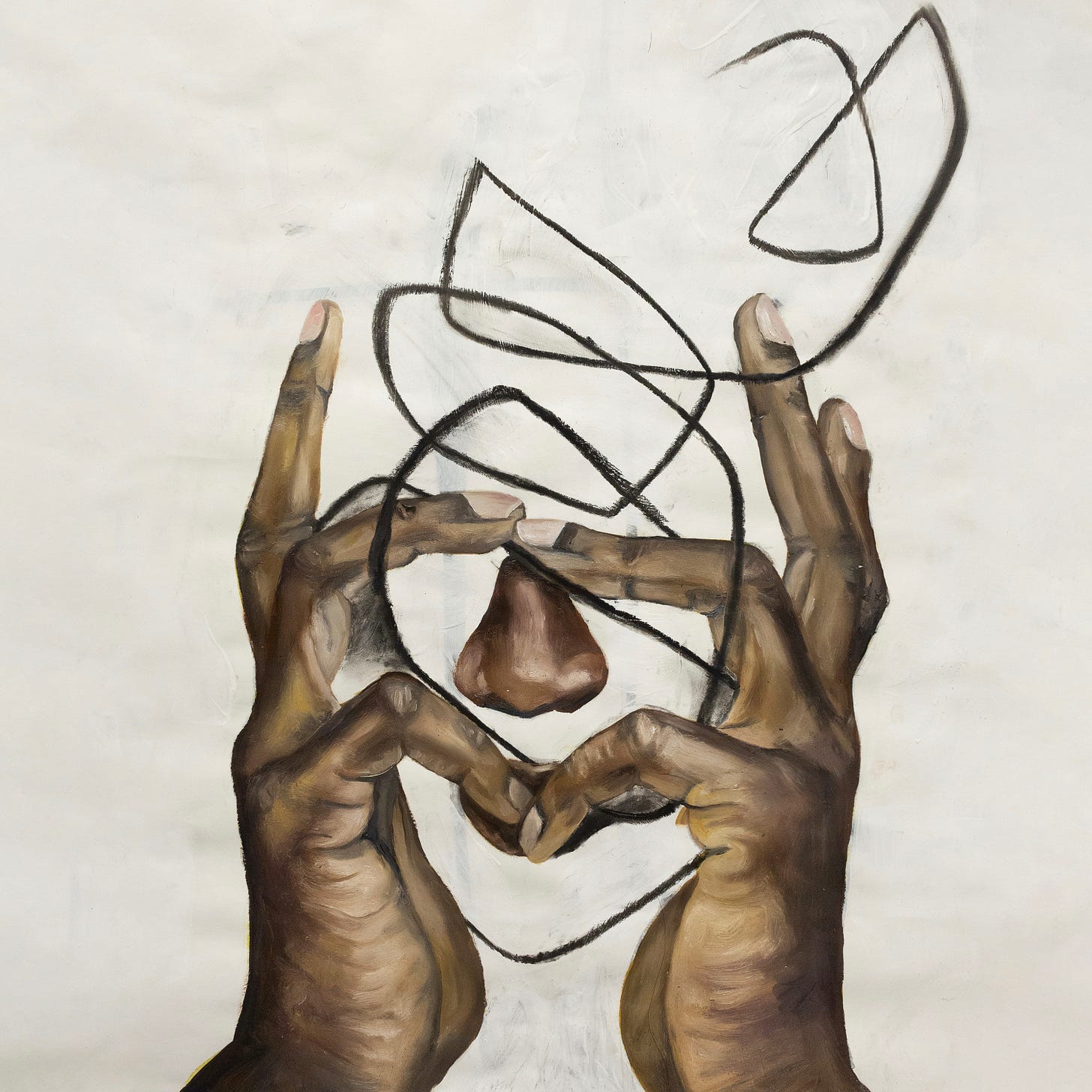

Anniversaries: Streams of Thought, Vol. 3: Cane & Abel by Black Thought

Vol. 3 builds on the foundations of its predecessors and then bursts through the ceiling, revealing new rooms in the house that Black Thought built. It’s both a mourning hymn and a battle cry.

The third installment of Black Thought’s solo series arrived in the middle of turmoil. Streams of Thought, Vol. 3: Cane & Able was originally slated for July 2020, but the death of the Roots co‑founder Malik B. in late July shook the band. The record was pushed back three months and finally released on October 16, 2020, so even its timing bears the weight of mourning. Volumes one and two of Streams of Thought were relatively short, constructed around producers 9th Wonder and Salaam Remi; Vol. 3 is 34 minutes long, marking the project’s growth from concise lyrical demos into a self‑contained album. In the delay between July and October, the pandemic’s claustrophobia, America’s political gaslighting, and the specter of police brutality seeped into the music. The short introduction “I’m Not Crazy (First Contact)” is a fever dream of swirling sirens and droning synths that addresses police harassment and moral panic. Its tension hangs over the record, a reminder that the world outside the studio is on fire.

While the title Cane & Able reads like a biblical pun, it also speaks to the album’s creators. In explaining the subtitle, Black Thought noted that the producer Sean C’s last name is Cane, and he considers himself “one of the most able MCs”; the phrase, therefore, nods to ability, a sign of the times, and “original sin.” Thought’s wordplay points to the partnership that undergirds the album. Sean C—born Delano Matthews—handles the bulk of the beats, with additional seasoning from LV, Sal Dali, and Marvino Beats. Unlike the patchwork feel of the first two EPs, this record sounds like one producer’s vision. Thought praised Sean C for being economical and leaving room for vocals; the producer’s beats are cut from the same cloth as his own hip‑hop ethos, built on New York boom‑bap. Sean C and LV had previously worked with the Hitmen crew, but for Cane & Able, they adopt a murky, ominous palette reminiscent of the darkest Madlib or Alchemist beats. Those textures fit the urgency of Thought’s rhymes and the uneasy mood of 2020.

The album opens with “State Prisoner.” Military‑style snares and chopped piano loops ratchet the tension while Thought unspools a barrage of couplets about mass incarceration, the profit motives of private prisons, and the intergenerational trauma of systemic racism. Over drums that resemble marching feet, he boasts that “I’m the son of the slums with my hair in locs/The energy that flows in the air from Pac,” then pivots to lament that the system is designed to “make a nigga call his father’s name.” The hook—“I am not your prisoner”—is delivered like a doom‑laden chant, hinting at both the literal cages and the mental shackles he seeks to break. Within two minutes, the tone is set: this volume isn’t just a lyrical exercise but a state‑of‑the‑union address.

Aggression gives way to introspection on “Good Morning.” The production is built around a relentless drum pattern, siren‑like synth swells, and crisp piano stabs, giving the song the feel of a city under siege. Black Thought invites Pusha T and Killer Mike to the cypher while Swizz Beatz provides a not-so-needed hook. The three rappers trade verses like heavyweights sparring. Pusha paints a picture of a hustler’s discipline; Mike positions himself as a 21st‑century Mansa Musa, rapping: “How you worship a God and you worship a man?/I was God in the flesh before I drove a Mulsanne/Five keys of gold sitting on my neck in the frame/Surrounded by Black women, West African king.” Thought responds with barbed couplets about media manipulation and the perpetuation of generational wealth. The interplay shows how Sean C’s beat holds space for each voice without being crowded. The track serves as a summit meeting of insurgent MCs, each channeling rage into intricate wordplay.

Between these lyrical pummelings are brief sketches that tether the record to Thought’s personal journey. “Magnificent”—a title that recasts a brief interlude from the track list as an understated dedication to artistic growth—finds Thought meditating on metamorphosis. He likens himself to Hajj Malik el‑Shabazz (Malcolm X) rising from Detroit Red and warns would‑be challengers: “Don’t make me burn your wings off like the Icarus / The Lord take away the same thing he give us/Temptation, do not lead, please deliver us/When you a beast, you kinda cease to give a fuck.” Even when the musical bed is skeletal, the lyricism remains dense, stuffed with allusions. This moment of self‑mythologizing underscores how Cane & Able functions as both eulogy and affirmation; the MC reflects on his evolution from street‑corner cipher to cultural elder without softening his edge.

The record’s mid‑section widens the palette through unexpected collaborators. “Quiet Trip” features the Portland psych‑soul band Portugal. The Man and singer The Last Artful, Dodgr. It’s built on a gently pulsing bassline and warm keyboards; Thought tells stories of hustling in Philadelphia, dodging police raids, and hustling through extra‑legal means. The chorus contemplates the emptiness of digital life, lamenting how we derive self‑worth from social media interactions while walling ourselves off from meaningful human connection. On “Nature of the Beast,” the same guests return, this time for a more theatrical number with swirling strings and handclap rhythms. Thought croons in his lower register, then leaps into double‑time verses about conspiracy theories and algorithmic manipulation. Their presence broadens the sonic palette, bridging hip‑hop with psych‑rock and R&B. Some fans may balk at these detours—after all, the minimalistic boom‑bap of the earlier tracks anchors the record—but these songs act as breathing room, allowing the listener to process the lyrical density before diving back into battle.

“We Could Be Good (United)” finds Thought harmonizing with C.S. Armstrong and the women of OSHUN over Marvino Beats’ shimmering chords. The chorus pleads for unity and self‑love, while Thought’s verses namecheck artists from Marvin Gaye to Basquiat, positioning himself within a lineage of Black creativity. The song’s hopeful tone contrasts with the album’s heavier moments, offering a glimpse at the other side of anger: the desire to build something better. In “Steak Um,” he pairs with Schoolboy Q on a beat that feels like a black‑and‑white noir film; off‑kilter drums stutter around an eerie guitar lick. Q’s verse is delivered with his signature slurred urgency, but the star of the track is Thought’s self‑analysis: “Listen, they told me I was bound to lose, he raps. I had the crown to prove and fucked around and found the tools/Could have failed, but I was compelled, I torched the trails/Of an Orson Welles, rock jewels big as oyster shells.” The reference to Orson Welles equates filmic trailblazing with artistic independence, further illustrating Thought’s cross‑disciplinary mind. On these tracks, Sean C allows co‑producers Sal Dali and Marvino Beats to add flourishes—a guitar loop here, a vocal filter there—but their touches never distract from the MC; instead, they paint in texture around his voice.

The album’s thesis solidifies on “Thought vs Everybody.” A minimalist loop and dry snare give the feel of a cypher in an empty club. Thought darts through internal rhymes and extended metaphors, drawing parallels between ancient griots, modern street poets, and revolutionary leaders. He raps, “See the game is to keep us off balance/Like a gambler with a hidden ace and a bulletproof talent/They keep sending cowards to war, but never the war hawk/They give you secondhand information and wonder why you talk.” The track was the first single released in August 2020, and its video features protest imagery, but Thought has explained that it was recorded in early 2019; the themes of police brutality and political gaslighting came from intuition rather than reaction to current events. Without a chorus, the song feels like a gauntlet thrown to all challengers. As the track closes with a final knockout punch, one understands why the project bears the subtitle “Cane & Able”: it is a tool to capability.

The concluding stretch returns to heavy introspection. “Ghetto Boys and Girls (Fuel Interlude)” sets up “Fuel.” Here, Portugal. The Man and The Last Artful, Dodgr return alongside the band members to craft a soulful, gospel‑infused backdrop. Thought reflects on Black resilience, raising children amid danger, and finding spiritual nourishment in the struggle. The interlude’s loop of children shouting “fuel” bleeds into a proper song where he raps about burning bright despite systems designed to extinguish him. The final track, “I’m Not Crazy (Outro),” echoes the opener but flips the tone; what was once paranoia now sounds like defiant laughter. He peppers the outro with shout‑outs to mentors, family, and fallen comrades (including Malik B.), offering a eulogy and a benediction all at once.

Part of Cane & Able’s power lies in its balance of unfiltered aggression and musical nuance. Throughout the record, Sean C’s crisp drums and ominous piano loops provide the skeleton; LV’s co‑production lends subtle harmonic movement; Sal Dali and Marvino Beats add texture without ever crowding the MC. When Thought invites guests, they amplify the intensity—Pusha T and Killer Mike on “Good Morning,” Schoolboy Q on “Steak Um”—but the project remains his. Even detours with Portugal. The Man and The Last Artful, Dodgr serve his agenda; they widen the sonic spectrum without upstaging his delivery. The occasional sung hook or rock‑leaning bridge functions like a pivot in a jazz solo, allowing the rapper to re‑enter from a new angle.

Since the album was completed before Malik B.’s death, its themes acquire an unintentional poignancy. The three‑month delay meant that listeners heard it after experiencing a summer of pandemic isolation and police protests. Dedicating the project to his fallen bandmate, Thought channels grief into creative ferocity, making the record feel both cathartic and urgent. In Streams of Thought, Vol. 3: Cane & Able, he doesn’t attempt to escape the chaos; instead, he dives head‑first into it, weaving images of Mansa Musa, Icarus, and Orson Welles into laments about mass incarceration, digital alienation, and historical amnesia. His partnership with Sean C recalls early 1990s New York hip‑hop yet feels unmoored from any era. The result is an album that extends the series’ foundations without repetition. Volumes 1 and 2 showcased his technical brilliance; Vol. 3 frames that brilliance within a fully realized world, thick with mood and narrative. By the time the final piano loop fades, listeners have traversed state prisons and quiet trips, war‑torn mornings and nature’s beasts. Cane & Able stands as both a memorial and a manifesto: a reminder that in times of sorrow, art can still carve out a stream of thought with a razor’s edge.

I would like this twice if I could 💜