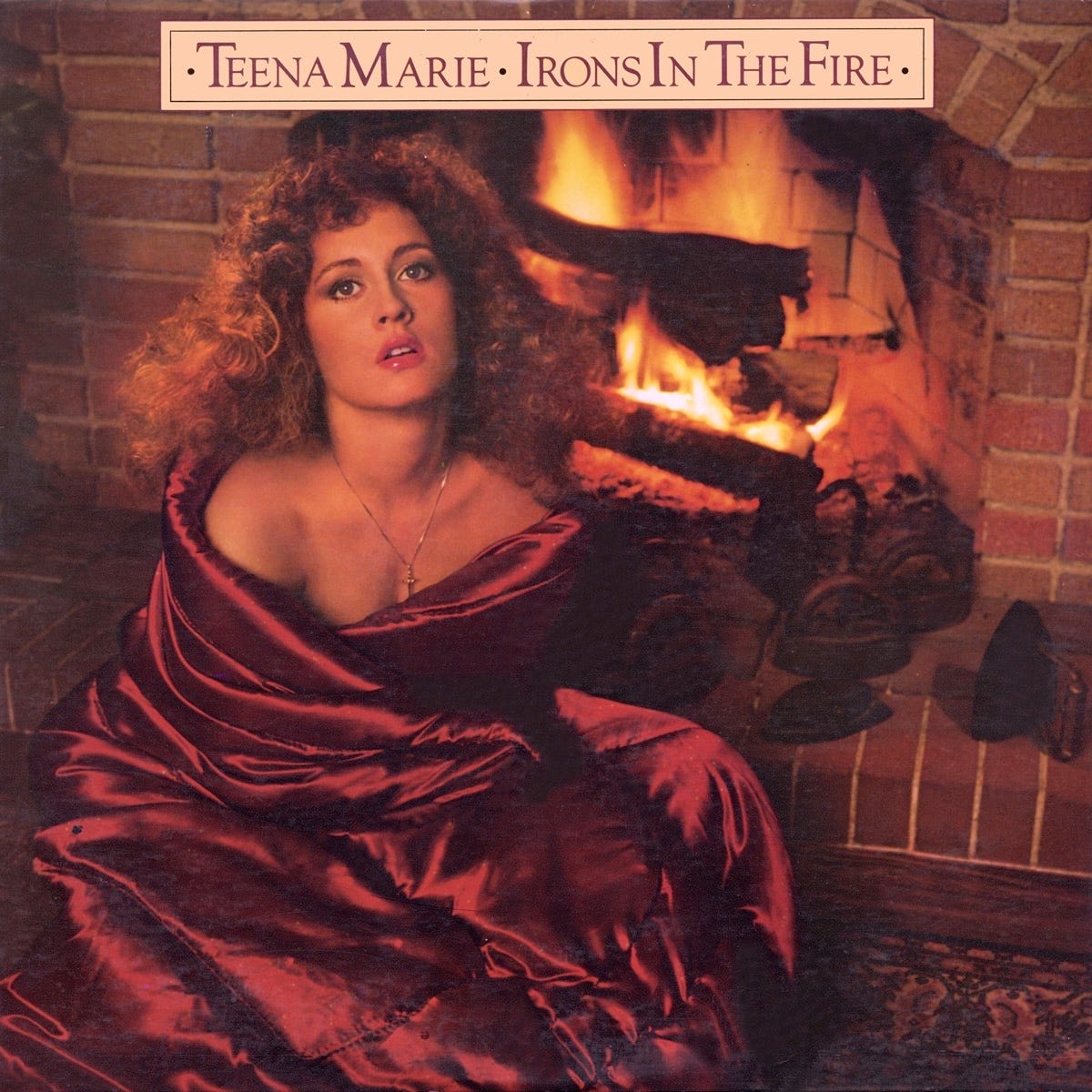

Anniversaries: Irons in the Fire by Teena Marie

Irons in the Fire is not only a career pinnacle but also a manifesto: the moment Teena Marie became the boss of her sound and, in doing so, cleared a path for others to follow.

The house lights fade, then flare again as Teena Marie wheels on her rhythm section mid-groove and barks “Stop!” before the room can take a breath. She leans into the microphone, calm and absolutely certain, and tells the bassist that she wants her line, the part she wrote, the line that makes “I Need Your Lovin’” live and breathe. In that split second, the audience witnesses a performer who is no longer content to interpret someone else’s charts. She is the arranger, the writer, the producer, and the leader with the authority to halt the show until every note aligns with her intention. That insistence anchors the 45-year legacy of Irons in the Fire, an album that captured Mary Christine Brockert claiming full command of her sound and, by extension, challenging an industry that rarely allowed women, especially women working inside Motown’s hit factory, to steer the entire ship.

Her music career began in 1976 when Hal Davis, the veteran Motown producer who once guided the Jackson 5, arranged an audition for Brockert after hearing her studio demos. Motown signed her, yet shelved several early recordings, relegating the young singer to days of background sessions and nights of unrealized promise. Salvation arrived when Rick James caught one of those sessions, heard grit and gospel in her phrasing, and offered to helm what became her debut, Wild and Peaceful, in 1979. James’s songwriting framed her voice in slap-bass funk and earned her first R&B hit, “I’m a Sucker for Your Love,” yet Brockert still felt like a guest in her own story.

Motown executive Hal David hoped to soften that image. He paired her with Richard Rudolph for the follow-up, Lady T, released on Valentine’s Day 1980. The record shimmered with West Coast strings and ballads dedicated to Minnie Riperton, showing that Brockert could co-write sophisticated pop while sharpening her arranging chops. Commercial momentum from “Behind the Groove” granted leverage, and she negotiated the right to self-produce the very next project. Five months later, sessions for Irons in the Fire began, with Motown house unit Ozone and members of the Stone City Band taking cues from her final word on every chord change.

“I Need Your Lovin’” opens the album with a rubber-band bass figure she laid out on guitar, later transposed by Allen McGrier for maximum bounce. Her doubled lead vocals—one track punched for clarity, the other pushed for power—ride that groove like a brass section, building tension before Ray Woodard’s tenor sax cuts loose. Berry Gordy at first doubted its hook count until Marie argued that the bass, the chant of “M-O-N-E-Y,” and the chorus made three hooks, not one. Radio programmers agreed, spinning the single night after night until it dominated playlists and introduced her name to crossover audiences without a single cameo from James.

With “Young Love,” the tempo cools, yet the rhythmic syncopation in the Rhodes piano stabs remains, popping against her conversational phrasing. She confesses in half-spoken asides, then vaults into melismatic runs that glance off gospel cadences learned in Venice Beach storefront churches. “First Class Love” follows with layered background stacks that riff on doo-wop traditions, while the clavinet and congas share equal billing, proving that her arranging ear favored interplay over simple spotlighting. The title song tempers the set with a slow burn that centers vibrato and restraint, an ode to her late father articulated through vocal dynamics rather than strings or swelling horns.

Side two begins with “Chains,” a seven-minute blues where she multitracks harmony parts into a call-and-response choir, then resolves the arrangement with a sudden falsetto bridge that cuts the groove free of any easy cadence. “You Make Love Like Springtime” injects samba accents, Paulinho da Costa’s shakers and surdo framing verses that slide between major and minor coloration. She scats through the fade as if testing the limits of her own phrasing. “Tune In Tomorrow” completes the suite in modal jazz territory, stretching over six minutes so that Daniel LeMelle can take a tenor solo while Marie answers phrases on electric piano before trading four-bar statements with the horn section. Instead of a formal ending, she calls the band down to a hush and resolves on quiet Rhodes voicings, confident enough to let silence speak.

By writing, producing, arranging, and performing every part on a major-label, Marie broke a barrier Motown had maintained since its inception. Her precedent offered proof that women could sit at the control board and guide session musicians without outside supervision, a reality that later informed the careers of Narada Michael Walden protégé Angela Winbush, Janet Jackson collaborator Lynn Mabry, and Missy Elliott, each citing Marie’s autonomy as a blueprint. The album also demonstrated that an artist could honor label roots while expanding into jazz, Latin, and deep-soul territories, encouraging Motown to grant wider creative space to acts like DeBarge and Tata Vega in the early Eighties. Legal disputes she later waged with the label set case law that protected recording artists from contracts without release guarantees, a battle waged with lessons learned during Irons when she first experienced complete control.

The musicians, decades later, still study the record for its integration of live-band energy and studio finesse. Bassists transcribe McGrier’s line for technique clinics. DJs drop the extended cut of “Tune In Tomorrow” during quiet-storm sets for its open-ended solos. Songwriters point to the intervallic leaps in “Young Love” as a lesson in writing melodies that challenge and reward a vocalist in equal measure. The record endures because every choice flowed from one vision—Teena Marie’s, expressed without compromise. In that respect, Irons in the Fire stands not only as a career pinnacle but also as a manifesto: the moment a brilliant singer became the boss of her sound and, in doing so, cleared a path for others to follow.