Bad Bunny Makes the Super Bowl LX Halftime Show About Identity More Than Hits

Traditional Puerto Rican imagery and community signifiers appeared front and center. Bad Bunny's performance was widely seen as a historic moment for Latino representation on U.S. prime time.

A Super Bowl halftime show has a job, and the job is simple. Gather a fragmented crowd. Sell them the fantasy that they are watching the same event for the same reason. Move fast enough that nobody argues with the premise. Cameras do the heavy lifting, stitching together crowd shots, pyrotechnic bursts, and close-ups of famous faces until 100-plus million viewers accept a shared reality that was never actually shared. Passive agreement is the format’s only demand, and it discourages reply. For roughly thirteen minutes, whatever the production chooses to put on screen becomes true, and everyone watching exists only to receive it.

Bad Bunny walked into that machinery at Levi’s Stadium on last night and bent it toward himself.

He opened with “Tití Me Preguntó” and kept the setlist anchored in his own catalog for the duration. “Yo Perreo Sola,” “Safaera,” “Eoo,” “Die with a Smile” with Lady Gaga, “Baile Inolvidable,” “NUEVAYoL,” “Lo Que Le Pasó a HAWAii” with Ricky Martin, “El Apagón,” “CAFé CON RON,” and the title track from DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, an album that had already won Album of the Year at the Grammys weeks earlier, making history. During the performance, the songs were in Spanish, as expected, because he had told the audience months earlier on Saturday Night Live to learn Spanish. Celimar Rivera Cosme signed the set live in the stadium. Captions trailed what they could, and the production kept moving.

That language decision is the load-bearing wall of everything that followed. Spanish, on this stage, in this slot, denied English the role of referee over what counts as legible. No pause came to teach anyone how to follow along. Comprehension was reassessed as the viewer’s responsibility, rewiring the usual performer-to-audience contract on live television. Instead of the telecast translating the set for a presumed monolingual crowd, it got cornered into the position of witness. Captions trailed behind the songs. Camera operators cut between choreography and crowd without the slow explanatory close-ups that a nervous production team would normally inject to smooth over unfamiliar material. Everything kept moving because nothing was waiting for permission.

That speed mattered. A halftime set built for pure frictionless consumption wants every second to be instantly legible, instantly clippable, instantly compressed into a social media highlight. His song selection jammed that conveyor belt. Reggaeton’s rhythmic structures demand sustained attention; they ratchet and shift tempo in ways that resist the three-second scroll. “Safaera” alone cycles through beat changes fast enough to disorient a viewer expecting one big hook per song. “El Apagón” carries political weight that sharpens every time it lands on a stage wrapped in national ceremony. Dropping both into a tightly managed television product pressed friction into a machine designed to eliminate it. Friction here was quality control. It told the crowd they were watching something with a gravitational center that did not exist to be extracted.

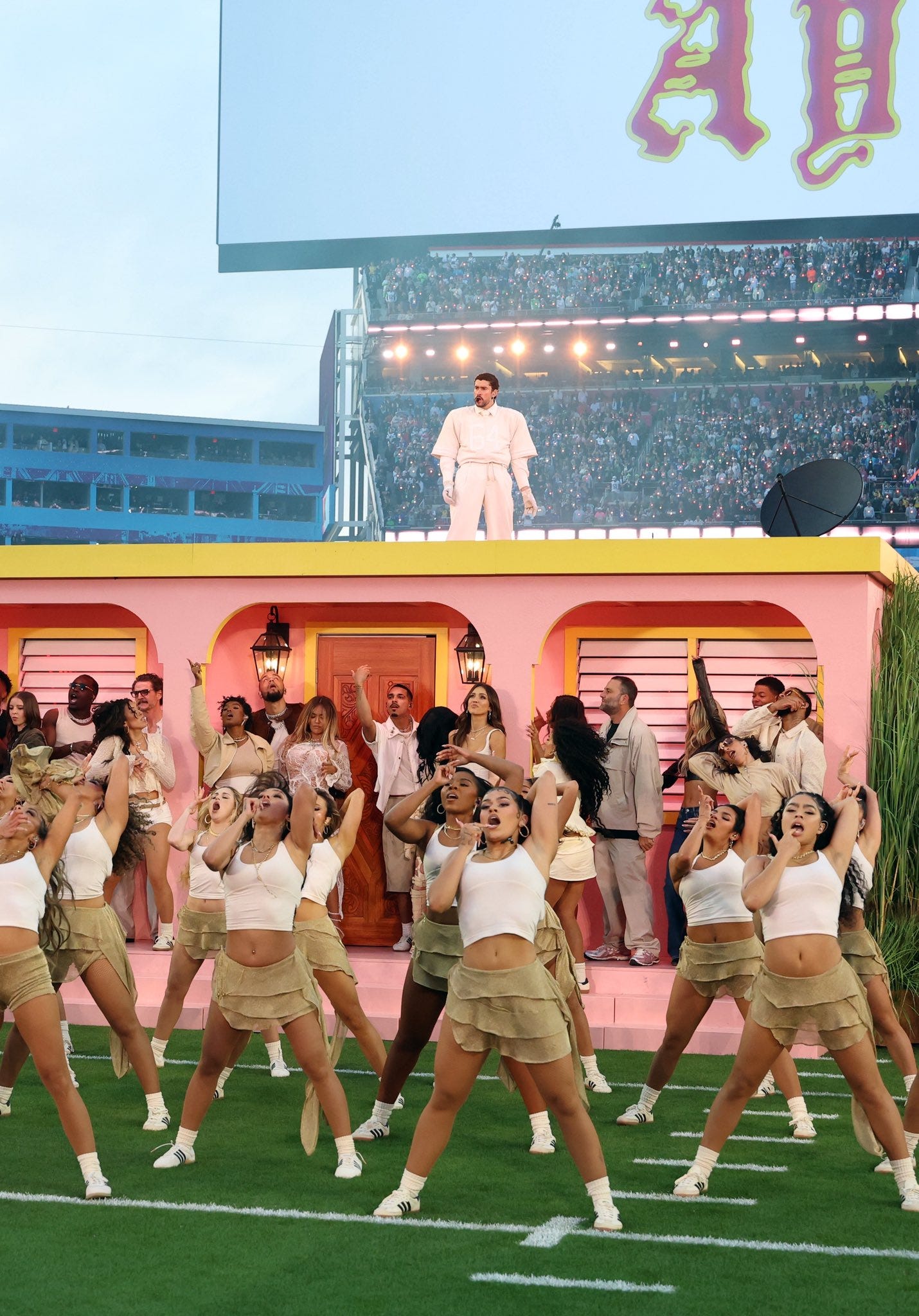

Staging pressed that same argument through a different pressure point. A traditional Puerto Rican casita anchored the set design, surrounded by vignettes drawn from daily life on the island and in the diaspora: dominoes players alongside piragua vendors, nail salons next to boxers, field workers in pavas sharing sightlines with a live brass band. Dancers climbed telephone poles during “El Apagón,” pulling from Santurce’s visual vocabulary. A wedding scene turned out to be real. Toñita from Brooklyn’s Caribbean Social Club handed Bad Bunny a drink inside the casita. None of these were decorative gestures. They reorganized what the camera was supposed to find valuable. Halftime productions usually reward spectacle without origin, footage stripped of geographic specificity so it can circulate as content for everyone and no one. By insisting on the ordinary rhythms of Puerto Rican life, this staging pinned the cameras to a domestic architecture that already exists inside the country hosting the Super Bowl, whether the telecast usually bothers to acknowledge that or not.

Lady Gaga joined for “Die with a Smile,” which may feel out of place for most (even though Bunny is a huge Gaga fan himself). She arrived inside a Bad Bunny show, bent to its gravitational pull, and left before her presence could redirect the arc. Ricky Martin appeared for “Lo Que Le Pasó a HAWAii,” a song whose political content keeps the temperature elevated even during a generational handshake. Every recent Super Bowl has rewarded the opposite of this discipline. Guest heaps, surprise overloads, and celebrity cutaways that replace musical focus with recognition-dopamine are the standard currency. He rationed that currency, pulling recognizable figures into his frame without surrendering the frame itself. Cameras caught Cardi B, Karol G, Pedro Pascal, Jessica Alba, and Alix Earle gathered in the casita, and the telecast predictably tried to re-center itself through their faces, cutting to reactions as shorthand for “you should care about this.” The set absorbed those cuts without flinching. Celebrity cameos were secondary to what the casita held.

That structure held an Afro-Caribbean core the design refused to flatten. Los Pleneros de la Cresta’s percussion grounded Gaga’s salsa arrangement in rhythms forged by enslaved Africans on the island, centuries before a single reggaeton beat dropped. Reggaeton itself descends from Jamaican dancehall’s dembow riddim, filtered through Panama and then Puerto Rico’s Black coastal towns. Cardi B, an Afro-Dominican and Trinidadian New Yorker, occupied the casita alongside Young Miko. Their position registered as the natural social makeup of the world Bad Bunny was constructing, which is why nobody introduced them. Nail salon vignette, pleneros' drums, dembow underneath every uptempo moment—Afro-Caribbean life was the floor, and the whole show stood on it.

Then the football. “Together we are America,” printed on the ball Bad Bunny held up. “God Bless America,” he shouted, and then called countries by name, south to north: Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Brazil, Colombia, Venezuela, Guyana, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Cuba, Republica Dominicana, Jamaica, Antillas, United States, Canada. Dancers carried each flag behind him. “We’re still here,” he said, and spiked the ball. A jumbotron message followed: “The only thing more powerful than hate is love.” Those gestures spoke fluent broadcast. They borrowed the event’s own vocabulary of unity and patriotism, phrasing that Super Bowl productions have relied on for decades to smooth over the contradictions of staging a national ritual inside a corporate product.

Taken alone, the football slogan is unremarkable. Placed after a Spanish-forward performance that declined translation and a roll call that named twenty-four nations and territories as “America,” it pressed a harder question. Who does that word include when the biggest television stage just got claimed without switching languages? The unity message did not erase the difference the show had already established. It named the difference and asked everyone tuned in to hold both at once. It also doubled as a practical shield. If the performance got attacked as alien, the prop sat there on the record, a visible rebuttal the broadcast had to carry whether it wanted to or not.

Attacks were already in motion before kickoff. Over 120,000 people signed a petition calling for Bad Bunny’s replacement with George Strait, arguing the halftime slot should “honor American culture” and avoid functioning as a “political stunt.” House Speaker Mike Johnson called it a “terrible decision” and suggested country singer Lee Greenwood instead. Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem warned that ICE would be “all over” the Super Bowl. Tomi Lahren and Marjorie Taylor Greene weighed in. Fox News ran the grievance on loop. Trump himself said he was “anti-them” and skipped the game. Turning Point USA staged a counter-event billed as an “All-American Halftime Show” featuring Kid Rock, with a website survey offering “Anything In English” as an option for preferred performers. Those reactions land differently when you notice what they actually protect. When people say “honor American culture” in response to a Puerto Rican artist performing in his own language, they are drawing a border around which images are allowed to occupy the most-watched television window of the year. They are contesting who gets to govern what the screen validates.

Bad Bunny had already named that tension before he took the field. At the 2026 Grammys, accepting Album of the Year for DeBÍ TiRAR MáS FOToS, he said: “ICE out. We’re not savages, we’re not animals, we’re not aliens. We are humans and we are Americans.” A Harris endorsement came in 2024. His U.S. tour got pulled over fears that ICE operations could target concertgoers. “There was the issue of like, fucking ICE could be outside [my concert]. And it’s something that we were talking about and very concerned about,” he told i-D Magazine. Trump’s response to Hurricane Maria drew his public criticism in 2017 and 2018. “NUEVAYoL” mocks the administration’s immigration posture directly, and none of it sits below the surface. Every political position is spoken, documented, and carried into the stadium through the setlist itself.

So when the cameras go live and the telecast starts filing this set into its usual categories, the friction between what the format wants and what the performer insists on becomes the story. Halftime’s structure tries to reunite its viewers while keeping them separated as spectators, linked only by the same image stream. Every person watching gets the same feed, and nobody gets to talk back. In that arrangement, whoever governs the images governs what the crowd is allowed to treat as real. Bad Bunny governed those images on this past Sunday night by declining to treat his identity as an accessory that could be swapped out for a more digestible version. Identity organized everything. Language stayed firm and staging read as home rather than set dressing. Guests reinforced his gravity instead of hijacking his arc. Political songs landed where they would cause the most productive discomfort, and the unity message acknowledged difference without flattening it.

Economics underneath that arrangement deserve one more beat. Halftime is a product engineered to monopolize attention outside ordinary working hours, pulling viewers deeper into a consumption cycle that treats artists as interchangeable units of excitement. One performer can be replaced by another as long as the spectacle stays frictionless. He fought that interchangeability by making his show harder to substitute. Spanish-language choices, Puerto Rican staging, and a song selection pinned to one person’s history and one person’s crowd grounded the set in a way the event could not easily neutralize. That does not eliminate commodification. The NFL still sold the ads, Apple Music still branded the show, and millions still consumed the feed. But it narrows the ways the telecast can pretend it was delivering a neutral product. The images carried a weight tied to a particular place, and they declined to be reduced.

Levi’s Stadium held 72,000 people on Sunday, with over 100 million more watching from home. Every one of them received the same feed, heard the same songs, saw the same casita and the same flags and the same football with its message printed in English. The setlist stayed in Spanish, and no apology arrived for that. And for thirteen minutes, the largest shared image stream in American broadcasting carried a culture that did not ask to be translated, did not wait to be understood, and did not bend toward the camera’s usual demand that everything on screen exist for the viewer’s comfort. Those images, for once, insisted on their own terms.