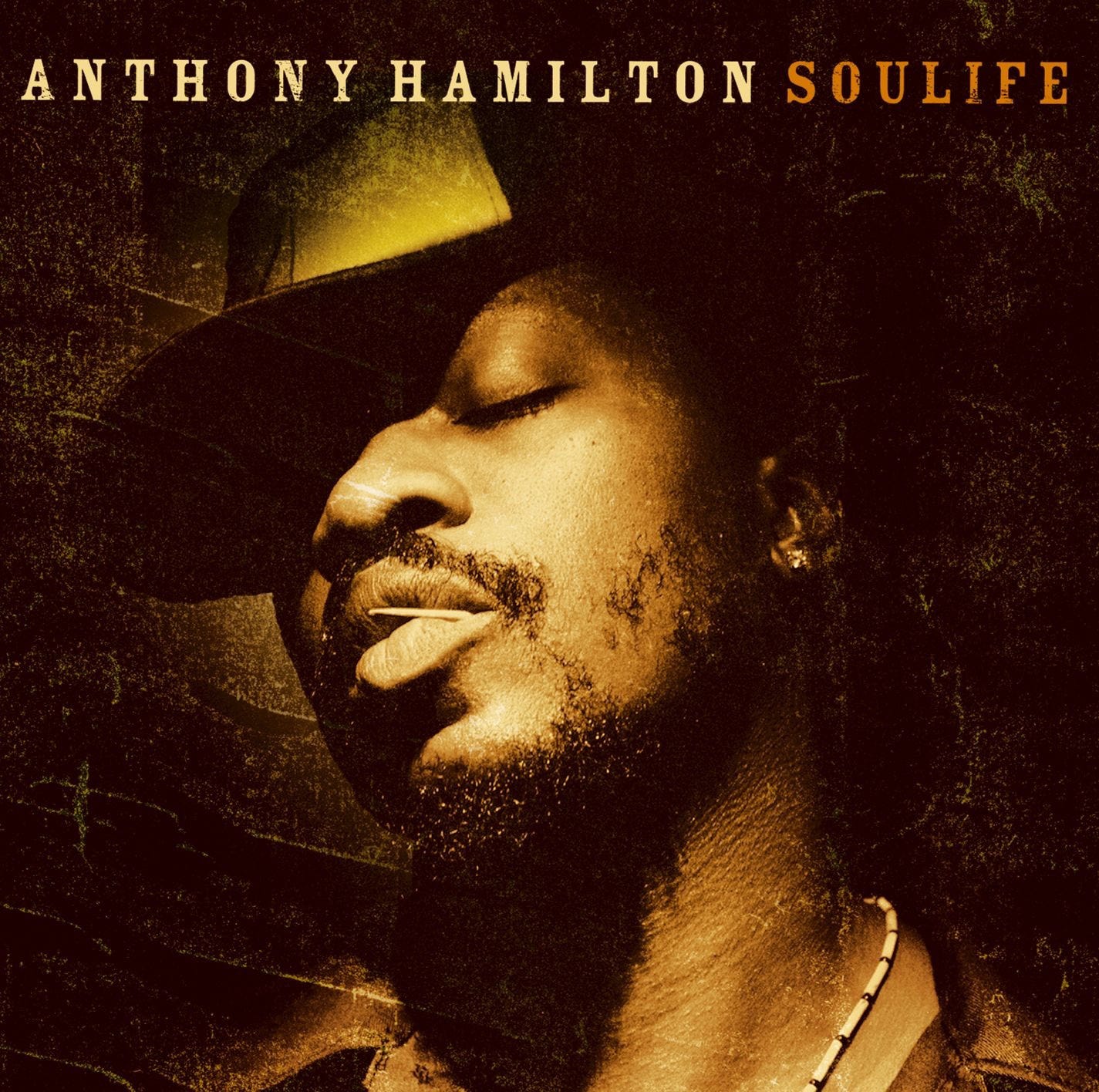

Anniversaries: Soulife by Anthony Hamilton

Soulife holds space in Anthony Hamilton’s catalog not simply as a curiosity or a compilation, but as an alternate axis. It stands beside his later work as both precursor and companion.

A memory stirs when you imagine those cramped L.A. studios around 1999, a young Anthony Hamilton laboring in between sessions—how his voice, raw and earnest, reached for some permanence even before any release was guaranteed. That was the Soulife period: a small independent label in Los Angeles, operating under hope and constraint, where Hamilton cut tracks meant—at least initially—to define a second studio album. But fate had other plans. Soulife folded before the project ever saw the light of day. The vocals, the takes, the unfinished mixes sat in vaults, half-finished. It was Atlantic and Rhino who, years later, would salvage and reassemble this body of work, reshaping it into the 2005 compilation we now call Soulife.

That sense of an album born from rescue is audible in every corner: you hear the original sessions—in their intimate, sometimes fragile presence—and you hear the polishing, the re‑overdubs, the small adjustments meant to render them whole. What’s surviving in that balance is Hamilton’s voice: his signature warmth, the subtle grain in his vibrato, the way he hovers between grit and silk. Whether on a track largely left intact or one nudged through modern touch-ups, you sense the same emotional core—the impression of someone singing not to prove technique but to lodge feeling into your chest. From this vantage, there’s a peculiar tension in Soulife. On one side, the more polished tracks (or polished-up ones) with a cleaner sheen; on the other, moments where arrangements breathe and loosen, leaner in instrumentation, where Hamilton’s voice carries more weight because fewer musical elements compete. Fans who gravitated to Comin’ From Where I’m From (2003) often point to its earthier, sparser moments, where the backing band steps back and the story rides on the singer alone.

In Soulife, that contrast is alive: some tracks feel “produced for a label,” while others feel like discoveries from a rehearsal room, unguarded and vulnerable. Take “Georgie Parker,” the heartbreaking centerpiece whose first notes feel like an invocation. From the breath before the verse begins, the pain is already there, coiled beneath Hamilton’s timbre. The drums arrive—not loud, but deliberate—with a step that seems measured, like someone walking into a truth. His phrasing on “I still see Georgie, walking on that porch in May” (or whichever image he evokes) is so unforced you forget you’re hearing a recorded performance. It sinks into your subconscious. When the chorus arrives, his voice cracks slightly, and the music loosens—strings or keys swell, but never drown him. And when it ends, it doesn’t so much resolve as linger, like an aftershock. You close your ears, and the moment persists.

Elsewhere, “Love and War” carries a different weight. Already known to some from its appearance on the Baby Boy soundtrack (with Macy Gray), it arrives here with fuller context. To hear it within the album’s domain is to catch a thread: that this is not a song tacked on, but one of the pieces in a broader mosaic. The duet with Macy is gentle but firm; the counterpoint in her voice and his feels conversational. The production here is a bit more gilded than some of the dustier tracks, but it does not lose the emotional tether: every harmonic turn, every sustained note, feels like a negotiation between tenderness and strife. It reminds you that Hamilton’s voice can expand beyond solitude, that he can converse, share space. And then some tracks play in the subtle midground, where he’s sometimes accompanied, sometimes soloing, but always present. On “I Cry,” the sparse arrangement gives room for the sobs in his voice, the unforced breaks in his phrase, the creak of emotion. You feel the room around him. “Clearly” offers a lighter pulse—keyboard lines, gentle guitar work—that allows him to dance over the groove without losing gravity. The keyboard flourishes are delicate but expressive: a soft chordal pad here, a chord inversion there, a little melodic tug that tugs your ear toward what should be heard next.

“Day Dreamin’” brings a warm swagger. The beat is lazy but steady, the electric guitar with wah just distant enough to shade some texture, the keyboards coloring corners. When Hamilton slides into the chorus, you hear a voice comfortable in its register, grounded yet reaching. “Ball and Chain” is heavier, where its lyrical weight meets an arrangement that carries subtle tension—drums with snap, guitar that arcs, perhaps a bass run that isn’t flashy but purposeful. These are songs that flirt with R&B, neo‑soul, but are anchored in the sensibility of voice first, arrangement second. “Ol’ Keeper” feels almost like a conversation—quiet, paced. The dusty beat (or a beat that sounds dusty, meaning not perfect, with character) gives the impression of a hallway echo. The production doesn’t camouflage nuance: you hear the slight bleed of instruments, the room tone, the edges. In that way, Soulife sometimes shades into what later Hamilton fans have come to treasure: the raw spaces where voice and story live.

This compilation doesn’t feel derivative or a footnote; it feels like a parallel origin. It’s as if we’re hearing the hidden scaffolding of a career more than a retrospective: the rough sketches that, in time, walked into the fully realized canvases of Ain’t Nobody Worryin’, The Point of It All, What I’m Feelin’, and beyond. Its place in his catalog is liminal—neither debut, nor peak, but a bridge between the unheard and the canonized. That contributes to its aura: every listen is excavation. Put Soulife next to Comin’ From Where I’m From, and the contrast is alive. Comin’ came after the breakthrough of “Po’ Folks,” riding momentum, building identity. Soulife is older material, antecedent material, but one hears in it seeds of what would blossom in Comin’. The more stripped moments of Comin’—when just piano, or guitar, or minimal drums support Hamilton’s lines—feel like echoes of what Soulife allowed. Yet Soulife sometimes presses forward with fuller instrumentation, offering alternate versions of the voice-in-space formula. This alternation enriches our understanding of where Hamilton wasn’t just refining one model of sound, but was testing multiple registers of expression, and Soulife records many of those auditions.