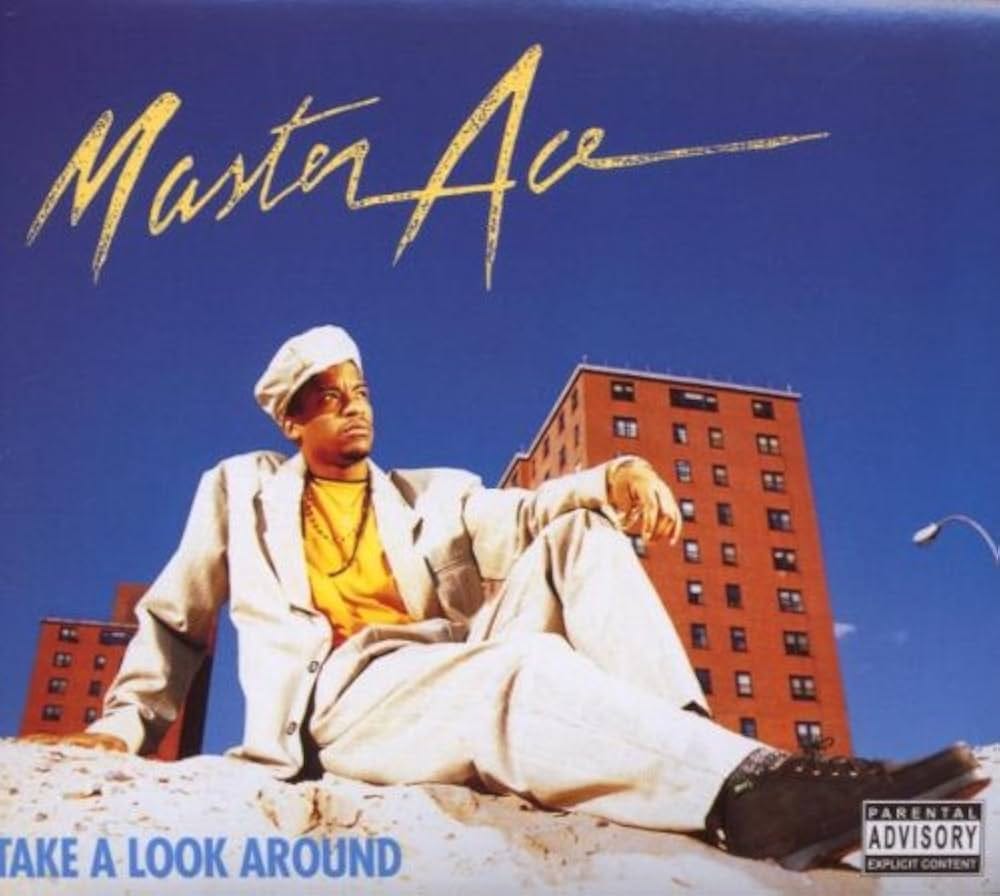

Anniversaries: Take a Look Around by Masta Ace

Take a Look Around moves between two moods: lighthearted battle rhymes and earnest commentary on ghetto life. Ace never wholly separates them; even his braggadocio carries a moral undertone.

When Duval Clear stepped to the mic in the late 1980s, he wasn’t the most flamboyant member of the Juice Crew, but he did have something others lacked: a degree in marketing and a scholar’s sense of balance. The Brooklyn rapper who became Masta Ace had graduated from the University of Rhode Island in 1988 and returned home with six hours of studio time he’d won at a campus rap contest. That prize brought him to producer Marley Marl’s House of Hits studio in Long Island. Marley heard a poised voice that could convey a concept and offered the young MC a spot on 1988’s “The Symphony,” the posse cut that introduced him to new fans and later led to a solo contract.

Ace’s debut album, Take a Look Around, appeared on Cold Chillin’/Reprise on July 22, 1990. In a crowded era of early‑’90s rap releases—the same year saw Public Enemy’s Fear of a Black Planet and A Tribe Called Quest’s People’s Instinctive Travels—Ace’s record didn’t reach blockbuster status. Yet its thirteen tracks offered an education in understated storytelling and sample‑driven funk. The LP remains one of the few Juice Crew albums where the quietest MC took center stage.

Take a Look Around has the cohesive feel of a small team at work. Marley Marl produced most tracks using his SP‑1200 drum machine and an ear for funk breaks, assisted by Mister Cee, the DJ best known for his affiliation with Big Daddy Kane. Ace also received co‑producer credit on every song; he later explained that many of the source records used as samples came from his mother’s and uncle’s collections. For example, the loop on the opening song “Music Man” was pulled from Grand Funk Railroad’s “Nothing Is the Same.” Ace told Wax Poetics that he kept rewinding the record for hours until Marley woke up, lifted the loop, and recorded Ace’s off‑the‑cuff rhymes, a rare instance in his career where he didn’t write out his verse. That spontaneous energy sets the tone for a record that feels like a jam session guided by a professor.

The House of Hits sound is recognizable: dusty drum breaks, rolled hi‑hats, and sharp snare pops. Rock & Roll Globe’s 30th‑anniversary essay notes that Marl relied on three‑quarter drum breaks, glissando samples, and James Brown grunts while flirting with synthesizer experiments. “Four Minus Three” rides a clipped guitar riff from Little Royal & the Swingmasters’ “Razor Blade.” “Brooklyn Battles,” built over Eddie Kendricks’ “If You Let Me,” layers descending bass with horns, while Ace warns listeners about street conflicts. Mister Cee, whose production appears on two tracks, gravitates toward deeper bass. His beat for “I Got Ta” borrows James Brown’s phrase “I got ta” from “Talkin’ Loud and Sayin’ Nothing” and slows it to a contemplative pace. The overall feel is funkier than other Cold Chillin’ releases; there are no dance‑floor club cuts, just patient grooves designed for headphones and home stereos.

Whereas Big Daddy Kane’s records flaunted lush strings and horns, Ace favored stripped‑down arrangements. On “Letter to the Better (Remix)” he raps over a taut loop of The O’Jays’ “Give the People What They Want,” admonishing fellow MCs to move beyond empty boasting. “Can’t Stop the Bumrush” features a bassline cut from Joe Cuba’s “Bang Bang”; Ace rides the beat with quick internal rhymes, mocking inferior rappers (“Stop slippin’, you’re the klutz of the year”). These tracks put his voice front and center: you notice his cadence more than any studio gimmicks.

In the late 1980s, the Juice Crew housed some of hip‑hop’s most outsized personalities. Big Daddy Kane delivered verses like an R&B crooner crossed with a street hustler; his lyrical bravado and love‑god persona made him the Crew’s breakout star. Masta Ace occupied the opposite end of the spectrum. According to Rock & Roll Globe, he was the crew’s “secret weapon”—a soft‑spoken, college‑educated idealist. Mister Cee, who deejayed for Kane, said he liked Ace precisely because he was the opposite of the flamboyant lyricist. Ace’s academic background sharpened his writing; he thought critically about narratives instead of simply stacking metaphors. This “collegiate smart” delivery gives his rhymes a measured quality. Even when he boasts, as on “Can’t Stop the Bumrush,” he does so with a wink—his flow remains laid back, and he rarely raises his voice. The contrast is apparent when he shares space with Kane on “The Symphony,” where Ace opens the posse cut with a composed verse that stands out for clarity rather than swagger.

Ace’s voice is also different in timbre. Kane’s baritone commanded attention, but his lighter tone allowed him to slip into characters. On “Me and the Biz,” the album’s most playful cut, he impersonates Biz Markie after the real Biz declined to record his own verse. In interviews, Ace recalled that Marley had saved the beat for Biz. When Biz refused to record at House of Hits, Ace wrote and recorded a full duet, then imitated Biz’s distinctive lisp and off‑key singing; Marley found the impersonation hilarious and kept it. Ace later regretted that Warner Bros. selected the song as the lead single because he considered it a gimmick, but the track reveals his sense of humor and his ability to mimic friends while still delivering his own bars. When his voice changes into Biz’s, you can hear his ease at code‑switching, a trait of someone who studied language as much as he enjoyed wordplay.

On “Music Man,” Ace introduces himself as a traveling performer who uses music to uplift communities. He flips the phrase “music man” into a superhero motif, promising to rescue neighborhoods with rhyme. “Can’t Stop the Bumrush” is all swagger; Ace warns would‑be challengers that once he starts performing, the impact is “thorough” and tells a competitor, “You’re a featherweight and I’m a million miles beyond.” The song is structured like a cipher: each verse ends with a call‑and‑response for the DJ to cut the beat. In “Me and the Biz,” he and his imaginary partner trade comedic verses about performing shows and paying bills; his Biz impersonation underscores the camaraderie among Juice Crew members.

Even the party songs contain lessons. “Postin’ High” plays like a cautionary tale about a wild night out. Over a slinky bassline, Ace narrates his trip to a club filled with “freaks,” weed smoke and big talkers. At the end, his friend Mister Cee reminds him that though they had fun, they need to stay focused on their careers and not let the fast life derail them. The message is subtle: enjoy yourself, but remain grounded.

In “I Got Ta,” Ace lays out responsibilities he feels as an educated rapper from Brownsville: “I got ta teach the youth that they’re capable / I got ta show the ghetto is escapable.” He acknowledges obligations to inform listeners about the possibilities beyond their surroundings. He also alludes to learning about white people’s world, suggesting a desire to bridge communities. The hook uses a sample of James Brown shouting “I got to,” turning Brown’s emphasis into a mantra for social change.

“The Other Side of Town” is the album’s heart. The track begins with a homeless man begging for spare change. Ace then raps in first person as a young boy trapped in poverty: “The life of a poor man, consider me desperate/I’m starvin’ for a meal and I’m tryin’ not to steal.” He describes his teacher ignoring his hunger in class and feeling ashamed when his clothes are tattered. In the third verse, he contemplates crime as the only route to feed his mother: “If I took a pull of a gun, would you call me a fiend?” The song doesn’t moralize; it simply illustrates the pressures that push a youth toward illegal means. The sorrow in Ace’s delivery conveys empathy rather than condemnation, and the beat is sparse, so listeners focus on the narrative.

Ace continues his social commentary in “As I Reminisce,” telling vignettes about teenage pregnancy and the perils of hustling. The final track, “Together,” ends the album with a plea for unity. He raps, “A friend is a friend till the end if he’s sincere / A friend won’t lend if he’s lending you his ear,” and encourages people to support one another. Rock & Roll Globe noted that Ace’s positivity distinguishes the record; he consoles a hungry classmate rather than scolds him, and he asks Brooklynites to help each other. There is a moral thread connecting each song: the brags are balanced by caution, and the caution is humanized by self‑deprecation.

Today, Take a Look Around occupies a revered yet understated place in hip‑hop’s golden age. While albums like Nas’s Illmatic or Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back are often cited as the era’s essential texts, Ace’s debut quietly influenced a generation of lyricists. The record captures the transition from the late ’80s drum machine era to the jazz‑infused production that would define the early ‘90s: Marley and Mister Cee’s beats foreshadow the smoother textures of Pete Rock & C.L. Smooth and the storytelling depth of Nas.

Ace’s narrative style paved the way for MCs who combined braggadocio with introspection. Eminem, who has repeatedly cited Ace as an influence, has credited him for showing how to weave humor into dark tales. Anderson .Paak and Kendrick Lamar have referenced songs like “The Other Side of Town” when discussing early rap storytelling. Ace’s later projects, especially the concept album Disposable Arts (2001), show how he continued to build on the structure and themes first explored on his debut.

The album also remains a time capsule of pre‑gentrification Brooklyn. “Brooklyn Battles” paints Brownsville as a place of both danger and pride. Ace warns outsiders to respect the borough: “If you’re new in town, don’t like the sight of blood/You’ll be out of luck, stuck, because these kids are rough.” Yet he also celebrates the resilience of its residents, rapping about basketball games, block parties, and the strength of his community. “Together” extends that pride outward, urging listeners from all neighborhoods to unify. In today’s climate of displacement and nostalgia, these songs resonate as documentation of a vanished era.

If there is a criticism to be made, it is that the record sometimes lingers in cautionary messaging. Ace later admitted that some verses came off as preachy. Yet that earnestness can be refreshing in a landscape where nihilism often masquerades as authenticity. Ace speaks to his younger self as much as his audience. When he raps, “I got ta stay in touch with my inner scene,” he’s reminding himself to maintain balance between school and street, humor and responsibility, beat and lyric. That internal dialogue gives the album depth. The album invites fans of classic rap to revisit early ‘90s New York not through the lens of nostalgia alone, but through the eyes of an MC who balanced a marketing degree with a love for the art. For those willing to listen closely, the record still speaks.