August 2025 Roundups: The Best Albums of the Month

With releases from JID to Amaarae, here are notable releases in August that stood out to us as the best albums of the month.

Here’s the shape of August so far: early heat, a stacked mid-month, and a pop sprint at the end. GRAMMY’s calendar hints at that arc—openers from Metro Boomin, Reneé Rapp, and $uicideboy$, a busy middle stretch, then a finale crowded with marquee names. You can already feel the month tilting toward a few poles, with certain records drawing immediate critical love, with early notices putting it in the “must-hear” tier. That’s the field we’re pulling from. No spoilers here—only signals. The list that follows zeroes in on albums that moved the conversation and held up on repeat, across scenes that don’t usually talk to each other, but this month, keep trading the ball back and forth.

Seba Kaapstad, 4ever

A band known for expansive palettes pares the ideas into quick, no-nonsense songs. The multinational quartet still moves like a conversation between voices and writers who know each other well—South Africa’s Zoë Modiga, Eswatini’s Ndumiso Manana, and German partners Sebastian “Seba” Schuster and Philip “Pheel” Scheibel—but this effort here pushes for immediacy, with melodies that land fast and arrangements that leave air for phrasing and harmony to carry the weight. The dialogue between singers stays central, trading pledges and side-eye within compact hooks, while the rhythm section slips in sly breaks and handclaps rather than long builds. “Off Kilter” puts that design under a spotlight, a nimble back-and-forth sharpened by Tank from Tank and the Bangas; the groove snaps to attention then eases off, letting the vocal lines do the nudging. The group settles into warm morning light and quick-cut swing, favoring memorable turns of melody over extended solos. It’s the kind of record that trusts songwriting, not scale, where a through-line of empathy that fits the band’s cross-continental DNA. — Reginald Marcel

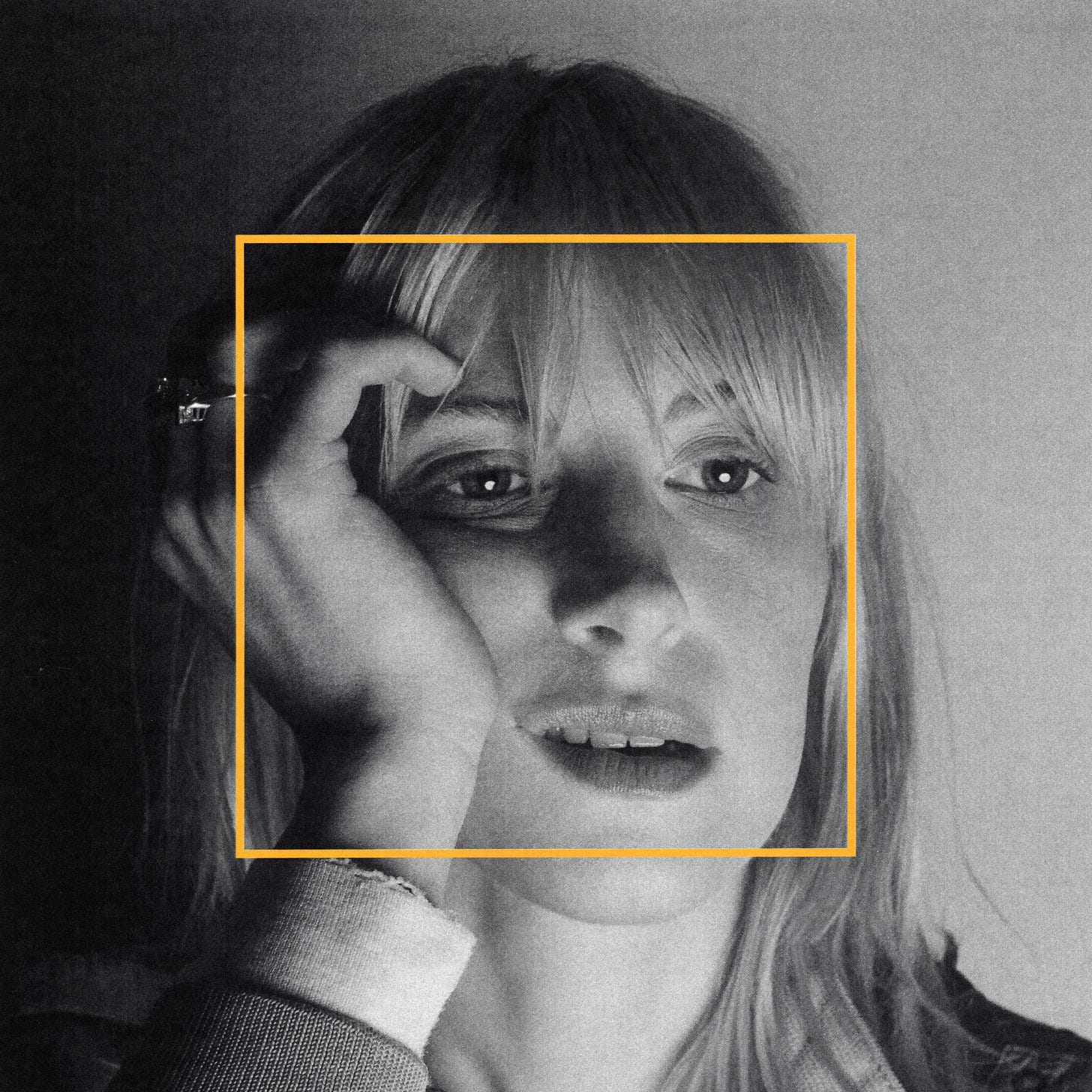

Hayley Williams, Ego Death at a Bachelorette Party

After years of fronting Paramore and two solo sets that traced emotional freefall and rebuilding, Hayley Williams suddenly dumped seventeen songs on her site and then platforms, a hard nucleus back to direct address where the writing toggles between self-audit and wry provocation, the songs feeling like dispatches she didn’t want sanded down by rollout. The draw here is specificity—on “Mirtazapine,” she names the medication. She writes to it without coyness, even admitting “You make me eat, you make me sleep,” the melody moving like a steady hand on the shoulder. At the same time, the verses catalog the symptoms and relief, and “Negative Self Talk” lives up to its title by turning the phrase into a chant that crowds the room, line after line testing the volume of that voice until the chorus feels like a boundary finally set. “Discovery Channel” flips a notorious hook—“You and me, baby, ain’t nothing but mammals”—and the lift becomes a joke with teeth, a way to talk about desire and agency without dressing it up, while “Mirtazapine” and “Glum” linger on private weather without hero pose, her phrasing clipped when the thought hurts and open when the air returns, the production staying out of the way so the writing can do the heavy lifting, which it does, repeatedly, in songs that read like marginalia from someone learning to narrate their own mind in real time. — Charlotte Rochel

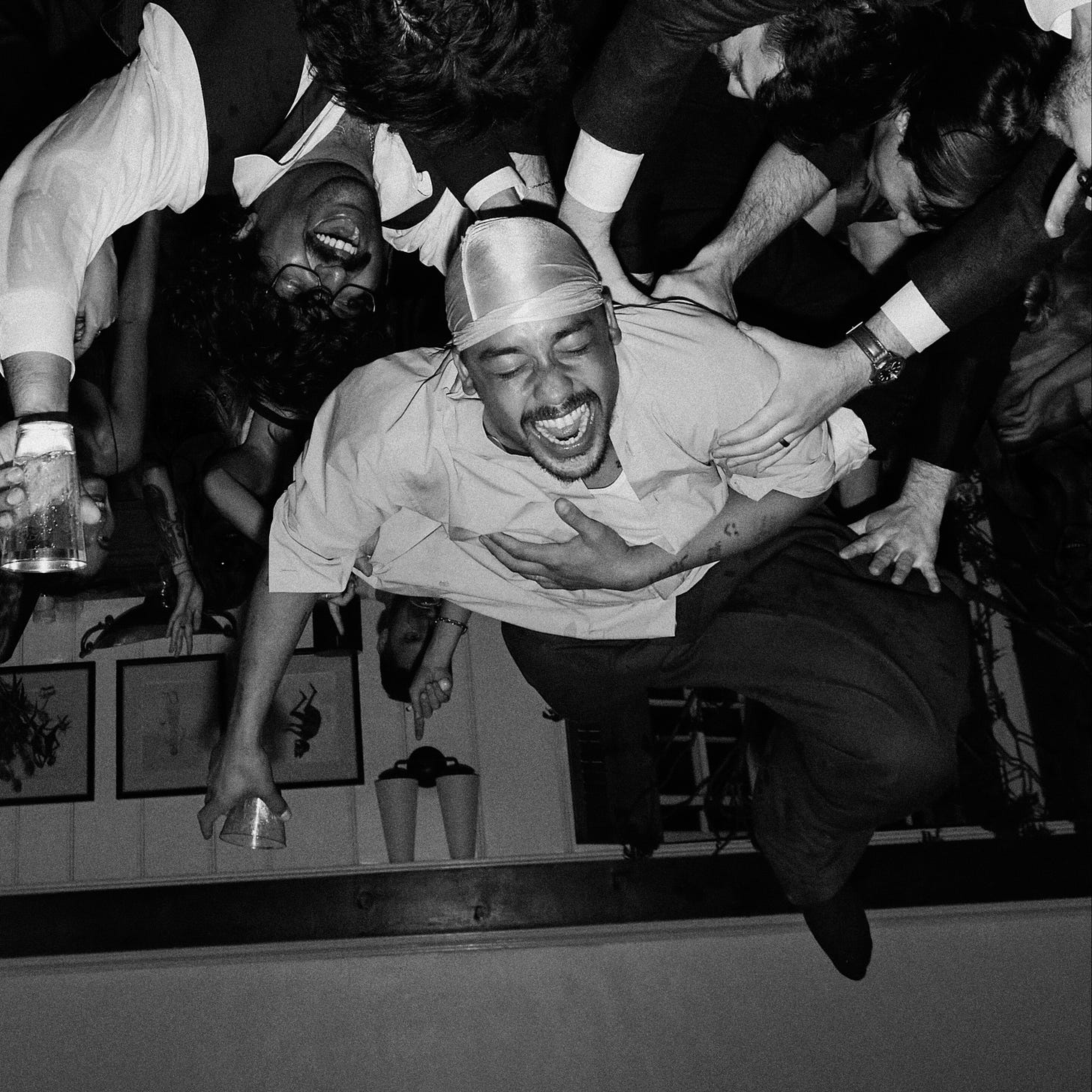

KAYTRANADA, Ain’t No Damn Way!

A two-time Grammy winner with roots in Montreal and Haiti, KAYTRANADA operates at a point where club culture and pop infrastructure already know his name. The new album trims the guest-list impulse and locks into utility: music built to move to and study to, short forms that stake a groove and leave space for the body to answer. “Space Invader” sets the tone with a nimble hook that sits on a lope rather than a sprint, and the rest of the set keeps that discipline, sketching ideas that click fast and linger without over-explaining. It works because the emphasis is on feel and edit, not flash; sections turn over on time, drums and bass carry the message, and the ear candy arrives as small turns rather than big reveals. The record lands like a public note to the faithful—“Something to move to, something to groove to”—and it doubles as a reminder that his tightest ideas hold even when he strips the vocals away. The confidence stems from the craft and timing, as evidenced by the freehand follow-up to Timeless (and its instrumental edition), where the artist articulates aloud what the project already implies about function and focus. — Jamila W.

Dijon, Baby

After the hard-won leap of Absolutely, Dijon returns with a second full-length built to pressure test what comes next. He writes from the life he’s been building, partner and new father in the house, and he bends the record toward that pressure with a jumpy, collage-minded approach that treats memory and domestic noise as usable parts of the kit. Songs pivot on sudden cutaways, voices pitch and splinter, and the drums lurch from human swing to clipped fragments that feel sampled even when they are played, a method he sharpened with Mk.gee and BJ Burton and kept flexible with Andrew Sarlo and Henry Kwapis. The effect is a steady argument for intuition over symmetry. Hooks arrive from the side, a shout becoming a refrain, a breath turning into a cue. When he asks, “Is it all just patterns packed inside,” the question doubles as a design note, because repetition here is never quite repetition, and the lyric keeps the music honest about what love and panic can do to form. A track like “Another Baby!” moves like a quickening thought, synth stabs and vocal yelps ricocheting without losing the thread of devotion, while “My Man” wears bright R&B vowels over scuffed tape edges so the tenderness has grain to it. Even when the room gets loud, the writing stays intimate, naming ordinary rituals and doubts with the clipped attention of someone catching ideas between feedings. The album’s core is that lived-in speed, and a tight circle of collaborators, a comfort with messy takes, and a belief that a family’s daily weather can power a pop record without sanding it down. — Tai Lawson

Amaarae, Black Star

Amaarae arrives here with real momentum. The Angel You Don’t Know turned a local cult into a global footprint, “Sad Girlz Luv Money” cracked the door wider, Fountain Baby proved she could build a world and tour it, then she stepped onto bigger stages as the first Ghanaian to play a solo Coachella set and leaned into the pop star she’s been writing toward. That’s why Black Star feels like the moment she chooses appetite as engine and writes directly to desire, control, and play. The songs are built for motion and face-to-face drama, switching between taunting invitation and delighted excess. “Starkilla” links Bree Runway’s bite to Starkillers’ club muscle, “Kiss Me Thru the Phone Pt. 2” pulls PinkPantheress into a sugar-wired techno sprint, “ms60” closes with Naomi Campbell’s cool poise as a statement of intent, and “S.M.O.” pulls on highlife ideas and swings with warmth, mixing sacred language with hedonist promise until the song reads like a ritual of consent and pleasure. She toys with pop memory, nodding to Cher and Gucci Mane while keeping the center of gravity in her own voice. She keeps everything playful, cutting, self-mythologizing, but specific about desire and power, which is why Black Star works as a portrait of power in motion, an artist testing how far clarity can go when pleasure is the subject and the pen keeps the rules. — Ameenah Laquita

Juicy J & Endea Owens, Caught Up In This Illusion

Endea Owens’ Juilliard pedigree and Cookout ensemble meet a veteran rapper who’s turned mixtape endurance into a decades-long brand. Primarily an instrumental piece, Juicy J raps in a measured pocket while a band with real swing moves around him, and the writing leans toward grown stakes, whether he’s talking custody runs in “Taking My Kids to School” or setting boundaries in “Litigation vs Loyalty.” Cory Henry’s keys and Kenneth Whalum’s horn lines answer the verses like trusted sidemen, and Nia Drummond’s voice steps in as conscience rather than gloss; “Drinks On Me at the Blue Note” reads the room and still makes space for a hook. Endea Owens isn’t here as ornament—her bass sets tempo and attitude, a reminder that she’s stamped big stages and earned major hardware—and that steadiness keeps the album honest about risk and restraint. The choice to put both names on the spine matters, where a rapper who knows momentum, a bandleader who knows form, and a set of tracks that let testimony sit next to groove without shouting for approval. — Nehemiah

Wildchild, Child of a Kingsman

Spot the scene and you can see it, mic in hand, the former Lootpack emcee working the front row and grinning like a dad proud of his section, which fits a project built after a long stretch given to raising his son Miles, known to most as Jack Johnson from Black‑ish, and you hear that decision echo in the writing’s emphasis on duty and inheritance. “Change for My 2 Cents” turns coins into conscience, counting out what value even means in a season of shortcuts, and the verses read like kitchen‑table talk sharpened into bars. “Season of Kingsmen” steps past nostalgia and into a pledge for how to carry yourself when younger heads are watching, and the line “less viral, more vital” lands like a mantra you can scribble on a sticky note and keep above your desk. Around those anchors, the record keeps naming the work. “A Kingsman’s Flowers” feels like handing roses while people can still smell them. “Wing Chun” flexes discipline rather than anger. “Bat Signal” calls the neighborhood together without sermonizing. Even when he lets guests into the room, he writes as a host who knows what the house is for, giving space and then tying every verse back to community, craft, and the idea that grown rap can still be warm and welcoming. There is bragging here, but it is the kind that points outward, to teachers, partners, and kids who need a map. — Harry Brown

Isaia Huron, Concubania

Raised in a South Carolina church and sharpened as a drummer, Isaia Huron moved to Nashville to build as a writer and producer. In the wake of a run of EPs and a loosies tape that hinted at range without settling the stakes, he makes a first full statement with a debut album that’s way more than just ‘solid.’ In recent interviews, he’s tied the idea to the mess of desire and faith, drawing a clear line between biblical cautionary tales and the way people move now, which gives the album a moral center without turning it into a sermon. That path explains the way Concubania is, where his writing stops auditioning and starts holding itself to account. On “I Chose You,” he writes from inside commitment rather than around it, describing the pull of impulse and the stubborn work of staying, and the verse-to-verse shifts feel like someone arguing with his habits in real time. “See Right Through Me,” a duet with Kehlani, pushes that tension further by turning confession into a two-way test of trust, as the exchanges read like carefully worded texts finally said out loud, and the pockets of silence between lines make the promises carry weight. He studies the language of uncertainty head-on—“I Think So?” and “Unsure” give indecision shape, not by hedging but by naming what doubt actually sounds like when you’re trying to choose better. “List Crawler” is a story song about curiosity and surveillance, brisk and specific enough to feel pulled from a real thread you wish you hadn’t scrolled, while “Thotful” turns defensiveness into a small character sketch. Across the set, Huron’s voice stays conversational and direct. He builds a record you can follow like a candid journal, where the details do the heavy lifting. — Harry Brown

Jenevieve, Crysalis

With Division and the slow-bloom of “Baby Powder,” it helped established Jenevieve as a singer who could bend retro touchstones without getting stuck in nostalgia, and the four-year step to Crysalis shows a more deliberate pen working with Elijah Gabor as executive producer to shape a humid, detail-forward R&B record where the rhythm section does quiet labor and the voice does the directing; the mission statement comes from her own notes about protecting energy and trusting instinct, which you can hear in how “Haiku” compresses confession into tight lines and stacked harmonies, how “Head Over Heels” rides a supple bass figure while slipping a Tom Browne “Charisma” sample into the pocket, how “Hvn High” lifts the tempo without sacrificing intimacy and moves like a night-drive scene in its Maya Table–directed clip, and how the title track threads resolve through a warm, analog-leaning palette, with backing parts kept simple so ad-libs can carry mood and the writing favors direct address over ornament, and by the time you pass through “Missing Persons” or “Enter the Void” you can hear the larger arc she described, a cocoon-to-clarity movement built less on spectacle than on control of tone and phrasing. — Imani Raven

Blood Orange, Essex Honey

Dev Hynes composed the majority of Essex Honey while in mourning at his family home, helping it materialize as an intricate palimpsest of memory and grief. He navigates oscillations between domestic stasis and psychological fragmentation, voicing lines such as “book stays out / stare through the page” and the exhausted avowal: “I don’t want to live here anymore.” On “Mind Loaded,” he reiterates a refrain that enacts both psychic burden and corporeal ache: “Still broken, can’t think straight, mind loaded, heart still aches … ‘Musil’ in my brain.” Joined by Lorde and Mustafa, he articulates an existential insight—“Everything means nothing to me / And it all falls before you reach me”—emphasizing how grief corrodes signification even amid collective gestures of care. “Vivid Light” stages a juxtaposition of flute and piano against a hip‑hop rhythmic frame, while “The Last of England” embeds a recording from his final Christmas with his mother before devolving into trip‑hop. The work shifts fluidly among sites of mourning within the domestic sphere, creative inertia within rented studio confines, and contemplative excursions into the countryside. Collaborators such as Lorde and Caroline Polachek assume equal prominence, forming a polyvocal environment through which Hynes negotiates bereavement. Essex Honey resists simplistic catharsis. Instead, it dwells within the liminal interstice between lament and tentative solace, allowing fragile motifs and elliptical lyric fragments to communicate the gravity of grief without recourse to dramatization. — Phil

The Amours, Girls Will Be Girls

Washington, D.C. sisters Jakiya Ayanna and Shaina Aisha grew from choir blend to tour-tested vocalists before stepping to the front under their own name. The album treats harmony as narrative stance, not garnish, so you hear two points of view find agreement in real time; when “That One Ex” snaps into the taunting line “I don’t mean to brag, but i be in my bag all 25/8,” the bite works as their blend stays tidy even as the text grins. “Clarity” uses the opposite energy, a steadier vow about naming needs, and Camper’s direction locks the tempo to the lyric’s plain talk so the refrain hits like a decision rather than a plea. Their pain favors small specifics—how you set terms, how you tell the truth when it costs you—and the production mostly moves out of the way, with bridges that lift just enough to make the final chorus feel like an answer. Years spent on PJ Morton’s stage trained them to project intimacy; that muscle shows up here in tight vocal stacks that act like underlines instead of fireworks. The net effect is a debut that reads with conversational detail and harmonies that argue and agree with a sister’s precision. — Brandon O’Sullivan

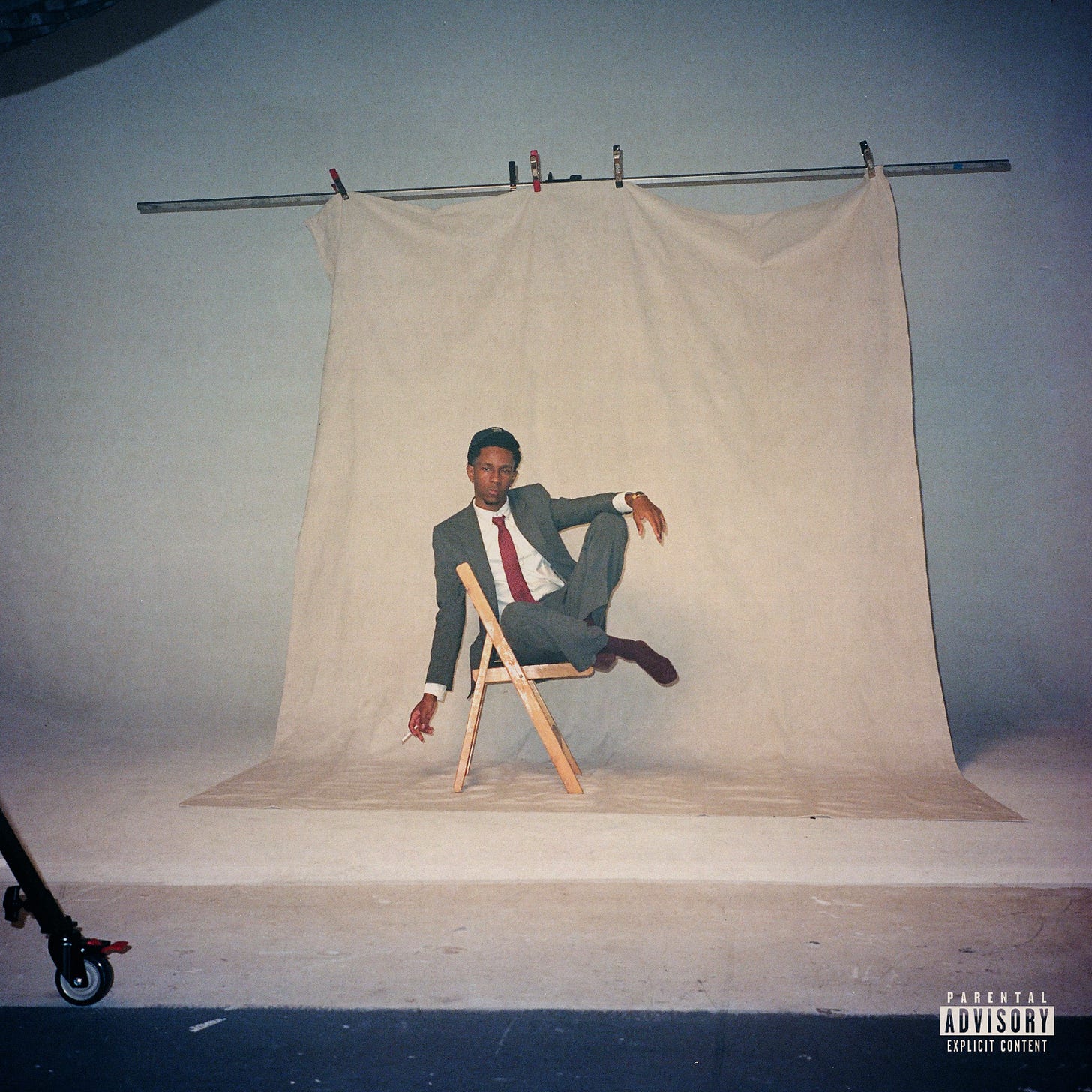

JID, God Does Like Ugly

A restless debut that put him on Dreamville’s map, a tougher sequel that sharpened his swing, and a sprawling family chronicle that scaled up his ambition. JID’s arc runs from the patient storytelling of The Forever Story to a ferocious reset built on a phrase from his grandmother, and after the summer jolt of “Bodies” with Offset and the scrappy Dollar & A Dream run, he steps into this record hungry and deliberate. On God Does Like Ugly, JID leans into consequence and bravado without losing craft, stacking knotty internal rhymes against hooks that land clean. The belligerent “YouUgly” sets the temperature for a project that pits chest-out boasts against private accounting, while “Glory” and “WRK” compress his precision into chant-ready refrains. “Community” pairs him with Clipse for a street-corner symposium where the writing rotates between watchfulness and confession, JID sketching the politics of favors and debts before Malice and Pusha spiral the language into cautionary parable, “Sk8” bends toward flirtatious release with Ciara and EARTHGANG without softening his grip, “VCRs” snaps into tense, clipped storytelling alongside Vince Staples, while “No Boo” and “Wholeheartedly” test a melodic register that keeps faith with R&B without surrendering the pen. Of Blue” with Mereba becomes a two-voice reckoning that moves from fragility to boundary setting, and the quietest turns feel earned because the record has already done the hard glare from here. The effect is a tougher, funnier writer who cuts the sermon with wry asides, a survivor’s album that reads as earned rather than performative. — Phil

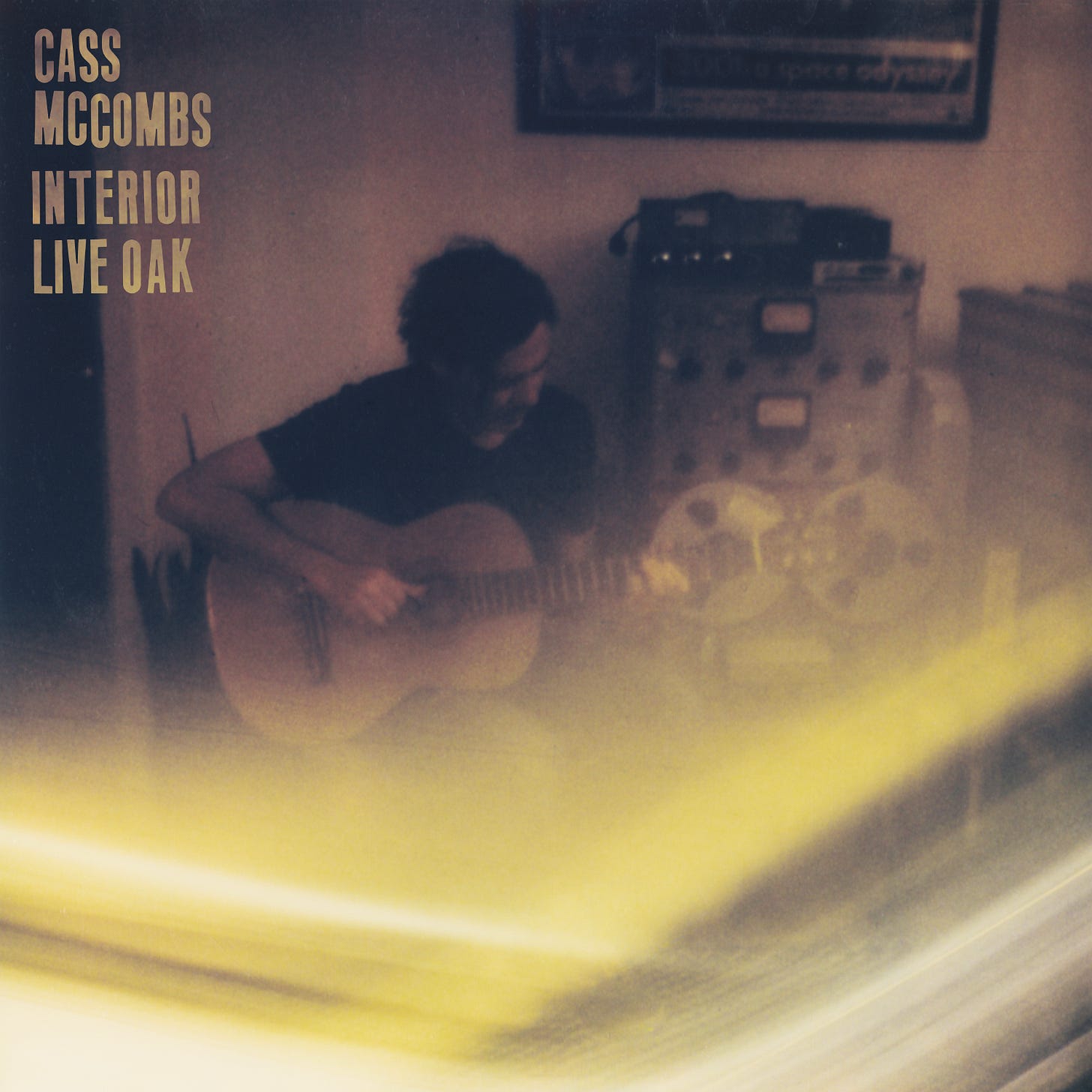

Cass McCombs, Interior Live Oak

Two decades into a catalog that prizes detail over display, Cass McCombs builds Interior Live Oak around names, places, and moral puzzles that unfold like short stories, the writing confident enough to sit with ambiguity and the performances relaxed enough to let small images do the heavy lift. “Priestess” holds steady on grief without leaning on big gestures, choosing specific ritual words that make memory tactile. “Peace” weighs compromise against conviction in plain speech that sounds like someone trying to talk themselves into calm, as “A Girl Named Dogie” sketches a character in a handful of gestures and lets the listener fill the gaps. “Van Wyck Expressway” uses a highway as shorthand for speed and escape while the melody slows the scene and pushes the eye to the shoulder, “Lola Montez Danced The Spider Dance” uses a historical figure to talk about performance and agency, and “Juvenile” checks the instinct to retreat into old habits and catches the sting without scolding. In “I Never Dream About Trains,” “I never dream about you curled up in that old army jacket/On the sand in Pescadero,” he’s saying absence in plain terms. No twist, no flourish. Just a note you carry. The arrangements keep open air around the words, folk and soul inflections moving in and out as needed, so the cadence of the line decides where the band lands, which makes the record play like field notes written with patience. — Oliver I. Martin

Earl Sweatshirt, Live Laugh Love

Earl’s path runs from the left-field sharpness of Doris through the inward focus of I Don’t Like Shit…, the fractured diary of Some Rap Songs, and the cryptic sparring of Voir Dire with Alchemist; the new record builds on that history while facing forward. The rollout leaned into mischief, but the songs are serious in their own way, sketching responsibility and doubt in brief scenes. “Tourmaline” holds one of the album’s clearest statements—“Struggle not a team sport”—and a line that places his priorities where they live now: “Keep my feet grounded for my sweet child.” “Live” walks the edge between defiance and exhaustion without reaching for a big thesis. “Infatuation” snaps phrases into place fast, more collage than lecture, and “Crisco” works as a broken-story monologue rather than a puzzle to decode. He keeps one eye on joy without pretending it cancels anything. In “Gamma (Need the <3)” he nods to Roy Ayers with a quick sun-reference, a small opening in an otherwise wary set. Around them sit titles that tell you the framing without overexplaining—“GSW vs Sac,” “WELL DONE!,” “Static,” “Heavy Metal aka Ejecto Seato!”—and the writing stays economical all the way through, which is the point. The record’s charge comes from how little he wastes. He marks fatherhood and pressure in clipped lines, lets the jokes and threats sit next to each other, and keeps the perspective tight enough that any warmth feels earned. — Nehemiah

KIRBY, Miss Black America

KIRBY recorded her long-awaited debut in a studio on the Dockery Plantation to underscore that sense of duty and declared that the album should take us to Mississippi. She has long written pop hits for others, but Miss Black America finds her telling a family story rooted in the Mississippi Delta, where her ancestors toiled. The 12‑song collection is a love letter to the rural South, exploring how land, church, and family shape one’s worldview. The title track offers the thesis outright: “You wanna free us pay them teachers like they senators … I made a million and I never went to Harvard,” she sings, turning a political demand into a personal brag. Big K.R.I.T. responds not as a guest star but as a neighbour, rejecting stereotypes and insisting that Black prosperity exists beyond performing for white comfort. Throughout, KIRBY keeps tasks and rituals at the centre—“Bettadaze” counts blessings over a rolling groove; “Mama Don’t Worry” reassures a parent with promises built on work rather than wishful thinking; “Reparations” uses the title word as a ledger entry rather than a slogan; and “Afromations” recites affirmations like children learning chores. Even the flirtatious “Thick n Country” stays grounded by tying sensuality to soil, while guest Akeem Ali adds hometown swagger without turning the track into a caricature. By writing from the perspective of a daughter and a neighbor, KIRBY turns her return home into a portrait of daily strength. — Imani Raven

Natalie Slade, Molasses

Sydney vocalist Natalie Slade follows her Eglo debut Control with a new full-length, Molasses. The writing leans into appetite and consequence, and the songs carry that tension without sermon or spectacle; you hear it most clearly on “Unquenchable Craving,” where she spells out the cycle with a clean, memorable couplet—“Sugar, sex, credit cards… what you need is not what you want, dopamine and dopa-don’t”—and then rides the phrase until it turns from confession into resolve. The production stands close to the voice and keeps instruments purposeful, but nothing calls attention away from the lyric; everything gives it traction. “Telephone” works like a late-night check-in rather than a set piece, its chords moving just enough to clear space for her phrasing to rise and hang; the restraint sets up the moments when she leans harder into a line. Across the record, you can hear the pairing with Sampology and contributions from Dan Kye, The DieYoungs, and Laneous as a set of choices that privilege feel and song shape, not sheen; it’s a collection that wears clarity as its character and uses repetition the way classic soul does, to test a claim until it holds. — Imani Raven

Ché Noir & The Other Guys, No Validation

Buffalo MC Ché Noir has established her artistic identity through an evolving mastery of narrative craft. She has already released two projects this year, and one of them is a sequel. Produced in its entirety by The Other Guys, No Validation extends this trajectory into a more rigorously autobiographical and communally resonant register. The inaugural track, “Incense Burning,” situates itself in quotidian domesticity, layering a subdued soul motif beneath reminiscences of “incense burning and wine and some music,” before receding to formative memories of “a nerdy kid in the hood, watchin’ Dragon Ball Z,” thereby interweaving cultural nostalgia with early entrepreneurial sensibilities. The structural centerpiece, “Katastwof,” features Skyzoo and Ransom, with Ché recounting delayed recognition in the line “a late bloomer in this game, they wouldn’t give me a chance” before reframing herself as “a fertile seed surrounded by the industry plants,” an agrarian metaphor of resilience and belated flourishing. Ransom concludes with reflective counsel: “Can’t add no days to your life, so just add some life to your days.” Three times a charm. — Harry Brown

Braxton Cook, Not Everyone Can Go

Braxton Cook’s résumé runs from Georgetown to Juilliard to touring with Christian Scott aTunde Adjuah, yet on Not Everyone Can Go, he brings that elite training back to personal questions about friendship, ambition, and mental health. The title track lays out his guiding principle: to reach a new stage he must let go of relationships and habits that no longer serve him. From there he writes a series of plainspoken vignettes: “Zodiac” uses astrological signs as shorthand for patterns in a relationship, “My Everything” openly asks a partner to be there without sugarcoating—“You said you’d always be there for me … my everything”—and “Harboring Feelings” admits to stockpiling resentments until a couple can name them and move on. “Weekend” shifts from confession to escapism with the invitation “Ima see ya on the weekend, I think we need a reset … just tell me where the beach is so we can get our feet wet”. Later, he uses “We’ve Come So Far” to count progress and remind himself of his mental health victories, while “BAP” includes a motivational monologue about sticking to one’s plan. As the record winds down, Cook returns to intimacy—“I Just Want You” pledges time and devotion, and “All My Life” with Marie Dahlstrom vows lifelong partnership. Throughout the project, he strikes a balance between ambition and gratitude, making room for growth by acknowledging what must be left behind. — Nehemiah

Nourished by Time, The Passionate Ones

Marcus Brown’s catalog has been building toward this: Erotic Probiotic 2 drew attention to the voice, the Catching Chickens EP showed the reach, and The Passionate Ones pulls love songs and work songs into the same room. He introduces the stakes right away. “Automatic Love” tests desire against collapse and throws out a line as plain as a diary entry—“my body won’t feel nothing”—which makes the risk legible without embroidery. “Max Potential” is even more direct, with the fear stated in seven words—“Maybe I’m afraid of the future”—then the song proceeds to measure that fear against the need to try anyway. The set keeps circling the cost of moving through the day and the pull of connection. “9 2 5” reads like a work memo written by a person trying not to disappear inside it. “Idiot in the Park” and “Crazy People” capture the city’s public theater without lasting judgment. The title track steps back and asks a simple question—“Am I a ghost?”—which turns the whole record into a check on presence, not performance. Across the album, he avoids the lifted-nose stance that plagues records about modern life. He keeps it close to the body and the block, switches between tenderness and blunt talk with no stylized bridge, and lets repetition do the work that thesis statements usually fake. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Deftones, Private Music

After nearly four decades of shapeshifting between nu‑metal and shoegaze, Deftones made their tenth album feel like both a personal exorcism and an invitation to join a cult of rebirth. The opener, “My Mind Is a Mountain,” sets the tone with a storm‑like metaphor about an inner battle, describing the climb of a mental mountain that demands endurance. Chino Moreno sings about storms, hearts, and fate while guitarist Stephen Carpenter builds eight‑string walls that envelop the listener. On “Locked Club,” the singer delivers a stark ultimatum, “Join our parade or be left out,” which defines the album’s tension between community and isolation. The record’s serpentine motif comes to life in “Ecdysis,” which likens personal transformation to a snake shedding its skin, while imagery of floods, fire, and plague suggests destruction as a path to renewal. Through these vignettes of transformation, Deftones manage to sound both timeless and urgent, turning their private rituals into a communal purge. — Oliver I. Martin

Lecrae, Reconstruction

Ten studio albums in, Lecrae looks back to the arc that made Gravity and Anomaly turning points, laying out a direct answer to the deconstruction stories he has told since Restoration. This time, the writing leans on testimony that treats prayer as a daily conversation and integrity as a muscle you train. The gauntlet drops early in “Tell No Lie,” where he snaps, “Say you keep it on your hip, don’t lie,” then widens the lens to the hunger for status and the small cheats we pardon in ourselves, and the song’s insistence on plain speech sets the code for the record. His verses move between confessional address and vows to show up when it counts. “There for You” pairs a pleading hook with promises that read like a late‑night text to someone who has run through every excuse, while “Better Sober” turns self‑control into a love language and refuses the easy brag. When “Headphones” brings in T.I. and Killer Mike, the conceit is simple enough to hold some weight, the old trick of blocking out the noise to hear the harder thing you need to do, and the writing keeps circling back to choice rather than mood. The faith songs are written like letters rather than lectures. “Pray for Me” asks without theatrics. “Politickin” with Propaganda reads the room and demands discernment over slogans over a West Coast bop. The back half keeps returning to durability and repair. “Cross The Ocean” uses distance to measure commitment, and “Still Here” closes the circle with stubborn gratitude. The through line is simple. Confess, tell the truth, stay. — Murffey Zavier

Gabe ‘Nandez & Preservation, Sortilège

A multilingual writer who once self-produced steps into a world where the beats arrive as puzzles from a veteran crate-digger. The partnership favors tension over shorthand: concise verses land in tight corridors of sound, and each beat organizes motion without spoon-feeding a mood. Guests drop in like pressure tests—Koncept Jack$on knots the cadence on “Hierophant,” billy woods bears down on “War”—but the center is ‘Nandez turning biography and reference into hard edges while Preservation keeps the floor steady under shifting scenes. You can hear the record’s build in the credits and settings recorded and mixed by Willie Green, with artwork that signals intent rather than branding; the album’s title means “spell,” yet what sticks is method. Songs tend to open with a clear image or a single term that becomes a hinge, then exit without drama once the case is made, and that restraint lets the bar work carry memory. If you want the roadmap for why this pairing clicks, it’s this. The writing assumes you’re listening closely, the production assumes you can handle nuance, and the pair meet in the middle with clean decisions you can hear. — Harry Brown

Chance the Rapper, Star Line

After the public beatdown of his debut LP, launching the Black Star Line Festival in Accra with Vic Mensa and working through a public divorce, Chance returns with an independently released album whose title points straight back to Marcus Garvey’s shipping company and the diaspora bridge it imagined. The record runs on specific arguments housed in songs: “No More Old Men” folds childhood Chicago snapshots into a plainspoken look at the life expectancy of Black men, “Drapetomania” flips the 19th-century pseudoscience into a liberation chant, and “The Negro Problem” leans on BJ the Chicago Kid to ground a piece about racial gaps in maternal health. “Tree,” with Lil Wayne and Smino, takes India.Arie’s “Video” as raw material and turns “tree” into a shield, a medicine, and a promise, with Chance directing the video to underline authorship. “Just a Drop” brings Jay Electronica into a measured exchange, and “The Highs & The Lows” formalizes the Joey Bada$$ partnership inside the album’s thesis. The executive producer is DexLvL, with additional work from Peter CottonTale, Rodney “Darkchild” Jerkins, Stix, Smoko Ono, Nate Fox, and Nico Segal, and a feature list that carries biography without padding. — Randy

Ghostface Killah, Supreme Clientele 2

Ghostface doesn’t posture here. He reports. The sequel lands as him returning to a world he named and writing new chapters with the same eye for people, places, and quick-turn scenes. “Rap Kingpin” sets the tone with a throwaway boast that still hits—“hitting mics like Ted Koppel”—and then the album moves through vignettes that feel lived-in rather than staged. “The Trial” plays like a courtroom exchange with Raekwon, Method Man, and GZA as characters, one of several tracks built from dialogue and situation more than moral. “Iron Man” and “Curtis May” point back to his own mythology while keeping the pen in the present, “Georgy Porgy” shows the soft spot he’s always allowed himself, and “Love Me Anymore” calls in Nas for a straight talk about loyalty and distance. Even the skits read like texture pulled from memory, not padding, which keeps the narrative pace up without resorting to plot tricks. The guest list is heavy across the album, but the verses hold because they are written as scenes—robberies recalled, friendships tested, a stray detail about reading by the pool that’s specific enough to be believed. It’s the same Ghostface method that made the first Supreme Clientele durable: dense naming, clipped action, and one-liners you can repeat without context. The difference is time. He sounds older, not slower, and the writing honors that. — Phil

Khamari, To Dry a Tear

The Boston‑raised, LA‑based singer put out a strong debut in 2023, then returned with a follow‑up that drops the defenses and writes directly from the push and pull between commitment and escape. The opener “I Love Lucy” starts with the line “Lucy wanna build a home up,” which frames the whole album as a negotiation between steadiness and drift, and by “Head in a Jar” he is picking through the claustrophobia that comes with being pedestal‑ed in a relationship, humming “You keep my head in a jar” as if naming it might shrink it. The writing keeps toggling between small domestic details and the big questions no one solves alone. “Close” carries the ache of being in the same room and still out of reach, and it reads like a long text you draft and delete a dozen times before sending. “Sycamore Tree” braids a memory of D’Angelo into a vow to grow up without getting hard, and the lyric questions are blunt rather than poetic fancy, the kind you mutter when the house is quiet and you finally let yourself be honest. Across these songs, he builds a patient emotional vocabulary from simple words, trading in faces, rooms, apologies, and the little tics that make a romance feel specific, and the melodies follow the writing rather than the other way around. The record earns its title by sticking with discomfort until it turns into a decision, and by the end, you can hear a young songwriter choosing candor over cool. — Phil

Lila Iké, Treasure Self Love

The road runs from Christiana to Kingston to global stages, and after a standout EP and a run of singles, Lila Iké finally delivers a first full album that treats truth‑telling as a daily habit and romance as a place where grace has to be practiced, not just preached. The writing puts confession up front. “Too Late to Lie” says the quiet part out loud with “Just say goodbye, it’s too late to lie,” and the verses list the small betrayals that add up to a break, turning plain speech into a kind of relief. “Romantic” flips a classic phrase into a call that is both playful and firm, repeating “I’m on a romantic call” while drawing a line around what attention should feel like. “He Loves Us Both” handles a messy triangle without cheap shots, staging a grown conversation rather than a victory lap, and “All Over The World” nods to diaspora pride with the steady certainty of someone who knows exactly where she is from. Even the lighter cuts keep their footing. “Fry Plantain” ties everyday joy to memory and hunger, “Scatter” lets desire talk without fronting, and when “Brighter Days” shows up, the hope sounds earned, not assumed. The best part is how often she writes in the second person, speaking to the lover, the rival, the fan, the self, and trusting clear language to carry feeling. It is easy to follow because she refuses to hide in pretty phrases. The songs say what they mean, then they stand on it. — Ameenah Laquita

Evidence, Unlearning, Vol. 2

Known for grey-skied introspection, Evidence lets more light in without losing detail. Evidence leans into close-miked cadences and leaves seams visible, so you hear choices as they happen, and the title reads like a working method rather than a slogan. The first words set the stance, “Set the autopilot, cruising speed,” and then the record goes about proving that comfort is not the plan. Beats from The Alchemist, Conductor Williams, Graymatter, Sebb Bash, C-Lance, and others keep the palette varied while he centers the writing on reassessment, the kind that turns a simple couplet into a pivot point. Guests show up as sparring partners and timekeepers rather than scenery, with Larry June, Blu, and Domo Genesis nudging tempo and tone so the verses move from laid-back inventory to clean-lined resolve. Hooks are spare and efficient, often a single phrase held in place by a drum accent or a small chord change, and the mixes keep his vowels dry enough that the punchlines hit without echo. What distinguishes this volume is the ease with which he folds new colors into an established grammar, a small surprise in every beat choice, and a clearer camera on the same street. It reads as growth. — Murffey Zavier

D Smoke, Wake Up Supa

On Wake Up Supa, D Smoke uses a journal assembled in the aftermath of his mother Jackie Gouché‑Farris’s death. He opens with the title track, addressing people who refuse correction, and uses the rest of the album to examine faith, grief, and loyalty through dialogue rather than sermon. “Na Na Na” shows how he turns a hook into a roll call, rattling off family and collaborators LaRussell and SHERIE as if he were naming streets back home. “Fire” brings in poet aja monet, and instead of flexing technical skills, he lets her image‑heavy lines dictate his cadence, treating the song as a conversation about choosing hope over gang life. Je flips between celebration and caution: “Count Cha Blessins” lays out successes as items on a list, “Energized” dismisses people who drain his spirit, and “Jackie’s Triumph” drops drums. Hence, his storytelling about his mother carries without distraction. “So Good” brings PJ Morton and Tiffany Gouché together for an unabashed thank you to life, aligning with D Smoke’s assertion that he wants this album to make people who ignored him “wake up.” By anchoring each song in a named person or specific exchange and refusing to hide vulnerability behind bravado, he crafts a record that sits in on a series of heartfelt conversations. — Tai Lawson

iyla, Weeping Angel

iyla builds a voice through short forms—the sharp, heart-forward War + Raindrops and the more confrontational Other Ways to Vent, a run that also put her across from Method Man on “Cash Rules”—before arriving at a debut that turns private upheaval into plainspoken conviction. With Weeping Angel, it’s a record of grief after her mother’s passing, of the stubborn self-belief that follows, and of the messy negotiations between desire and boundaries. The writing pulls tenderness and steel into the same breath. “Corset” sets the tone with rule-setting language and astrological self-inventory to “read the signs,” as “Overboard” uses the pull of water as a map for obsession and second thoughts, not with florid imagery but with moments of plain admission and recoil. The album’s most tender thread runs through “Blue Eyes,” written in the shadow of loss and carried by the hope that memory can still be a refuge where the perspective stays personal, not performative. She writes her way toward steadier love, starting with “Twin Flame,” imagining the version of partnership that doesn’t demand constant triage, while “Wild” and “Strut” argue for autonomy without turning it into a slogan, each one favoring decisive phrasing over posture. Even when she blurs sacred and sensual on “Ave Maria,” the line is less about provocation than self-permission, a reminder that devotion and embodiment can share the same room. Weeping Angel is direct, sometimes playful, sometimes cutting; images arrive only when they earn their keep, and what ties it all together is her insistence on naming things (hurt, want, lines in the sand) and trusting that simple, exact words can hold big emotions without decoration. — Imani Raven

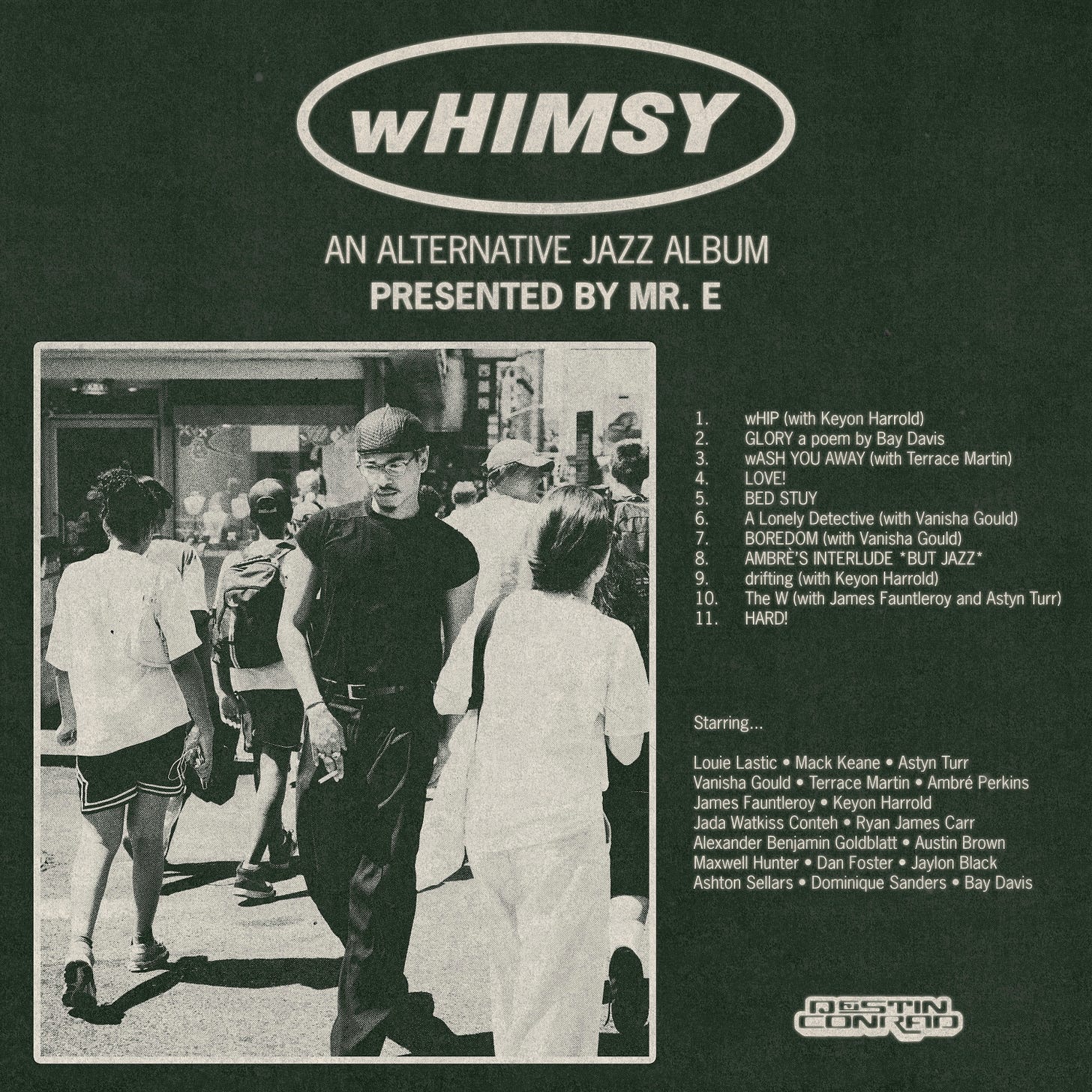

Destin Conrad, wHIMSY

As an R&B writer for Kehlani and others, Destin Conrad became known for streamlined hooks with conversational vignettes. Coming off of Love On Digital, wHIMSY abandons any hint of formula and uses a spare jazz backdrop to spotlight the intensity of his words. He calls it an “off the cuff, free idea” and treats it as a passion project, showing how far he can go by narrowing his focus to small acts and precise sensations. The album’s centrepiece, “wASH U AWAY,” opens with the unguarded line “I left your crib this morning and I smell you on my neck,” a sensory marker that makes the narrator’s internal argument about whether to cling or let go feel lived rather than imagined. Elsewhere he uses micro‑scenes to anchor his themes: “wHIP” reduces a relationship to the drive back from a night out; “BED STUY” shrinks a city down to a single neighbourhood; and the spoken‑word “GLORY” by Bay Davis reframes surrender as something safe (“Wanna show you how safe surrender can be when it’s holy … And my God, how selfish we’d be to keep all this glory to ourselves”). Even the lighter songs carry sharp edges: the plea on “LOVE!” (“Love, can we talk? … Is it really hard? Wanna make it mine”) and the deadpan complaint in “BOREDOM” (“You’re so far and you’re so boring”) refuse to generalise. By stripping away production flair and leaning on everyday diction, Conrad delivers a jazz‑infused project where each song feels like an extended note to someone specific, and the album’s whimsy lies in how unsentimental his reflections are. — Jamila W.