Anniversaries: On Top of the World by 8Ball & MJG

Eightball & MJG built an album that both celebrated and challenged the G‑funk template. It is a blueprint that informs how Southern rappers approach production, storytelling, and collaboration.

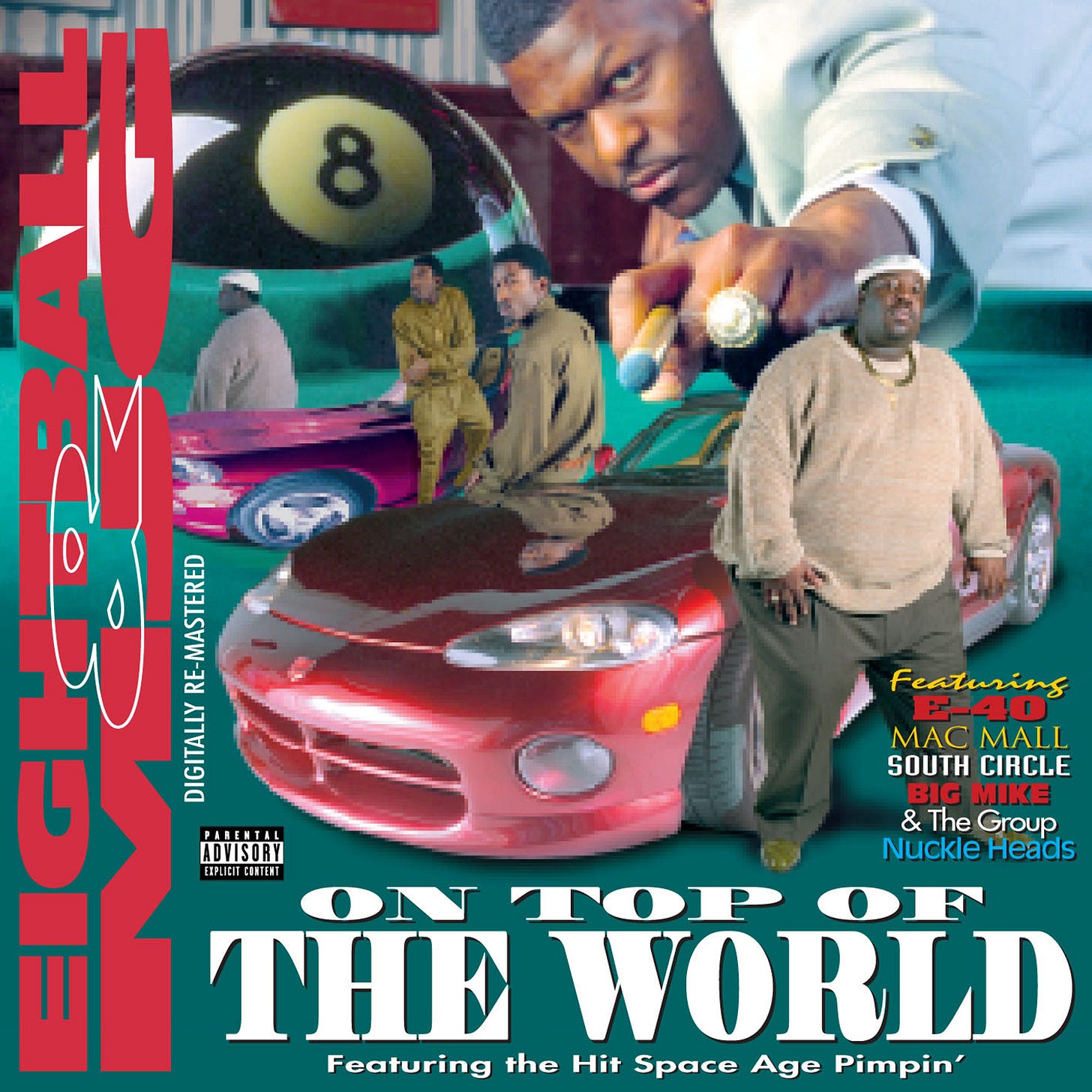

On Halloween night 1995, when West Coast G-funk dominated car stereos from Compton to Cleveland, a record from Memphis slipped into the national conversation. On Top of the World was Eightball and MJG’s third album, recorded at Digital Services in Houston and released by Suave House and Relativity Records. Its title was aspirational and prophetic: within a week, the duo’s portraits, rendered in flashy Pen & Pixel graphics, were stacked in record stores across the South. Within months, the project was certified gold, and by year’s end, it sat at number 8 on Billboard’s album chart while climbing to number 2 on the magazine’s R&B/Hip-Hop list. For a pair of rappers from the Orange Mound neighborhood in Memphis who had spent the previous five years selling cassettes out of car trunks, the numbers were validation; On Top of the World confirmed that their region’s stories could resonate beyond state lines.

The album arrived amid the afterglow of Dr. Dre’s The Chronic. Synth-heavy party music from Los Angeles had reshaped hip-hop in the early ’90s, and every city seemed to be adopting G-funk’s warm synths and rubbery bass. Eightball & MJG were fans of that sound, but they viewed it through a distinctly Southern lens. According to AllMusic’s retrospective review, the duo built on Dre’s G-funk stylings, making the music “rougher and rawer.” Producer Tony “TMix” Draper had been working with them since their debut Comin’ Out Hard. For the new album, he layered his synths with live instrumentation and samples that felt humid, not polished, building a sound that helped put Orange Mound and Memphis on the hip-hop map. Heavy basslines, cold snares, and thick synths formed backdrops for the duo’s street stories. The beats flirted with West Coast slickness but were anchored by Memphis grit; the overall vibe was more juke joint than party yacht.

The voices riding those beats were just as distinct. Eightball (Premro Smith) had a rich, unhurried baritone that seemed to roll across a track like smoke; his verses unfurled slowly, filled with patience and grounded detail. MJG (Marlon Goodwin) rhymed in a higher, more percussive register, pressing syllables into a beat and cutting through it with clipped precision. Together, they had been refining their chemistry since their days performing at Ridgeway High School talent shows. Their earlier albums were filled with rough edges—keyboard loops, live guitar licks, and samples of soul records—and critics praised their unflinching depiction of life in Orange Mound. On the new project, they retained the grit, but TMix’s production was more expansive, filling each song with layered synths and talkbox embellishments reminiscent of Roger Troutman’s work; RapReviews observed that the album’s “Roger Troutman–esque funk” on the title track “begs to be played over and over again.”

“Pimp in My Own Rhyme” leads the album after the brief instrumental intro. Over a mid-tempo groove anchored by whiny synths and stuttering drums, Eightball reintroduces himself with an easy drawl. His early vocals are noticeably higher than the gravelly tone fans associate with him. That youthfulness is part of the track’s charm: “Unh, light up the bomb, cause here I come/It’s Eight-bizall got the remedy,” he raps, stretching vowels with Southern patience. MJG follows with a verse that is both brash and instructive, boasting of sexual prowess and hustler ethics. The duo’s subject matter—weed, women, hustling—remained consistent across albums, but their delivery made even the most salacious lines sound like parables about survival.

“What Can I Do” tries to push the formula further. TMix lays down a horror-movie synth line and menacing bass, but it was found “cheesy” and unfavorably compared to Bushwick Bill’s Chucky songs. The track’s melodrama hints at the duo’s willingness to experiment but also shows the limits of their horrorcore influences. Much stronger is “For Real,” which pulses with warm synthesizers and handclaps, and “Funk Mission,” where the duo shifts gears to discuss addiction’s toll. The beat is slower, the bassline thick, and 8Ball’s voice almost trembles as he narrates the downward spiral of a friend. MJG’s verse is equally sobering, and there is a rare moment where they allow a hook to breathe—Nina Creque’s background vocals float in the mix like smoke.

On “Kick That Shit,” TMix returns to muscular funk, letting DJ Squeeky’s scratches cut through the chorus while the rappers trade boasts. The track exemplifies the duo’s ability to stretch limited subject matter into compelling storytelling; they know they’re repeating themes, but they approach them with such confidence that it feels fresh. This confidence peaks on “Break ’Em Off,” which became one of the album’s defining singles. The track charges forward over rising keyboard stabs and a hypnotic bassline. MJG sets things off with a barrage of threats and colorful metaphors, ending his verse with a warning that if a cheating husband comes home early, he’ll “have to break him off.” When 8Ball arrives, he nods to hip-hop’s coasts: “All respects to the west, big ups to the east/Southside represent, blowing up like Jesus.” A few bars later, he makes the mission clear: “Tennessee – Memphis, Tennessee precisely/Southern brothers gotta break yo’ ass off politely.” These lines show gratitude for hip-hop’s pioneers while asserting a new Southern center. The hook—“Break it up, break it up, break ’em off proper”—is a chant built for block parties and trunk-rattling rides, and the interplay between the rappers captures their chemistry at its loosest.

Midway through the album, TMix flips the script with “Friend or Foe.” A reflective posse cut where bravado gives way to introspection, the track features Bay Area legends E-40 and Mac Mall, along with former Geto Boys member Big Mike. The beat is moody, leaning into West Coast chords and a low-slung groove. E-40 opens with a story about childhood friendship: “Some had it all doe, but less unfortunate/You had an alloy spoke Mongoose and I had a Huffy.” He recalls building a go-kart from used nails and going to church together before discovering his friend had taken to armed robbery—a narrative that underscores how quickly trust can erode. Mac Mall and Big Mike continue the theme, layering suspicion with spiritual overtones. When the hosts return, 8Ball’s verse is cautionary (“You ain’t my best friend, you’re another foe/And bitch you ain’t my main thing, you that other ho”) while MJG’s flow borders on stream-of-consciousness, wrestling with loyalty and betrayal. The combination of voices makes the song feel like a council meeting: each rapper presents evidence, and the listener must decide who is friend or foe.

“Hand of the Devil” follows, built on slyly strummed funk that RapReviews described as being in “wry contrast to a song about being led into doing bad.” The track is almost cinematic, with swirling strings and whispery background vocals, while the lyrics describe being tempted into violence and crime by unseen forces. The song stands out because it mixes cautionary storytelling with the group’s usual braggadocio; as 8Ball laments the pull of greed, MJG’s verse pushes back, reminding listeners of personal agency. The chorus—“It’s the hand of the devil, devil, devil”—loops like an incantation.

The album’s centerpiece arrives with the title track. TMix flips Isaac Hayes’s “The Look of Love,” turning a soul ballad into something humid and regal. Instead of samples buried beneath layers of drums, the horns and strings are front and center, bathing the song in Memphis soul while synths swirl around them. The arrangement is a celebration and a warning. There is no hook chasing; a hypnotic chorus loops like a mantra, reinforcing the weight of the title. 8Ball opens with a calm, grounded flow, stacking memories and hustles into something smooth and dignified. His tone is reflective rather than boastful; he speaks from the perspective of someone who has climbed without forgetting the ladder beneath him. MJG’s verses cut through jealousy, betrayal, and industry chaos with razor-sharp precision, riding the instrumental like slow smoke. The track sits in its own atmosphere; it’s the sound of two men surveying the landscape of mid-’90s hip-hop and claiming a peak without shouting about it.

The introspection continues on “What Do You See,” featuring Nuckle Heads, and “In the Line of Duty,” where South Circle contributes. These songs question the price of success and the responsibilities that come with influence. “All in My Mind,” featuring South Circle again, is almost meditative; the beat slows down to a crawl, and the rappers reflect on mental health and anxiety—topics rarely explored openly in mid-’90s rap. “Comin’ Up” brings the energy back with crisp snares and a sample of black-church gospel; RapReviews singled it out as a classic that “will never get old.” It’s a song about upward mobility delivered without condescension—the duo celebrate their hustle while acknowledging the friends still stuck in the trenches.

Then there’s “Space Age Pimpin’.” This cut is a vision of what comes next. TMix crafts a futuristic groove with whirring synths and a slow, seductive beat that feels both cosmic and terrestrial. The song’s hook is sung by Nina Creque, whose voice drifts like a spaceship over the beat. In his first verse, MJG outlines what “space age pimpin’” looks like: “Who knows, fine clothes/Lexus doors you’ll be closin’.” He describes different faces in different places tied to him like shoelaces, promising a lifestyle of travel and seduction. Eightball counters with a verse that feels grounded; he talks about keeping it real and communicating truthfully. The interplay encapsulates the duo’s dynamic: one imagines a futurist fantasy of pimp culture, while the other keeps the day-to-day realities in view. It’s no wonder that the song is often cited as one of their signature cuts, carrying a groove so thick you can “hear the strip club in the background.” The track isn’t designed for radio; it’s meant for real time, real streets, real people.

The album closes with “Break ’Em Off,” returning to the energy of the first half. After spending the latter tracks in introspection, the duo ends with a reminder of their roots. The bassline is menacing, the synths swirl, and DJ Squeeky scratches like a siren. 8Ball’s fourth verse on the song reinforces the album’s mission: “It’s that nigga from the southside—8Ball/Much game, true hustler, mack as long as the gray wall/Tennessee – Memphis, Tennessee precisely/Southern brothers gotta break yo’ a off politely.” The call to break off the competition politely is both a threat and an invitation—recognize the South’s arrival, and everyone can eat.

Beyond the music, On Top of the World was a blueprint for what would become known as Dirty South rap. TMix’s beats drew heavily from the West Coast G-funk wave but gave it a distinct twist; songs like “Pimp in My Own Rhyme” and “Break ’Em Off” thrive on funky synths, thumping basslines and rhythms that pulse with swagger unique to the South. The sound dipped between smooth grooves and harder, menacing tones. The duo showed versatility; they dove into the highs and lows of street life with vivid detail and reflective tone. They tackled drug addiction on “Funk Mission,” greed and consequences on “Hand of the Devil,” and loyalty and betrayal on “Friend or Foe” with the help of Mac Mall, E-40, and Big Mike. They shifted effortlessly into smoother territory on “Space Age Pimpin’,” crafting a seductive anthem with a futuristic funked-out vibe. Even the introspective tracks about industry struggles, like “What Can I Do” and “What Do You See,” showed that success didn’t erase the weight of their origins. At nearly seventy minutes, the album could have felt bloated, but every track served a purpose, building a cohesive narrative that highlighted the duo as true giants of Southern Hip-Hop.

The West and East coasts were locked in a high-profile rivalry. Southern rappers had to fight for recognition, and many outside the region dismissed their slower tempos and drawled cadences. Eightball & MJG’s previous work had gained a cult following, but On Top of the World gave them mainstream momentum. The album’s success signaled that the South could take G-funk aesthetics and make something entirely its own. In doing so, it paved the way for later classics like UGK’s Ridin’ Dirty and OutKast’s ATLiens. The latter’s cosmic production and philosophical lyrics may have seemed left-field to those only familiar with East Coast boom-bap; yet both records share DNA with 8Ball & MJG’s willingness to blend funk, soul, and street narratives. ATLiens would go on to become a cornerstone of Southern rap, but the ground had been tilled by On Top of the World.

The album’s influence can be felt in the Dirty South’s continued emphasis on bass, atmosphere, and honesty. It introduced the trunk-rattling, thick-synth template that became the default for Memphis and later Houston production. It showed that introspection and hustler swagger could coexist on the same record. It also underscored the value of regional authenticity. When 8Ball saluted both coasts on “Break ’Em Off,” he did so not as a subordinate but as an equal, making room for the South’s own stories. The duo’s contrast—Ball’s baritone patience and MJG’s percussive urgency—became a model for later Southern pairings. Their interplay is cited in lists of influential songs because it taught younger rappers how to trade verses without losing individual identity.

By weaving West Coast synths into Memphis grit, alternating between pimp fantasies and cautionary tales, and bringing in guest artists like E-40, Mac Mall, and Big Mike to broaden their sonic palette, Eightball & MJG built an album that both celebrated and challenged the G-funk template. On Top of the World is not simply a relic of 1995; it is a blueprint that continues to inform how Southern rappers approach production, storytelling, and collaboration. The record’s rough edges remain, but that rawness is part of its power, reminding us that hip-hop’s most significant shifts often come from artists willing to take an existing style and flip it for their own environment—adding more bass, more honesty, more warmth. For Eightball & MJG, reaching the top of the world meant bringing the South with them, and their view from the summit changed the rap landscape forever.