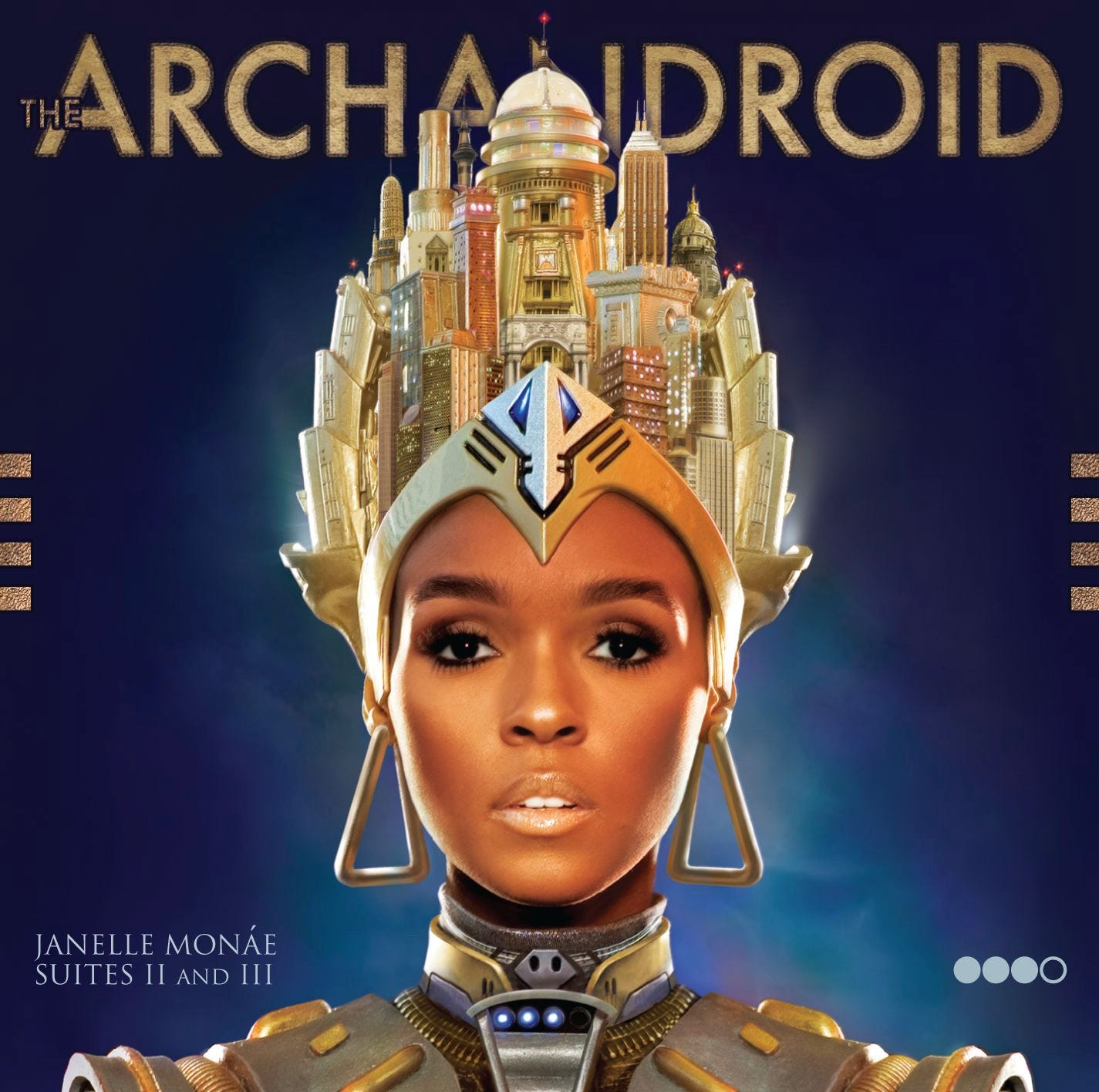

Anniversaries: The ArchAndroid by Janelle Monáe

The ArchAndroid remains a reminder that the album, sequenced with cinematic care and armed with a fiercely coherent worldview, can still feel like the most radical unit of musical expression.

As clear as day, Janelle Monáe’s debut still feels refreshingly audacious fifteen years on, a roaring, genre-warping dispatch that expands the Afrofuturist cityscape she sketched on 2007’s Metropolis: The Chase Suite into something approaching a full-length “emotion picture,” the preferred descriptor. Where the EP introduced android outlaw Cindi Mayweather and the classist future metropolis hunting them for daring to love a human, the LP thrusts that narrative into widescreen, scoring it with chamber strings, Dresden-style cabaret, grease-fire funk, and space-folk lullabies in 68 kaleidoscopic minutes. Few debut albums have mapped so many musical coordinates while preserving such a cohesive arc; fewer still have done so while sustaining a liberation myth that doubles as a meditation on Black femme agency in oppressive systems.

Few debut albums have mapped so many musical coordinates while preserving such a cohesive arc; fewer still have done so while sustaining a liberation myth that doubles as a meditation on Black femme agency in oppressive systems. We find Cindi on the run, drafted by time-hopping freedom fighters to become the “mediator between the haves and the have-nots,” their android circuitry symbolizing historically marginalized bodies. The filmic overtures that bookend each suite recall golden-age orchestral soundtracks, cueing listeners to experience the record cinematically while stitching movements together with leitmotifs of propulsive strings and muted brass. Monáe explained to NPR that this was “an album that arrived in dreams,” complete with staging instructions, so the overture format served both as plot exposition and palate cleanser for the stylistic swerves to come.

Those swerves erupt immediately. “Dance or Die,” Cindi’s encrypted dispatch from the underground, recruits poet Saul Williams over Afro-Latin percussion and skittering horn riffs, jump-cutting into the ska-inflected “Faster” before sliding into the velveteen disco-soul of “Locked Inside,” whose rhythm section winks at Michael Jackson’s “Rock With You.” Across the record, Monáe, Chuck Lightning, and Nate “Rocket” Wonder smuggle their film-score obsessions—Goldfinger strings, Morricone guitar twang—into 21st-century R&B frameworks, an approach Monáe once likened to “Prince sitting in with Debussy while OutKast hijacks the mixing board.” That ethos crests mid-Suite II with “Tightrope,” a brass-drunk funk stomp featuring Big Boi that admonishes resistance fighters to stay balanced on the line between fear and hubris; the single’s kinetic Fred Astaire-on-wheels video became an early statement of the tuxedo-and-pompadour iconography and was later canonized in year-end lists. “Cold War,” released a few months after, distilled the album’s existential stakes into two and a half minutes of serrated new wave, its single-take video capturing Monáe’s face as it flickers from resolve to panic to tears, a reminder that the android mythos is merely a mirror for human vulnerability.

Sequencing is where The ArchAndroid quietly flexes its meticulous architecture. Each suite opens with an overture that quotes melodic fragments yet to appear, then unspools like a thematic spiral: hope, flight, betrayal, resurrection. Suite II builds euphoria through escalating BPMs until “Sir Greendown,” a 50s doo-wop reverie in which Cindi imagines the forbidden romance finally within reach; the suite closes by crashing that dream against the insurgent rave-punk of “Come Alive (The War of the Roses).” Suite III reverses the pattern, beginning in pastoral psychedelia (“Mushrooms & Roses”), then accelerating toward the four-on-the-floor utopianism of “Wondaland,” pausing for the Simon-and-Garfunkel-tinged folk hymn “57821,” and, after the Debussy-sampling “Say You’ll Go,” ending not with bombast but with “BaBopByeYa,” a nine-minute Afro-Cuban big-band opera that stages Cindi’s martyrdom and cosmic rebirth. Because these cycles of propulsion and release mirror both a hero’s journey and the tension-and-release mechanics of classic LP sequencing, attentive listeners experience the story subconsciously even if they ignore the libretto.

Threaded through the genre shifts is an Afrofuturist grammar of liberation. Academic readings have noted how Monáe queers time by projecting antebellum hierarchies into a dystopian future, allowing the android to dramatize the ongoing policing of Black and queer bodies while refusing the passive victim role that older sci-fi androids often occupied. Cindi’s defiance draws on spiritual-gospel call-and-response (“BaBopByeYa”) and black-radical invocations (“Running fast through time like Tubman and John Henry,” she sings on “Neon Valley Street”) so that the album’s speculative conceit remains tethered to real histories of resistance. The Quietus pointed out that the project’s promiscuous genre-mixing itself enacts border erasure, refusing to let Black pop be fenced into R&B or funk and instead asserting ownership over symphonic rock, folk, and cabaret.

Upon release, the LP entered the U.S. Billboard 200 at a modest No. 17 with 21,000 first-week sales—hardly blockbuster numbers—but its influence quickly outpaced its chart position. The Guardian crowned it the best album of 2010, praising its sense of “communal possibility,” while NPR framed it as a template for expansive pop storytelling. Pitchfork later slotted it at 116 in its 200 best albums of the 2010s, Crack Magazine placed it in the decade’s top 100, and its orchestrated Afrofuturism can be heard echoing through subsequent works by Beyoncé (Lemonade), Solange (A Seat at the Table), and FKA twigs (LP1), all of whom adopted narrative multi-disciplinarity as standard practice. Within Monáe’s own catalog, the record’s insistence on emotional-political synthesis set the stage for The Electric Ladyand Dirty Computer, albums that push the saga forward while grounding it ever more explicitly in present-day fights for queer and racial justice.

Today, The ArchAndroid functions simultaneously as origin story, manifesto, and roadmap. It shows how an artist can braid speculative fiction and soul choreography into an elastic framework resilient enough to absorb Baroque string quartets, Hendrix fuzz solos, and Parliament bass throb without losing narrative coherence. It also proves that concept albums need not trade emotional punch for intellectual scaffolding; every anthemic chorus—“tip on the tightrope,” “I was made to believe there’s something wrong with me”—carries the same weight as any plot twist in Cindi’s saga. By picking up exactly where Metropolis left off and then detonating the boundaries of what a suite-based pop epic could sound like, Monáe ensured that the android’s flight would echo long after the closing horns fade, urging each new listener to imagine their own break from the gravitational pull of oppression. In an era when pop careers often pivot on streaming-friendly singles, The ArchAndroid remains a reminder that the album, sequenced with cinematic care and armed with a fiercely coherent worldview, can still feel like the most radical unit of musical expression.

This album is a favorite for sure, and the 33 and 1/3 did it justice. I keep hoping she’ll fill that last dot with another album or EP. I love how the story unfolds because it feels luxurious.