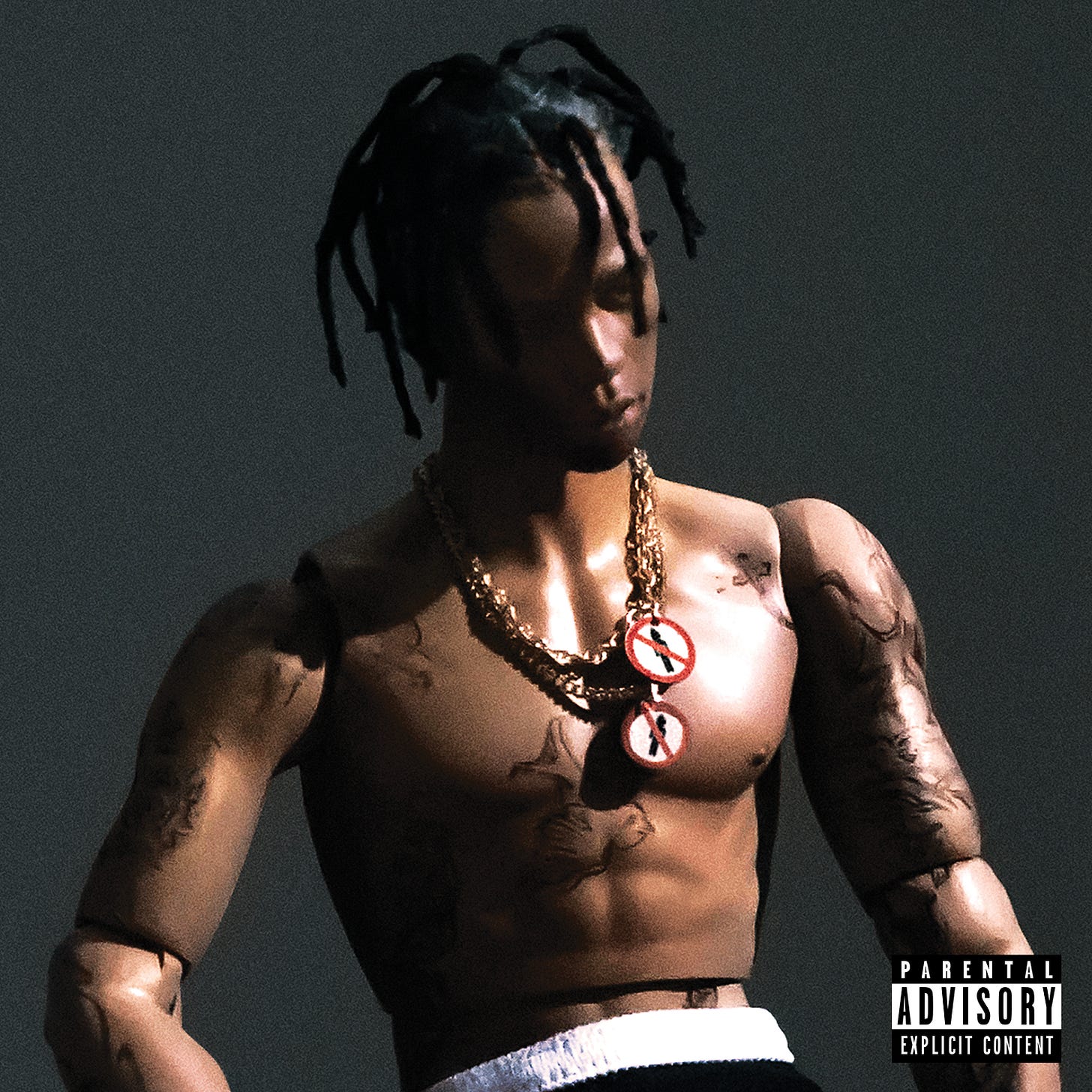

Anniversaries: Rodeo by Travis Scott

We can credit its innovations, call out its imitations, and recognize it as Rodeo that pushed Travis Scott toward hip-hop stardom—bold, flawed, and signal in shaping the lane he would later own.

A 23-year-old Travis Scott stepped out from his mentor’s stage with a debut that felt colossal and familiar at once. Rodeo, long in the making, borrowed the scale of Kanye West’s spectacle—high-budget, high-profile—and translated the My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy strain of maximalism into mid-2010s trap. The songs are lush, layered, dense with interlocking details, and the guest list is meticulously cast. From the shimmering piano coda of the eight-minute “3500” to the two-part suite “Oh My Dis Side,” Rodeo moves like a carnival. The album takes the tropes of luxury rap and oversized production and refits them for its moment—a trap opulence built for the post-Yeezus era.

Scott built Rodeo like a big-tent production. The guest list—Kanye West, Justin Bieber, The Weeknd, Future, 2 Chainz, Young Thug, and others—signals a bid for blockbuster scale. Appearances are placed to heighten the songs’ impact: a crooning Weeknd on the moody “Pray 4 Love,” a scene-stealing Bieber verse on the woozy “Maria I’m Drunk.” Collaborators function like instruments, their distinct energies filling out the mix. The production bench is equally stacked: Metro Boomin and Zaytoven drive the 808s; Mike Dean’s synths smear and swell; Pharrell adds left-turn textures. The result is a dense, high-gloss palette where each track arrives as an occasion, marrying trap’s grit to a cinematic scope usually reserved for rock-star theatrics.

Beneath the bombast, Rodeo lets Scott shapeshift. He toggles between personas—one moment channeling Kid Cudi’s moody melancholia, the next drawing on Young Thug’s elastic cadences. On the second half of “90210,” airy vocals and a brooding tone nod to Cudi’s influence, from humming hooks to confessional undercurrents. When the energy spikes, the free-form ad-libs and slippery phrasing on “Nightcrawler” echo Atlanta’s new school. Even the live anthems carry punk-level adrenaline; “3500” and “Oh My Dis Side” hit with mosh-pit fury, in step with the “rager” persona he honed onstage. Throughout, Auto-Tune is a tool, not a crutch—bending his voice to match the vibe at hand. The approach is openly referential, raising a fair question: are these borrowings the mark of a resourceful tastemaker or signs of an artist still locating a singular voice?

That question shadowed the rollout. As hype swelled, pushback gathered online: was Scott innovating or repackaging the styles around him? Accusations of creative borrowing trailed him—claims that ideas were lifted, aesthetics repurposed, identities composited. Whether fair or not, that doubt followed Rodeo. Its strengths gave both sides ammunition. Stylish and of its moment, yes; yet to detractors, its center felt assembled from borrowed parts.

“Antidote” makes the case both ways. The song began as a loose SoundCloud drop, then was folded into the album after its hook caught fire. Its nocturnal melody, sing-song delivery, and crooning refrain—“Don’t you open up that window, don’t you let out that antidote…”—distill Scott’s appeal: atmosphere first, a sticky chorus, hedonism in soft focus. Some listeners also heard clear echoes of Swae Lee’s high-pitched melodies. With time, the track has become a set-piece at parties and shows, its woozy chorus built for mass sing-along. You can also hear the triangulation at work: melodic Auto-Tune, trap drums, reverbed vocals, all polished to an upscale sheen. Elsewhere, album cuts oscillate between promise and pastiche. “90210” drifts from a dreamy, introspective first half into a grittier back end with distorted guitars and clapping snares—a dynamic arrangement executed with an ear trained by predecessors. Rodeo walks that line: dazzling ideas and stylish moments that captivate, with other artists’ ghosts often audible in the mix.

Lyric craft is where Rodeo shows seams. The energy and atmosphere hit hard, but on solo stretches, Scott leans on simple flexes and stock imagery, and clunkers creep in. On “I Can Tell,” he brags, “Always hit the gas like I broke wind”—a groaner that reads like a freshman-year punchline. It captures where he was in 2015—prioritizing vibe and melody over wordplay. The album isn’t empty of quotables, though. On the menacing opener “Pornography,” amid distorted synths, he growls, “Who do I owe? … No one,” a statement of self-reliance that functions like a mission statement. The paradox is obvious: Rodeo depends heavily on the talent he convenes, even as he insists on independence.

If the pen wavers, the ear doesn’t. Scott’s core skill is curation—of sound, of cast, of mood. Before he was a marquee rapper, he was a beatmaker and arranger in rooms with Mike Dean and the GOOD Music circle, and that studio education shows. Rodeo moves with cinematic flow; songs bleed into each other; his distorted vocal effects become another instrument. On a downtempo interlude, he’ll drench the voice in Auto-Tune; on “Nightcrawler,” he rips it into a serrated hook. The aim is texture and impact. In a period when rap was opening to hazier, psychedelic palettes, that instinct for immersive soundscapes mattered. The record helped push melodic trap further into that space.

The rise behind the music is just as instructive. Scott entered wearing multiple hats—producer, rapper, songwriter—and multiple logos, signing early with T.I.’s Grand Hustle and aligning with Kanye’s GOOD Music. By Rodeo, he had climbed the industry ladder through affiliation and momentum. A friendship with director Mike Waxx (Illroots) led to an introduction to T.I., who not only signed him but also narrates the album’s intro as a public co-sign. From there, Scott linked with engineer Anthony Kilhoffer and found his way into Kanye’s orbit, contributing during the Yeezus era. The album that followed reads like a victory lap for a young hustler who learned how to turn access into art. The liner notes are a roll call. It’s no accident that many high points feature guests in the foreground: Quavo and 2 Chainz bring Southern bite to “Oh My Dis Side,” Toro y Moi floats through “Flying High,” Future pours syrupy menace over “3500.” At times, Rodeo plays like Travis & Friends—a carefully assembled snapshot of mid-2010s hip-hop filtered through his sensibility.

That approach raises the obvious question: how much of Rodeo rests on Scott’s artistry versus the craft and wattage around him? The answer cuts both ways. Charismatic features often seize the spotlight—2 Chainz’s quotables on “3500,” Juicy J’s effortless bark on the same track, the Weeknd and Bieber lending crossover glide. On the flipside, it’s Scott’s taste that assembles and glues these parts. Even when a guest dominates a moment, the haze-and-adrenaline atmosphere remains recognizably his. In that sense, the album is as much cultural orchestration as rapping—one voice threaded through many.

A decade on, Rodeo invites a sharper look. It captures a mid-2010s pivot, when trap went fully mainstream and maximalism ruled. Its fingerprints are audible in the psychedelic, genre-blending trap that followed. Artists who rose after Rodeo—Lil Uzi Vert, 21 Savage, Lil Yachty, among them—worked in a space where woozy atmospherics and heavy drums could share top billing. The idea that a trap album could sprawl and still feel cohesive gained new proof here. Certain cuts have grown in stature. “90210,” with its two-part structure and Hollywood dalliance, sits among Scott’s most beloved deep cuts; “Maria I’m Drunk,” a hazy, illicit ode with Young Thug and Bieber, has its own legend. Party starters like “Nightcrawler” still jolt a crowd, and “Antidote,” derivative or not, remains a carefree trigger for mass release. For many listeners, Rodeo is a reference point and a touchstone in his catalog.

Yet the debut was a launchpad, not an endpoint. Birds in the Trap Sing McKnight leaned deeper into hypnotic, Auto-Tuned melodicism; Astroworld tightened the concept and refined the spectacle. Stack them side by side and the contrast is clear—Rodeo bristles with ideas and occasional indulgence; its narrative—a young rebel chasing rock-star glory—threads through T.I.’s interludes and a handful of reflective moments, but Scott’s lyrical perspective is still coalescing. By Astroworld, the storytelling is sharper and the balance between ego and introspection more secure, while the sound design grows even more grand. The through-line remains the same: adventurous production, cross-pollinated rap subgenres, unabashed rock-show theatrics. Those elements set the stage for later triumphs and influenced peers. The trade-offs are visible too—reliance on borrowed styles and uneven pen work complicate any claim to unimpeachable classic status.

Where does Rodeo land among rap debuts, you may ask? It depends on the criteria. If the measure is cultural influence and a snapshot of its era, the case is strong—the album helped normalize a “psychedelic trap” aesthetic and proved a rapper could play rock-star impresario without abandoning 808s. If the measure is originality of voice and lyrical depth, it falls short of the gold standard. Style often outruns substance, and the lead artist’s identity can blur inside his influences and his guests. The most accurate reading may be this: Rodeo is a dramatic stepping stone in Scott’s evolution, the moment he braided inspiration, ambition, and connections into a formal announcement without fully transcending them. Its legacy is dual. As mid-decade maximalism, it’s still thrilling. As a portrait of the artist, it’s deliberately incomplete—the sound of a talent gathering power, trying on personas in search of the fit. That ongoing debate is itself evidence of the record’s impact. Years later, we can credit its innovations, call out its imitations, and recognize it as the opening chapter that pushed Travis Scott toward hip-hop stardom—bold, flawed, and signal in shaping the lane he would later own.

Excellently said! This album remains a pillar of what it means to curate an album with features and have the right producers for everything. It's an auditory cinematic experience and it doesn't need a concept or skits to create a throughline. The pictures are painted through the music itself and the various atmospheres and soundscapes it creates. With it being a decade old, it doesn't sound "dated" to me which shows it was ahead of its time.