Anniversaries: Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey by The Foreign Exchange

Released during a period when mainstream R&B leaned toward trap drums and introspective alternative R&B, Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey is a deliberate throwback and forward‑looking experiment.

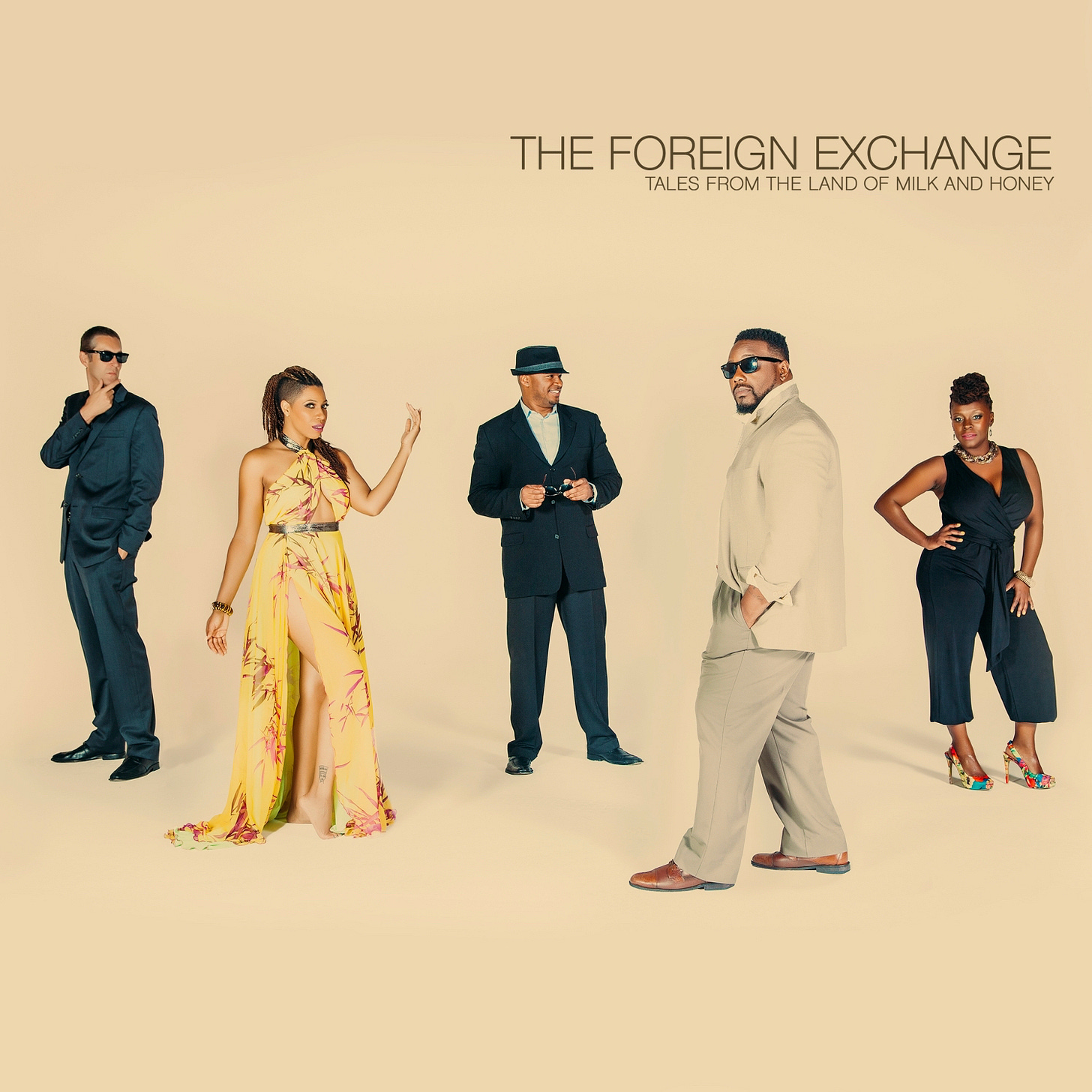

The Foreign Exchange began as an improbable trans‑Atlantic correspondence. In the early 2000s, Dutch producer Nicolay and North Carolina rapper Phonte Coleman met on Okayplayer’s message board, mailed beats and vocals across the ocean, and, before they met in person, forged a debut full of rich R&B‐tinged hip‑hop. Over the subsequent decade, the duo evolved. Hip‑hop receded as Phonte explored soul singing; Nicolay dove into world‑music textures and live instrumentation. By the time Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey arrived ten years ago today (and their latest release as of this writing), the group’s lineup resembled a small collective: keyboardist‑producer Zo! co‑produced every track, singers Carmen Rodgers and Tamisha Waden shared co‑lead and background duties, and the studio became a lively, collaborative space rather than an exchange of files. Their fifth full‑length is a lean, 37‑minute set; its breezy ten songs distill funk, Brazilian rhythms, Chicago house, and boogie into a suite that radiates humor, romance, and maturity.

Previous Foreign Exchange albums were primarily built on Nicolay’s compositions and Phonte’s lead vocals, with guest spots from female singers. 2013’s Love in Flying Colors hinted at a broader ensemble by featuring Zo!, Rodgers, and Waden, but they were still “supporting cast.” Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey pushes them to the foreground. In an interview with Indy Week, the group acknowledged that Zo! co-produced the entire album alongside Nicolay, an unprecedented step that split the sound down the middle. Zo!’s keyboard work and chord voicings flesh out grooves that once would have leaned heavily on Nicolay’s synth orchestrations, giving the songs a looser, warmer feel. Carmen Rodgers and Tamisha Waden are “proper pieces of The Foreign Exchange.” Rather than appearing on one or two tracks, they weave throughout the record, sometimes leading, stacking harmonies behind Phonte. Their voices bring textures the group had not fully embraced before: Rodgers’ airy soprano evokes Patrice Rushen and Deniece Williams; Waden’s church‑trained alto adds gospel grit.

Zo! has described the sessions as marathon creative bursts. On his “Studio Campfire Stories” blog, he recounts that he and Nicolay convened in Wilmington, NC, for multi‑day sessions. While they had previously traded ProTools files from separate studios, this time they worked together. During one trip, they unexpectedly wrote what would become the ballad “Face in the Reflection” by “playing around” on a Yamaha Motif; Nicolay captured Zo!’s improvisation and built drums around it. Another marathon produced the house track “Asking for a Friend.” When the pair set up on March 31, 2015, they decided to create a four‑on‑the‑floor rhythm, though Zo! had “never even played on one.” Nicolay built the drum pattern piece by piece, and Zo! layered Rhodes chords, Moog bass, and strings; the resulting instrumental felt like an old‑school house party.

Phonte and Carmen recorded vocals simultaneously in Raleigh while Nicolay and Zo! were creating tracks in Wilmington. After hearing the music, Phonte initially thought the house groove might be too hard for the album, but quickly changed his mind and emailed the producers with the subject line “Asking for a Friend.” In Zo!’s retelling, Phonte wrote that “this shit went from ‘maybe it’s too hard’ to ‘this could be the first single’ real quick.” That moment signaled that the project was no longer just a Nicolay & Zo! EP; with Rodgers, Waden, cellist Shana Tucker, and former touring vocalist Carlitta Durand in the mix, the crew decided to make a full-fledged Foreign Exchange album.

The album opens and closes with warm, sun‑kissed instrumentals that hint at both tropical landscapes and interior comfort. The title track “Milk and Honey” uses a syncopated samba groove reminiscent of Brazilian jazz group Azymuth and the sophisticated pop of Sérgio Mendes. A gentle acoustic guitar and tambourine shuffle under Waden’s wordless vocalizations, while flutes and synth pads flutter above; the track evokes an open courtyard at dusk. Nicolay’s affinity for international rhythms stems from his City Lights solo series, particularly City Lights Vol. 3: Soweto, whose South African dance drums seep into these grooves. The record closes with “Until the Dawn (Milk and Honey Pt. 2),” revisiting the opener’s chords but slowing the tempo and adding a buoyant bassline. Waden, Rodgers, and Phonte share the vocals, repeating “we’ve come this far, we might as well keep going.” Like Stevie Wonder’s “As,” the song blurs spiritual and sensual gratitude; the band treats the groove as a prayer and a dance invitation. Zo! and Nicolay anchor the track with glistening Fender Rhodes and gentle congas.

The album’s lead single, “Asking for a Friend,” is a departure and a thesis. Where previous Foreign Exchange dance tracks flirted with house rhythms—2013’s “So What If It Is” and Nicolay’s remixes—this song fully embraces Chicago house. Nicolay constructs a pounding four‑on‑the‑floor with open hi‑hats, tom fills, and claps; Zo! adds a bubbling Moog bass and sparkling chords. Phonte enters speaking in a faux British accent—a self‑conscious butler persona reminiscent of Rick James’ campy interludes and Marvin Gaye’s “Ego Trippin’ Out.” He recites, “Work work work, we’ve got bills to pay,” with the detached cadence of Geoffrey from The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.

Musically, “Asking for a Friend” signals a shift in the group’s house flirtations. Previous single “So What If It Is” rode an Afro‑house beat but kept the vocals laid‑back; here, the intensity of the four‑beat pulse propels Waden to power‑sing, and the chord changes recall early Nuyorican Soul records. Zo!’s instrumental outro extends the party with synth vamps and hand‑claps, letting dancers revel. The track italicizes the collaborative interplay, where a line composed in one studio inspires a bass riff in another, and then a character voice from Phonte triggers a melodic flourish from Waden.

Following the Brazilian opener and the house single, “Work It to the Top” dives into ‘80s boogie. Nicolay and Zo! craft a bassline that struts like Cameo’s “Candy,” layering slap bass, plinky synth stabs, and clattering percussion. Phonte adopts a nasal croon reminiscent of funk singer Steve Arrington by singing about ambition and hustle with campy flair: “Gotta get it, gotta give it all I got.” The rhythm section stops and starts, creating call‑and‑response pockets that Rodgers and Waden fill with stacked harmonies. Phonte’s lyrics also recall Ready for the World and other mid‑’80s funk groups with playful innuendo and corporate satire: he sings of climbing corporate ladders while hitting falsetto squeals. By invoking these influences, the Foreign Exchange celebrate Black club culture without succumbing to nostalgia. Zo!’s synth chords lean into gospel cadences, and the song modulates upward in the final minute, offering a satisfying release.

At the album’s center are two mid‑tempo numbers that anchor its adult‑contemporary soul. “Body” is a warm, sensual song about staying in with a partner rather than going to the club. Over a sleek, four‑on‑the‑floor beat and muted Rhodes chords, Phonte croons: “I don’t want to go out to no club tonight, I just want your body.” The groove draws from Chicago house but strips out the grit, leaving a plush pillow of chords and hi‑hat shuffles. When Waden enters on the bridge with wordless melisma, the track becomes a duet of contentment—two lovers basking in domestic warmth rather than chasing external thrills. This theme echoes Phonte’s 2011 solo album Charity Starts at Home, where he rapped about choosing family over nightlife; here he sings it as a matured adult.

“Truce” shifts the tempo down further. Framed by acoustic guitar and gentle hand percussion, the song presents conflict resolution as a two‑way street. Phonte’s verse acknowledges past arguments; Waden’s chorus, “Lay down your weapon, let’s just call it a truce,” reassesses love as negotiation. The arrangement touches Stevie Wonder territory with its chromatic keyboard runs and harmonica‑like synth leads. At the song’s midpoint, Rodgers enters with a vulnerability that feels like she’s stepping into a conversation mid‑argument: “Beside me, you guide me, you wipe away my tears/So why won’t you, why don’t you, say you won’t disappear?” Her plea underscores the album’s overarching theme: long‑term relationships require mutual effort.

The mini‑instrumental “Sevenths and Ninths” functions like a palette cleanser. At only 1 minute 40 seconds, it’s essentially a chord study: Zo! and Nicolay build a lush progression around extended jazz voicings while a string section coos. Phonte remains silent, letting listeners float. The track’s title points to the extended intervals used in jazz chords; musically, it nods to Donny Hathaway’s arrangement style. The piece foreshadows the introspection of the album’s emotional centerpiece, “Face in the Reflection.” When Phonte received the instrumental, he delivered one of his most introspective hooks: “Do you ever wonder why/You can never unify/The person that you are with the person that you think you should be?/When you look into the mirror, try/To keep it strong and not to cry/When you don’t feel the connection to the face in the reflection you see.” Waden and Rodgers harmonize softly, echoing Phonte’s lines as if they’re voices in his head.

“As Fast as You Can” is a disco‑blasted romp that finds Phonte racing to a lover. The groove is reminiscent of Donna Summer’s Giorgio Moroder productions, but the production isn’t derivative. Instead, the track uses live‑sounding drums and funky bass, giving the rhythm a human ebb. Rodgers handles the second verse, her airy tone drifting above the beat, while Waden’s harmonies cushion each phrase. “Disappear” slows the tempo but maintains a slick, cosmopolitan vibe. It features Carmen Rodgers on lead, singing about a partner’s tendency to ghost and her desire for commitment: “Why won’t you, why don’t you, say you won’t disappear?” Nicolay’s production mixes bossa nova guitar with glossy synths; subtle percussion gives the track a yacht‑soul sheen. Zo!’s electric piano fills the space between Rodgers’ lines, while Waden’s background vocals swirl like wind.

Released during a period when mainstream R&B leaned toward trap drums and introspective alternative R&B, Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey stood as a deliberate throwback and forward‑looking experiment. The album toggles between past and present, referencing the Pointer Sisters and Cameo on up‑tempo tracks and neo‑soul balladry on slower numbers. It appeals to listeners who grew up on Jimmy Jam & Terry Lewis and Stevie Wonder but are open to house music and bossa nova. It captures a band comfortable enough to poke fun at itself and serious enough to dive into introspection. In the broader R&B landscape, Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey sits alongside works like Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly and D’Angelo’s Black Messiah as part of a mid‑2010s renaissance of Black artists synthesizing past traditions with contemporary sounds. But where those records emphasize political commentary and weighty spirituality, Tales chooses joy. Its collaborators swap verses like friends at a cookout; its grooves recall block parties; its ballads invite quiet reflection without gloom.

The Foreign Exchange may have started as an unlikely file exchange between a rapper and a Dutch producer, but on Tales from the Land of Milk and Honey, they cultivated a collaborative paradise—a place where house beats, bossa nova, boogie funk and soul ballads coexist, where female voices are central and where adults are free to dance.