. The roster reads like a family reunion: Snoop Dogg, Nate Dogg, Michel’le, the Lady of Rage, Tray Deee, and Mr. Malik drop by. The singles “New York, New York,” “Respect,” and “Let’s Play House” were rolled out over several months, but the album is meant to be consumed as a whole. The opener, “Dogg Pound Gangstaz,” sets the mood immediately. A synth whines over a rubbery bass line while Kurupt brags that his rhymes are “as potent as pipebombs,” and Daz follows by threatening to “serve your ass when you headin’ to school.” The interplay between the two MCs is part of the record’s charm: Kurupt is the technician, flipping syllables and internal rhymes with surgical precision, while Daz barks his couplets in a blunt, almost conversational style. The label’s blueprint—deep rumbling bass, soul‑sampling loops, cheap, whiny synthesizers, and shrieking R&B vocals—pervades the album. Yet Daz brings his own twist: his production tends to be bouncier and sunnier than Dre’s, with rigid, funky drum patterns and sparkly piano keys. On the mic, he delivers with a commanding tone that contrasts nicely with Kurupt’s nimble flow.

“Respect” follows with an insistent bass groove and a reggae‑tinged hook courtesy of Prince Ital Joe. Dr. Dre’s mixing makes the kick drums crack and the synths breathe; every hi‑hat lands on the off‑beat, leaving space for the rappers to stretch out. The chorus demands respect not only from peers but also from the corporate suits who attempted to shelve the record. Kurupt’s verses ride the beat effortlessly, using internal rhymes (“potent as pipebombs,” “microphones all set to unload”) to mimic the loops swirling beneath him, while Daz growls about serving up bodies. The tension between discipline and brutality echoes West Coast street politics: the duo celebrates survival while acknowledging constant threats.

The most notorious track, “New York, New York,” sits at the center of Dogg Food’s legacy. Produced by DJ Pooh and mixed by Dre, the song flips a sample of Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five’s 1983 song of the same name. Kurupt opens with a sneer, “The barbaric, versatile/You no kin to me, so how the nigga you inherit my style,” planting his flag over the East Coast classic. The beat features a woozy synth and swaggering drums that evoke a slow‑motion trunk‑rattle. When the group traveled to New York City to shoot the video, tensions from the East Coast–West Coast feud boiled over. The video, set in Brooklyn and Manhattan, was filmed after New Yorkers felt disrespected by West Coast artists filming in their city. In response, Snoop and the Dogg Pound filmed scenes kicking down a skyscraper facade, and Capone‑N‑Noreaga, Mobb Deep, and Tragedy Khadafi answered with the diss track “L.A., L.A.” Within days, the media had transformed a playful homage into another salvo in the coast‑war narrative. For the artists, it was simply a chance to flex. Kurupt runs laps around the beat with multisyllabic patterns while Snoop’s drawl slides across the chorus, turning a simple phrase—“New York, New York”—into an anthem and a provocation.

Other songs explore familiar West Coast themes with varying degrees of imagination. “Smooth,” one of three tracks not produced by Daz, rides a DJ Pooh beat built from a growling synth‑bass and shimmering keys. Snoop and Jewell croon the hook while Kurupt steals the show with tongue‑twisting couplets. “Cyco‑Lic‑No” pairs Daz and Kurupt with Mr. Malik over a stuttering beat; the rappers trade threats and one‑liners, and Malik’s closing verse nearly steals the show. “Ridin’, Slipin’ and Slidin’” is a day‑in‑the‑life narrative: Daz recounts neighborhood survival tactics while South Sentrelle’s background vocals soften the edges. “Big Pimpin 2” is essentially a pimp sermon delivered over a breezy, space‑age groove. “Let’s Play House” features Michel’le and Nate Dogg, whose silky hooks turn a straightforward sex narrative into a nostalgic slow jam. Throughout the album, the duo pepper their rhymes with West Coast slang, weed references, and deviant sex acts, but what stays is the musical chemistry. Even the interludes—mock radio station W‑Balls bits with comedian Ricky Harris playing a sleazy DJ—feel like part of a world rather than filler.

The consistency can be a double‑edged sword. Dogg Food often feels like a polished replay of earlier Death Row triumphs. The Washington Post noted at the time that the duo’s variation on what had become a stale formula was less sample‑driven and instead focused on the formidable verbal flow of Daz and Kurupt. The Baltimore Sun heard a freshness in the growling synth‑bass of “Smooth” and the tropical pulse of “Big Pimpin 2.” Trouser Press, meanwhile, dismissed the album as “a low‑key, unambitious and only mildly imaginative replay of Doggystyle, rolling over familiar G‑funk terrain.” All three assessments are accurate in their own way. Daz sticks close to Dre’s blueprint, but his bouncier drum patterns and melodic flourishes keep the tracks from being mere carbon copies. Kurupt’s wordplay brings new energy; his internal rhymes and breath control elevate songs that could have been formulaic. At the same time, it can feel like the safe bet rather than the great leap forward. The explicit subject matter—guns, sex, and weed—rarely veers into social commentary, which may explain why many critics filed it under conservative homage.

Dogg Food was only the fifth project to emerge from Death Row, following The Chronic, Doggystyle, and the Above the Rim and Murder Was the Case soundtracks. Those records had sold millions and defined the West Coast aesthetic. At the time of Dogg Food’s recording, the label was also nurturing 2Pac’s All Eyez on Me, which would expand Dre’s sonic palette. In that context, Daz and Kurupt’s decision to stick with the proven formula looks less like timidity and more like preservation. Daz had only recently been elevated from sidekick to head producer; Dogg Food allowed him to prove he could carry an album without Dre, and Dre’s minimal involvement made that statement louder. According to RapReviews, the duo engineered Death Row’s blueprint “to great results,” and Daz’s bouncier, sunnier tracks would mold the West Coast sound for years to come. The commercial payoff was immediate: the album debuted at number one on both the Billboard 200 and Top R&B/Hip‑Hop Albums charts and was later certified double platinum.

Beyond chart positions, the record’s legacy lies in its snapshots of mid‑’90s Los Angeles. Kurupt’s verses are littered with references to Long Beach corners and Compton blocks. When he raps about “Ridin’, slippin’ and slidin’ through the city,” he evokes low‑rider cruises and nighttime drives past neon liquor stores. Daz’s gruff admonitions recall the lethal pragmatism of the streets—protect your own, move in silence, never show weakness. On “Reality,” he outlines the consequences of betrayal over a beat co‑produced by Emanuel Dean; the rhythm is minimal, letting Daz’s paranoia fill the spaces between snare hits. The track “Some Bomb Azz Pussy” flips Zapp’s talkbox funk into an ode to hedonism; Kurupt’s comedic delivery prevents the song from descending into outright misogyny. In “A Doggz Day Afternoon,” Snoop Dogg and Nate Dogg join the duo for a breezy two‑minute cameo that feels like an intermission at a backyard barbecue. These vignettes anchor the album in its time and place.

The skits, often overlooked, also contribute to the narrative. Kevin “Slow Jammin’” James and comedian Ricky Harris voice DJs on the fictional radio station W‑Balls, dropping lecherous monologues over smutty R&B loops. In one interlude, a phone-line caller confesses sins, only to be met with laughter; in another, a preacher hawks salvation while malt liquor ads play in the background. These moments satirize corporate hypocrisy—mocking the same moralizing politicians who tried to suppress the album. They also provide breathing room between the hard‑hitting tracks, making the album feel like a drive down the 405 with the radio dialed to a pirate station that only plays Death Row artists.

When considered alongside The Chronic and Doggystyle, Dogg Food can be read as both homage and transition. It pays respect to Dre’s G‑funk architecture, yet it marks the point at which the architect ceded the studio to his understudies. Daz would become Death Row’s primary in‑house producer, shaping the beats on All Eyez on Me and later on Tha Dogg Pound’s follow‑ups. Kurupt’s intricate flows foreshadowed the lyrical dexterity that would permeate West Coast rap in the late 1990s. The album’s conservative adherence to the G‑funk blueprint may seem like a missed opportunity, but it also preserved a sound that would soon fade as Dre and others pivoted toward darker, more minimalist production. In that sense, Dogg Food is a closing chapter and a time capsule. It captures the moment when Death Row still felt like an unstoppable family before inner turmoil, legal battles, and violence unraveled the label.

Dogg Food remains a divisive entry in the West Coast canon. Its defenders hear a near‑perfect distillation of G‑funk, executed by hungry artists eager to prove they could hold their own without Dr. Dre. Its detractors hear a competent but safe record that repeats the moves of its predecessors. What cannot be denied is that the album’s journey from corporate boardrooms to platinum plaques exposed the fault lines between art and commerce. Conservative critics attempted to suppress it, but contractual clauses and independent distributors ensured that it reached stores. Once there, listeners voted with their wallets, turning the controversy into a marketing bonanza. Whether heard as conservative homage or missed opportunity, Dogg Food remains a crucial chapter in the story of G‑funk and a reminder of the cultural battles that hip‑hop has navigated on its way to the mainstream.