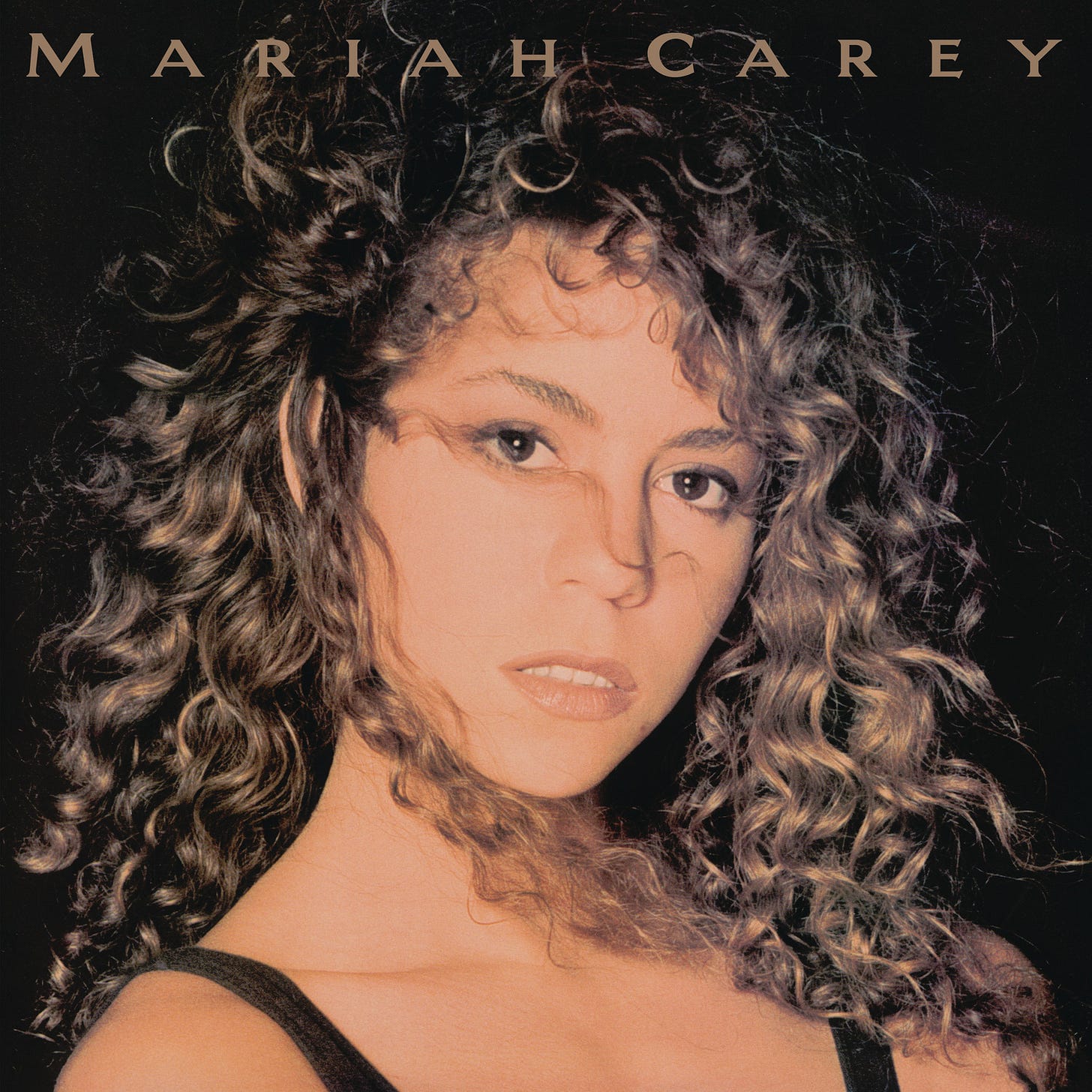

Anniversaries: Mariah Carey by Mariah Carey

Many contemporaries had delivered impressive debuts, yet few wrestled so directly with questions of belonging. The music succeeds because it merges a young woman’s history with accessible craft.

Mariah Carey still hums with the voltage of new ideas thirty-five years since the debut album was released (and the latest track, “Type Dangerous,” came out last week). Rather than a sealed museum piece, the record moves through playlists and social media edits as something akin to shared scripture, quoted whenever a singer bends a note into a curlicue or floats above a chorus in a piercing whistle pitch. Because Carey helped write every selection and shaped the blends of her own background vocals, the album reads as an autobiography rendered in sound, as a young Black woman of mixed heritage insisting that her full range, both literal and cultural, deserved center stage. The commitment to that premise gives the project its abiding charge. Even listeners discovering it today sense that the voice is not merely showing off; it is sketching an identity that the singer would spend the next three decades defending and refining.

Many contemporaries had delivered impressive debuts, yet few wrestled so directly with questions of belonging. Carey entered an industry that still sliced its talent into narrow bins—“pop” here, “R&B” there, racial categories everywhere. She refused the sorting hat. The album’s sequencing toggles between gospel-tinted balladry, freestyle-leaning dance grooves, and a brief flirtation with rap cadences, signaling an outlook bigger than any single shelf. That stance mattered for audiences who rarely saw a multiracial woman present herself without explanatory footnotes. Later conversations about authenticity often cite this record as an early marker of change, proof that a singer could own layered heritage and still command mainstream formats without dilution.

With the production team of Rhett Lawrence, Narada Michael Walden, Ric Wake, Walter Afanasieff, and Carey herself, they adopted a guiding principle: build arrangements that magnify the lead vocals, never crowd them. Keyboards pulse in clean lines, drum machines arrive in measured pops, guitars accent rather than dominate. Reverb stays short so that each breath retains tactile presence. Compared with the maximalist studio habits of the late-eighties period, the mixes feel newly spacious, almost airy, leaving room for expression rather than studio pyrotechnics. That restraint would become foundational wisdom for modern pop and R&B sessions, where producers now carve mid-range gaps to let singers improvise above the grid. Carey’s debut modeled that approach before it became conventional.

Do we have to explain “Vision of Love” as the opener? But for starters, a slow 6/8 pulse supports gospel-style chord changes, yet most of the arrangement consists of Carey cloning her own harmonies and letting them fan out like stained-glass light behind the main melody. Midway through, she delivers a now-textbook descending run that stretches one syllable across half an octave; generations of aspiring divas would later practice that flourish in bedroom mirrors. One writer went so far as to nickname the song the “Magna Carta of melisma,” and the description sticks because the track codified a vocabulary that reality-show hopefuls still deploy. Crucially, the technique never feels ornamental for its own sake. Every vault or slide underlines the relief at emerging from hardship, and the sonic minimalism ensures that no cymbal crash intrudes on the story. Pop had heard acrobatic voices before, yet rarely had the trapeze work been framed with such spacious clarity.

Where the big single broadens the stage, “Vanishing” pulls the curtains until only a piano and a room mic remain. Carey produced this ballad herself and later explained that overdubs would have blunted its directness; a brief experiment with a drum track was scrapped for sounding intrusive. The decision proves inspired. Pedal creaks, fingertip-soft key strikes, and the subtle intake of breath place the listener in the studio at arm’s length from the singer. Modulations arrive not through flashy key changes but through the gentle drift between chest and head registers. Club-ready swing enters “Someday,” built on punchy drum programming and chopped guitar embedded where horns once sat in the demo. Carey originally preferred the brassier arrangement, but corporate hands replaced it during final edits. What could have become a compromise turned into a showcase of adaptability.

For this torch song, which is “I Don’t Wanna Cry,” nylon-string guitar sketches a circular motif while light percussion ticks in the background. Walden’s arrangement respects negative space: each verse almost whispers, then lungs open on the refrain, tracing the inner debate over holding on or letting go. Carey’s dynamics do the heavy lifting, switching from conversational confession to open-throat exclamation within a single breath. “Prisoner” is the album’s outlier, hinting at future genre cross-pollination. A freestyle-flavored groove shuffles beneath half-spoken lines that borrow cadence from rap, followed by rapid-fire sung hooks. The experiment feels playful, perhaps even raw, but it sends a clear signal that Carey is comfortable shifting between pop melodies and rhythmic patterns.

Legend has it that this ballad almost missed inclusion. Executives heard a rough cassette on a flight and declared that the album felt incomplete without it. Afanasieff built “Love Takes Time” in a whirlwind, layering gentle synth pads, muted drum hits, and a quiet organ line while keeping the central channel clear for the vocal. The story highlights Carey’s dual reputation as a studio workhorse capable of all-night sessions and as a songwriter whose late additions can shift the emotional center of a project. On record, every production choice serves the lyric’s patience. Harmonies arrive like sighs rather than stacked choirs, and the final high note hangs just long enough to feel earned, never indulgent. The song’s inclusion, invisible on some first-run cassette inserts, became a symbolic victory—proof that the artist’s instincts could override schedule pressures when the music demanded it.

The album’s influence extends beyond melodic technique. By crediting herself on songwriting and background vocal arrangements, Carey challenged a long-standing template in which Black women singers provided voice while male producers claimed authorship. Her insistence on creative fingerprints affirmed that a woman of color could be a principal architect, not a featured ornament. In later years, many emerging acts cited the debut as evidence that they, too, could negotiate ownership clauses and demand points on publishing. Melisma, once associated mainly with gospel, became a mainstream thrill; whistle tones shifted from novelty to standard aspirational feat for reality-show hopefuls; sparse piano ballads regained commercial viability. Within fan communities and academic panels, the set is often referenced as a text that re-centered the idea of virtuosity around emotional argument rather than gymnastic display.

Carey quietly produced “Vanishing” herself, signaling both confidence and impatience with being a guest in her own sessions. She argued over the horn removal in “Someday,” foreshadowing later battles where she would scrap entire mixes if they did not serve the vocal narrative. Outside the studio, media questions about her racial background pushed her to articulate an identity that marketing departments found inconvenient. The tension between industry packaging and self-definition only intensified over subsequent releases, culminating in later projects where she fused hip-hop samples with pop choruses and even recorded an undercover alt-rock album to bypass corporate oversight. The debut, in retrospect, documents the starting line of that arc. Its songs exhibit a performer already negotiating with gatekeepers, already listening to her own instincts over external advice, and already willing to leverage tireless work habits to protect the art. That determination would inform her eventual renaissance as an architect of genre-blending hits and as a symbol of artist-run strategy in a field that often sidelines such voices.

Spin the record now, and its fingerprints appear everywhere, from micro-runs in bedroom-recorded R&B on streaming platforms to the piano-voice ballads that dominate televised talent shows. Artists who were not yet born when Carey tracked “Vanishing” quote its phrasing instinctively; producers who once filled every bar with layered drums now leave air in the mid-range because this album demonstrated how silence can make a note glow. The music succeeds, finally, because it merges a young woman’s personal history with accessible craft. Every whistle tone carries the weight of someone pushing against confinement, every subdued verse hints at a singer who knows when to hold power in reserve. Three decades later, the lessons remain relevant. Claim authorship, respect space, trust your emotions, and find the courage to express yourself authentically. Those lessons continue to guide pop and R&B alike, ensuring that the debut never settles into nostalgia but stays in circulation as lived, shared scripture.

Sweet sweet prose!