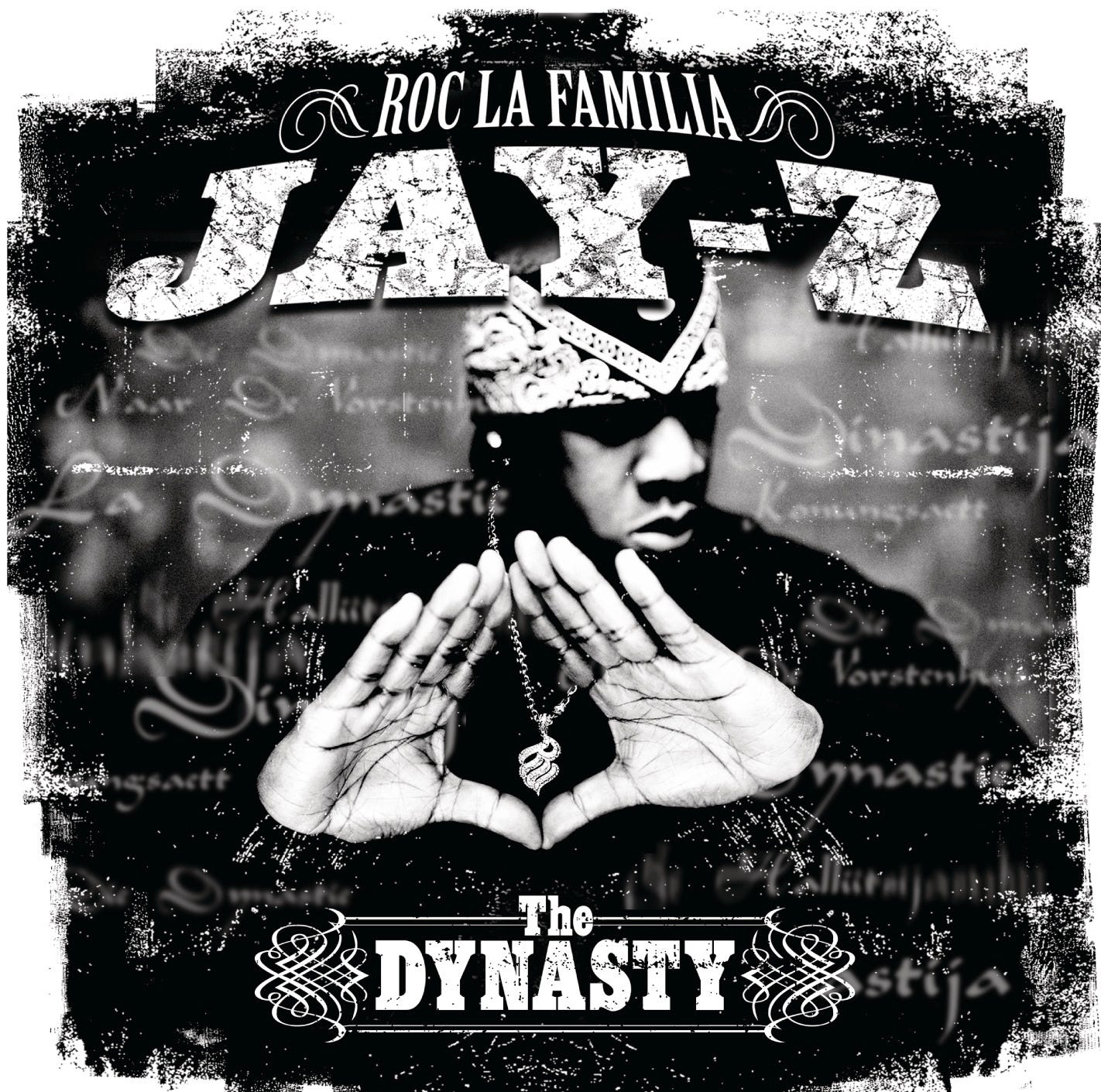

Anniversaries: The Dynasty: Roc La Familia by JAY-Z

JAY‑Z was transitioning from rapper to executive, and Roc‑A‑Fella was morphing from a boutique label into an empire. The Dynasty offers a snapshot of early‑21st‑century Black music culture.

The turn of the century found Shawn “JAY‑Z” Carter looking down from a commercial summit. 1998’s Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life and 1999’s Vol. 3… Life and Times of S. Carter had moved five and three million copies, respectively. Def Jam’s legendary 1999 Hard Knock Life Tour was named after his hit single; by the fall of 2000, he was as much a mogul-in-training as a rapper. Yet Carter’s ambitions reached beyond his own chart positions. Roc‑A‑Fella Records, the label he co‑founded with Damon Dash and Kareem “Biggs” Burke, had amassed a roster of hungry MCs from New York and Philadelphia. Rather than wait for each artist to find an audience, JAY‑Z decided to leverage his stardom to introduce the world to his crew. The resulting project, The Dynasty: Roc La Familia, was initially conceived as a compilation showcase; Dame Dash later recalled that the plan was to make a full‑crew record but stamp JAY‑Z’s name on the cover to attract more fans. Def Jam opposed releasing it as a group album because the label feared it would get lost in stores, so the compromise was to market it as JAY‑Z’s fifth solo outing while giving Roc‑A‑Fella’s signees room to shine.

Carter’s previous albums drew heavily on superstar producers like Timbaland, Swizz Beatz, and DJ Premier. For The Dynasty, he pivoted toward lesser‑known beatmakers, then swirling around Baseline Studios. During late‑July sessions in 2000, Memphis Bleek’s engineer called out sick; Young Guru filled in and invited young producers Just Blaze and Kanye West to the studio. Bink! was working in the smaller room, and his beat—built on a pitched‑up sample from the Moments’ “What’s Your Name”—became “You, Me, Him and Her,” the first track recorded for the project. These sessions marked the arrival of a new sonic axis. Instead of chasing the keyboard‑driven bounce of Swizz Beatz or the futuristic thump of Timbaland, Carter embraced a patchwork of soul samples, funk riffs, and West Coast synths. The Dynasty introduced “newcomer producers the Neptunes, Just Blaze, Kanye West, and Bink!”, and Roc‑A‑Fella’s own history page adds that Carter deliberately avoided returning to Timbaland or Swizz, choosing instead to “select beats from a new crop of producers… each beat‑smith would go on to become consistently involved in future Roc‑A‑Fella projects.”

Just Blaze—then a 22‑year‑old New Jersey native—announced himself with the album’s opening “Intro,” flipping a slice of Kleeer’s “She Said She Loves Me” into regal brass and soaring strings. His “towering sample” set an immediate tone for the project and has been called one of hip‑hop’s best intros. The song isn’t simply an instrumental flourish; JAY‑Z uses it to set a cinematic scene, name‑checking the Ennis Cosby murder case and reflecting on how mainstream media still viewed him as a drug dealer despite his success. It’s a miniature autobiography rolled into ninety seconds—a tone poem for an album that toggles between street reportage and champagne‑soaked bravado.

Rick Rock, known for crafting Bay Area anthems, brought a different energy. His tinny synthesizer stabs and military drums fuel the riotous “Change the Game” and the flashy “Parking Lot Pimpin’,” the latter built around a two‑note guitar riff and whistles that conjure low‑rider hydraulics. These songs, tailor‑made for radio rotation, show Carter still courting mainstream clubs while giving Beanie Sigel and Memphis Bleek their own spotlight. Rick Rock also produced “Get Your Mind Right Mami,” a pimping anthem featuring Snoop Dogg and R&B singer Rell. Over a languid bassline, JAY‑Z plays the debonair hustler giving a woman a makeover: “Relax yourself, let your conscience be free/You now rollin’ with them thugs from the R‑O‑C… It’s a secret society, all we ask is trust/And within a week, watch your arm freeze up.” The lines feel both like recruitment into a crew and a seductive sales pitch; Snoop’s verse later flips the tone into West Coast pimpology.

Bink!, steeped in gospel and soul records, contributes two of the album’s most vibrant posse cuts. “You, Me, Him and Her” loops the sped‑up chipmunked Moments sample into a swirling backdrop for JAY‑Z, Beanie Sigel, Memphis Bleek, and the underrated Amil to trade verses. The song shouts out dynasty membership like a roll call, each rapper staking their claim to the “secret society.” Bink! also helms “1‑900‑Hustler,” a conceptual skit‑song structured as a hotline for would‑be drug dealers. On the track, a hustler calls the Roc’s hotline asking for advice; JAY‑Z answers with instructions for setting up shop (“Say, ‘Hey, I’m new in town, I don’t know my way around/But I got some soft white that’s sure to come back brown’”). Memphis Bleek coaches a young artist with street etiquette (“The strong move quiet, the weak start riots”), and newcomer Freeway tears through the beat with an urgent verse, his voice rising in pitch to match the horns. Freeway wasn’t officially signed when the album was recorded; he wasn’t on Roc‑A‑Fella’s roster, and Jigglypuff even tried to recruit him before he officially inked with Jay’s label. Freeway’s appearance on “1‑900‑Hustler” gave him his break and led to his signing.

The most significant debut, however, belongs to Kanye West. He provides only one beat on The Dynasty, but “This Can’t Be Life” foreshadows his soul‑chopping aesthetic. Built around Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes’ “I Miss You,” his production is somber and reflective, coaxing vulnerability from the MCs. Beanie Sigel laments numbing his pain with drugs (“I’m tired of trying to hide my pain behind the syrups and pills”), JAY‑Z confesses fears of becoming a failure despite his success, and Scarface rewrites his verse after receiving news that a friend’s baby died in a fire. This track was one of Kanye’s breakout moments and remains his only placement on the album. The somber mood proves that the Roc crew could pivot from party records to introspective storytelling without losing cohesion.

Pharrell Williams and Chad Hugo, collectively the Neptunes, contribute just one song but deliver the album’s best‑known hit. “I Just Wanna Love U (Give It 2 Me)” strips away street pretense for pure hedonistic pleasure. Pharrell’s falsetto hook and bubbly synths create a playful framework for JAY‑Z to let his guard down and brag about champagne and luxury cars. This track is described as a “funky, upbeat” Neptunes track that captures early-2000s club energy. The beat’s infectious groove even inspired Britney Spears to reach out to the production duo, helping them break into the pop market. The song is all winks and asides: Jay instructs listeners to “Give me that funk, that sweet, that nasty, that gushy stuff,” reveling in double‑entendre while Pharrell’s hook glides overhead. The track’s enduring popularity illustrates that The Dynasty’s experiments weren’t limited to gritty street tales—it could also conjure mainstream hits.

After the triumphant “Intro” and club‑ready “I Just Wanna Love U,” the album toggles between posse tracks and solo showcases. “Change the Game” pairs JAY‑Z with Memphis Bleek and Beanie Sigel over Rick Rock’s whistle‑driven beat. Static Major’s late‑addition hook gives it a catchy refrain; the song lacked a hook for most of the recording process until Static delivered one at the last minute. While the MCs trade verses with practiced chemistry, the song’s repetitive production can feel like filler compared to the album’s richer arrangements. The same is true of “Parking Lot Pimpin’,” whose minimalist guitar riff and Lil’ Mo chorus provide a backdrop for unmemorable boasts. Even JAY‑Z’s solo “Squeeze 1st” relies on a standard Rick Rock loop and functionary rhymes about power and paranoia.

Just Blaze’s contributions provide the album’s heartbeat. On “Streets Is Talking,” he flips a soul sample into swirling horns while Jay and Beanie discuss loyalty and betrayal. Beanie raps, “The streets is not only watchin’ but they talkin’ now/Shit, they got me circlin’ the block before I’m parkin’ now,” capturing the paranoia of a hustler whose moves are scrutinized by rivals and police. JAY‑Z echoes the sentiment with lines about surveillance and snitching. The dynamic interplay between the two rappers—and Blaze’s cinematic production—foreshadows the chemistry that would define State Property records. “Stick 2 the Script” continues the partnership, but Sigel’s misogynistic lines (“I make bitches into stars…”) age poorly, reminding listeners that early‑2000s rap often trafficked in problematic bravado.

“You, Me, Him and Her” stands out as a pure crew anthem. Each member stakes a different claim: JAY‑Z boasts about wealth and exclusivity (“Ain’t no place on the planet that you’d rather be… It’s a secret society, all we ask is trust”), Memphis Bleek relishes his new mentor role, Amil delivers a raspy verse about loyalty and luxury, and Beanie injects humor. The interplay evokes a mixtape cypher more than an official album track, and the unpolished energy is part of its charm.

“Guilty Until Proven Innocent,” the only outside feature, pairs JAY‑Z with the Pissy Man over Rockwilder’s piss por production. Recorded amid Carter’s legal troubles stemming from a 1999 stabbing, the song flips the justice system’s mantra, with JAY‑Z asserting his innocence while referencing media judgment. It’s one of the album’s more radio‑friendly songs, though its presence feels odd among the crew‑centric cuts; Pissy’s hook, with his own later controversies, now casts a shadow. “Soon You’ll Understand,” a Just Blaze solo showcase, finds JAY‑Z apologizing to a pregnant ex‑lover. The beat samples a film score to create a tender backdrop; Carter acknowledges his shortcomings with lines like “My problem is I love your little son like he was mine” and confesses that he won’t be around forever. The vulnerability he displays here and on “This Can’t Be Life” hints at the introspection that would later define The Blueprint and The Black Album.

The closing track “Where Have You Been” is the album’s emotional apex. Over T.T.’s melancholic piano and strings, JAY‑Z and Beanie Sigel address their absent fathers. Beanie’s verse culminates in a breakdown: “Do you even remember the tender boy you turned into a cold young man? Daddy left me, I had to use my streets to feed my family.” Jay confesses he shot his older brother at age twelve and wonders if his father would have left if he’d known the pain he’d cause. The song functions as a therapy session, bridging generational trauma with a plea for accountability. Its raw honesty anchors the album’s hedonism in human frailty and underscores why The Dynasty remains memorable.

Recording took place between late July and September 2000 at Baseline Studios in Manhattan. NBA player Malik Sealy, who owned the studio, was present when “You, Me, Him and Her” was laid down. When JAY‑Z and the Neptunes were in Right Trax Studios recording “I Just Wanna Love U,” Chaka Zulu called to request a second single for Ludacris’s debut; the Neptunes went downstairs and produced “Southern Hospitality” on the same night. Just Blaze used Logic software to create the beat for “Streets Is Talking,” an early example of digital production replacing hardware. No one else laid verses until six songs were completed, and only after “Guilty Until Proven Innocent” and “I Just Wanna Love U” were recorded did the team decide the project should be a JAY‑Z album rather than a compilation. Def Jam executives feared that a Roc‑A‑Fella group album would be hard to locate in record stores; using JAY‑Z’s name guaranteed shelf space.

Details about individual songs reveal creative quirks. Bink! bought Ten Wheel Drive’s “Ain’t Gonna Happen” record at a yard sale for five dollars and turned it into the sample for “1‑900‑Hustler.” Jay insisted on adding the elevator music that plays before Freeway’s verse, and Hip Hop (Kyambo Joshua) devised the hotline concept after listening to the Convicts’ “1‑900‑Dial‑A‑Crook.” Beanie Sigel originally planned to spit a verse on the song but gave his slot to Freeway, demonstrating the team’s willingness to share the spotlight. During the “Change the Game” video shoot, Memphis Bleek was upset because the crew wouldn’t let him ride a motorcycle; for safety reasons, they hitched it to a truck so it would look like he was riding. These anecdotes humanize the Roc crew, showing them balancing ambition with camaraderie and occasional silliness.

Yet the album’s importance lies less in its track‑by‑track consistency than in its role as a bridge. It captured a moment when JAY‑Z was transitioning from rapper to executive and when Roc‑A‑Fella was morphing from a boutique label into an empire. The roster overhaul introduced the public to Beanie Sigel, Memphis Bleek, and Freeway as serious talents, and it served as a recruiting poster for State Property. It also showcased a new generation of producers who would define early‑2000s hip‑hop. Just Blaze’s sample‑manipulation and towering horns, the Neptunes’ minimalist funk, and Kanye West’s soul chops all foreshadowed The Blueprint, released a year later. Roc‑A‑Fella’s history page highlights that Carter’s choice to work with these up‑and‑comers instead of his established collaborators helped give them platforms that would “become consistently involved in future Roc‑A‑Fella projects.” The album set a precedent for the crew’s historical run over the next several years.

Beyond its industrial impact, The Dynasty offers a snapshot of early‑21st‑century Black music culture. The album swerves between gritty narratives and aspirational fantasies, reflecting the dual realities of many black artists who were both survivors of poverty and new participants in the luxury economy. JAY‑Z’s lyricism captures this tension: he brags about Cristal and platinum Rolexes one moment, then confesses a fear of failure or bemoans an absent father the next. Beanie Sigel embodies the stakes of street life; his verse on “Where Have You Been” tears through the myth of the fearless hustler, exposing a child longing for guidance. Freeway’s frantic delivery on “1‑900‑Hustler” introduces a voice that would become synonymous with Philadelphia’s rap scene. Even Snoop Dogg’s cameo, with his laid‑back pimp persona, underscores how West Coast and East Coast styles were converging as the regional wars of the 1990s faded.

After all this, its imperfections become part of its charm. The posse cuts sometimes drown out JAY‑Z’s own verses, yet the willingness to cede space to his protégés reveals a generosity uncommon among major artists. The album’s filler tracks might have trimmed its runtime, but their inclusion paints a fuller picture of the crew’s dynamic—there were misfires as well as masterpieces. Today, songs like “Intro,” “I Just Wanna Love U,” “Streets Is Talking,” “This Can’t Be Life,” and “1‑900‑Hustler” remain staples in JAY-Z-driven playlists. They capture an artist at a crossroads, balancing solo superstardom with the desire to build a dynasty. The record also stands as a time capsule of an era when sample‑driven beats, posse cuts, and flamboyant hooks defined hip‑hop’s mainstream. More importantly, it provided the blueprint—both literally and metaphorically—for the sound and structure of early‑2000s Roc‑A‑Fella releases. In hindsight, its legacy is not just about the songs but about the doors it opened for a generation of producers and MCs who would shape hip‑hop for years to come.