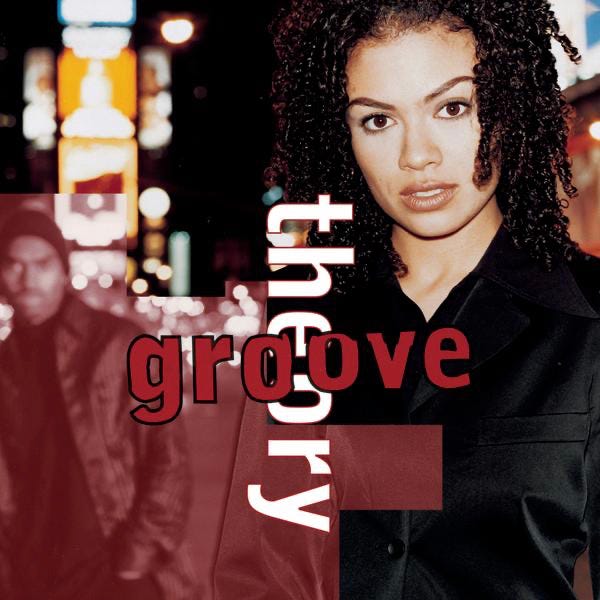

Anniversaries: Groove Theory by Groove Theory

Unlike the explicit world‑building of their peers, Groove Theory plants its imagery in everyday moments—commutes, stoops, first kisses.

The mid‑1990s were saturated with R&B: Mariah Carey, Toni Braxton and Whitney Houston were beating each other to the top of the Hot 100 with melismatic ballads, Boyz II Men and Soul for Real swooned through bittersweet harmonies, TLC crept while Jodeci feened and freaked, and artists such as D’Angelo and Mary J. Blige were wading into 1970s soul to forge smoky new hybrids. The sound of new jack swing and hip‑hop soul was ascendant. Bryce Wilson, a Queens teenager who had rapped with Mantronix, took this flood as a challenge. In his parents’ bathroom, he began building songs, poring over Donny Hathaway chord changes and Teddy Riley rhythms. Having wearied of Mantronix’s frantic beats and the expectation that he mimic his hero Riley, he rejected the dance floor entirely, trading battle raps for a producer’s chair and building tracks that moved slower, deeper—almost in secret. The name he chose for his new project, Groove Theory, reflected that ambition: music as an idea as much as a physical experience. They arrived in the autumn of 1995 looking like a refutation.

When Wilson encountered Amel Larrieux through music publisher Karen Durant, he found a partner whose sensibilities aligned with his own. Larrieux, a high‑school graduate steeped in poetry, jazz, and Sade Adu, was an assistant at Rondor Music when Durant suggested she write to one of Wilson’s melodies. Raised in Philadelphia and the West Village’s artistic enclave, Westbeth, she scribbled maudlin poems and admired writers like Maya Angelou and Toni Morrison. As a teenager, she sang along to Jimi Hendrix and Joni Mitchell, turning her poetry into lyrics and cultivating a “silky softness” that stood apart from the gospel‑trained belters then dominating R&B. She respected Sade’s ability to be “refined or raw, but never street” and wanted to tell stories without resorting to histrionics. Wilson and Larrieux met in his home studio, which doubled as a bathroom. Larrieux brought lyrics she had initially been written for Trey Lorenz, and the pair captured them over Wilson’s minimal beat. Wilson was mesmerized by how Larrieux’s melodies seemed to approach from an entirely different angle. Her breathy voice and literate lines meshed with his spare programming, and Groove Theory coalesced in that humid bathroom.

The duo’s contrarian impulse extended beyond their personal chemistry. Where producers like Jermaine Dupri or Babyface piled on samples, Wilson refused them entirely. He had been told to make songs that sounded like new jack swing, yet he was listening to Stevie Wonder’s Extension of a Man and wanted to evoke that album’s wide emotional palette. Groove Theory’s songs were built from a marriage of programmed beats and live instrumentation that felt both contemporary and nostalgic. Wilson’s drum programming thudded like a Jeep rolling over potholes, but session players—especially bassist and guitarist Darryl Brown—brought warmth. Brown is credited on bass, guitar, and keyboards across the record, and Larrieux’s liner notes call him the duo’s third member.

On “Come Home,” his rubbery bassline and shimmering guitar chords cushion Wilson’s thunderous drums; he punctuates the track with subtle fills, underscoring Larrieux’s plea that a partner leave the street life and come home. “Ride” and “Hey U,” Groove Theory’s flirtations with G‑funk, are shaped by Brown’s deft hand. The rhythm of “Ride” suggests hydraulics without replicating Dr. Dre’s showy low‑rider; Brown’s bass glides rather than bounces, and the guitar chords nod to funk without overtly quoting Parliament. Over this, Larrieux sings about “going for a ride” with a lover, an invitation that is literal rather than lascivious. Where Adina Howard purred “do you wanna ride” with undisguised intent or Snoop bragged about switches on his ‘64 Impala, Larrieux describes slipping into a car and turning the key. “Hey U” slows the tempo further, Brown’s bassline moving like a walk home after the club, his guitar echoing the loneliness of Larrieux’s encounter with an ex. She stretches the embarrassment of bumping into a former lover into a breathy coo, prolonging the wordless refrain “hey you” until resignation becomes a melody.

Throughout the album, Wilson’s refusal to sample becomes a calling card. Listeners often insist that “Tell Me” borrows the bassline from the Mary Jane Girls’ 1983 hit “All Night Long,” but the resemblance is a sonic mirage. Wilson told journalists he was “trying to kill new jack swing,” an approach motivated by his frustration with labels that demanded he replicate the genre. He built all of the grooves from scratch, with Brown and other players layering chords and basslines until the songs felt as though they had always existed. The drums of “10 Minute High” may remind listeners of A Tribe Called Quest’s “Check the Rhime,” and the vibe of “Time Flies” evokes Shelly Manne’s jazz standard “Infinity,” yet there are no direct lifts. The groove is theoretical: Wilson’s beats evoke memories without sampling them.

Larrieux’s lyrics move in step with this production ethos. She refuses to be a vixen; her songs are thoughtful, often melancholy stories about addiction, regret, and self‑love. On “10 Minute High,” which opens the album, she sketches a teenage girl chasing a brief euphoria, addicted to a drug that provides respite from grim circumstances. Her delivery is cool, her voice tracing the melody with precise consonants instead of runs. Unlike Mary J. Blige’s raw confessions or Mariah Carey’s athletic melismas, Larrieux’s restraint invites listeners to lean closer. “Boy at the Window” bookends the album with another childhood tragedy, this time a boy idolizing an absent father; his pain unfolds over minor‑key chords and crisp snare hits. Larrieux observes rather than sermonizes, and her tone seldom rises above a whisper. Some will argue that this restraint sometimes undersells the gravity of her narratives, leaving the characters so tragic “they don’t feel real.” Yet there is an argument to be made that her understatement is itself an aesthetic choice. Larrieux once said she wanted young women to know they didn’t have to be “this sexy goddess” and could instead have a love for music. Her refusal to perform pain theatrically aligns with that ethos. When she repeats “Your day is coming, though it seems far/Things will be clear when you love who you are” on “Keep Tryin’,” the motivational message could have been syrupy; her measured phrasing renders it stoic and personal.

Contrasting Groove Theory with other syncretic experiments of the mid‑’90s reveals why the duo’s frictionless blend of styles never generated the same mythos. Meshell Ndegeocello’s Plantation Lullabies fused funk and spoken word with a political edge; Sade’s Love Deluxe wrapped melancholy around jazzy minimalism; D’Angelo’s Brown Sugar channeled Marvin Gaye and his own raw sensuality. Groove Theory’s music, by comparison, is unashamedly cool and smooth. Kearse describes the album as a vacated club—“warm blue light encased in darkness,” Soul II Soul’s Caron Wheeler replaced by emptiness. There is no friction between influences because Wilson and Larrieux deliberately avoid the edges where genres collide. Even their cover of Todd Rundgren’s “Hello It’s Me,” modeled after the Isley Brothers’ 1974 arrangement, flows so seamlessly into the set that it could be mistaken for a Larrieux original. Wilson’s beats may recall jazz‑rap producers Q‑Tip and DJ Premier, but the pair eschew the tension that defines those producers’ work. This frictionless quality can make Groove Theory’s world feel less vivid than the self‑contained universes of Brown Sugar or Love Deluxe. Where D’Angelo’s songs conjure smoke‑filled rooms and Sade’s conjure rain‑soaked windows, Groove Theory’s songs are lit by candles; the heat is gentle, the shadows are soft.

“Tell Me,” the song that thrust Groove Theory into popular consciousness, details their contrarian stance and their accidental accessibility. Larrieux had written the lyrics for Trey Lorenz’s solo project; Wilson and Larrieux recorded the track with the intention of giving it away to British quartet Rhythm N Bass. Their demo sat on the shelf until Epic Records insisted they include it on their album. The song’s supple bassline, slick percussion, and soft keys blur confession and confrontation. “I’ve been doing my own thing/Love has always had a way of having bad timing” Larrieux sings at the top, setting up an admonition that doubles as an invitation: “tell me if you want me to.” She sounds unbothered, almost nonchalant, yet the rhythm and melody are so inviting that listeners lean in. Despite their initial reluctance, “Tell Me” climbed to No. 5 on the Billboard Hot 100 and No. 3 on the R&B chart. Its popularity hinged on the very qualities Wilson and Larrieux downplayed: a hook bright enough for radio, a bassline reminiscent of an earlier hit, and a chorus easy to chant. Wilson later confessed he was embarrassed by how easy it was to make, but its success financed the album and gave the duo their moment in mainstream light.

Most of the album’s other songs eschew such immediacy. “Time Flies” pairs jazz‑inflected chords with reflections on the passage of time. Larrieux sings, “Here we are/Look how long it’s been/We’ve come far… Now we’re grown/On our own/Everybody’s moving on,” capturing the melancholy of aging friends drifting apart. “Baby Luv” is a bouncy ode to Larrieux’s newborn daughter; its exuberance nearly tips into bubblegum, yet a remix dialed back the pop elements for those who found it too cute. “Good 2 Me,” Larrieux’s favorite track, blends a raw hip‑hop beat with smooth soul, conjuring the aura of A Tribe Called Quest’s The Low End Theory. The song imagines a lover who is “good to me” despite the world’s chaos, and the beat seems to strut down a city block. Across these songs, Wilson paces the album like a rap record; there are interludes and instrumentals, but the sequencing emphasizes groove over narrative arcs. The only true ballad is “Angel,” where Larrieux’s voice lifts over a slow groove to ask for protection, a moment of spiritual respite.

Epic Records had trouble marketing the group; publicist La’Verne Perry‑Kennedy recalled that imaging Amel was difficult because she refused to dress like the “video hoochies” of the era. She ended up performing in Prada suits that matched the group’s cool aesthetic. The label sent the duo to hair salons and mall appearances, which Wilson jokingly resented. As modestly dressed Muslims with a jazz‑infused sound, they sat at odds with the hyper‑sexualized R&B market. Nevertheless, the duo toured with D’Angelo and the Fugees in 1996, hinting at an alternate history in which they might have carved out a niche within the burgeoning neo‑soul movement.

That history never materialized. Wilson and Larrieux experienced creative differences and drifted apart. Larrieux married Wilson’s friend Laru Larrieux, converted to Islam, and gave birth to their daughter, Sky. She later contributed to Sweetback (Sade’s backing band) and launched a solo career; her debut, Infinite Possibilities, arrived in 2000, followed by releases on her own label, Blisslife Records. Wilson, meanwhile, produced Toni Braxton’s “You’re Makin’ Me High” and Mary J. Blige’s “Get to Know You Better,” built a second career as an actor, and attempted to revive Groove Theory with singer Makeda Davis. The resulting sophomore album, The Answer, was shelved after the single “Never Enough” (from the Love Jones soundtrack) failed to make an impact. Fans still ask Wilson and Larrieux whether a real reunion will occur, but the duo’s brief existence only adds to their myth.

Groove Theory’s footprint is small but persistent. The duo’s hushed sensuality and hard beats can be traced, albeit faintly, to later acts like Little Dragon or The xx, but the line is more imagined than direct. Their music’s influence is perhaps most evident in the acknowledgements of artists who cite Larrieux as an inspiration: Pitchfork notes that Solange, Hikaru Utada, and Kelela have all praised her. Solange’s A Seat at the Table and When I Get Home share Larrieux’s interest in interiority and restraint, while Kelela’s intimate vocal runs and electro‑soul production echo Groove Theory’s refusal to choose between R&B and electronic textures. Yet these connections live mostly in the minds of musicians and fans. Mainstream retrospectives of neo‑soul often bypass Groove Theory entirely, moving from D’Angelo and Erykah Badu directly to Jill Scott.

Unlike the explicit world‑building of their peers, Groove Theory plants its imagery in everyday moments—commutes, stoops, first kisses. Its refusal to chase trends or sample obvious classics gives the album a timeless quality; the songs breathe because they are not anchored to 1995’s sonic signposts. The record persists in memory rather than in canonical lists. It lives on dusty mixtapes, late‑night radio slots, and small clubs where DJs drop “Tell Me” to make couples sway.