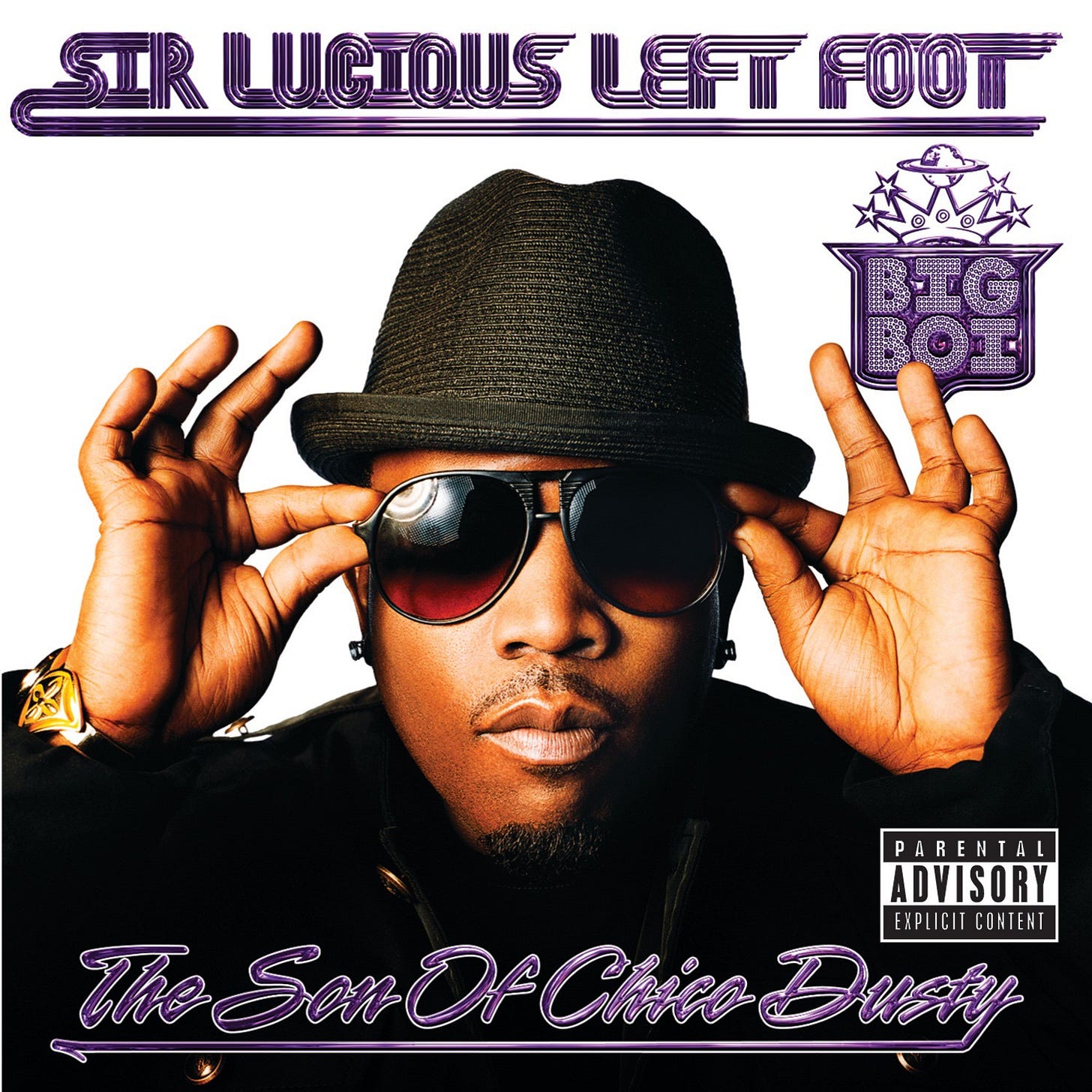

Anniversaries: Sir Lucious Left Foot: The Son of Chico Dusty by Big Boi

Big Boi’s left foot forward was a giant leap, and its funky footprint in hip-hop history is undeniable. It proved that the man who helped give us classics pushed the envelope even without his partner.

Being one half of the legendary OutKast, Big Boi had watched his solo debut delayed and even rejected by Jive Records, who infamously deemed the album “a piece of art” they didn’t know how to market. Frustrated by corporate Jedi mind tricks and attempts to force an OutKast reunion, Big Boi jumped ship to Def Jam to finally release Sir Lucious Left Foot: The Son of Chico Dusty on his own terms. Notably, Jive even barred André 3000 from appearing on the album, cutting planned collaborations and leaving Big Boi to prove he could stand “me, standing alone” without his more flamboyant partner. Burdened with nearly three years of false starts, label squabbles, and sky-high expectations, what we got is an album that’s so vibrant and inventive that critics immediately hailed it as “one of the best rap records of the year, full of vitality and bounce,” which was well worth the wait.

For years, OutKast’s dynamic was painted in stark contrasts. André as the eccentric visionary in wild costumes, Big Boi as the grounded street general holding down the groove. He’d long been the “earthy, street-level anchor to André’s spaced-out visionary, the guy responsible for securing the group’s cred when André was trying to invent new colors,” as one reviewer put it. In other words, Big Boi was respected but often taken for granted; his partner’s star power overshadowed the reliable player. Sir Lucious Left Foot forcefully upends that narrative. From the first tracks, it’s clear Big Boi isn’t content to play second fiddle to anyone’s avant-garde. “He’s less pimp than craftsman, packing more style—and more substance—into his four-minute songs than other rappers deliver in an entire album,” Rolling Stone observed of his performance. Big Boi’s lyricism is playful yet razor-sharp; his inimitably slick, speedy flow slices through beats with a confidence that demands a reevaluation of his artistry. If past OutKast albums cast him as the dependable “street don” next to André’s flights of fancy, Sir Lucious proved Big Boi could be the visionary too. “Expect Sir Lucious Left Foot to change those conversations,” Pitchfork proclaimed, noting we hadn’t heard a major-label rap album “this inventive, bizarre, joyous, and masterful in a long time.”Big Boi stepped out of André’s shadow and into his own spotlight, delivering an eclectic masterwork that many felt rivaled OutKast’s best work.

The years of delay and Andre’s enforced absence ultimately shaped the album’s very character. Rather than dilute his creativity, the setbacks seemed to energize Big Boi. He’d stockpiled songs since 2007, tinkering in Atlanta’s Stankonia Studios to get everything just right. Some topical lyrics even reveal their long gestation, sly jabs at the industry that “sound like they were written years ago,” but there’s no bitterness weighing down the music. If anything, Big Boi channels his frustration into fuel. He pointedly avoids the jaded tone one might expect from an OG rapper fighting label drama; Sir Lucious is “blissfully free of both old-man hectoring and drug-rap nihilism,” overflowing instead with youthful exuberance. “They almost tried to kill my career with that waiting,” Big Boi said of the delays, yet the album sounds utterly alive, never tired.

Deprived of André 3000’s presence, Big Boi doubled down on his own strengths and his Atlanta roots. He invited a circle of his Dungeon Family compatriots and kindred spirits, from Sleepy Brown and Joi to George Clinton and Janelle Monáe, to contribute, crafting a collaboration-heavy set that “almost make up for the Jive-enforced absence of André. As L.A. Times critic Ann Powers noted, Big Boi spent the interim “hanging with his people, getting stronger, turning plans into action.” The resulting record doesn’t feel like a compromised solo effort missing a piece; it feels like a celebration of Big Boi’s extended musical family and a showcase for his own expansive imagination. “Though his partner is absent, this sounds and feels like another OutKast experience—a welcome one,” wrote the A.V. Club, affirming that Big Boi had more than filled the void.

The debut is a kaleidoscopic funk-rap odyssey, a far cry from any label-mandated cookie-cutter. Big Boi described it as “a funk-filled extravaganza… layers and layers of funk with raw lyrics”, and he wasn’t kidding. The album throbs with Southern hip-hop’s bass-heavy 808 bounce, yet rockets off into myriad genres, often all in the same track. One moment you’re in an ATL strip club, the next in outer space. Critics marveled at the dense, unpredictable production: “New melodic elements flit in and out of tracks just as you start to notice them, and there’s a lot going on at any given moment,” Pitchfork noted. Indeed, Sir Lucious “explodes with ideas at every turn,” gliding and twitching with a delirious urgency as if bursting to make up for lost time. The dominant flavor is P-Funk futurism—“1980s synth-funk signifiers” are everywhere. Squelchy synthesizers roam and glimmer; old-school talkboxes mutter and blurt robotic hooks from beyond; basslines wobble with gut-rumbling vigor.

Yet these tracks are no retro pastiche or “stoned miasmas” à la 80s revivalists; they’re “itchy and fleet-footed,” restlessly modern in their assembly. Big Boi draws from a wide range of influences—funk, soul, crunk, electro, rock, dubstep, and even orchestral classical fanfare—but blends them into a cohesive party. “It’s eclectic, electrifying, eccentric and more than a little bit ludicrous,” one reviewer laughed, “but Sir Lucious’s ambition is as infectious as its madness is dazzling.” In other words, this album is a wild and fun ride. Despite the experimental streak, the overall mood is unmistakably upbeat and joyous. Nearly every song has a spring in its step (if not a small jetpack) propelling it forward.

Big Boi’s own rapping contributes greatly to that kinetic feel. He darts in double-time across even the slowest beats, his flow “inimitably slick and speedy”—turning his verses into another rhythmic instrument that keeps the energy high. As Sasha Frere-Jones noted, Big Boi is never a laid-back rapper, clichés about Southern drawl be damned: he’s “wide-awake,” packing his rhymes with tongue-twisting wordplay and unpredictable cadences. Sixteen years into his career, he was still coming up with “dizzy combinations of words” and delivering them with the hunger of a newcomer. All of this combined to make Sir Lucious Left Foot a “state-of-the-art Southern-fried party-funk album”, one bursting with “surface charm” and delightful surprises at every turn.

Nowhere is the album’s inventive spirit clearer than on its show-stopping single “Shutterbugg.” Co-produced by Big Boi and Scott Storch, “Shutterbugg” hits like a time-warped boogie jam beamed from 1988, yet it’s utterly fresh. Over a rubbery Cali funk bassline and snapping snares, Big Boi lets loose a deep-throated robo-hook, courtesy of a talkbox, that practically rattles your skull. His adventurous duality shines on “Tangerine,” perhaps the album’s most intriguing stylistic hybrid. The track plays like a mood ring, constantly shifting color. On the surface, it’s a slinky Southern strip-club jam, built on a slow-rolling, body-moving beat, but lurking beneath is something delightfully bizarre. On “Follow Us,” Big Boi tackles the rap-rock crossover trope and turns it on its head. The song features Atlanta alt-rock band Vonnegutt, whose lead singer provides a big, anthemic hook, a soaring chorus that wouldn’t sound out of place on modern rock radio. Despite its relaxed, mid-tempo groove—sleepy keyboards and a rolling bassline that evoke a summer BBQ vibe—“Back Up Plan” is punctuated by an arsenal of playful sounds. The Organized Noize-produced track finds room for everything: “cheerleader chants, disembodied grunts, a weird little synth whistle, processed funk guitar, orchestra hits, [and] frantic scratching,” all layered into one laid-back banger

A major reason Sir Lucious Left Foot works so brilliantly is Big Boi’s willingness to embrace collaborators’ wildest ideas. He was always the type to share the spotlight (OutKast itself was a study in creative chemistry), and here he gathers an impressive roster of producers and guests, not to dilute his vision but to enhance it. The album essentially plays like a producer’s playground, with Big Boi as the ringmaster, egging everyone on. Longtime allies Organized Noize anchor several tracks, bringing their Atlanta funk wizardry to the table—the Dungeon Family fingerprints are all over the album’s thick grooves and soulful undercurrent. But alongside them, Big Boi recruited an eclectic mix of beatmakers with the likes of Salaam Remi, Scott Storch, Lil Jon, and even André 3000 (as a producer on one track). At first glance, these names didn’t all scream cutting-edge in 2010. Storch and Lil Jon, for instance, were mid-2000s hitmakers whose stars had faded by then. Yet Big Boi saw an opportunity.

He seemed to give each producer free rein to get weird. Storch’s contribution “Shutterbugg” is deliriously funky and off-kilter, and Big Boi pushed it further by literally bringing his band in to jam over it, layering live guitar and talkbox until the beat was dripping with P-Funk flair. Salaam Remi’s “Follow Us” has already seen a rock hook turned into electro-dancefloor gold. Lil Jon, best known for crunk anthems, was invited to produce “Hustle Blood,” a steamy, bluesy slow jam with live guitar and organ—miles away from his usual bark, showing Jon’s versatility at Big Boi’s behest. Even André 3000 quietly chips in behind the scenes, crafting the beat for “You Ain’t No DJ,” a squelchy, futuristic head-nodder that he and newcomer Yelawolf tear apart. Across the board, his curatorial vision is vindicated by trusting these collaborators and pushing them outside their comfort zones; he concocted a rich variety of sounds. Big Boi’s left foot forward was a giant leap, and its funky footprint in hip-hop history is undeniable.