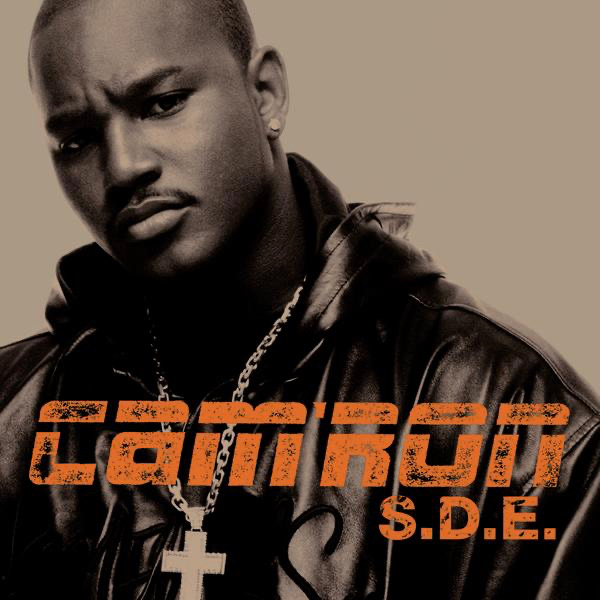

Anniversaries: S.D.E. by Cam’ron

Free of the gloss that trailed Confessions of Fire, he leaned into the underground hero role, and S.D.E. became raw DNA for Dipset’s sound and stance.

“Fuck you… fuck y’all from the very start of this shit,” Cam’ron snarls over the blare of a Millie Jackson sample at the opening of S.D.E. (Sports, Drugs & Entertainment). That profane mantra, looped and chanted in the 1:17 intro track “Fuck You,” burns off any glossy veneer left from his 1998 debut Confessions of Fire. In place of the radio-friendly shine of “Horse & Carriage” or the Usher-assisted club cuts on that first album, S.D.E. opens with a defiant middle finger—a clear pivot toward something more aggressive, street-rooted, and unapologetically raw.

The contrast is deliberate. Bad Boy-era commercial pressures had shaped Cam’ron’s debut; two years later, he tears away those expectations. Over Darrell “Digga” Branch’s stripped-down production, “Fuck You” becomes a mission statement of no-compromise grit. Each “I don’t give a fuck” pushes him further from late-‘90s jiggy sheen and closer to the hard-edged New York resurgence of the era. It’s a brief, brutal opening that sets a tone of confrontation and authenticity, signaling that on S.D.E. he’d sooner alienate pop listeners than betray the streets.

From there, the album lives up to its title, diving headfirst into its three-part world of sports, drugs, and entertainment—the last often taking the shape of crime’s theater. The sports thread runs as autobiographical subtext: Cam’ron was a promising high-school basketball player before street life pulled him off that path. Drugs and the lure of fast money dominate his narratives. Across 19 tracks, he paints a brash tableau of Harlem hustler life—cash hand-offs, gun battles, and sexual conquest—delivered in that languid Harlem drawl that turns boasts into taunts.

On “That’s Me,” he raps, “Imagine me wake up 7:30 for work/I’d rather run the streets 7:30 with work,” flipping “7:30” (New York slang for being crazy) to reject the grind of a 9-to-5. That cynicism—hustling over a paycheck—threads the record. Misogyny is constant, too: women are flattened into objects or schemers. Even the opening skit doubles as a crude joke at the expense of two women who answer his profanity; he dismisses them with the same “fuck you” he throws at everyone else. The onslaught can feel oppressive, sometimes exaggerated to the point of caricature.

There’s a real biography behind the bluster. Cam’ron lost close friends young—his cousin Bloodshed and his partner Big L—and he dabbled in dealing as a teen. Those experiences give weight to the fast-life tales. Still, he often amps them to pulp-comic extremes. “Violence,” with Ol’ Dirty Bastard’s unruly ad-libs, plays like crime fiction: Cam’s verses stack threats and slaying imagery while ODB cackles from the margins. The title Sports, Drugs & Entertainment hints at the blur between reality and performance: street hustle and gangsta rap as parallel arenas that draw on the same survival instincts and bravado. Cam’ron straddles that line with intent. His slow, raspy delivery carries real anger, yet he also knows he’s playing Killa Cam—the larger-than-life figure who can “make a million dollars… spray him, him and him,” as he boasts.

The sound bed, crafted largely by Digga (a fellow Harlem native and Children of the Corn alumnus), nails a minimalist, street-real aesthetic. He handles the bulk of the production, and the choice is pointed: away from the polished opulence of Confessions of Fire and toward unadorned loops and drums—skeletons of familiar songs, stripped to their gritty essence. The beats are never bland. Digga has a knack for flipping recognizable music in off-angle ways. “What Means the World to You” chops The Police’s “Roxanne,” turning Sting’s wail into a hook that’s both incongruous and sticky, a bright ʼ80s shard under brag raps about money, cars, and ice.

On “My Hood,” one of the few tracks produced by Dame Grease, the chorus lifts Edwin Starr’s “War,” transplanting its protest chant into a neighborhood anthem. The choice all but equates Harlem to a war zone and yields one of the record’s most anthemic moments. Elsewhere, “Let Me Know” flips the NFL’s Monday Night Football theme (“Heavy Action”) into a grimy street fanfare. The brass blasts behind Cam’s threats play almost satirically, like prime-time TV scoring his exploits. Time and again, the production mirrors the album’s core dynamic: deadly serious subject matter laced with sly showmanship. Heavy bass thumps, eerie synth flickers, stark soul fragments—these choices keep Cam’s voice centered without drowning it in excess. Familiar samples add melody and nostalgia, drawing listeners in; then the arrangements step back and let him rant, brag, or reflect. Even the beats comment on content: the militaristic chant of “My Hood” positions him as a product and soldier of an endless neighborhood conflict; the “Roxanne” lift in “What Means the World…” turns shallow pursuits into something both catchy and faintly absurd.

Between gun talk and chest-thumping, cracks of self-awareness appear. “Do It Again,” with a young Destiny’s Child on the hook, poses a blunt question: given another chance, would you live life the same way? The chorus—“All those crimes we’ve done, all those times was fun— but would you do it again?”—opens a space Cam’ron rarely enters. In the verses, he counts losses (“I lost brothers, some best friends… we let the hate rise”) and pokes at the root of betrayals (“money is the root of all people,” he quips, twisting the cliché). Then he answers without flinching: “I live my life a thug, live my life with drugs… fuck everybody else, I live my life for Blood.” The line, nodding to his late cousin Bloodshed, recasts his choices as loyalty and grief—acts done for his people as much as for himself.

“What I Gotta Live For” goes darker. Over a somber loop, Cam argues with what sounds like his own conscience. “I ain’t got shit to live for anyway,” he mutters; the voice counters, “Yes you do… you got a lot to live for.” Cam snaps back, “Man, fuck all that I’m sayin’, you live for me then.” The bravado drops. He unloads: “I’m ready to stick the gun to my head and bust a clip… I want the world to see the blood to drip.” He recounts family trauma—a father who called him “a mistake,” a cruelty he admits he repeated to his own daughter—and the grind of poverty: “rent is due, the phone is off, the heat is off.” Even success brings paranoia: “Make a million dollars… why the fuck I gotta pay him, him, and him?” By the refrain, the question “What do I have to live for?” rings as a real plea. The voice that elsewhere sounds untouchable is, here, a 22-year-old shaken by loss, fatigue, and doubt. Placed directly after “Come Kill Me,” the dare-then-despair sequence becomes the album’s emotional peak and its clearest look behind the mask.

Guests widen the canvas and preview the crew that would soon become The Diplomats. Jim “Jimmy” Jones and Freekey Zeekey pop up in skits and posse cuts with unrefined, infectious energy. “Double Up” features the recorded debut of Juelz Santana (credited as “Juelz”), his higher-pitched urgency cutting through Cam’s drawl and hinting at chemistry that would later power Dipset anthems. Jimmy shows up on “Do It Again,” mostly ad-libbing, and pairs with Freekey for the rowdy “Why No.” Neither was polished in 2000, but their raw presence gives the record crew charisma and goads Cam to sharpen his edge. ODB’s chaotic humor on “Violence” jolts the album at the midpoint. Prodigy brings cold-eyed gravity to “Losin’ Weight,” trading drug-world details with Cam. Even Destiny’s Child’s polished harmonies serve the narrative by throwing his gravel and grief into relief. The ensemble approach keeps the album from flattening; it also exposes limitations. Cam’s chosen pacing—slow, deliberate, sometimes slurred for effect—conveys menace, but it can feel one-note next to jumpy ad-libbers or off-kilter crooks. At points, the guests outrun him in energy and variety. More often, they spark him.

One of the strangest moments arrives at the end with “My Hood.” After an hour of uncensored street stories, the song drops whole words and names into silence—not radio bleeps, but dead air. The packaging never labels it a clean version, and the rest of the album is explicit, so the edit lands like a glitch. The simplest explanation is a manufacturing mix-up—an edited take pressed where the explicit should have been. There’s no clear indication of a conceptual reason for the mute bars on the retail album. The effect, intended or not, is memorable. Those silences force the listener to fill in blanks—to imagine the profanity or names removed. After 18 tracks of saying whatever he pleases, the sudden quiet plays like an outside hand on the fader. It’s a fleeting reminder of how quickly “entertainment” can be redacted, and how little is left when a voice built on saying it all is stripped of its sting.

In the years since its 2000 release, S.D.E. has settled into a quiet cult status. It opened at No. 14 on the Billboard 200—a step down from the gold-certified debut—but it gave Cam’ron something more durable than a crossover single. It locked in his identity and his core audience. Free of the gloss that trailed Confessions of Fire, he leaned into the underground hero role, and S.D.E. became raw DNA for Dipset’s sound and stance. You can hear it in what followed: the unapologetic Harlem bravado of Diplomatic Immunity, the eccentric humor that runs through Purple Haze, the way Cam and his crew turned pink furs and neighborhood slang into global currency. S.D.E. is the blueprint in spirit if not in name.

It’s also a transitional record—overshadowed by later highs, but pivotal. Cam parted ways with Epic soon after the album’s release, frustrated with its push, and moved to Roc-A-Fella by 2001, where Come Home with Me vaulted him into a different tier. In hindsight, S.D.E. sits between eras: not the big-budget bounce of his Roc-A-Fella period, and far from the shiny-suit mold. That in-betweenness likely slowed its early reception; coming back to it now, the draw is plain. The grit isn’t a pose. He sounds hungry and unbowed by industry expectations, building a foundation, brick by brick, for what would become Dipset.

After all, Sports, Drugs & Entertainment holds a singular place in Cam’ron’s catalog. It’s flawed, ferocious, and revealing—too gritty for the masses, too central to be forgotten. If Confessions of Fire was him learning the industry’s rules and Come Home with Me was him mastering them, S.D.E. is the rebellion in between, the record where he chose to give it to listeners raw and uncut. That gamble didn’t make a blockbuster. It forged Killa Cam. Today, fans cherish S.D.E.for what gatekeepers once found troublesome: unvarnished, uncompromising grit. Listen closely and you hear an artist freeing himself—sometimes stumbling, sometimes soaring, never surrendering his voice. The lasting lesson is simple: play to your strengths. Cam’ron’s strength was the truth of his streets, told boldly.