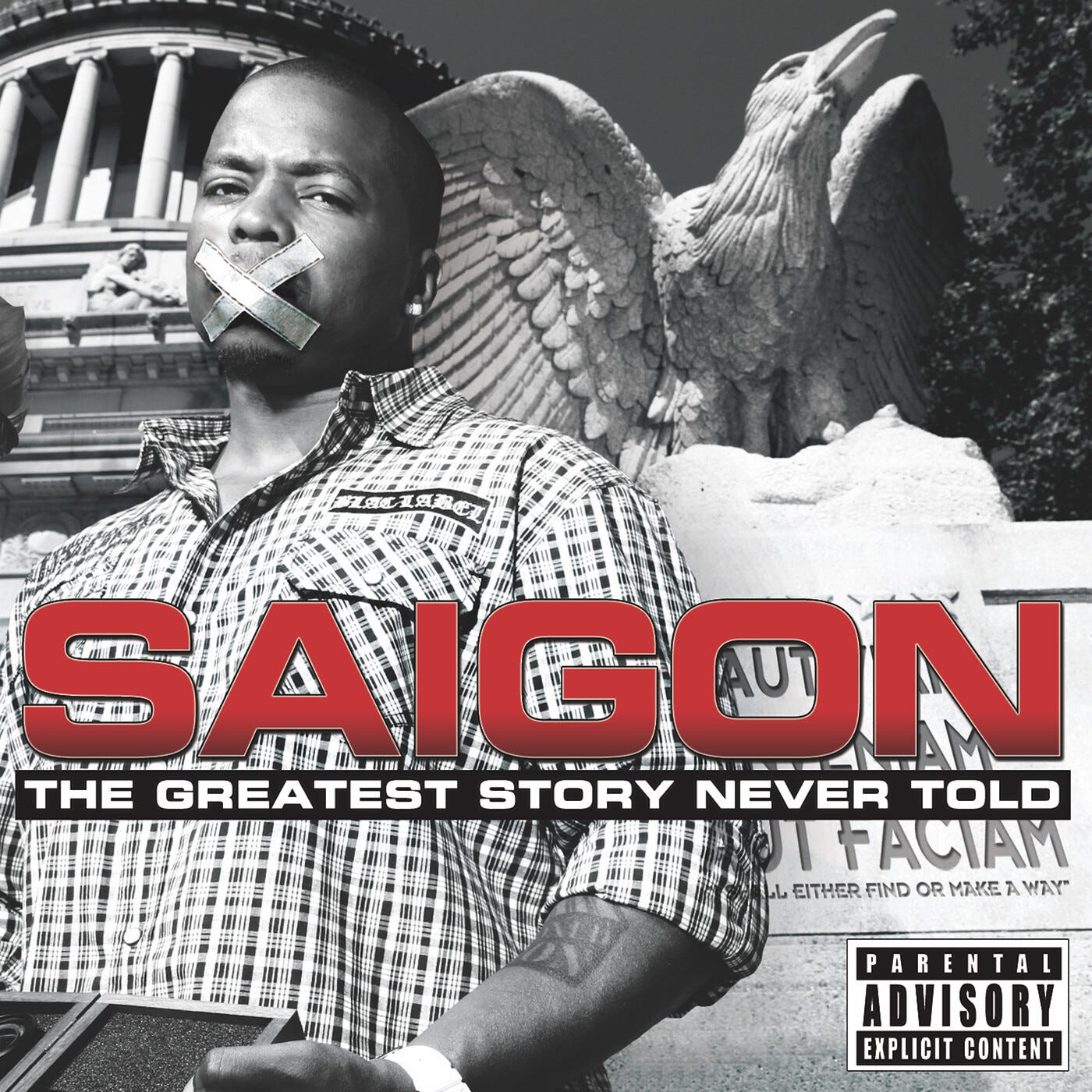

Anniversaries: The Greatest Story Never Told by Saigon

This MC went from prison battle raps to an Atlantic deal that tried to muzzle him. The Greatest Story Never Told carries every scar from that war. Just Blaze built a monument; Saigon needed a wire.

Born Brian Carenard, Saigon had been lied to by almost everyone who said they were going to help him, and by 2007, he had stopped pretending he didn’t know it. He’d signed with Atlantic Records three years earlier carrying the exact album he intended to make and the exact title he intended to give it. He’d cut his teeth rhyming with a convicted murderer in the recreation yard at Napanoch’s Eastern Correctional Facility, renamed himself after a Wallace Terry war book, and walked out of prison in 2000 with a debut mapped in his skull. Atlantic dangled a deal in 2004. Two months in, they pitched him a collaboration with Pretty Ricky. An executive told him, point-blank, to deliver three radio singles and then he could “bust your artistic nut on the rest of the record.” Carenard hired a lawyer to try to leave. Atlantic offered more stipends instead, keeping him signed, keeping the record shelved, keeping the buzz contained enough that nobody else could capitalize on it either.

That kind of institutional stalling eats a person from the inside. By mid-2007, Carenard was posting MySpace screeds calling the label a warehouse for ringtone merchants and calling himself the kind of artist their infrastructure was designed to suppress. He scrubbed the post when he worried it insulted Just Blaze, the executive producer he couldn’t afford to alienate. Blaze pushed back publicly, insisting the holdup was a sample clearance on “C’mon Baby” that Atlantic president Craig Kallman was personally handling. The correction mattered less than the spectacle. Here was a man with a completed debut, magazine covers, an Entourage cameo, an XXL Freshman nod, and still no release date, reduced to moderating his own grievances so the one person with leverage on his behalf didn’t walk away.

September 19, 2007, compounded everything. Saigon performed an impromptu set at a Mobb Deep show at SOB’s in Manhattan, where simmering tension with Prodigy detonated into a physical brawl. He swung on Prodigy, got chased out of the venue by thirty affiliates, and both camps posted competing footage. Prodigy was sentenced weeks later to three and a half years for illegal gun possession. Neither man emerged from the incident with clean hands. For Saigon, whose whole argument rested on not being the reckless person the industry assumed he still was, the footage was corrosive. Less than two months later, he posted a blog titled “I QUIT,” announcing his retirement. He told HipHopGame, “This is it. The Greatest Story Never Told … I guess you could say it was prophecy.” Blaze responded a week later by posting that he was finishing the album. Carenard rescinded his retirement within a month.

The Greatest Story Never Told landed in February 2011, seven years after his Atlantic signing, on Blaze’s Fort Knocks Entertainment through Suburban Noize Records. The label history trails the album like exhaust. You can hear it in the misfit between what Carenard needed and what Blaze assembled around him. Blaze was the executive producer, the political patron, and eventually the financial backstop who secured the masters when Carenard extracted himself from Atlantic in 2008 with full ownership of the recordings. That loyalty counts for something real. Blaze fought for the project when Carenard was too angry or too exhausted to navigate the politics himself. But Blaze’s maximalism as a producer and his impulse to frame Saigon as a blockbuster MC rather than the specific, prickly polemicist he actually is creates friction that dogs the record across its eighteen songs.

Looped female background vocals recur with a consistency that starts to feel like a production signature applied regardless of fit. Seventy-nine minutes is a long time to sustain the kind of voltage Saigon generates when he’s locked in, and the beat selection swings hard between registers without settling. After a Fatman Scoop station-identification skit, “The Invitation” drops on thick, blaring horns and a menacing vocal sample. Saigon declares himself the voice of “the poor and profitless” stuck in a metropolis rigged against them while Q-Tip handles the hook by listing correctional facilities the way he once rattled off jazz clubs on The Low End Theory. The beat carries genuine menace, and Saigon meets it by combining sentencing-guideline specifics with first-person testimony. He planned to hand out fake party invitations at live shows listing mandatory minimums for gun charges. His instinct was always to make the warning concrete.

That discipline lapses when the material bends toward radio. “Give It to Me” contradicts the combative posture surrounding it, and “Bring Me Down Pt. 2” sits on electric-guitar distortion that overpowers his delivery rather than supporting it. From “Clap” through “Believe It,” Blaze’s production drafts run generous and ornate where Saigon’s writing demands something leaner. One exception lands cleanly. The Kanye West and Blaze co-production on “It’s Alright,” with Marsha Ambrosius singing over a Luther Vandross sample, works. The warmth in her vocal performance matches Saigon rapping encouragement to single mothers raising children alone, telling women that a man who isn’t smart enough to stay can’t teach their children anything useful.

The record’s harder stretches hold up better. Saigon doesn’t have to perform range he doesn’t own. On “Enemies,” the streets get personified as a friend who gradually becomes a threat, and Saigon narrates the arc without euphemism or romantic distance. He’d been incarcerated for first-degree assault after shooting at someone in a bar. He didn’t need to invent the paranoia that saturates the writing. “Preacher” is angrier, directed at clergy who collected tithes from families reliant on Section 8 housing subsidies and used the money to finance personal mortgages, naming the five-thousand-dollar wigs and the inexplicable real estate, locking each accusation to a lived observation. “Oh Yeah (Our Babies)” walks through the abbreviated life expectancy of at-risk children in language that refuses to console, compressing the distance from umbilical cord to homicidal impulse inside a single verse. Saigon had a daughter born at the end of 2008 and recorded “Fatherhood” for her. That proximity between tenderness and dread runs through the whole tracklist without ever being smoothed into a tidy resolution.

Layzie Bone appears on “Better Way,” which folds a plea for different choices into a production bed warm enough to pass for an anthem without entirely becoming one. The guest roster, including JAY-Z, Swizz Beatz, Black Thought, Devin the Dude, Q-Tip, Faith Evans, Raheem DeVaughn, and Bun B, signals Blaze’s Rolodex more than Saigon’s natural habitat. JAY-Z’s verse on the “Come On Baby” remix had already been partially repurposed from a 50 Cent “I Get Money” remix years earlier. A recycled contribution from the biggest rapper alive, attached to a debut that couldn’t find a shelf. Saigon attracted marquee names and still couldn’t convert them into momentum. The names had calcified before they arrived.

The difficult thing about the finished record is that its flaws and its convictions are products of the same conditions. Blaze’s sprawling architecture came from protecting the project across years when trimming it might have meant losing momentum or sacrificing the guest appearances that justified continued industry attention. The tonal inconsistency, veering from Faith Evans leading a gospel choir on “Clap” to a vocoder-slathered hook on “Believe It” to the sparse menace of “War,” came from a production timeline scattered across sessions, studios, and shifting label politics. And Saigon’s refusal to modulate, the same stubbornness that kept him from recording the Pretty Ricky collaboration, meant the record remained uncompromising even when compromise might have produced a tighter, stranger, more durable piece of work.

He told the Village Voice that “Preacher” was the first song he brought to the project. A song about religious graft bankrolled by the poverty of his own childhood. That’s the project’s actual center of gravity, and it has nothing to do with redemption narratives or conscious-rap branding. Carenard grew up in Brownsville, served time for a violent crime, got out, built a vocabulary from prison battle raps with a man who humiliated him, and then tried to cut a debut that told young people the truth about sentencing laws and economic traps without pretending he hadn’t contributed to the same cycles he condemned. He ran a foundation called Abandoned Nation for children with incarcerated parents. The tension between accountability and indictment never resolves on the record, and neither does the tension between Blaze’s desire to build a monument and Saigon’s need to deliver a dispatch. The finished product houses both impulses without reconciling them. Fourteen years later, the argument persists. The album still costs what it cost.