Anniversaries: The People’s Champ by Paul Wall

Paul Wall never lets you forget where he’s from. In the broader mid-2000s hip-hop landscape, The People’s Champ arrived during the Southern rap explosion.

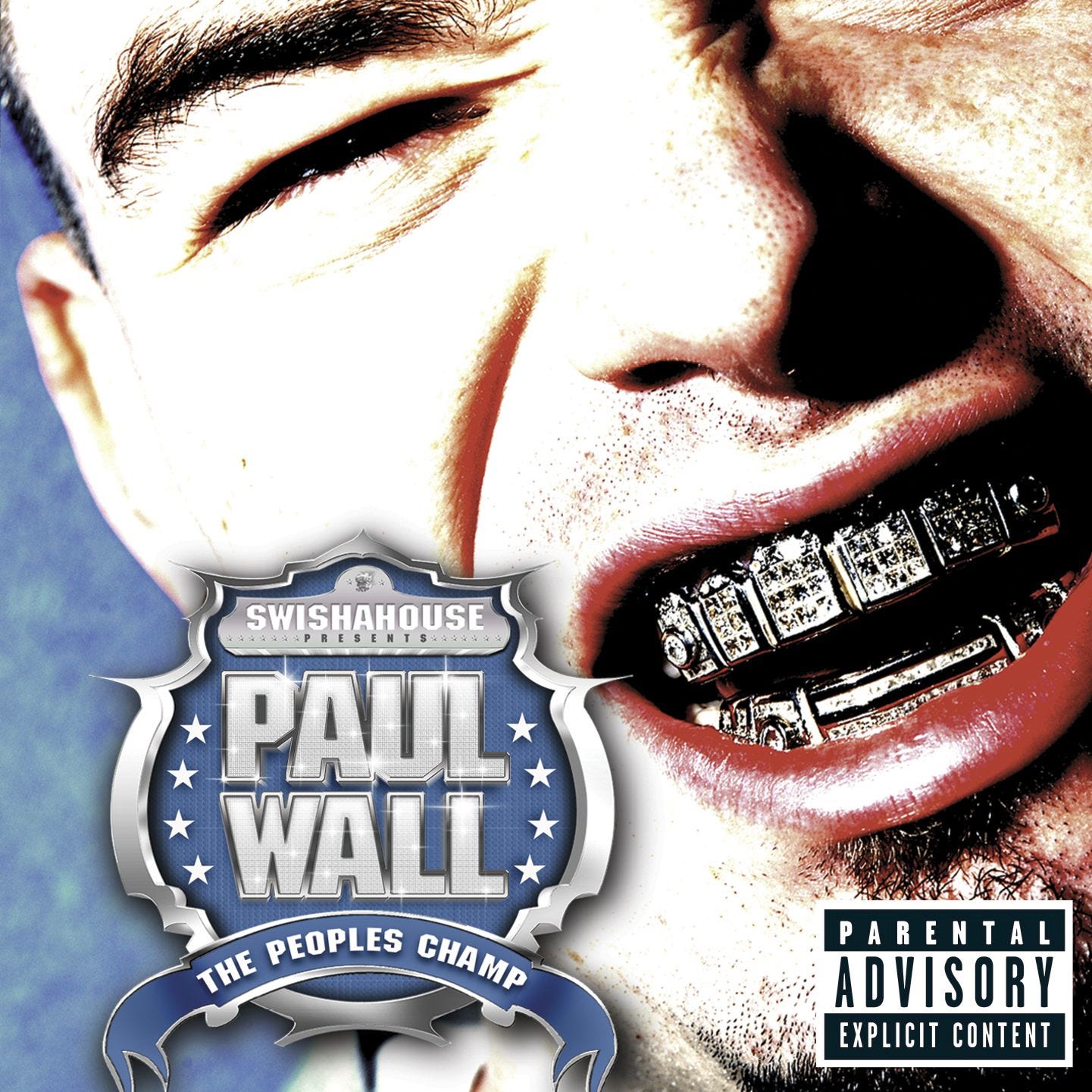

A Houston rapper with a platinum grill and a lazy drawl did the unthinkable—he knocked Kanye West off the top of the charts. Paul Wall’s The People’s Champ, his major-label debut, sold 176,000 copies in its first week and entered at #1 on the Billboard 200. It was a crowning moment not just for Wall but for Houston’s “trunk music” culture at large. For years, the city’s hip-hop scene had been percolating underground, fueled by candy-painted “slab” cars cruising slowly with subwoofers rattling—slow, loud, and bangin’, as the local slang defines it. With The People’s Champ, Paul Wall bottled that slab scene and served it to the masses. Remarkably, he also did it as a white rapper embedded in a predominantly Black hip-hop community, yet his race never became a defining issue. Instead of being marketed as a novelty, he was embraced as an authentic H-Town hustler who had earned his stripes alongside his peers. Wall occupies a rare space as a white MC—utterly entrenched in the culture and respected by hip-hop fans and legends of all shades. The People’s Champ shows why: it’s an album that captured Houston’s sound and swagger so faithfully that who he was mattered far less than what he was representing.

That Paul Wall could represent Houston so wholeheartedly was no accident. Far from a prefab “industry plant,” he had been grinding in the city’s rap circuit for years before his 2005 breakout. He was a University of Houston student (majoring in mass communications) and a lifelong rap fanatic who linked up with OG Ron C and Michael “5000” Watts’s Swishahouse camp as a teenager. In the late ’90s and early 2000s, Wall and his childhood friend Chamillionaire hustled their own mixtapes and even worked odd jobs to fund their musical ambitions (everything from washing dishes to working at a call center). “It took years of there being an independent scene just for me and Chamillionaire, Mike Jones, and Slim Thug to get major label deals,” Wall later recalled, emphasizing that his “overnight” success was anything but.

Equally important, he was an entrepreneur before he was a rap star. In 1998, he started designing and selling custom grillz—the diamond-studded mouthpieces beloved in Southern hip-hop—after striking up a partnership with Vietnamese jeweler Johnny Dang (aka “TV Johnny”). Wall earned local legend status as the go-to plug for grills long before he ever dropped a national hit. This unique résumé—college-educated hustler, mixtape mainstay, and grill impresario—gave him a down-to-earth credibility that set him apart. When he called himself “the People’s Champ,” it wasn’t just a catchy moniker; he’d truly come up from the people. He was the friendly neighborhood slab rider with a million-dollar smile (quite literally, thanks to those icy teeth) and a trunk full of knock. In a rap world that often expects white artists to foreground their race, Paul Wall did the opposite: he assimilated so fully into Houston’s rap fabric that many listeners forgot he was white at all. As Wall himself put it, “I’m just me. I just try to live my life as who I am”—and in Houston, “who he was” meant a tried-and-true member of the scene. That genuine local pedigree laid the groundwork for The People’s Champ to ring true to its title.

Musically, The People’s Champ is a vibrant snapshot of Houston trunk music at its mid-2000s peak. The production is steeped in the elements that defined the city’s sound: syrup-slow tempos, booming 808 kick drums, melodic basslines that make car interiors shake, and soulful, organ-laced melodies that nod to the influence of DJ Screw and the Screwed Up Click. Nowhere is this aesthetic more apparent than on the album’s breakout single, “Sittin’ Sidewayz.” Produced by Salih Williams of the local Carnival Beats crew, “Sittin’ Sidewayz” creeps along to a woozy organ riff and a thick, head-nodding groove—the kind of beat made for low-speed car stunting. It’s effectively a love letter to the slab life. The track even samples DJ Screw’s famous June 27th freestyle session, embedding Houston’s sonic DNA directly into its fabric. Big Pokey, a respected veteran of Screw’s clique, delivers the baritone hook: “Sittin’ sideways, boys in a daze/On a Sunday night I might bang me some Maze.” With that one line, he paints a perfect picture of Houston car culture—envision a candy-painted old-school Chevy crawling down a boulevard on a calm Sunday evening, speakers pouring out the silky soul of Maze ft. Frankie Beverly.

Paul Wall’s verses on “Sittin’ Sidewayz” are packed with H-Town iconography as well. He shouts out the Swishahouse and Southside legends, boasts about “candy paint drippin’ off the frame,” and describes his trunk rattling so hard it “bump[s] like chicken pox.” When he raps, “Say cheese and show my fronts, it’s more karats than Bugs Bunny’s lunch,” it’s a cheeky reference to the diamond-encrusted teeth he and TV Johnny were selling to half the city—a business Wall cleverly folded into his rap persona. Crucially, he delivers all this in his signature laid-back flow: a calm, conversational drawl that oozes Texas cool. He doesn’t need to speed up or get agitated; like a true slab rider, he lets the rhymes roll out as slowly as the car crawls. The result is hypnotic. “Sittin’ Sidewayz,” with its slowed-down vibe and trunk-rattling bass, became an anthem not just in Houston but nationwide, introducing millions to the art of swangin’ (cruising on swerving, wide “swanga” rims) and parking-lot pimping.

The rest of The People’s Champ reinforces and expands that vibe in all directions. Wall was savvy in curating his producers, pulling together a team that could hit various Southern rap sweet spots while keeping a cohesive Houston feel. A newcomer production duo aptly named Grid Iron handled a large portion of the beats, bringing a hard-edged consistency to the project. On “They Don’t Know,” one of the album’s bangers, Grid Iron weaves in literal pieces of Houston’s past—the beat famously samples classic tracks like DJ Screw and Lil’ Keke’s “Pimp Tha Pen,” UGK’s “Wood Wheel,” and Fat Pat’s “3rd Coast,” among others. Those samples aren’t just Easter eggs; they’re statements of lineage. Over this patchwork of H-Town hallmarks, Paul Wall and fellow Swishahouse alumnus Mike Jones trade brash verses aimed at anyone sleeping on their city’s grind. When Wall drawls about candy paint and big grills on “They Don’t Know,” it’s almost as if he’s saying: if you don’t know where this culture comes from, here are the receipts. In a single track, he bridges generations—from the early ’90s pioneers to the 2005 hitmakers—asserting that Houston’s rap identity has always been “trill” (true + real). The sound may be slicker now, the bass heavier, but it’s built on the same foundation laid by UGK, Screw, and the others name-checked in the music. It’s a clever way of expanding the trunk music aesthetic: by literally incorporating the old into the new, Paul Wall made The People’s Champ a celebration of Houston’s continuum.

Beyond Grid Iron and Salih Williams, the album’s production credits read like a who’s-who of Southern hip-hop, each bringing their own twist to Houston’s template. The opening track “I’m a Playa,” for instance, gets a jolt from Memphis: it was produced by Three 6 Mafia’s DJ Paul and Juicy J, who know a thing or two about crafting trunk-knocking anthems. Fittingly, “I’m a Playa” samples the 2004 syrup-sipping hit “I Got Dat Drank” (a collab between Houston and Memphis artists)—effectively linking Paul Wall’s album to the broader Southern “drank” (codeine) culture that both cities shared. The beat is faster and crunker than the usual Houston groove, and Wall adapts by coming more aggressive out the gate, rapping about candy cars and cupfuls of codeine with a guttural enthusiasm. It’s a hard club track, but still steeped in the Houston lexicon. A few tracks later, “Internet Going Nutz” brings in New Orleans flavor: producer KLC (of No Limit Records fame) lays down an up-tempo, almost bounce-esque backdrop as Wall boasts about having “the internet going nuts” for his music. In 2005, this was a forward-thinking concept—he was savvy on MySpace and message boards, building a viral buzz that paralleled his radio success. Over KLC’s skittering hi-hats and pounding kicks, Wall shouts out his own website and mixtape downloads, effectively claiming a new kind of trunk: the digital trunk of online file-sharing. Yet even on this distinctly non-Screwfied beat, he peppers his flow with Houston references and that trademark drawl, keeping the vibe rooted in H-Town.

Then there’s “Sippin’ Tha Barre,” produced by Houston’s own legend, Mr. Lee. As the title suggests, this track is a dedication to Houston’s infamous codeine-laced “lean” (Barre is another word for the syrup). Mr. Lee concocts a lush, moody soundscape built around a deep, slow-rolling rhythm—the musical equivalent of thick purple syrup drizzling in slow motion. Wavy synthesizer lines and a creeping bassline make the track feel almost woozy. Wall doesn’t disappoint in the subject matter: he pledges allegiance to his Styrofoam double-cup, rapping about “sippin’ the Barre” with an audible smirk. What’s notable is how seamlessly a song like this sits next to a more radio-friendly cut like “Girl” on the album. “Girl” (produced by duo Sean “Speez” Pennington and Travis “Continuous” Moore) was clearly aimed at broad audiences—it flips the Chi-Lites’ sweet soul classic “Oh Girl” into a candy-coated rap serenade. Over a chiming piano and a sped-up soul sample, Wall raps affectionate verses seemingly dedicated to a special lady. But in true Houston fashion, many interpreted “Girl” as an ode to his car—the one true love of any slab god. The genius of The People’s Champ is that both interpretations work. If you want a tender rap love song, “Girl” scratches that itch; if you’re a car fanatic, lines like “I done got candy on my ride” hit that much harder. Either way, the track gave Wall one of his biggest radio hits without him ever straying from the Houston trunk aesthetic.

Throughout these diverse sounds, Paul Wall’s presence is the glue. He’s a fundamentally likable rapper—the kind of artist who doesn’t dazzle with complex wordplay so much as he charms you into vibing along. On The People’s Champ, his flow stays in the pocket of every beat, sliding effortlessly over the chunky drums. There’s a subtle musicality to his drawl; he elongates syllables and hits his rhymes with a melodic lilt that always fits the fabric of the track. Wall has a clear lane, and he rides it with confidence. Cars, jewelry, codeine, hustling—these aren’t novel topics in Southern rap, but he delivers them with an insider’s delight, as if letting new listeners in on the city’s best secrets. He’ll rap in detail about swangas (84-spoke rims) and Vogue tires, or describe exactly how to outfit a slab with neon lights and hydraulic trunk lifts. He takes pride in being hyper-local. On “Trill,” a posse cut featuring Bun B (of UGK) and New Orleans’s B.G., Wall defers to the elder Bun on the opening verse—a nod of respect—then comes in with a verse that reinforces the Houston–Baton Rouge connection. He references candy cars and “staying trill,” linking himself to the legacy of UGK (who coined “trill”) while standing alongside them. It’s a moment of Wall showing he knows his place in the Southern rap lineage. He’s not trying to outrap a legend like Bun B; he’s repping his city next to him.

In the same way, Wall often paired with fellow Houston rising stars of that era—notably Mike Jones and Slim Thug—not to compete, but to complete the picture of H-Town’s dominance. By 2005, fans were used to hearing these three on tracks together (their breakout was the smash single “Still Tippin’” in 2004). Mike Jones was the loud, brash marketer with the unforgettable catchphrase phone number; Slim Thug was the towering, deep-voiced kingpin figure; and Paul Wall was the affable, witty glue guy with the endless grin. On The People’s Champ, Wall solidifies his standing among them. He might not have Slim Thug’s imposing presence or Mike Jones’s goofy hooks, but he has arguably the best pure flow of the trio and a knack for punchlines that stick. Where Mike Jones might repeat a simple line for emphasis, Wall will flip a clever metaphor (like comparing his trunk’s bounce to chicken pox, or likening his diamonds to cartoon carrots). And unlike many of his peers, he never runs out of Houston slang—he’s a verbal ambassador for his city.

The album’s guest list further bolsters its mission of putting Houston on the map while embracing the wider South. The features are carefully balanced. On one hand, you have local heroes: Big Pokey’s crucial appearance on “Sittin’ Sidewayz,” three members of Houston’s own Grit Boys on the rowdy “March N Step,” and cameos by lesser-known Swishahouse affiliates (like Cootabang and Archie Lee on “Got Plex”) that make the project feel like a hometown affair. Wall even included an uncredited interlude by Chamillionaire on the chopped & screwed disc—a nod to his old partner despite their split at the time. On the other hand, The People’s Champ smartly sprinkles in big national names, but always in a way that serves Houston’s narrative. T.I. drops by for a verse on “So Many Diamonds,” trading flamboyant ice-related boasts with Wall—a logical pairing, since both had obsessions with jewelry (T.I. was fresh off Urban Legend and Wall was literally selling grillz). Lil Wayne, then on the cusp of being the “best rapper alive,” comes through on “March N Step” with a rapid-fire verse, but interestingly, the track’s beat (courtesy of Grid Iron) keeps Wayne in Paul Wall’s world: it’s chunky and slow enough that even the New Orleans firebrand rides in a lower gear, splashing his syrupy drawl around. Freeway, the lone Northeasterner, guests on “State to State,” a title that hints at the song’s concept: connecting hustlers from Houston to Philly. Freeway’s aggressive, high-pitched delivery might seem an odd fit, but the track finds common ground in the theme of grind and shine across state lines, and Wall holds his own next to the Roc-A-Fella spitter.

Of course, the most high-profile collaboration on the album is “Drive Slow,” a song produced by and featuring Kanye West. Technically, “Drive Slow” was Kanye’s brainchild (it appeared on Late Registration), but Wall wisely included it on his album as well, recognizing it as a cultural bridge. Over Kanye’s soulful flip of a Hank Crawford jazz sample, Paul Wall delivers one of the most vivid verses of his career—a full 16-bar tour of Houston at night. “What it do? I’m posted up in the parking lot, my trunk waving/The candy gloss is immaculate, it’s simply amazing,” he raps in his opening bars, his voice smooth and unhurried. In just a few lines, he name-drops his CL Mercedes, details the neon glow and popping trunk of his ride, and brags that when he opens his mouth, the “sunlight illuminates the dark” from the bling. Kanye’s beat might have Chicago DNA, but Wall drapes it in Texas imagery. By the time he gets to “the disco ball in my mouth insinuates I’m ballin’,” you realize that The People’s Champ didn’t just capture Houston’s aesthetic—it successfully exported it. The chopped-and-screwed vocal effect at the end of “Drive Slow” (Kanye actually slows down his voice as an homage to DJ Screw) is like a final tip of the hat: Houston’s influence had permeated even the backpack-rap mecca of Kanye’s universe. And Paul Wall was the connective tissue.

Paul Wall never lets you forget where he’s from. Even on the closing track (fittingly titled “Just Paul Wall”), he’s repping the Parking Lot King persona—the guy with the loudest trunk and the brightest smile, posted up with lean in his cup and a Texas-sized chain on his chest. It’s a persona he wears easily, because it’s essentially an amplified version of his real self. That genuine quality is why The People’s Champ resonated then and still does now. In the broader mid-2000s hip-hop landscape, this album arrived during the Southern rap explosion. 2004–2005 saw the mainstream surge of crunk music from Atlanta, the national breakout of artists like T.I. and Young Jeezy, and simultaneous regional movements like hyphy in the Bay Area.

Houston’s moment in that sun was distinct: rather than hyper, club-oriented beats, the H-Town sound was slower and funkier, more about riding and vibing than jumping up and down. The People’s Champ epitomized that difference. It brought the “slab music” style to a mainstream that had perhaps heard of chopped-and-screwed remixes or seen the candy-painted low-riders on TV, but never experienced a whole album drenched in it. For hip-hop in 2005, it was refreshing and a little exotic—yet undeniably jamming. This wasn’t a case of a regional hero watering down his style for commercial acceptance. Quite the opposite: Wall doubled down on Houston’s quirks (screw music interludes, vernacular like “Tidwell” and “chunking deuce,” etc.), trusting that the quality of the music would translate. And essentially, it did. Songs like “Sittin’ Sidewayz” and “Drive Slow” became fixtures on rap radio and MTV, and suddenly kids in New York or L.A. were trying to decode words like “bow” and “barre.” The album ultimately went platinum, making it—as of its release—the last Houston rap album to sell a million copies in the CD era. This closed a chapter of Houston dominance, to be reopened only many years later (by Travis Scott in the late 2010s).

In retrospect, The People’s Champ endures as a classic of mid-‘00s Southern rap and a proud emblem of Houston’s culture. Its impact lives on in subtle ways. For one, it cemented Paul Wall as Houston royalty—a status he maintains to this day, even as major-label spotlights have faded. He’s weathered controversies and industry shifts and kept making music on his terms, always repping Houston. In 2021, he even released a sequel to “Still Tippin’” called “Still Sippin’” with Slim Thug and Lil Keke, explicitly aiming to recapture the old Swishahouse magic. The fact that fans welcomed it warmly says a lot about the nostalgia and respect attached to that era.

The People’s Champ quietly proved something in the larger hip-hop discourse: that a white rapper could break big without leaning on a white gimmick or virtuoso shock tactics. Paul Wall didn’t try to be an Eminem-style lyrical contortionist, nor did he play the role of a culture vulture—he simply immersed himself in the scene that raised him. By the time his album dropped, he had Bun B calling him “nephew” and Kanye West seeking him out for authenticity. Wall remains an anomaly precisely because he never pretended to be anything other than a local Houston MC who loves slab culture. His race was an afterthought to his fans; what mattered was his bona fides. And those bona fides shine on The People’s Champ. You hear it in the chemistry he has with every Texas artist on the record, in the confidence with which he drops regional slang, and in the obvious care taken to honor Houston’s musical lineage through samples and features.

If you go back and listen to The People’s Champ now, is’s like time-traveling to a sweltering evening in 2005, pulling up to a car meet at Houston’s Carros parking lot or outside a club on Westheimer. You can practically see the line of slab cars—candy red, blue, and green—with their trunks popped open, displaying neon signs reading slogans like “Texan Wire Wheels” or memorials to DJ Screw. You can smell the barbecue smoke and taste the syrup in the Big Red sodas. And you definitely can feel the bass, because Paul Wall made sure the 808s hit just right. The album’s legacy in Southern rap is secure: it sits alongside UGK’s Ridin’ Dirty and Geto Boys’ We Can’t Be Stopped as one of those albums that embodies its city. It may not have the overt socio-political heft of an OutKast record or the lyrical pyrotechnics of an early Lil Wayne tape, but The People’s Champ excels differently.

It’s an exercise in atmosphere and authenticity, in making the listener feel like part of the Houston experience. Every slab needs a sound to make its trunk wave—and Paul Wall provided an entire playlist. From the opener “I’m a Playa” to the chopped-and-screwed remix disc by DJ Michael “5000” Watts, the album invites you to ride slow. In doing so, Paul Wall truly lived up to his moniker. He became the people’s champ by capturing the people’s sound. And 20 years from its release, if you roll down your windows and blast “Sittin’ Sidewayz” on a Sunday night in Houston, you’ll likely still see heads turn and hands go up to chunk the deuce. The city hasn’t forgotten its champion. Paul Wall’s trunk may not shake the Billboard charts like it once did, but in Houston’s streets, it’s still “slow, loud and bangin’”—forever.