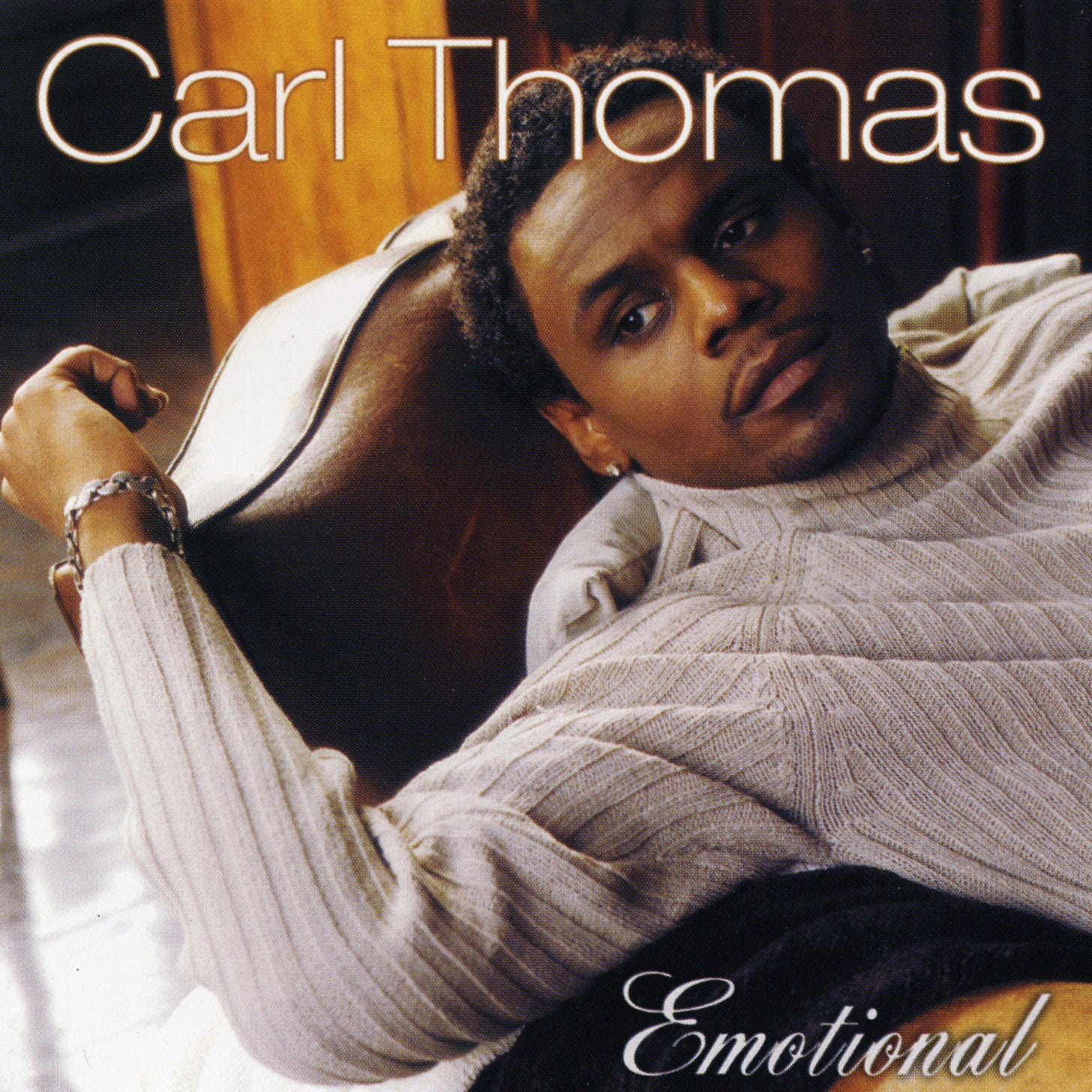

Anniversaries: Emotional by Carl Thomas

Carl Thomas wasn’t an overnight creation. Emotional purposefully leaves us in a suspended state—aware of unresolved tensions, still resonating with lingering confessions.

In the closing years of the 1990s, Bad Boy Records had come to embody a peculiar mixture of swagger, gloss, and soulful spectacle—its roster leaning heavily on hip-hop-inflected bravado and crossover polish. The label’s sonic identity was in flux by 1999–2000: the echoes of the “golden era” Bad Boy swagger were still audible, yet the dawn of “millennial R&B” demanded a softer frontier of confession, restraint, and emotional inwardness. Emotional arrives as a delicate pivot, pressed between that swagger-first ethos and a new craving for vulnerability.

From that vantage, Carl Thomas’s signing was no casual gambit. As Bad Boy’s first major solo male R&B signee in this transitional era, he embodied a latent risk: could the label accommodate a gentler, soul-rooted confessor among its brash roster? His entry bridged two imperatives—public spectacle and private truth. His early guestings (on remixes, hooks, feature spots) already spoke to the label’s modus operandi: he was part of the Bad Boy machine, but he carried a quieter weight. In industry terms, it inherited a high level of expectation. The label was keen to maintain its cultural leverage into the new century, and to do so through a voice that would feel both brand‑adjacent and deeply personal. Thus Thomas was positioned at a hinge: part of Bad Boy’s afterglow (its aesthetic, its marketing muscle) and yet in dialogue with a newer R&B sensibility that leaned less on bravura and more on intimate interiority.

Carl Thomas wasn’t an overnight creation. Before Bad Boy Records, before New York studios and music-video gloss, he was a quiet presence in Chicago’s late-night musical undercurrent. Born in Aurora, Illinois, he sharpened his voice away from the spotlight, performing at open-mic nights, church halls, and dim-lit clubs where sincerity mattered more than spectacle. In these rooms—often sparsely attended—Thomas found something essential: the power of his voice to connect through understatement. It was in these smaller, unassuming spaces that his songwriting took form. Thomas composed carefully—lines that reflected inner truths rather than catchy refrains. The early songs he carried to New York weren’t polished pop anthems; they were melodic confessions, delicate but candid. It was precisely this emotional transparency that caught the ear of industry insiders—producers, A&Rs, and eventually, Puff Daddy himself—who sensed the deeper value behind the restraint.

His move to New York was itself understated: there was no immediate buzz, no explosive debut. Thomas’s voice became a known yet largely invisible asset, appearing subtly on remixes and hooks for labelmates, whispered rather than shouted, a complementary tone against Bad Boy’s louder personas. Yet even in these minor appearances, something distinct emerged. Producers quickly noticed his vocal texture—warm, slightly grainy, naturally vulnerable—possessed the kind of intimacy rarely captured on records aiming for mass appeal. Those early sessions—the quiet hours spent demoing songs late at night in New York studios—formed the bedrock of what would become Emotional. Producers such as Mario Winans, Deric “D-Dot” Angelettie, and Mike City understood how to frame Thomas’s voice to highlight its subtlety rather than overwhelm it. This deliberate approach—patient, introspective, devoid of instant gratification—was more aligned with ‘70s quiet-storm classics than contemporary pop-R&B. It was here, in this careful calibration of voice, space, and storytelling, that the quiet confessor from Chicago became the emotional anchor of Bad Boy’s turn into the millennium.

At first glance, Emotional appears straightforward: an album about love, longing, regret, and quiet reconciliation. Yet its narrative runs deeper, functioning not merely as a collection of songs but as a carefully paced intimacy arc. Its sequence intentionally guides listeners from surface-level romance to inner vulnerability. Beginning with the introspective “Intro,” the record signals a deliberate departure from Bad Boy’s more spectacle-driven projects. Immediately, Thomas is audible in quieter tones—there are no triumphant openings, no grand entrances. Instead, the listener finds him already mid-reflection, thoughts unfinished, suspended.

The early placement of the “Anything” interlude and “My Valentine” isn’t accidental; these tracks lay out the emotional terrain. They capture initial optimism and romance in their earliest forms—moments suffused with possibility, though gently shadowed by doubt. As the album unfolds, the mood shifts inward: relationships fray, misunderstandings arise, and Thomas’s voice deepens into confession. The sooner we reach “Emotional,” the album’s titular centerpiece, the sooner they’ve traveled beyond surface affection into more complicated territory. Here, emotion is no longer simple joy or sadness but a complex, bittersweet tangle of desire, regret, and frustration.

Thomas uses songs as emotional waypoints—small narrative markers that sketch out the arc of personal experience without explicitly narrating it. For instance, “Cadillac Rap” offers a momentary break from the intensity, but even this brief detour carries undertones of escapism, nostalgia for simpler times, and a wish to pause the emotional upheaval. This becomes clear that the album isn’t offering a neat resolution. Rather, Emotional purposefully leaves listeners in a suspended state—aware of unresolved tensions that still resonate with lingering confessions. This structure ensures the album’s intimacy is authentic, mirroring the uncertainties and half-resolved truths that define real emotional life. In short, the album’s careful sequencing and thematic interlocking aren’t merely artistic flourishes—they’re an essential frame, turning Emotional into something quietly profound: a sustained meditation on vulnerability itself.

From the start, Emotional was born into a tension: the friction between commercial ambition and private grace. Bad Boy Records in 2000 was not a label accustomed to hushed intimacy; its legacy was built on hits, videos, spectacle, cross‑genre hooks, and star power. To house a project so inward-focused demanded both faith and risk—faith in a voice unadorned, risk that it might not land with mass consumption. For Carl Thomas, this meant navigating label pressures, marketing expectations, and his own refusal to surrender the subtleties his songs required. One veteran producer once told Thomas that radio demanded louder hooks, bigger choruses, more gloss. At moments in the making of Emotional, the urge to lean into those demands tugged at the edges of the project: instrumentation might swell, vocal layers might thicken, ad‑libs might press harder. But Thomas and his collaborators often pushed back, cutting back when elements threatened to dominate. It insists that confessional R&B can breathe, not be suffocated under its own ambition.

Emotional doesn’t rest on broad emotional generalities—it anchors itself in specifics. Carl Thomas’s songwriting relies heavily on quiet, observational detail, each lyric working as a delicate pivot, capable of shifting the album’s emotional gravity. On the title track, “Emotional,” Thomas leverages an intelligent sample (Sting’s “Shape of My Heart”) as a framing device—but his delivery ensures it never feels merely ornamental. His lyricism moves beyond conventional romantic regret; it’s a careful articulation of inner conflict, guilt, and self-awareness. “I knew you when I had a friend/Very deeply love lived within” reveals how his restraint magnifies emotional stakes. Every melodic decision here—notes bent gently downward, hesitation in vocal rhythm—amplifies a subtle yet palpable sorrow, shifting the song from radio-friendly smoothness into something deeper, quieter, more complicated.

“I Wish,” perhaps the album’s best-known track, again demonstrates Thomas’s melodic nuance and lyrical sincerity. The verses unfold almost conversationally, each phrase breaking with natural speech rhythms, pausing mid-line to mimic the hesitation of private thought. He’s quietly negotiating between memory and regret—longing and resolution. “I wish I never met her at all” isn’t one of the most memorable R&B hooks in recent memory. It’s an internal admission, a reluctant truth he’s finally forced himself to voice aloud. Thomas’s melody stays close, never reaching for the expected climactic note, deliberately withholding release. By keeping tension unresolved, the song invites listeners into the intimacy of unfinished emotion, making it clear that real vulnerability rarely arrives neatly packaged or resolved.

On deep cuts such as “Summer Rain” (not really a deep cut) and “Giving You All My Love,” Thomas subtly expands the emotional palette, varying his melodic choices to deepen the album’s complexity. “Summer Rain,” with its atmospheric layers, positions Thomas’s voice softly against a melodic line built from whispers and suggestions rather than overt declaration. Here, emotion isn’t expressed through dramatic vocal runs but through quiet modulation—his voice mirroring the gradual, accumulating sensations of a gentle storm. Conversely, “Giving You All My Love” works by measured intensity: Thomas remains tightly controlled throughout, but small shifts in delivery—how he lightly drags the ends of lines or lets particular words dissolve into silence—elevate it from simple affirmation into something more layered, thoughtful, and carefully uncertain.

Throughout the album, each lyrical and melodic pivot isn’t just a stylistic flourish—these moments define Emotional as a masterclass in subtle emotional storytelling. Carl Thomas quietly demonstrates emotional depth, line by line, note by note, capturing complexity in shades of quiet introspection. Even as his debut album was being shaped, the tension between commercial ambition and inward honesty pulsed quietly beneath the surface. The expectations placed upon Carl Thomas were heavy: he was Bad Boy’s hope to stake a gentler, more heart‑led claim in male R&B, while still operating within a star system that prized gloss, singles, and first-week sales. That push and pull—between vulnerability and market imperatives—became one of the album’s silent conflicts.

In interviews, Thomas has recalled how Puff Daddy (it’s still fuck him) sometimes urged acceleration, pushing for hit material or faster tempo, while Thomas himself resisted overproducing or overshadowing his own voice. This friction shows in the record’s uneven spaces—moments where restraint almost gives way to label desire, but then pulls back again. It is precisely in those edges that Emotional sustains its moral backbone: a project that refuses to fully surrender to the market’s demands. Upon release, it did not initially land as a mass spectacle event—its power was quieter, more internal. Fans responded more to small gestures than to big ones. Over time, that quiet gravity became part of the album’s endurance. Its initial reception was respectful yet reserved, but its resonance deepened over many rounds of listens.

Its long tail influence—on neo‑soul, on confessional male R&B in the 2000s—derives from precisely that mode of restraint. Artists paying homage to Emotional often cite “I Wish” or the title track as touchstones, not because of chart numbers, but because they offered a way to express heartbreak without declaiming it, to show fragility without collapsing into melodrama. The album becomes a blueprint: how to carry a song softly, not shout it, so the listener can inhabit it rather than merely consume it. And yet, even after two decades, the tension remains. Emotional is a slow burn of a success and a quiet sorrow—successful in endurance, but always in dialogue with what might have been if more polish, more promotion, more “hits,” had been the priority. In that continual friction lies its vitality: not in resolving the conflict, but in living with it, so that each listen feels like a test of patience, memory, and emotional bravery.

Thomas’s subsequent projects, released in a different musical climate, often echo this early tension. At times, he leaned harder into production; at others, he retreated into minimalism, always contending with the demands of commercial viability and artistic fidelity. Emotional remains both a high watermark of what was achieved and a benchmark against which his later work would be measured. The unspoken challenge remains: can one sustain such inward power across changing industry currents? The aftermath isn’t tidy. Emotional never solved the tension between market demands and internal truth—but perhaps it never was meant to. Its endurance is a living negotiation, neither victory nor failure, but ongoing. When we discuss this record, what stays with us is not triumph or regret, but the careful haunting of its unresolved spaces. In that tension lies its moral weight.