Anniversaries: Overly Dedicated by Kendrick Lamar

Overly Dedicated may have begun as “just” a mixtape, but today it stands as a crucial piece of the Kendrick Lamar story—the moment the good kid from Compton first showed he was great.

A bitter winter wind whistled through Atlanta as a young hip-hop devotee sat hunched against the cold, headphones on, letting J. Cole’s Friday Night Lights mixtape warm the night. It was late 2010, and Cole had just surprised everyone by naming an unknown Compton kid’s project, Overly Dedicated, as his favorite album of the year. Intrigued by that co-sign, the listener pressed play on Kendrick Lamar’s mixtape expecting greatness. At first, disappointment set in—the rapper’s voice sounded youthful, scratchy, almost too raw—and after a few tracks the listener switched back to Cole’s tape, wondering what Cole heard in this newcomer. But something about Kendrick’s music lingered, calling for a second chance. On that second listen, the opening track “The Heart Pt. 2” hit like an audio punch to the gut. What started calm and conversational suddenly built into a volcanic rush of emotion—Kendrick’s raspy voice, initially off-putting, now cloaked itself in relentless passion as he poured out bars with breathless intensity. By the time the song peaked in a flurry of gasping syllables, the listener was floored. The talent Cole had recognized became obvious. The good kid from Compton had made his first convert, and there would be many more.

Looking back now, Overly Dedicated (OD) reads as a pivotal chapter in Kendrick Lamar’s evolution—essentially the demo tape that birthed his career. It was self-released in September 2010 (even sold on iTunes, not just given away) and marked Kendrick’s first project under his real name rather than the earlier “K.Dot” alias. In these tracks, you can hear the raw DNA of a future rap icon. Gone was the youth who once chased Lil Wayne’s style; on OD, Kendrick found his own voice and the confidence to make others believe in his vision. The youthful, scratchy tone that initially threw some listeners off foreshadowed the candor and vocal intensity that would define his later work. In hindsight, OD plays like a rough sketch for the artist he would become, with themes and storytelling techniques that would recur throughout his career. This is Kendrick before the “alien” vocal effects and the avant-jazz experiments—a pure hip-hop storyteller built on incisive lyrics and substance. For anyone seeking to understand where the good kid, m.A.A.d city saga truly began, OD remains essential listening.

One of the tape’s clearest through-lines is Kendrick’s examination of vice and escapism, a strand he would revisit in hits years later. “P&P 1.5” (short for “Pussy & Patron”) sits as an early draft of 2012’s “Swimming Pools (Drank),” spotlighting two vices—sex and alcohol—as ways to cope with pain. Over a woozy beat, Kendrick recounts a scene of violence and trauma before asking why people drown their sorrows in liquor and lust. The resonance is plain: people going through storms reach for what feels like shelter. “P&P 1.5” even opens with a snippet from the sitcom Martin—a playful nod to one of Kendrick’s favorite shows—easing the listener in before the song plunges into darker ground. Kendrick was only in his early 20s, yet he showed a sharp awareness of how young people self-medicate trauma. The unflinching look at alcohol’s grip, perfected later on “Swimming Pools,” has its roots here.

Right alongside indulgence is the seed of abstinence and conscience. On “H.O.C.” (“High Off Contact”), Kendrick says plainly that he doesn’t smoke weed—a rare stance in a rap scene that often glorifies getting high. “All the real smokers get me high off contact,” he raps, meaning he catches a contact high just being in the room but refuses to take a puff himself. Surrounded by studio smoke, young K.Dot felt like “a nerd” for being the only one not lighting up, yet he held his line. That early aversion wasn’t just a quirk; it hints at the moral framework and faith that would later anchor his music. With good kid, m.A.A.d city, fans would learn why: in that album’s narrative, a friend’s death and the chaos of intoxication affirm Kendrick’s decision to stay sober as self-preservation. On OD, “H.O.C.” serves as a quiet precursor to that revelation—the good kid asserting his difference amid a culture of blunt smoke. Conscience breaks through the haze, a hint of the spiritual battles to come.

OD also introduces Kendrick’s world—Compton—in unvarnished detail. Across the tape, he sketches inner-city life he knows: uncles in jail, boys growing up fatherless, families scraping by as “jobs aren’t kept,” and innocent people never truly safe. He shows how the lure of money can push even good people toward despair or crime. Crucially, Kendrick places himself in the picture not as a lofty observer but as one of many navigating the madness. On “Average Joe,” he embodies a normal kid who nearly gets pulled into gang violence, recounting a shooting he narrowly escaped—“thought about that so long I had failed my finals,” he admits, the trauma derailing his schoolwork. The anecdote reinforces how close he came to a darker path. Tracks such as “Ignorance Is Bliss” drive the point home. Over ominous production, Kendrick adopts the voice of a young gangbanger who boasts about murder and mayhem with a cold shrug—but he ends each verse by repeating “ignorance is bliss,” flipping the bravado to expose a cycle of blind violence. The refrain frames the character’s actions as the product of not knowing better—“we know not what we do,” the song implies. This kind of layered storytelling—glamorizing on the surface while subtly condemning—recalls the best of Tupac and Nas, and Kendrick carries that torch. OD’s Compton isn’t the glamorized “hub city” of carefree gangster myth; it’s a maze of moral traps and hard consequences, the training ground for the narratives that would solidify good kid, m.A.A.d city.

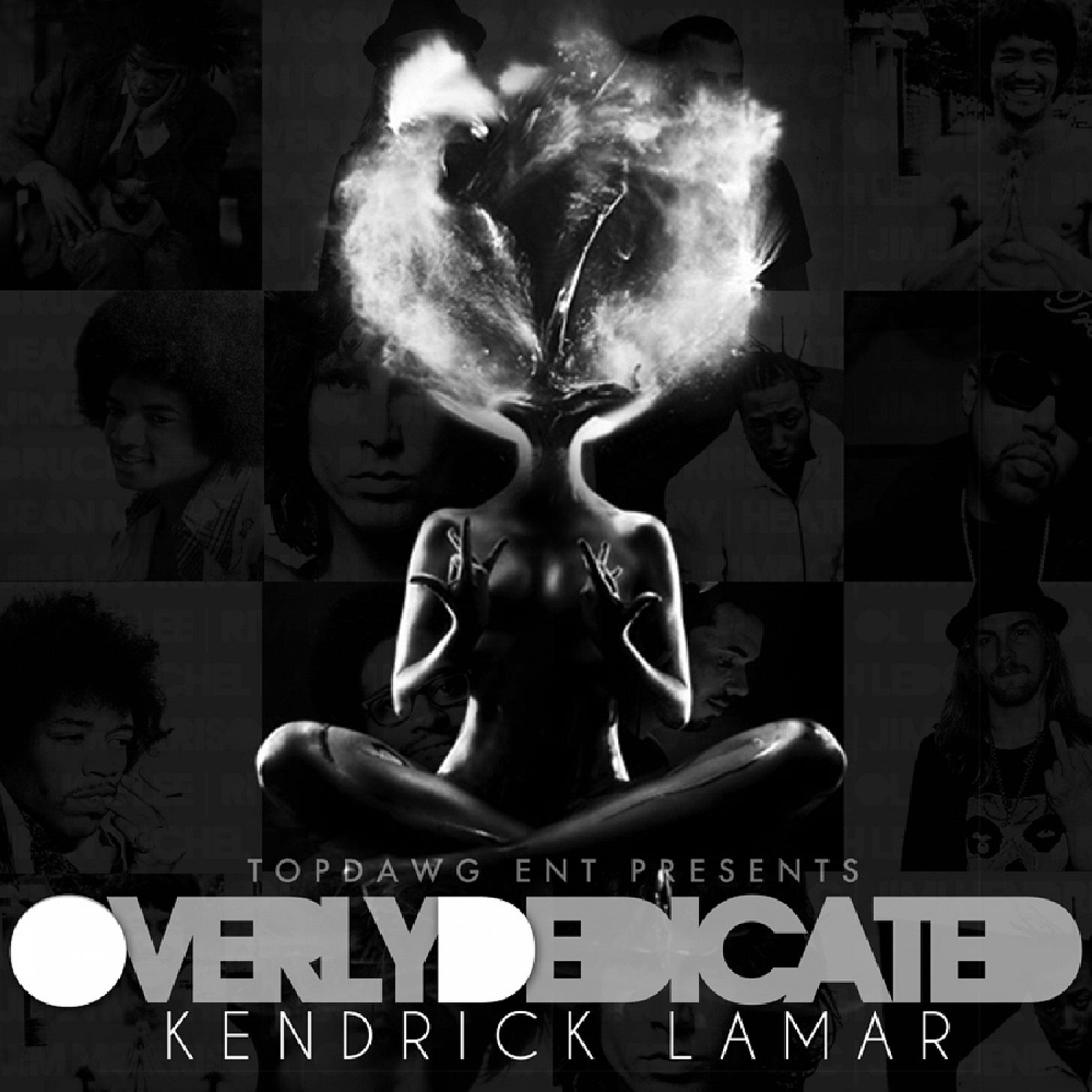

Beyond the street-level detail, OD is haunted by a spiritual preoccupation with mortality and legacy. Even the cover art speaks to it: a meditating figure with its head crumbling into ether, set against a collage of famous faces—Michael Jackson, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain, Bruce Lee, Pimp C—artists deeply committed to their craft who died young. That background isn’t just a tribute; it’s a statement. By placing himself in front of the “27 Club” and other fallen icons, Kendrick asks what it means to burn bright and burn out. Is over-dedication a path to greatness, self-destruction, or both? The title itself carries a double meaning: OD as in overly dedicated—extreme commitment—and OD as in overdose, the fate that befell several of those icons.

The theme is reinforced from the start: “The Heart Pt. 2” opens with a snippet of the New York artist Dash Snow reflecting on life. It’s an eerie choice—Snow died at 27—which casts a ghostly shadow on the music. Kendrick’s verse that follows is like a man possessed, rapping as if racing against death and pouring everything into the mic. And on the final track, “Heaven & Hell,” he contemplates salvation, sketching an afterlife vision. The vocal cuts off mid-thought, as if he hasn’t found the answers yet. Before he would have full conversations with God and the Devil on To Pimp a Butterfly—debating “Lucy” (Lucifer) in songs—here we see a young Lamar already wrestling with sin and redemption. The fear of dying before making a mark, and the hope for something beyond this life, run forward into “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst” on good kid, m.A.A.d city, across To Pimp a Butterfly, and through the soul-baring tracks of DAMN. In OD, we witness those themes in formation. From the cover’s fallen heroes to the outro’s cut-off prayer, the project frames art as life-or-death urgency—a young man’s plea to be heard and remembered.

While OD essentially served as Kendrick’s coming-of-age, it also connected him to the wider hip-hop world. J. Cole becoming a fan was the first ripple. In late 2010, Cole praised OD over bigger releases, and that admiration led the two to link up. Cole would later produce “HiiiPower” for Kendrick’s 2011 album Section.80, a collaboration that signaled the rise of a conscious rap vanguard. Even more pivotal was Dr. Dre’s reaction. He stumbled upon the “Ignorance Is Bliss” video and was immediately intrigued. Early in 2011, he tracked Kendrick down, eager to work with the kid from Compton. Kendrick later recalled getting an out-of-the-blue call from Dre’s camp while on tour—he thought it was a prank. It wasn’t. Without OD, that encounter might never have happened. Dre brought him into the studio, tested him on a few tracks (including sessions for the long-rumored Detox), and ultimately co-signed him as the next West Coast star. The kid who idolized N.W.A. suddenly had Dr. Dre in his corner—a passing of the torch OD helped spark. From there, the path accelerated. Within two years, Kendrick released good kid, m.A.A.d city under Dre’s Aftermath umbrella, with the world watching. It traces back to the spark lit by that OD moment that made the good Doctor say, “I need to find this guy.”

In hindsight, OD didn’t just launch Kendrick—it shone a light on the talent around him and laid the groundwork for the dynasty that Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE) would become. The tape plays like a roll call of future stars and collaborators. ScHoolboy Q shows up on the chest-thumping “Michael Jordan,” his animated verse about “ballin’ like Mike” helping establish Q’s identity beyond anyone’s hype-man assumptions. That song’s local traction did real work for Q, marking his shift from TDE sideman to a compelling artist in his own right. Ab-Soul delivers a show-stealing closer on “P&P 1.5” that likely sent curious listeners digging for more; those who did found Longterm 2, a standout that signaled TDE’s talent ran deep. OD also features a young Jhené Aiko on “Growing Apart” and BJ the Chicago Kid singing a Curtis Mayfield/Common interpolation on “R.O.T.C. (Interlude).” In 2010, both were largely unknown prospects; their soulful contributions here turned heads and gave them early shine. It’s striking now to hear a teenage Jhené harmonizing on a Kendrick mixtape long before her own albums went platinum—OD quietly marked first steps for future stars.

Even the lesser-known names mattered. Singer Ash Riser provides atmospheric vocals on “Barbed Wire”; he would later appear on every Kendrick album except good kid, m.A.A.d city, proof of the tight creative circle around K.Dot. Alori Joh brings haunting backgrounds to “Heaven & Hell”; she passed in 2012 but left an imprint on TDE’s story. Behind the boards, Tae Beast, Sounwave, and Willie B—then in-house producers—supplied the backbone. From the dreamy soul of “Opposites Attract” to the menace of “Ignorance Is Bliss,” their work laid sonic foundations for Section.80 and good kid, m.A.A.d city. The only TDE elder absent on OD is Jay Rock, the crew’s eldest member and first to build a major buzz. He doesn’t rap on this tape, but his mentorship and credibility were crucial to TDE’s rise and Kendrick’s growth. In many ways, OD was a showcase for a movement in the making—the moment the world glimpsed Black Hippy/TDE as a collective force. It let the fans meet Kendrick’s “homies, enemies, lovers, and lessons”—the characters and collaborators who would populate his narratives for years.

In the years after OD, Kendrick Lamar reached heights few predicted in 2010—crafting modern classics like good kid, m.A.A.d city, the expansive To Pimp a Butterfly, and the Pulitzer Prize-winning DAMN. His sound and persona shifted with each project, from wide-eyed kid to high-concept auteur to artist-as-author. Yet the roots trace straight back to OD. The introspective storytelling, the socio-spiritual depth, the habit of questioning himself and his environment—it was all there in nascent form. OD echoes through “U” and “FEAR.”, through “The Art of Peer Pressure” and “How Much a Dollar Cost,” and through “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst.” Debut mixtapes are often raw sketches. OD is more than a historical curiosity. This tape still plays as the first bold statement from one of the era’s defining lyricists. It remains wholly hip-hop and committed to lyrical substance. For new fans who arrived later, OD offers a charged listen to the origin of a legend—the moment a 23-year-old declared his ambition. This is where the journey starts, in all its passion and rough-edged clarity. Overly Dedicated may have begun as “just” a mixtape, but it’s a crucial piece of the Kendrick Lamar story—the moment the good kid from Compton first showed he was great.

this is awesome