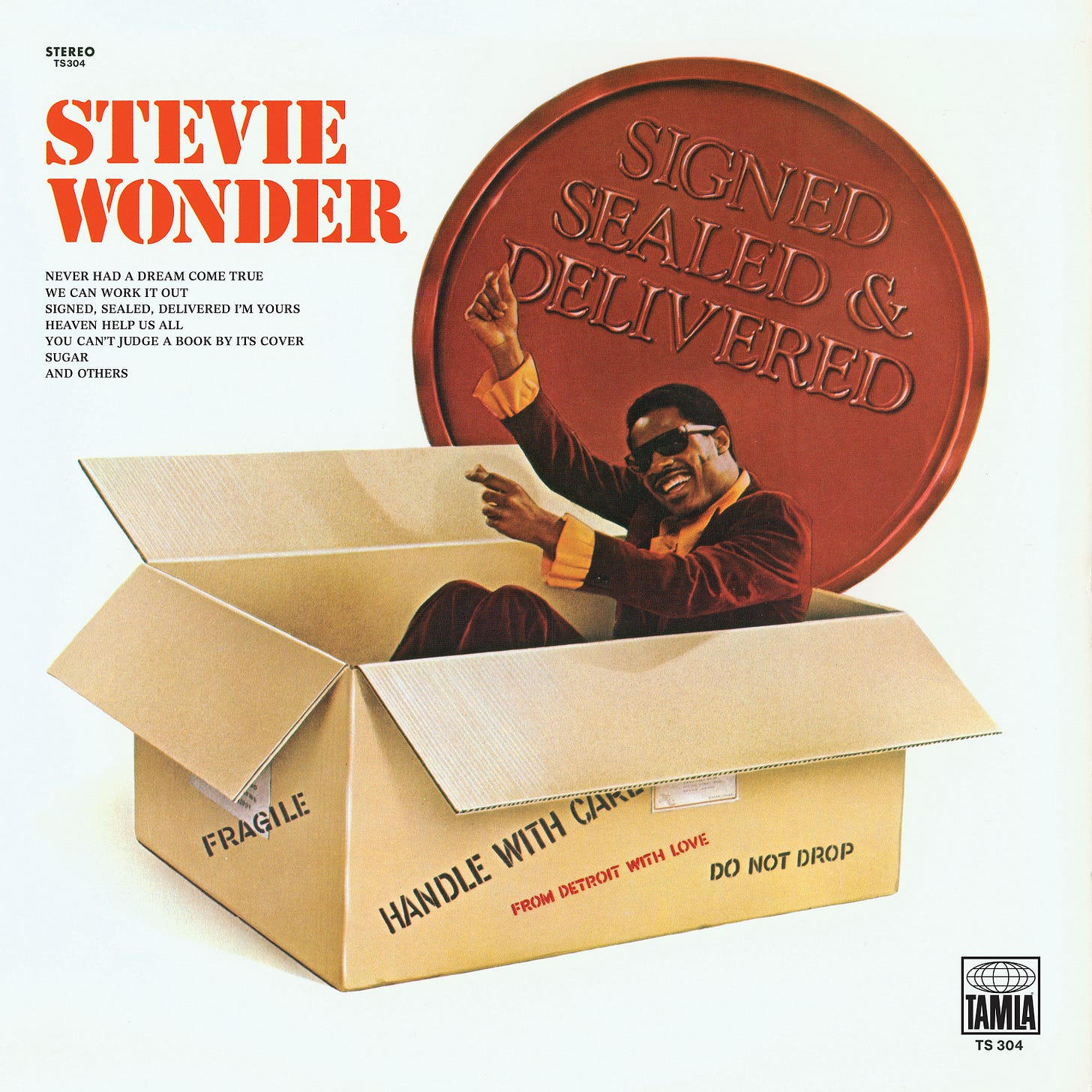

Anniversaries: Signed, Sealed & Delivered by Stevie Wonder

A 20-year-old Stevie Wonder released Signed, Sealed & Delivered, an album that captured an artist at a crossroads. It isn’t his magnum opus, but it’s the spark that made a child star a revolutionary.

Stevie Wonder was no longer “Little Stevie,” the teenage Motown prodigy with a string of joyous hits; he was a young Black man on the cusp of creative independence, eager to spread his artistic wings. This record, his twelfth studio album, marked the moment Stevie began to push back against Motown’s hit-factory formula. Even as he continued to deliver infectious, radio-ready songs, Wonder used Signed, Sealed & Delivered to explore deeper themes and new sounds. From today’s vantage point, the album is the bridge between Stevie’s 1960s pop-soul persona and the groundbreaking freedom of his 1970s masterpieces.

It arrived at a time when the changing currents of soul and pop were testing Motown’s smooth hit-making machinery. The late 1960s had seen artists like Marvin Gaye, The Temptations, and Sly & The Family Stone infuse social commentary and psychedelic funk into Black music. Stevie Wonder absorbed this climate. Though just out of his teens, he’d been a Motown star for years, and he felt the itch to assert more control over his music. On this album, Wonder secured his first producer credits, co-producing several tracks and even solely producing two of them. He also co-wrote seven of the album’s twelve songs. Signed, Sealed & Delivered was the first real evidence that Stevie was not content to be a cog in Berry Gordy’s machine.

Wonder’s career to this point was steeped in the contradictions of Black excellence under white corporate oversight. Motown, that gleaming Detroit empire, had elevated Black artists to crossover stardom but often at the cost of creative autonomy. Songs were workshopped by teams, arrangements dictated by house bands like the Funk Brothers, and themes kept light, lovelorn, and danceable to appeal to white audiences. Wonder, a prodigy who could play harmonica, drums, piano, and more, chafed against this. He’d already experimented with covers and originals that hinted at depth—“For Once in My Life” in 1968 was born out of personal struggle—but Signed, Sealed & Delivered was where he asserted control. He co-wrote most tracks, played multiple instruments, and even enlisted his then-wife, Syreeta Wright, as a collaborator. The album’s production, shared with Henry Cosby, introduced early electronic elements: synthesizers peeking through the mix, clavinet-like tones foreshadowing the Moog-heavy innovations of later works. Yet, it didn’t abandon Motown’s sheen, but polished it with purpose, balancing commercial viability with artistic nudges toward something freer.

The title track, “Signed, Sealed, Delivered I’m Yours,” explodes out of the gate like a love letter stamped with urgency, its enduring power lying in how it marries infectious joy to layered vulnerability. Clocking in at just over two and a half minutes, it’s a masterclass in economy: horns blare triumphantly, Wonder’s voice soars with gospel fervor, and the rhythm section—anchored by James Jamerson’s bass—pulses with that unmistakable Motown swing. It’s a redemption tale, Wonder confessing past mistakes while pledging total surrender. “Like a fool I went and stayed too long/Now I’m wondering if your love’s still strong,” he sings in the opening verse, his delivery raw yet rhythmic, evoking the pain of youthful folly. The chorus—“Signed, sealed, delivered, I’m yours!”—borrows from legal jargon, a metaphor for unbreakable commitment, but Wonder credited his mother, Lula Mae Hardaway, for the phrase, turning it into a familial nod amid romantic plea. Co-written with Wright, Garrett, and Hardaway, the song’s genesis reportedly stemmed from Wonder’s own relationship ups and downs, a theme that resonates today in an era of viral breakup anthems and therapy-speak playlists. Musically, it’s prophetic: Wonder overdubs his vocals for a call-and-response effect, hinting at the multi-tracking wizardry he’d perfect on albums like Innervisions. Its legacy? Sampled by everyone from Blue (with Elton John) to modern hip-hop producers, it’s a staple in weddings, commercials, and Obama-era nostalgia—remember Michelle quoting it in her speeches?

Wonder’s inspired cover of the Beatles’ “We Can Work It Out” further illustrates his knack for reimagining pop through a Black lens, injecting funk where Lennon-McCartney offered folk-rock restraint. The original, from 1965’s Rubber Soul, was a mid-tempo plea for reconciliation, Paul’s optimism clashing with John’s cynicism. Wonder flips it into a high-energy romp, speeding up the tempo, layering clavinet stabs and handclaps, and transforming it into a soul sermon. His version opens with a harmonica riff that’s pure Wonder—playful, bluesy—and his vocals stretch the melody, adding ad-libs like “Come on, baby!” that infuse urgency. He stays faithful: “Think of what you’re saying/You can get it wrong and still you think that it’s alright,” but the delivery shifts the tone from British reserve to echoing the civil rights mantra of persistence. SS&D is seen as a bridge between Motown’s cover tradition—think the Supremes doing Beatles tunes—and Wonder’s emerging originality. In retrospect, this track foreshadows his ‘70s covers like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” where he wove social commentary into borrowed frameworks.

Diving deeper into the album reveals cuts that showcase Wonder’s growing depth, like “Never Had a Dream Come True,” a poignant ballad that blends heartache with hope. Co-written with Wright and Cosby, it’s a re-recording of a 1968 track, but here it’s refined, Wonder’s piano anchoring a string-swept arrangement. The lyrics unfold as a confession of unrequited love: “I never had a dream come true/Till the day that I found you,” he croons, the melody ascending on “dream” like a sigh of longing. The bridge intensifies—“Even though I pretend that I’ve moved on/You’ll always be my baby”—revealing emotional layers, a vulnerability rare in Motown’s upbeat catalog. Musically, it’s transitional: traditional orchestration meets Wonder’s harmonic experiments, chords borrowing from jazz.

Even more overlooked is “I Can’t Let My Heaven Walk Away,” a mid-tempo gem that delves into relational turmoil with subtle electronic flair. Wonder’s clavinet-like keys bubble under the surface, an early nod to the synth-driven sound he’d unleash on Talking Book. It’s a desperate plea: “I can’t let my heaven walk away/‘Cause if she leaves me, what would I do?” The verses build tension—“We’ve had our ups and downs, but love’s still around”—culminating in a chorus that’s both catchy and cathartic. Co-written with Don Hunter, it reflects Wonder’s marriage to Wright, blending autobiography with universal themes. The breakdown in the bridge, where instruments drop out for vocal harmonies, creates intimacy, Wonder’s voice cracking with emotion. This track exemplifies his balance: radio-friendly structure masking deeper commentary on commitment in turbulent times. In the context of 1970, amid rising divorce rates and feminist awakenings, it subtly nods to social shifts without overt preaching.

Throughout Signed, Sealed & Delivered, Wonder masterfully balanced commercial appeal with artistic freedom, a tightrope walk that defined his career pivot. Tracks like “Sugar” and “Heaven Help Us All” (a gospel-infused call for unity, later covered by Ray Charles) introduce social edges—prayers for peace amid war—while “You Can’t Judge a Book by Its Cover” delivers funky wisdom with Bo Diddley rhythms. He didn’t abandon hooks; every song clocks under four minutes, primed for AM radio. Yet, by playing most instruments himself on several cuts and incorporating Moog-like sounds, he signaled independence. Motown resisted—Gordy favored formulas—but Wonder’s success forced concessions. By 1971’s Where I’m Coming From, he’d negotiate full control, leading to the synthesizer symphonies of Music of My Mind and beyond.

This album’s influence rippled through Wonder’s breakthroughs: the electronic experimentation bloomed in “Superstition,” the social commentary in “Living for the City.” It paved the way for his ‘70s masterpieces—Talking Book, Innervisions, Songs in the Key of Life—where he became a one-man band, addressing race, love, and politics with unparalleled depth. In the broader early ‘70s soul and pop landscape, Signed, Sealed & Delivered sits as a linchpin. As Marvin Gaye released What’s Going On in 1971, questioning America’s soul, Wonder’s work offered a poppier counterpart, proving social awareness could coexist with hits. It paralleled Sly & the Family Stone’s There’s a Riot Goin’ On, blending funk with introspection, and influenced Earth, Wind & Fire’s orchestral soul. Pop-wise, it prefigured the singer-songwriter boom, Wonder’s multi-instrumentalism echoing Paul McCartney’s solo work. In Black music culture, it marked a shift from Motown’s crossover polish to Afrocentric innovation, empowering artists like Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack to blend genres.

Wonder, now 75 and a global icon, saw his early pushback yield Grammys, activism (his Martin Luther King Day campaign), and timeless relevance. Signed, Sealed & Delivered isn’t his magnum opus, but it’s the spark—the moment a child star became a revolutionary, sealing his fate as soul’s eternal wonder.