Assata Shakur and the Unfinished Struggle for Black Liberation

Shakur’s life exemplifies an unfinished journey toward freedom—one that continues to inform and challenge current generations to confront systemic racism, sexism, and the meaning of resistance.

From the moment Joanne Deborah Byron came into the world on July 16, 1947, in Queens, her life was shaped by the contradictions of a country built on liberation and bondage. Assata Shakur, as she would later call herself, spent her childhood shuttling between New York City and the Black South. In her memoir, she recalled living with her mother in Wilmington, North Carolina, during the Jim Crow era and later returning to Queens, where she felt estranged from both her classmates and the school curriculum. Teachers asked so few questions of Black children that she thought there was “something wrong with [them]” and described learning “sugar-coated” history that glorified the founders and portrayed George Washington as a paragon of honesty. Years later, reading works by W.E.B. Du Bois and other historians, she realized that Washington had owned enslaved people and that the American Revolution fought by “rich white landowners” had little to do with freedom for her people. Such disillusionment would motivate her life’s work; she sought knowledge beyond state textbooks and believed that learning history correctly is part of learning how to fight.

Shakur’s journey toward activism began in the ferment of 1960s New York. At the Borough of Manhattan Community College and City College, she joined protests demanding Black studies and was arrested during a campus occupation in 1967. She married classmate Louis Chesimard and moved to Oakland, where she gravitated toward the Black Panther Party (BPP). She was drawn not just to the audacity of Black men patrolling police with shotguns but to the idea of community survival. Panthers offered breakfast for children, free medical clinics, and classes in self-defense—programs that, as historian Mary Phillips notes, catapulted women into leadership roles. The party’s Ten-Point Program demanded jobs, housing, and education, but also insisted on the right of Black people to self-defense; for Shakur, it embodied a radical critique of capitalism and imperialism that she later described as clarifying that “the enemy was not white people but the racist capitalistic system.”

Gender was a decisive factor in Shakur’s choice of organization. Many nationalist groups promoted patriarchal notions of reclaiming Black manhood. By contrast, the Panthers accepted women as equals. The first female Panther, sixteen-year-old Joan Tarika Lewis, walked into the Oakland office and asked: “Y’all have a nice program and everything. It sounds like me. Can I join? ‘Cause y’all don’t have no sisters up in here,” then immediately inquired, “Can I have a gun?” Lewis not only received weapons training but later taught drill classes and led educational sessions; when male comrades refused orders, she invited them to the shooting range and “outshot ‘em.” The BPP’s early propaganda depicted women carrying rifles and running survival programs. As Shakur later explained, she joined the BPP because it was “the most progressive organization at that time” with “the most positive images [regarding] the position of women”; other nationalist groups were “so sexist… there was a whole saturation of [male] quest for manhood,” she recalled. For a young woman coming of age in an era when Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s infamous report blamed Black matriarchy for community problems, the Panthers’ critique of patriarchy was revolutionary.

Yet patriarchal assumptions persisted. Elaine Brown, who would become BPP chair in 1974, admitted that male Panthers often ignored women’s ideas; they “looked to women to help them, to take care of them, … but they did not look to women for their ideas.” Kathleen Neal Cleaver, the BPP’s communications secretary, bristled at reporters who asked about “a woman’s role in the revolution”; she replied, “It’s the same as men,” and later reflected that such questions deflected attention from the real issue: how to empower oppressed people to fight racism, militarism, and sexism. Panthers like Cleaver and Brown emphasized cross-racial solidarity, building alliances with the Puerto Rican Young Lords, Chicano Brown Berets, and other groups. Yet the state responded to this coalition with brutal force. Under J. Edgar Hoover’s COINTELPRO program, police and FBI infiltrators harassed, arrested, and killed Panthers, including Fred Hampton. This repression decimated the organization’s male leadership; as men were imprisoned or murdered, women filled the vacuum, demonstrating that feminism and anti-racism were intertwined.

Assata Shakur’s activism eventually led her into clandestine circles. Disillusioned by the BPP’s infighting and “macho behavior,” she joined the Black Liberation Army (BLA), a loose network of ex-Panthers committed to armed struggle against the U.S. state. With this shift came a new name. She adopted “Assata,” meaning “she who struggles,” and “Olugbala,” meaning “love for the people”; she chose “Shakur” from fellow BLA member Zayd Shakur’s family to signify kinship. Changing her name, she wrote, allowed her to cast off her “slave name” and affirm her identity as an African woman.

The BLA’s tactics placed Shakur squarely in the crosshairs of law enforcement. She was wanted on charges of bank robbery and weapons attacks, though many of these charges were dismissed. In 1973, her life changed irrevocably during a routine traffic stop on the New Jersey Turnpike. State troopers stopped a car carrying Shakur, BLA member Zayd Shakur, and Sundiata Acoli. A gunfight erupted; Trooper Werner Foerster and Zayd Shakur were killed, and Assata was shot in the arm and shoulder. Hospitalized and chained to her bed, she said troopers spat in her food, called her a “nigger bitch,” and attempted to coerce a confession by promising to save her life—a practice she dismissed as “divide and conquer.” She insisted that her hands were raised when the shooting began and that she never fired a weapon, a claim she maintained until her death.

The New Jersey court convicted Shakur of first-degree murder in 1977. She was sentenced to life plus thirty years and confined in a maximum-security prison. The state isolated her at Rikers Island for twenty-one months and kept her under constant observation even as she gave birth to her daughter, Kakuya, in 1974. She experienced not only solitary confinement but also the solidarity of fellow prisoners. In the county jail, she witnessed female inmates organizing to improve conditions; she noted that Black and Latinx women received harsh sentences for petty crimes while white women were bailed out. “If revolutionaries do nothing else, they must remember the women,” she later wrote, connecting personal suffering to a larger critique of racial and gendered criminal justice.

On November 2, 1979, a group of BLA and May 19th Communist Organization members executed a daring prison break, freeing Assata from New Jersey’s Clinton Correctional Facility without fatalities. After years underground, she resurfaced in 1984 when the Cuban government announced it had granted her political asylum. Fidel Castro described her as a fighter against racial oppression, echoing Cuba’s support for Black and Third World liberation movements. In Havana, she led an everyday life, learning Spanish, working as an English instructor, and writing her autobiography. The memoir, published in 1987 with a foreword by Angela Davis, wove together early memories, political analysis, and poetry. It includes the oft-quoted call to arms: “It is our duty to fight for our freedom. It is our duty to win. We must love and support one another. We have nothing to lose but our chains.” The cadence echoes a long genealogy of Black resistance from Harriet Tubman to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and resonates today at protests where activists chant her words.

In Cuba, Shakur lived in relative obscurity, yet her image took on mythic proportions. U.S. authorities vilified her as a fugitive; in 2013, the FBI placed her on its Most Wanted Terrorists list, the first woman to receive the designation. The New Jersey State Police offered a $2 million reward for information leading to her capture. Wanted posters circulated in airports and police stations, depicting her in a head wrap, staring defiantly. Meanwhile, within radical circles and hip-hop culture, she became a symbol of resistance. Public Enemy shouted “she’s on the run!” on their 1988 album It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, and rapper Common named a song after her in 2000, prompting controversy when he performed it at the White House. Black feminists and prison abolitionists cited her story as evidence of systemic racism and misogyny. When the Black Lives Matter movement originated in the 2010s, activists recited her prison manifesto at rallies. Young people wore shirts emblazoned with her face alongside those of Malcolm X and Angela Davis, framing her as part of a lineage of Black radical tradition.

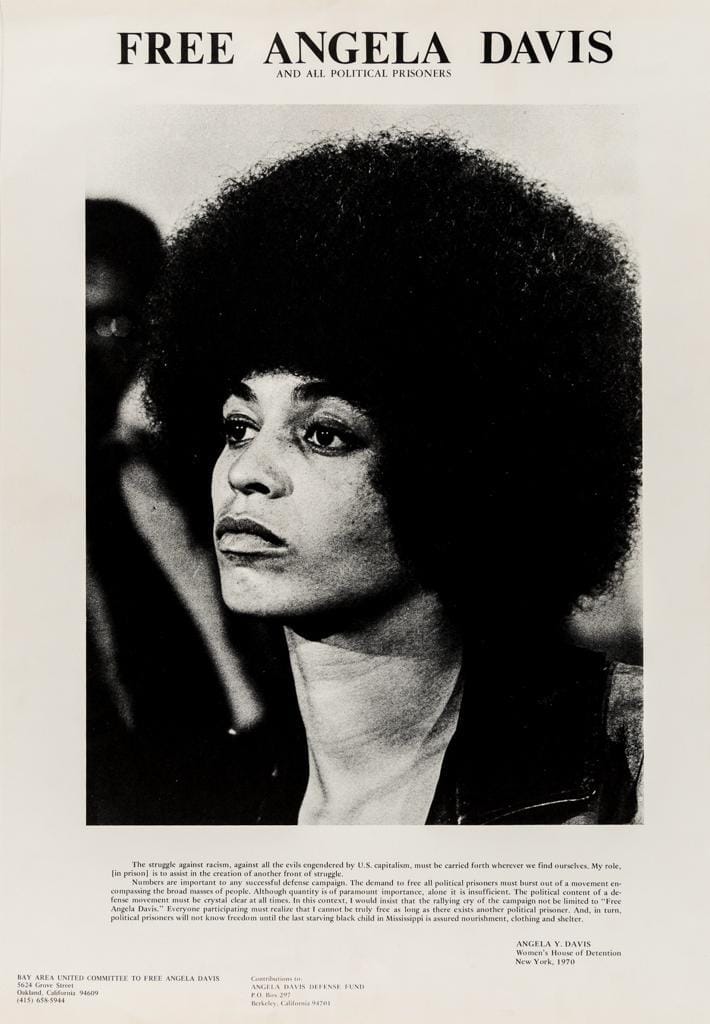

To understand how Assata Shakur’s life reveals the “long arc” of Black liberation, it is useful to compare her trajectory with other women who confronted state power. Angela Davis—a scholar and Communist Party member—was fired from UCLA in 1969 for her political beliefs and later placed on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list after firearms she purchased were used in a courthouse hijacking. Like Shakur, she went underground before being captured. Her arrest sparked global “Free Angela” campaigns, and she was acquitted of all charges in 1972. Davis’ case demonstrated the gendered dimensions of repression; she later noted that many Black women were arrested during this period because the government feared their political potential. Davis remains an esteemed professor and author who continues to advocate for prison abolition and collective liberation, illustrating how some women radicals can move from being vilified to being canonized.

Another parallel emerges in Joan Tarika Lewis. As the first woman Panther, Lewis balanced firearms training with artistic practice; she illustrated the Panthers’ newspaper alongside Emory Douglas and maintained that women “ran the BPP pretty much.” After male leaders were jailed or killed, women stepped into central committee roles and even chaired the party. The 1974 appointment of Elaine Brown as chair signaled that women could lead a revolutionary organization, yet it also provoked backlash from men who refused to accept female authority. Brown later wrote that men’s sexist attitudes and the weight of state repression ultimately drove her to resign. Lewis’ and Brown’s experiences highlight the dual pressures of patriarchy and police violence that shaped Shakur’s world.

Globally, women like Leila Khaled and Lolita Lebrón similarly embodied the contradictions of liberation and criminalization. Khaled, a Palestinian member of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, became famous after hijacking a TWA airliner in 1969 and an El Al plane in 1970. Although she was detained, she was later released and continued to advocate for Palestinian refugees, work on social programs, and serve on leadership committees. Like Shakur, she has been both celebrated and condemned—her portrait appears on posters in Beirut and Barcelona while her actions are labeled terrorism by governments. Lolita Lebrón, a Puerto Rican nationalist, led a 1954 assault on the U.S. House of Representatives to protest colonial rule. She served 25 years in prison and, after release, became an elder of the independence movement. These women’s lives, like Shakur’s, challenge the notion that resistance neatly fits into legal categories; the line between freedom fighter and criminal depends on who writes history.

Assata Shakur’s death in Havana on September 25, 2025, announced by Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, closed one chapter of this tumultuous journey. Obituaries revisited her biography: born in Queens, reared in North Carolina, politicized in New York, radicalized in Oakland, and exiled in Cuba. Journalists noted that she remained unapologetic about her struggle; she insisted she did not shoot anyone on the New Jersey Turnpike and framed her escape as self-liberation from an unjust system. Both supporters and critics recognized that her life symbolized the unresolved questions of Black liberation. Was she a murderer or a hero? A terrorist or a freedom fighter? The answer often depended on one’s position within a nation still grappling with structural racism and the legitimacy of armed resistance.

In the wake of her passing, debates about extraditing her resurfaced. U.S. officials reiterated calls for Cuba to return her, while Cuban authorities maintained that her asylum reflected their anti-imperialist stance. Meanwhile, younger activists drew inspiration from her life. For some, her decision to flee, start anew in Cuba, and write a memoir was an act of survival and self-definition. For others, her embrace of armed struggle remained problematic. The conversation revealed generational shifts: contemporary movements like Black Lives Matter emphasize non-violent protest, yet they also draw on Shakur’s critique of policing and incarceration. Her motto about fighting for freedom and loving each other appears on banners at protests against police shootings and mass incarceration, reminding participants that Black liberation is not just a policy demand but a moral imperative.

The story of Assata Shakur illuminates the unfinished nature of liberation. Her life spanned the period from the civil rights era through the age of mass incarceration and into the global Movement for Black Lives. She witnessed the early hopes of decolonization, the rise of Black Power, the crackdown of COINTELPRO, the explosion of hip-hop, and the resurgence of Black feminist thought. Her experiences echo across generations: in high school students who question sanitized textbooks, in young organizers who join community programs to feed children and treat the sick, in mothers separated from their children by prisons, and in activists who chant her words at marches. She left behind an image both feared and revered—wanted poster, exiled fugitive, revolutionary mother. That multiplicity is her legacy. Rather than offering closure, it invites us to ask, as she did, who our enemy is and what freedom requires. For Shakur, the answer lay in endless struggle, love for her people, and a refusal to accept the stories she was told. For us, her life challenges us to continue tracing the arc of liberation, knowing, as she wrote, that we have nothing to lose but our chains.

This was so informative, such a good read

Thank you!