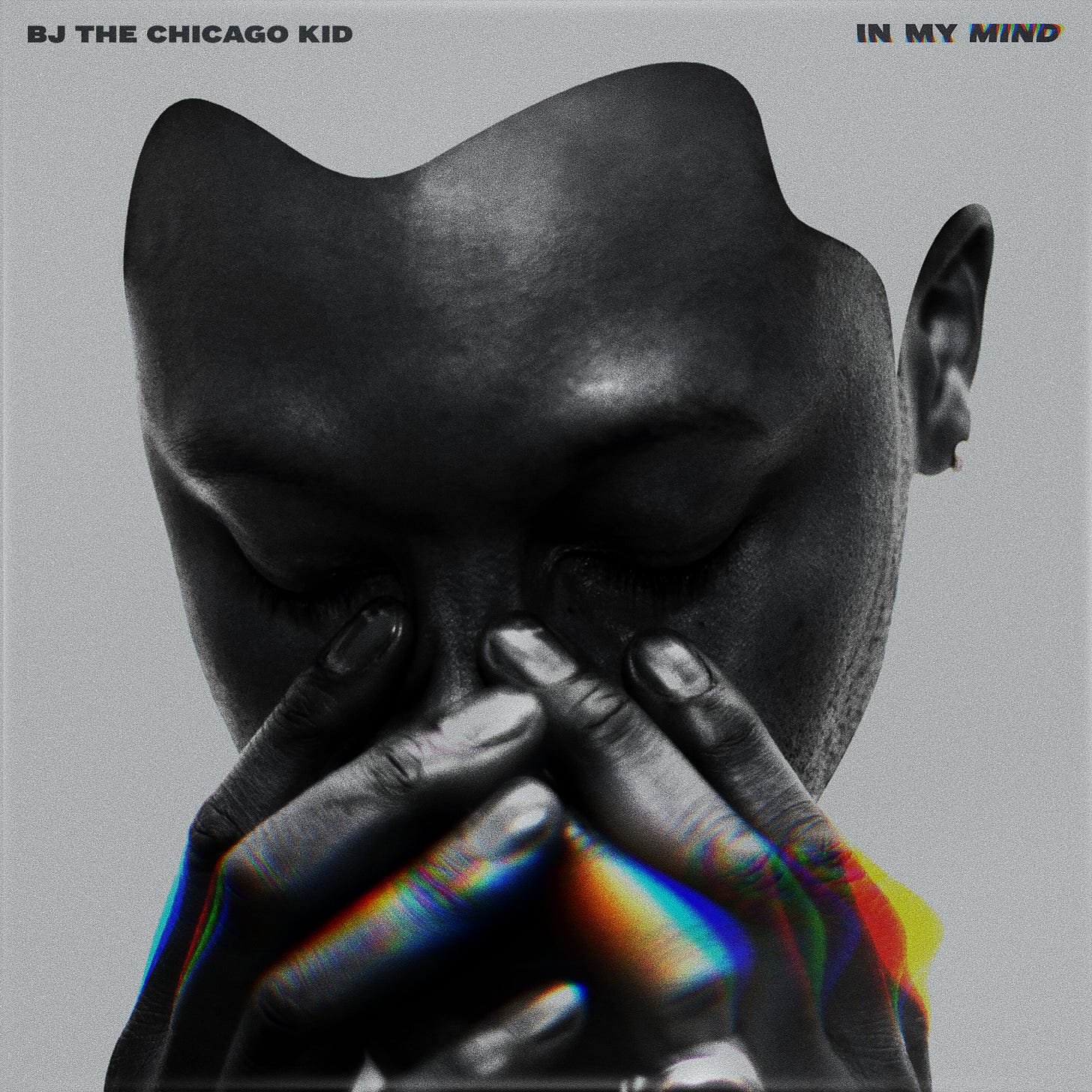

Anniversaries: In My Mind by BJ the Chicago Kid

BJ the Chicago Kid spent years in other people’s sessions before Motown gave him a debut. In My Mind proved the voice was ready even if the industry wasn’t.

Bryan James Sledge spent his twenties singing in rooms that belonged to somebody else. He wrote for gospel acts and lent his voice to sessions where no liner note would carry his name past the first pressing. He sang backup for Mary Mary, contributed to Stevie Wonder’s A Time to Love, and placed songs with Shirley Caesar, including “A City Called Heaven,” co-written with his brother Aaron. None of this was apprenticeship in the usual sense. Sledge was not learning. He was earning, and waiting, and building the kind of vocal control that only comes from having to fit inside someone else’s arrangement night after night without disturbing the furniture.

By the time he surfaced as BJ the Chicago Kid, the discipline was audible but the opportunity kept sliding. Motown signed him in 2012 and quickly issued a single from his self-released Pineapple Now-Laters, a gesture that felt more like a handshake than a door thrown open. For the next several years, the label’s newest R&B singer was most visible as a guest on other people’s major releases. He showed up on ScHoolboy Q’s Oxymoron, Dr. Dre’s Compton, and Marsha Ambrosius’ Late Nights & Early Mornings. The same year he co-wrote “A City Called Heaven” with Aaron for Caesar, he appeared on Kendrick Lamar’s “Faith.” He was everywhere and nowhere simultaneously, a voice people trusted enough to borrow but not enough to schedule.

Almost four years after the Motown deal and more than a decade after Sledge started placing songs professionally, In My Mind arrived. The gap between signing and debuting would be unremarkable for a pop act groomed from scratch, but Sledge was already a grown man with a catalog of uncredited work and a reputation that preceded the product. Motown had released a string of headlining singles in the interim, each one paired with a rapper, each one solid, and each one commercially invisible. The label seemed unsure whether BJ could sell on his own name. The album, when it finally materialized, inherited that uncertainty in its bones.

The record sticks of the friction it generates between two competing claims. Sledge sings like a man who grew up testifying in church and moved into secular romance without ever fully leaving the sanctuary. His falsetto bends the way a choir tenor’s does when the spirit hits, but his subject matter keeps pulling him toward Saturday night. He talks to women with a tenderness that sounds earned rather than performed. On “Woman’s World,” he commits to a kind of deference that most male R&B men of his generation would have coded as weakness. He does not qualify the pledge. He does not sneak in a caveat about his own needs. The track asks nothing back, and the melody stays warm without turning pleading. Three cuts later he is flirting with an edge, admitting appetite with the same directness, and the album never pretends the two postures cancel each other out. Sledge holds them both and lets the contradiction sit.

The featured players complicate this further, and deliberately. Kendrick Lamar appears on “The New Cupid,” and his verse lands with the gravitational pull that any Lamar feature carried in 2015 and 2016. The question for BJ is not whether his own performance holds up beside a rapper operating at that altitude. It does. He wraps around the hook with an assurance that refuses to compete with Lamar’s intensity. The real snag is subtler. Lamar’s presence converts the track into an event, and events have a way of swallowing the host. BJ spends much of In My Mind trying to prove he can sustain a full album’s worth of mood on his own terms, and every featured verse both sharpens his argument and undermines it. He needs the collaborators to generate commercial interest. He resents the implication that he cannot carry the load by himself. Both things are legible in how the album sequences its biggest names.

Chance the Rapper arrives on “Church,” a cut that should be simple but ends up doing something slippery. The beat has gospel warmth without gospel architecture. Chance’s verse brings his usual mixture of joy and moral inventory, and BJ matches it with a delivery that sits right at the boundary between praise and seduction. The word “church” gets repeated until it stops functioning as a noun and starts working as a feeling, a haze between gratitude and hunger. BJ does not moralize on the track. He does not separate the sacred from the profane and assign each its proper seat. He lets them share a pew. Chance’s contribution gives “Church” permission to be spiritually fluent without being pious, but it also means that the album’s most direct moment about faith requires a co-sign from a rapper whose public persona was already synonymous with positive Christianity. BJ, who came from actual church labor, still needs a translator.

On “The Resume,” Big K.R.I.T. raps with a regional heft and a bluntness that BJ’s smoother phrasing does not always reach for. K.R.I.T. sounds like a man who drives his own car to the session. The contrast is generative. Sledge is meticulous, careful about where each syllable falls, conscious of how much vibrato to release at the end of a line. K.R.I.T. does not share that fastidiousness, and the collision pushes BJ into a register of masculine honesty that his solo ballads sometimes polish out of existence. “The Resume” benefits from it, but the improvement comes from an outside hand toughening a posture that BJ, left on his own, might have kept too clean.

The line everyone remembers from “The New Cupid” is a diagnosis more than a boast. “Cupid’s too busy in the club, at the bar, rollin’ up,” BJ sings, and the accusation is aimed squarely at his own generation of R&B men who abandoned courtship for lifestyle branding. He appoints himself the replacement, the one willing to do the old work of wooing and vulnerability in an era that had largely moved past both. The claim is bold, and BJ delivers it without hedging. But the irony sits right there in the tracklist. He is declaring himself the last honest lover on a record that still needs three rappers to get anyone’s attention. The self-appointed Cupid cannot get his arrows to land without borrowed quivers.

That abrasion does more good than harm. When BJ has a track to himself, truly to himself, the temperature shifts in ways the features cannot replicate. “Turnin’ Me Up” strips the production to a keyboard pulse and a bass line that moves with the patience of a slow dance at the end of the night. His phrasing does not try to impress. He lets notes decay naturally, does not stack ad-libs, does not reach for a climactic run to prove he can hit it. The discipline is more convincing than any melismatic display would have been. “Love Inside” works in a similar register, with BJ treating desire as if it were a private conversation overheard rather than a performance staged for witnesses. These are the moments where In My Mind stops auditioning and starts breathing, where Sledge’s church training shows up not as showmanship but as an understanding of how to sit inside a sustained note and let it do the talking.

Aaron and Scooter Sledge, BJ’s siblings, were embedded in the sessions, and their involvement tightened the record’s moral vocabulary in ways that extend beyond credits. A cut like “Woman’s World” does not happen in a vacuum. It comes from a household where women were addressed with specificity, where the language of respect was not abstract but domestic and daily. That proximity kept BJ’s love-writing grounded when it could have floated into the empty chivalry that male R&B performers sometimes adopt like a costume. When he pledges himself to a woman, the specificity sounds inherited, shaped by watching how the men around him spoke to the women in the room, which words they chose and which ones they swallowed.

Saadiq’s fingerprints surface on “The New Cupid” as a retro-soul guitar figure and a rhythmic pocket that belongs to an earlier decade’s idea of courtship music. BJ is not imitating Saadiq. He is borrowing a musical argument about what romance should sound like when it takes itself seriously, when the performer refuses to wink at the audience or hedge his declarations with irony. Saadiq built his solo career on the conviction that modern R&B had surrendered too much to detachment, and BJ picks up that thread without pretending to own it. The distinction matters. BJ is not a revivalist. He is a contemporary artist who happens to believe that direct address is more interesting than the slurred, inebriated style that dominated commercial radio in the mid-2010s. His vowels say as much. Every one is deliberate. Every consonant closes where it should.

In My Mind asked for a bargain that the mid-2010s R&B market was not offering. It demanded that a man be allowed to sound like an adult without sounding old, to write about women without either worshipping or objectifying them, to pray on one track and flirt on the next without anyone demanding an explanation for the inconsistency. BJ did not resolve these contradictions on the record. He displayed them, let them scrape against each other, and trusted that the discomfort was the point. The album did not sell in numbers that justified Motown’s four-year wait. It did earn BJ a Grammy nomination for Best R&B Album, which confirmed what anyone paying attention already knew: the craft was never the problem, and neither was the writing.

The unfinished question In My Mind left behind is whether that kind of R&B adulthood can survive without constant co-signatures. BJ sang about self-sufficiency on a record crowded with collaborators. He preached the restoration of tenderness while sharing the microphone with artists whose fame dwarfed his own. He claimed the title of the new Cupid and then handed the bow to guest after guest, each one dependable, each one a reminder that the label did not trust the arrow to fly solo. Nine years later, the recordings hold because Sledge’s instrument carries a gravity that outlasts the commercial calculations surrounding it. But the question the album posed has never been cleanly answered, and maybe that is why it still pulls at anyone who returns to it. BJ built a thing that was patient and grown and principled and populated it with proof that patience was not enough to get the door open all the way.

Damn, BJ really has been suffering from a marketing issue his entire career. I lived in Chicago during the Pineapple Now-Laters era and saw him perform, brother was drinking a bottle of Remy on stage and hitting falsettos flawlessly. You had it right when you said the craft and the writing were not the problem, it’s really the positioning. I always wonder if he came out during an earlier era would it have been different for him.