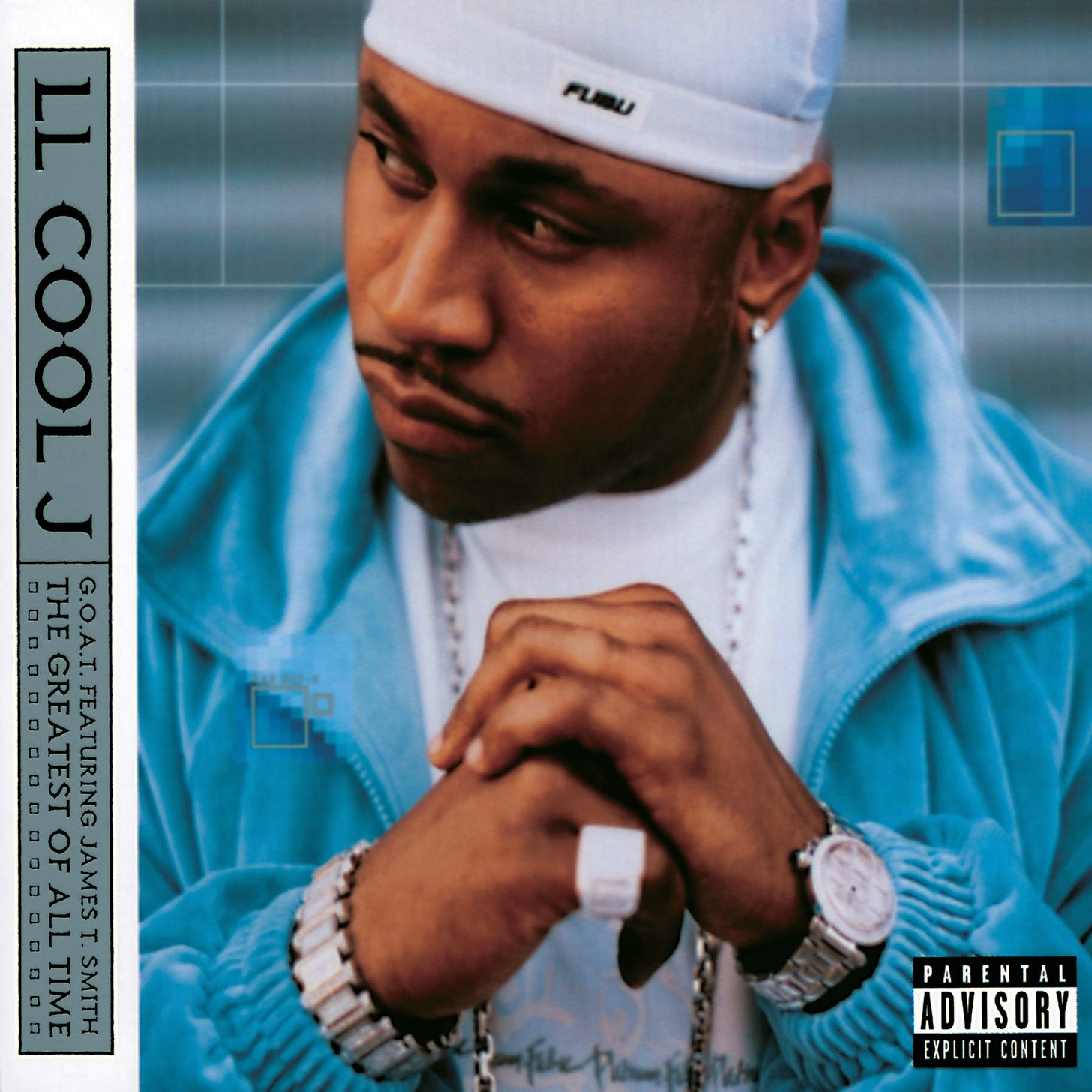

Anniversaries: G.O.A.T. (Featuring James T. Smith: The Greatest of All Time) by LL Cool J

G.O.A.T. didn’t prove the case outright, but it kept him in the conversation—licking his lips, flexing his expertise, and daring anyone to call it a comeback.

In the fall of 2000, hip-hop icon LL Cool J boldly crowned himself the “Greatest of All Time.” Draped in diamonds and a sweat-defying fur despite the sweltering New York heat, James Todd Smith exuded the audacious confidence of a rap veteran who had nothing left to prove, yet was intent on proving it anyway. His eighth album, G.O.A.T. (Greatest of All Time), arrived with a title as weighty as the platinum chains around his neck. More than two decades later, the question remains whether LL Cool J truly lived up to that promise, and how his music’s evolution—or stubborn consistency—fares in hindsight.

LL Cool J’s claim to GOAT status did not emerge from a vacuum. By 2000, he was already a pioneer with a 15-year career, dating back to the mid-’80s when his freestyling bravado and radio-ready beats helped bring hip-hop from the block to the mainstream. As a teenager on Radio, LL introduced himself as a “street-smart b-boy with a lover-man streak,” coupling battle rhymes and charisma in a way few had before. His early hits showcased a fluid, nimble flow that astonished listeners used to more rudimentary rap cadences. Tracks like “Rock the Bells” were technical triumphs, and even LL’s first foray into rap balladry, “I Need Love” (1987), displayed an ambitious range for the genre. By the late ’80s, LL’s persona oscillated between cocksure battler and ladies’ man, a jack-of-all-trades skill set that sometimes left hardcore fans wanting more grit.

On Walking With a Panther, LL reveled in playful seduction and material excess, notably on the cheeky single “I’m That Type of Guy,” where he brags about sneaking into a rival’s home to romance the man’s girlfriend. Over a funky, minimalist beat, LL grinned through lines like “You’re the type of guy that gets suspicious, I’m the type of guy that says, ‘The pudding is delicious’,” flaunting his role as the sly older seducer. It was braggadocio with a wink, the self-proclaimed Ladies Love Cool James indulging in comical machismo. Yet some found Panther’s formula wearing thin. The album’s tales of “faceless gold-diggers” and “don’t-leave-your-girl-‘round-me” vengefulness felt formulaic. Even the infectious single “Going Back to Cali”—all moody bassline and black-and-white cool—was more memorable for its vibe than any lyrical depth (LL famously murmurs “I don’t think so” about Cali’s bikinied beauties, as if even his desires were fickle).

By 1990, facing backlash that he’d gone too pop, LL came roaring back with Mama Said Knock You Out. On that title track, he snarled, “Don’t call it a comeback, I've been here for years,” a line now etched in hip-hop lore. Over Marley Marl’s hard-hitting production, LL’s battle-ready ferocity and quotable punchlines reasserted his credibility. The album proved LL could still “unleash pure energy like he did back in the day” when properly motivated. The ensuing years saw him constantly toggling between two personas: the rough-edged rapper hungry for respect and the smooth-talking charmer hungry for love. Early ‘90s efforts like 14 Shots to the Dome tried to lean into hardcore trends, while 1995’s Mr. Smith spun off sexy R&B-laced hits (“Doin’ It,” “Hey Lover”) that expanded his appeal with female audiences. Through it all, LL’s obsessions stayed consistent, where the braggadocio and seduction, even as the soundscapes around him changed.

By the late ‘90s, however, hip-hop’s landscape had shifted dramatically. A new generation of MCs with more complex flows and diverse subject matter was on the rise. LL’s 1997 album Phenomenon received a lukewarm reception, with many doubting whether the veteran still “had it” in the era of DMX and Wu-Tang Clan. A high-profile feud with rising lyricist Canibus in 1997 (sparked on LL’s own posse cut “4, 3, 2, 1”) left LL looking defensive and arguably outdated, despite his blistering diss track “The Ripper Strikes Back.” It was amid this climate that LL Cool J prepared his next move—a bold declaration that he was not ready to be put out to pasture by the new school.

In September 2000, LL Cool J responded to the doubters by dropping G.O.A.T. (Featuring James T. Smith: The Greatest of All Time). Even the title was a flex—LL took an acronym used by boxing legend Muhammad Ali (and borrowed from streetballer Earl “The Goat” Manigault) and planted his flag firmly atop it. In hip-hop vernacular, “GOAT” was not yet the cliché it is today; LL arguably introduced the term to the rap world in a mainstream way. It was a statement as much as an album title: after 16 years in the game, LL was claiming the belt. Crucially, G.O.A.T. became LL’s first album to reach #1 on the Billboard 200, proof of his enduring star power. But commercial success aside, the central question remains: did the music itself justify the self-anointment?

The album’s production and collaborations suggest LL was aiming to cover all bases. On G.O.A.T., he is at once the street-savvy battle rapper trading bars with hardcore elite, and the suave lothario whispering sweet (or explicitly dirty) nothings to the ladies. It’s a duality LL had long mastered, and here it’s executed with mixed results. The record opens with the Rockwilder-produced single “Imagine That,” a sultry head-nodder explicitly crafted for the late-night slow jam format that made “Doin’ It” a hit five years earlier. Over a spare, bouncy beat and LeShaun’s breathy coos, LL purrs X-rated come-ons. Yet the track is potent but familiar. By 2000, the boundaries of sexual expression in rap had pushed far past innuendo, and LL strove to keep up—perhaps too eagerly. On “Imagine That,” he paints a Penthouse-worthy scenario involving champagne and photocopiers that aims to titillate but lands as tacky. In one wince-inducing boast, he describes dousing his privates in Cristal and making two-dimensional Xeroxes of his lover’s anatomy—a line that might have provoked shock or laughter in 2000 but now registers as cringe. For an artist once celebrated for clever wordplay and charisma, especially coming off the fire-ass intro, resorting to over-the-top sexual braggadocio without a wink of self-awareness felt like chasing shock value rather than leading it.

Besides the song finding LL firmly in freak mode again, the album quickly pivots to remind us of his street credentials. “Back Where I Belong,” driven by a Vada Nobles beat, has LL staking his claim as a battle cat once more. Over ominous bass hits and a guest verse from Ja Rule (then one of New York’s rising stars), LL addresses his old nemesis Canibus. But instead of a lyrical clinic, LL brags about behind-the-scenes power plays like sabotaging Canibus’s deal with Wyclef Jean. It’s an odd bit of O.G. moralizing on an album otherwise focused on fun and floss; airing out industry gossip made LL seem more petty than powerful.

The record steadies when LL plays to his strengths while embracing the new generation. One highlight is “Fuhgidabowdit,” a posse cut with DMX, Redman, and Method Man. The Trackmasters-produced beat knocks with a glossy East Coast-meets-club sheen. LL comes in boisterous—“You say I’m souped up? Well soup’s good food”—only for that corny line to get mercilessly outshined once Redman and Meth grab the mic. Their verses crackle with effortless cool, making LL’s contribution feel stiff by comparison. Still, LL deserves credit for inviting hungry MCs and not ducking the contrast. On “U Can’t Fuck With Me,” he goes toe-to-toe with West Coast stalwarts Snoop Dogg, Xzibit, and Jayo Felony. Bolstered by a pounding DJ Scratch beat, LL raises his intensity to match his guests, delivering gritty bars with enough Queens swagger to hold his own. The track is a later-album gem—one where LL spits with fire and sounds as invigorated as ever.

Likewise, “Queens Is,” featuring Prodigy of Mobb Deep, taps into LL’s hometown pride. Over Havoc’s eerie production, LL and Prodigy trade verses celebrating the rough edges of Queens. Here, LL’s veteran presence doesn’t feel outdated; it feels earned. With a fierce gleam, he rides the beat smoothly and shows genuine chemistry with Prodigy, reminding listeners that this is the same kid from Farmers Boulevard who once rocked the bells and boomed his system. Tracks like these fulfill the album’s promise far better than the trend-chasing club joints.

Elsewhere, G.O.A.T. stumbles. LL’s attempt at a Timbaland-esque track, “Take It Off,” comes off as mimicry—an unremarkable dance jam that plays like a “Vivrant Thing” knockoff. Meanwhile, the female-friendly R&B collaborations land unevenly. “Hello,” a duet with Amil, pairs LL’s smooth talk with a Diana Ross sample and glossy Scratch production. But the lovers-trading-flirty-verses conceit feels half-baked. “You and Me” fares better, thanks to Kelly Price’s powerhouse vocals elevating the hook. Over a warm mid-tempo groove, LL drops affectionate rhymes aimed at domestic bliss, a pleasant throwback to the “Around the Way Girl” side of his catalog. One can’t shake the feeling that G.O.A.T. was a calculated portfolio of “LL Cool J, all sides on display.” The pacing flips between modes almost dutifully: rugged street bangers like “Homicide” balanced against slick lover-man joints like “This Is Us” with Carl Thomas. It’s the classic LL formula, but in execution, it spreads itself thin. He was acutely aware of the generational divide and trying to straddle it, resulting in an album at odds with itself—proudly old-school in ethos yet draped in millennium-era gloss, full of bravado yet intermittently defensive about its legacy.

How does LL’s approach compare to his peers? Consider A Tribe Called Quest’s Q-Tip—another Queens native who started in the late ‘80s rapping about girls and flings. On “Bonita Applebum,” he playfully cooed over a woman’s “38-24-37” figure. Years later, his lyrics had shifted toward spirituality, connection, and social thought. LL’s arc, by contrast, stayed mostly static. Even on G.O.A.T., at age 32, he stuck to teenage scripts. Outside the battle boasts, the content centers on seduction, luxury, and swagger. That fur coat in summer wasn’t just fashion; it was a symbol of his unwavering allegiance to hip-hop extravagance. This raises a dichotomy: consistency versus complacency. On one hand, hearing LL still “talking trash” and “reeling off endlessly inventive boasts” carries a certain comfort. On the other, the same routines can read as tone-deaf. As hip-hop moved toward self-awareness and maturity, LL often doubled down on the forever-playboy persona. The recurring theme of the older man guiding a younger woman in love or lust aged poorly, especially in an era more attuned to power dynamics and consent. Lines once heard as confident or funny now risk caricature.

So, did G.O.A.T. earn its title? The album’s debut at #1 and eventual Gold status proved LL’s staying power. When he was in his element, dropping battle rhymes with veteran bite or leaning into Queens-bred charm, the claim didn’t feel outlandish. But stacked against his own catalog, it doesn’t eclipse Mama Said Knock You Out, Radio, or even Mr. Smith. Trying to be all things left it uneven. At its worst, he sounded like an ‘80s great bending awkwardly toward Ruff Ryders trends. At its best, he still knocked out challengers with charisma and force.

In hindsight, the real victory of G.O.A.T. was cultural. The acronym itself became global vernacular; much of the world learned the word “GOAT” in part because LL Cool J branded it. That impact gives the record a legacy beyond its tracks. Musically, it’s a mixed bag—beats that bang, boasts that land, but also play-it-safe repetition. In 2025’s lens, the album shows an artist grappling with legacy rather than transcending it. LL embodied the spirit of the “Greatest of All Time” in posture, longevity, and cultural imprint, even if the album didn’t seal the claim. It’s a good album from one of rap’s greats, but not the greatest album of all time. And perhaps that’s enough: LL Cool J’s career is bigger than a single record title. G.O.A.T. didn’t prove the case outright, but it kept him in the conversation—licking his lips, flexing his expertise, and daring anyone to call it a comeback.