Blue Note Records 85: 85 Best Albums

Blue Note Records established artistic benchmarks through attention to detail and recording quality. These 85 albums document American musical innovation while inspiring future creative developments.

Founded in 1939 by Alfred Lion and Max Margulis, Blue Note Records shaped modern jazz through its uncompromising artistic vision. The label’s recordings documented the birth of bebop, the rise of hard bop, and jazz’s evolution across eight decades.

Blue Note’s signature approach combined artistic freedom with meticulous attention to sound quality. Recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder captured performances with unprecedented clarity in his Hackensack, New Jersey studio. The label’s striking album covers, designed by Reid Miles, created a visual aesthetic as distinctive as the music itself.

The albums in this collection span from Sidney Bechet’s early recordings to Robert Glasper’s modern fusion, highlighting Blue Note’s ability to preserve tradition while embracing innovation. Each recording represents a crucial moment in the label’s development and jazz history.

Wayne Shorter, Adam’s Apple

Shorter’s quartet creates spacious arrangements that highlight his compositional genius. The title track’s deceptively simple melody masks sophisticated structural elements. “502 Blues” demonstrates his ability to write memorable themes while maintaining harmonic complexity.

Kenny Dorham, Afro-Cuban

This album blends bebop’s harmonic sophistication with Afro-Caribbean rhythms. Dorham’s trumpet lines float above Carlos “Patato” Valdes’s congas on “Minor’s Holiday,” creating polyrhythmic conversations between jazz and Latin traditions. The modal structure of “Basheer’s Dream” anticipated developments Miles Davis would later explore.

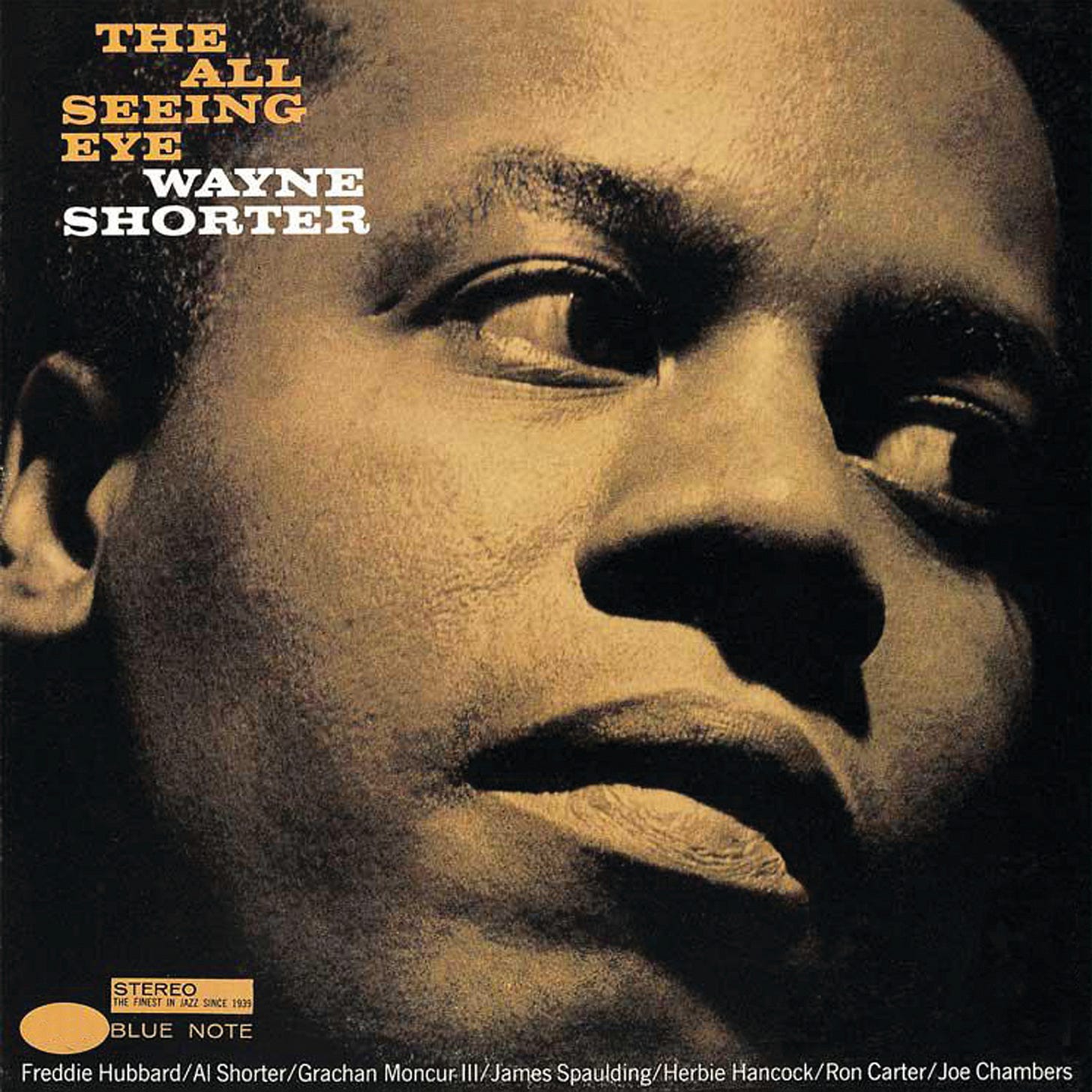

Wayne Shorter, The All Seeing Eye

Shorter’s ambitious suite explores extended composition and free-form improvisation. The 12-minute title piece builds tension through shifting meters and unconventional harmonies. Freddie Hubbard’s trumpet and Shorter’s tenor engage in dialogue that stretches conventional jazz language without abandoning structural coherence.

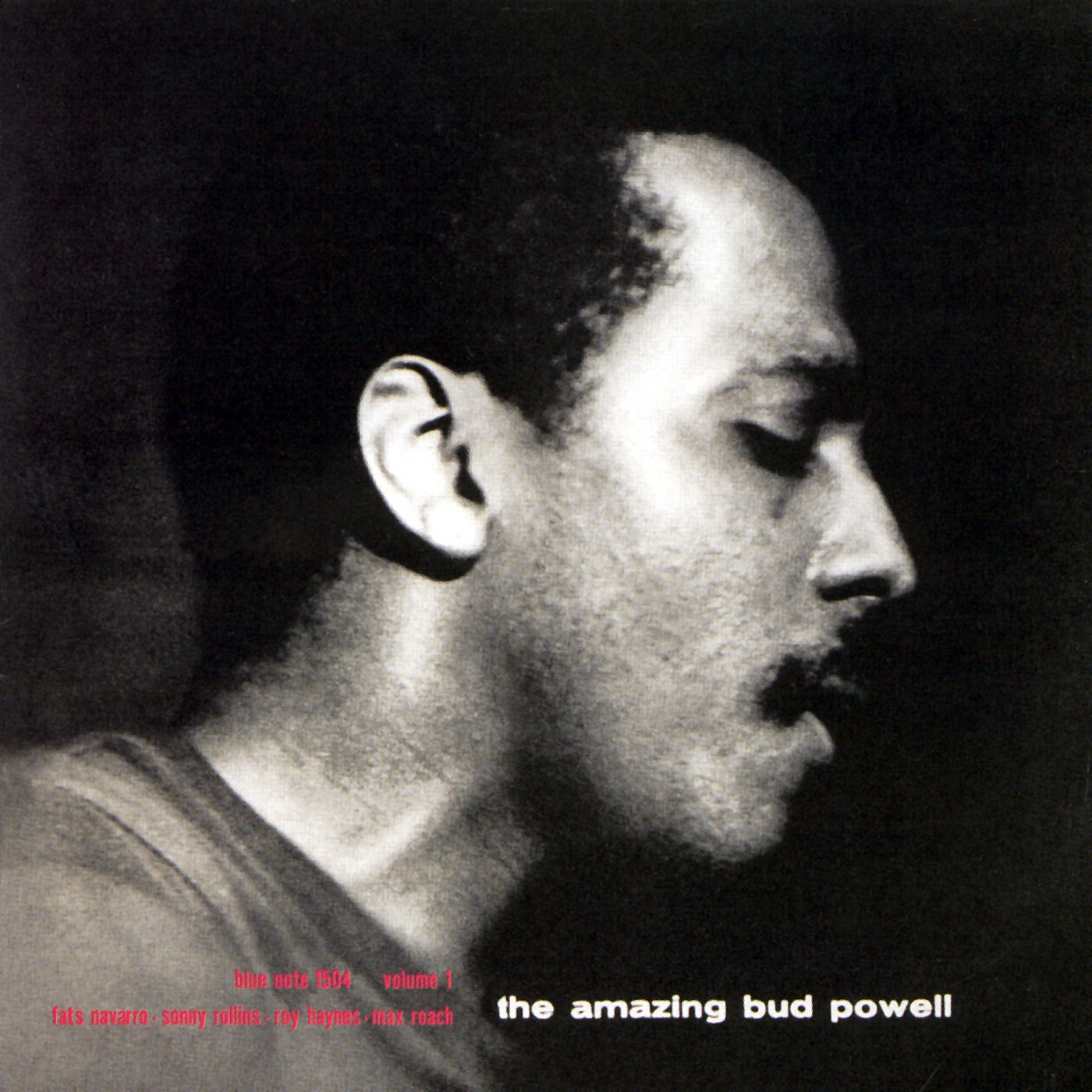

Bud Powell, The Amazing Bud Powell, Vol. 1

Powell revolutionized jazz piano through these sessions, translating Charlie Parker’s bebop innovations to the keyboard. “Un Poco Loco” demonstrates his left-hand rhythmic displacement techniques, while “Dance of the Infidels” showcases his lightning-fast right-hand runs and advanced harmonic concepts.

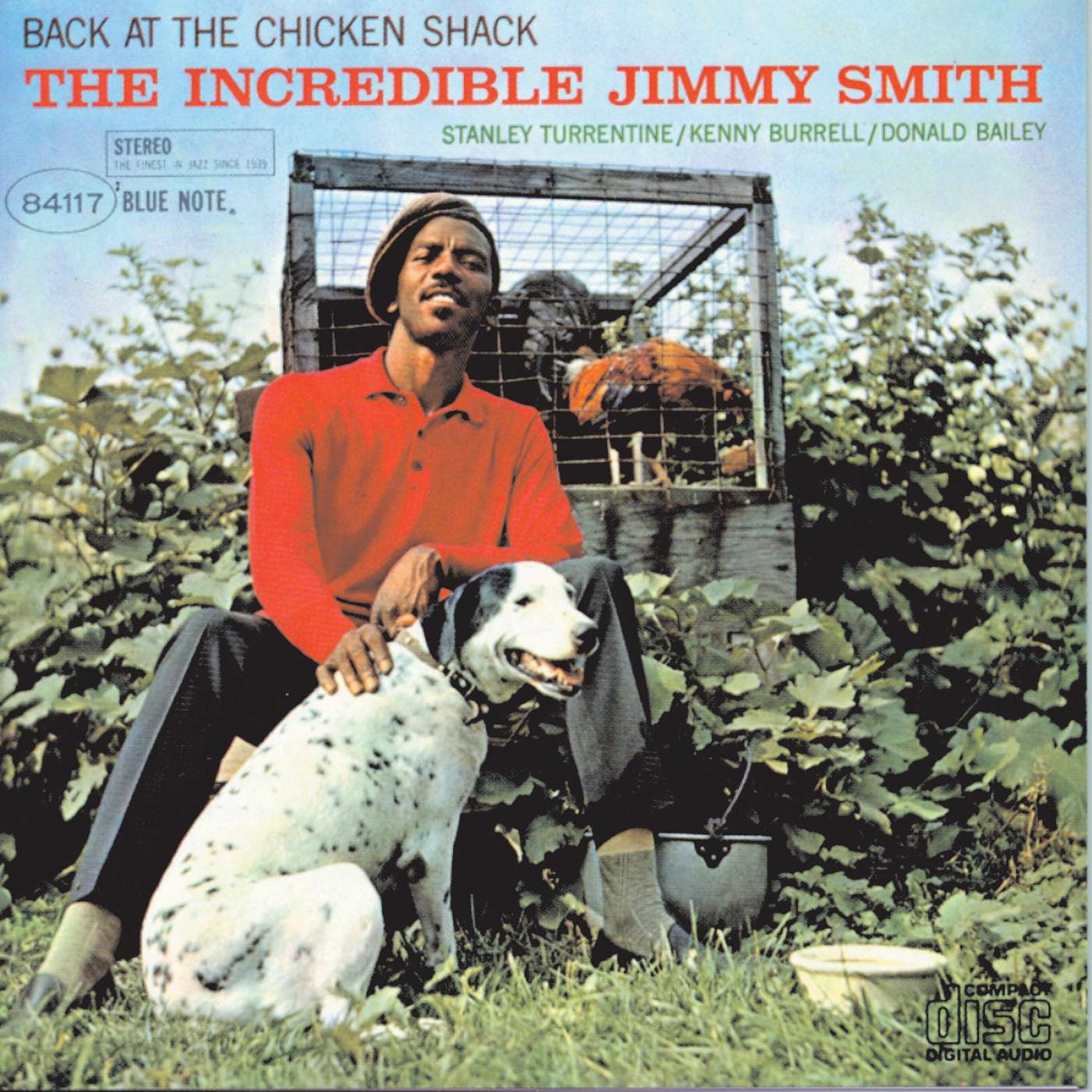

Jimmy Smith, Back at the Chicken Shack

Smith’s B3 organ technique redefined the instrument’s role in jazz. The title track’s walking bass lines played on the organ’s foot pedals, support Stanley Turrentine’s blues-drenched tenor. “Minor Chant” displays Smith’s mastery of gospel-influenced chord voicings.

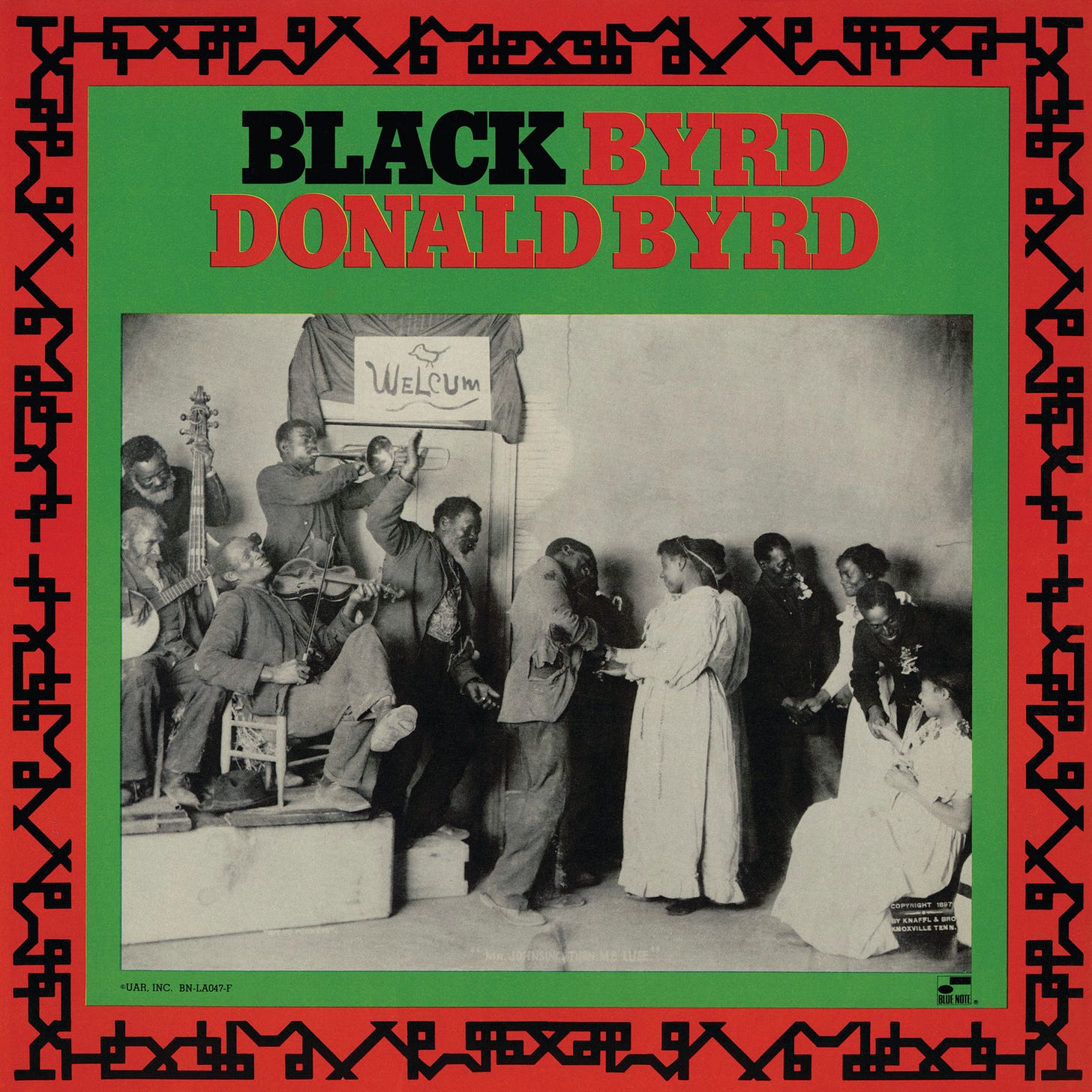

Donald Byrd, Black Byrd

Byrd used jazz concepts with R&B production techniques. “Flight Time” uses extended harmony within funk structures. The Mizell brothers’ production added electronic textures while maintaining instrumental sophistication.

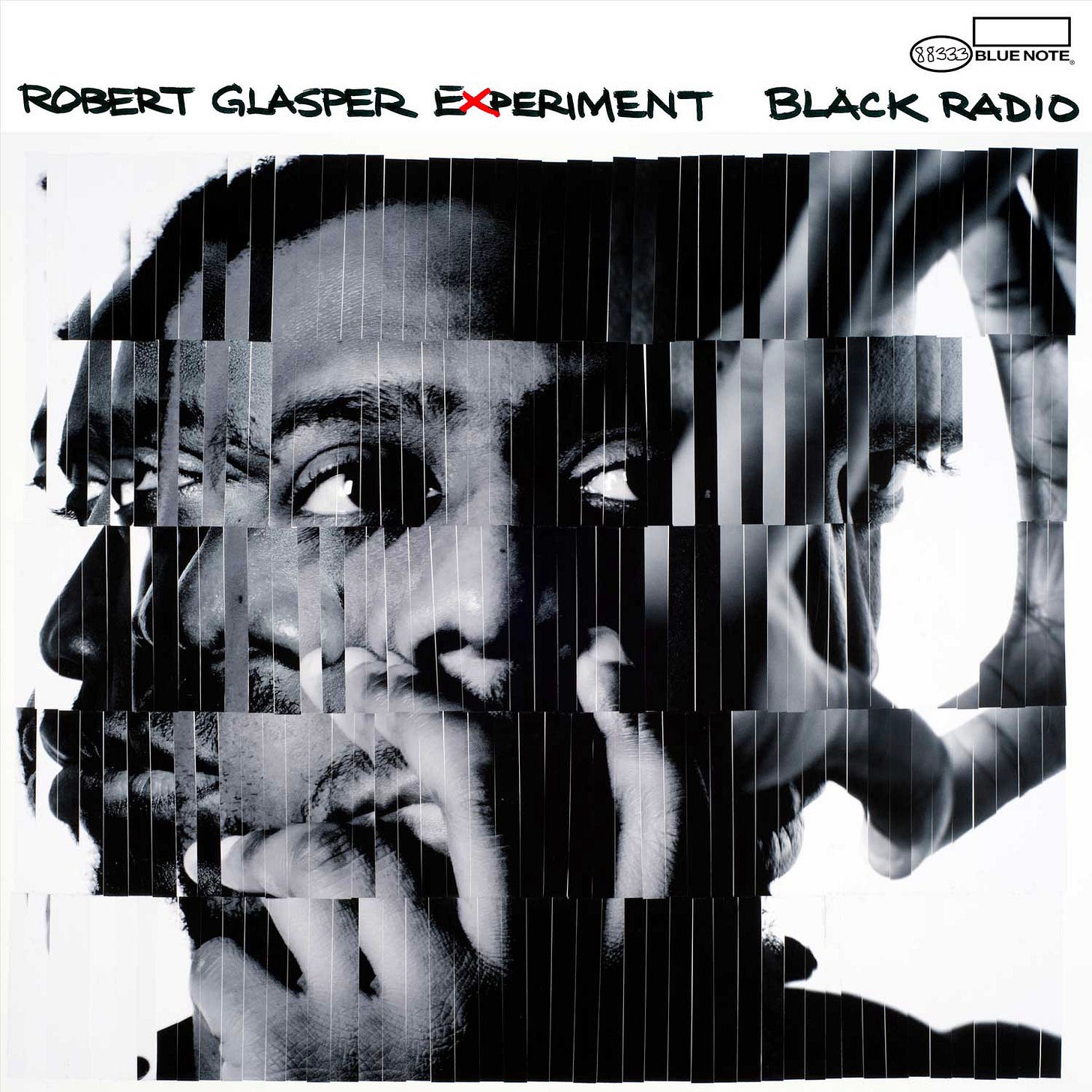

Robert Glasper Experiment, Black Radio

Glasper blends jazz harmony with hip-hop production values. “Afro Blue” reconstructs Mongo Santamaria’s composition through contemporary R&B sensibilities. The rhythm section adapts jazz improvisation to programmed beats without sacrificing spontaneity.

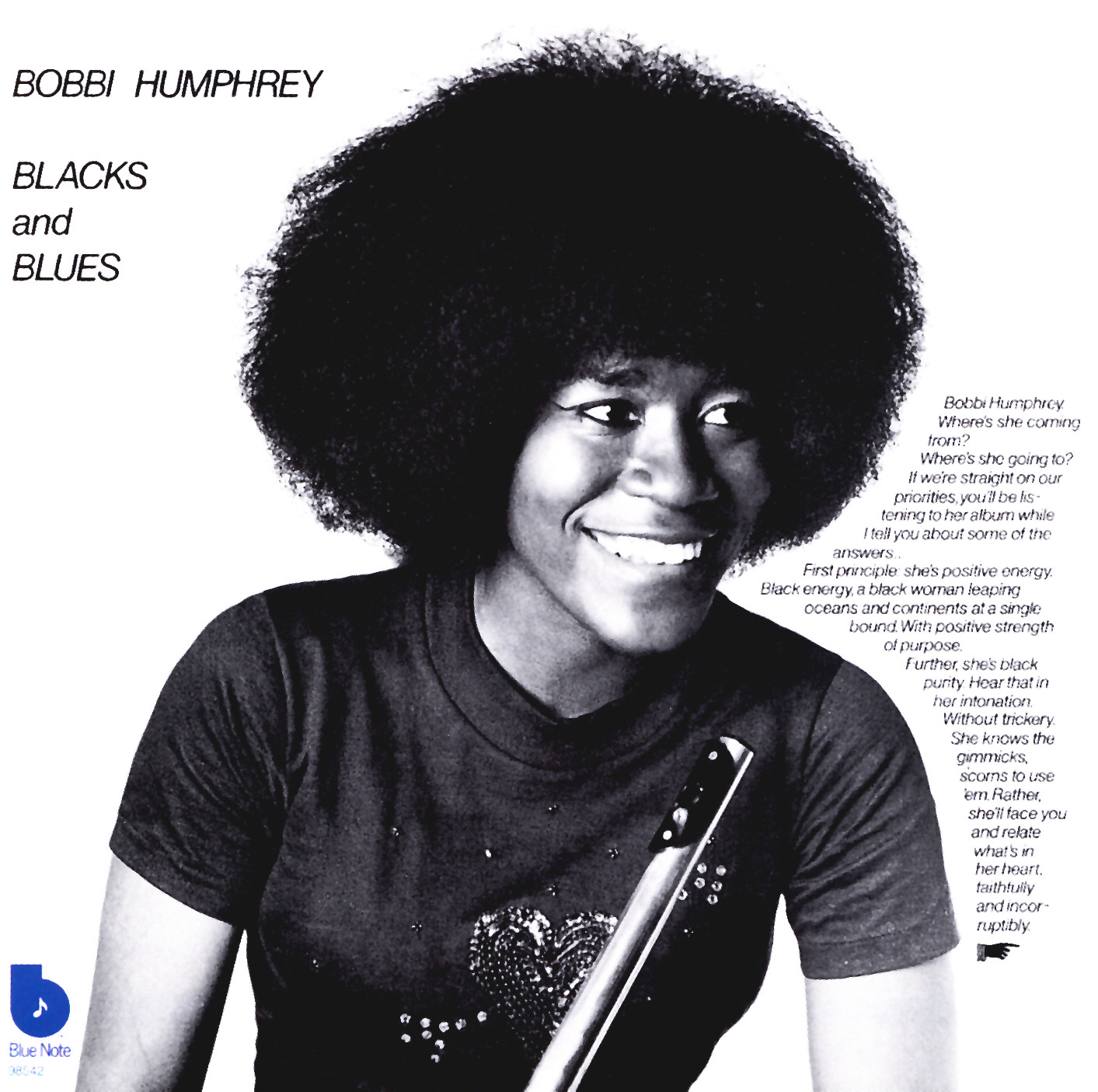

Bobbi Humphrey, Blacks and Blues

Humphrey revolutionized jazz flute through funk-based arrangements. “Chicago, Damn” showcases her blues-inflected melodic approach. The Mizell brothers’ production creates sophisticated R&B frameworks for her improvisation.

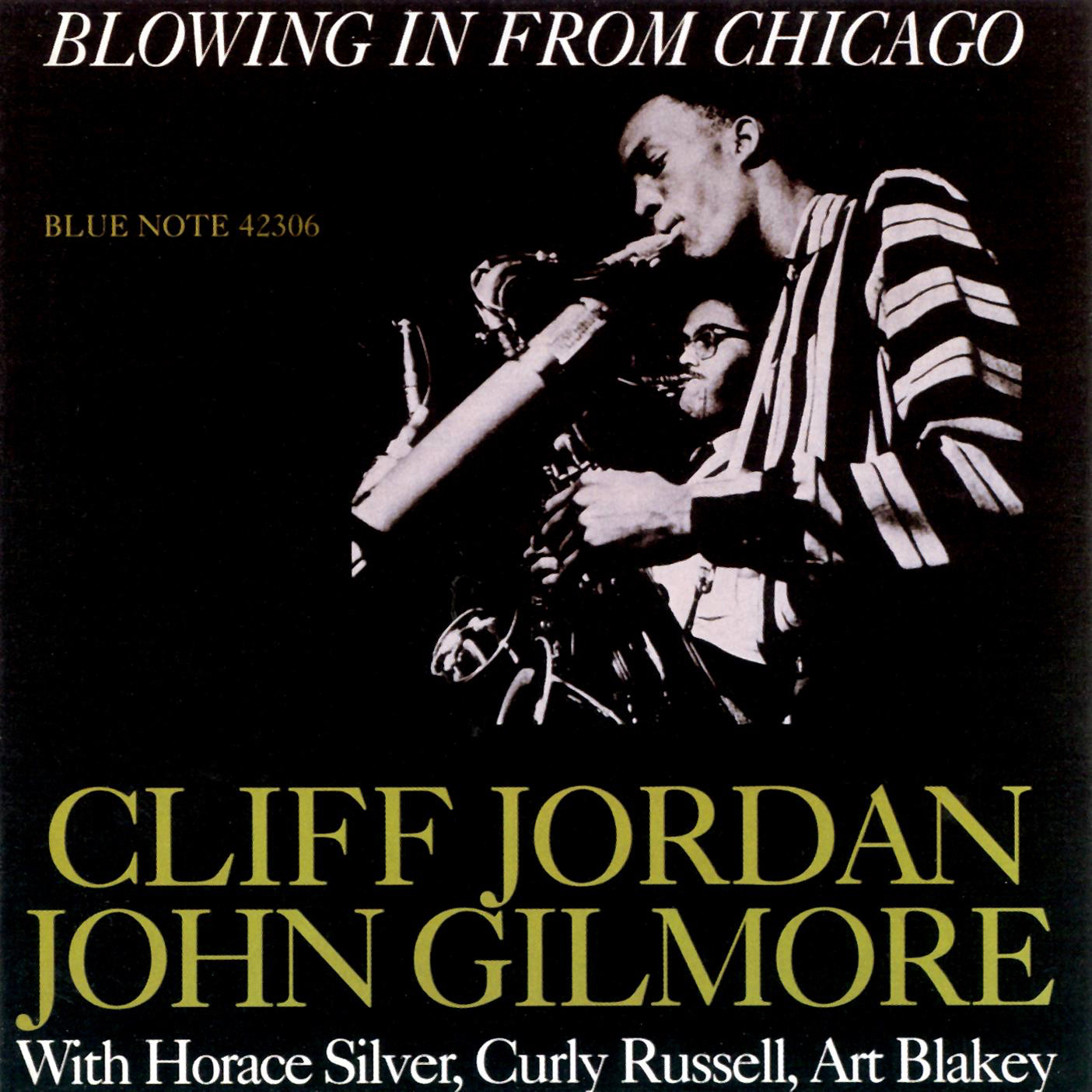

Clifford Jordan & John Gilmore, Blowing In from Chicago

This rare pairing of two tenor saxophonists from Chicago’s South Side produced remarkable results. Jordan’s fluid phrases contrast with Gilmore’s angular approach on “Status Quo.” Horace Silver’s piano accompaniment bridges the gap between hard bop and fledgling modal concepts.

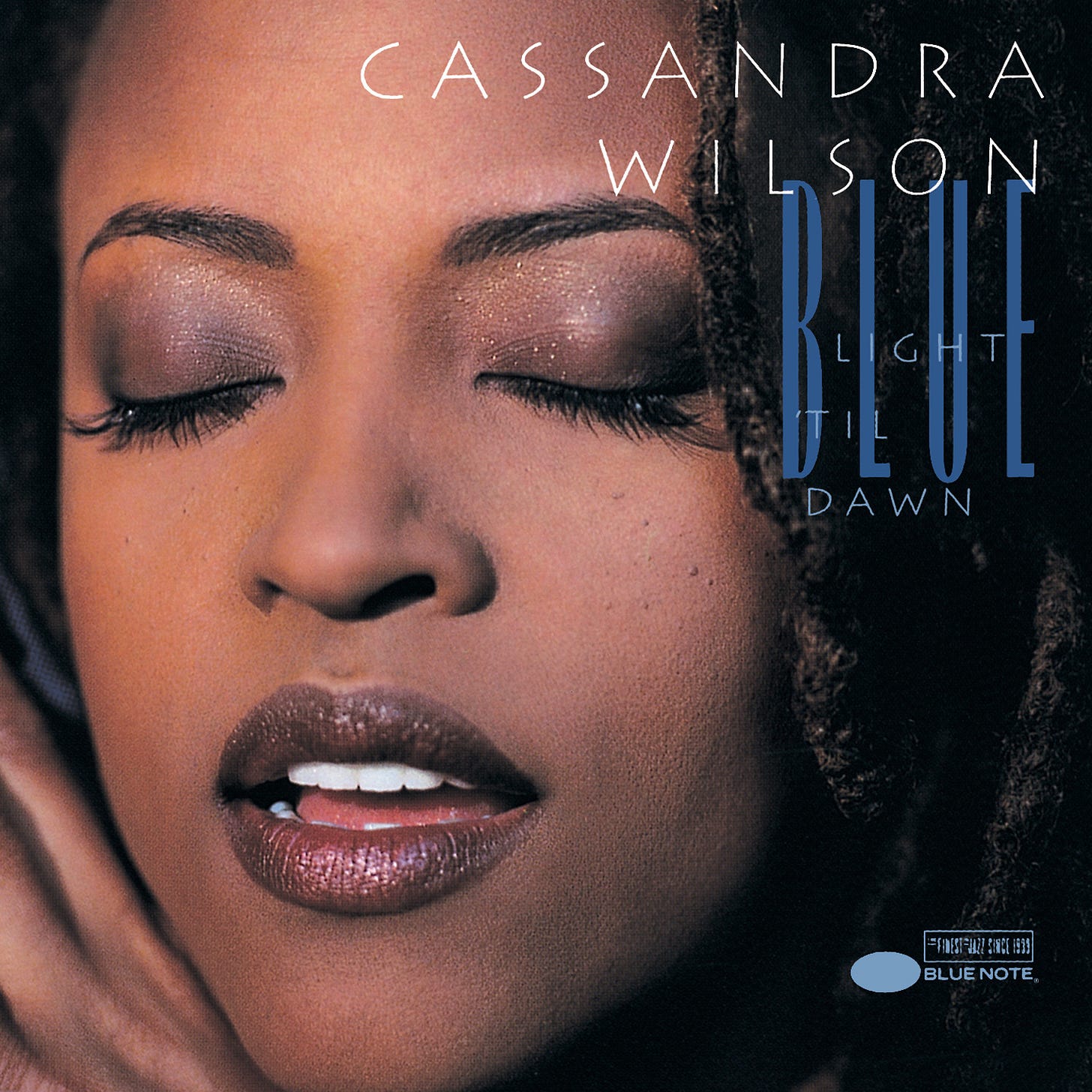

Cassandra Wilson, Blue Light ’Til Dawn

Wilson reconstructed the jazz vocal tradition through folk and blues filters. Her interpretation of “You Don’t Know What Love Is” strips away traditional jazz orchestration in favor of acoustic guitar and percussion. The sparse “Tell Me You’ll Wait for Me” arrangement creates unusual spatial dimensions.

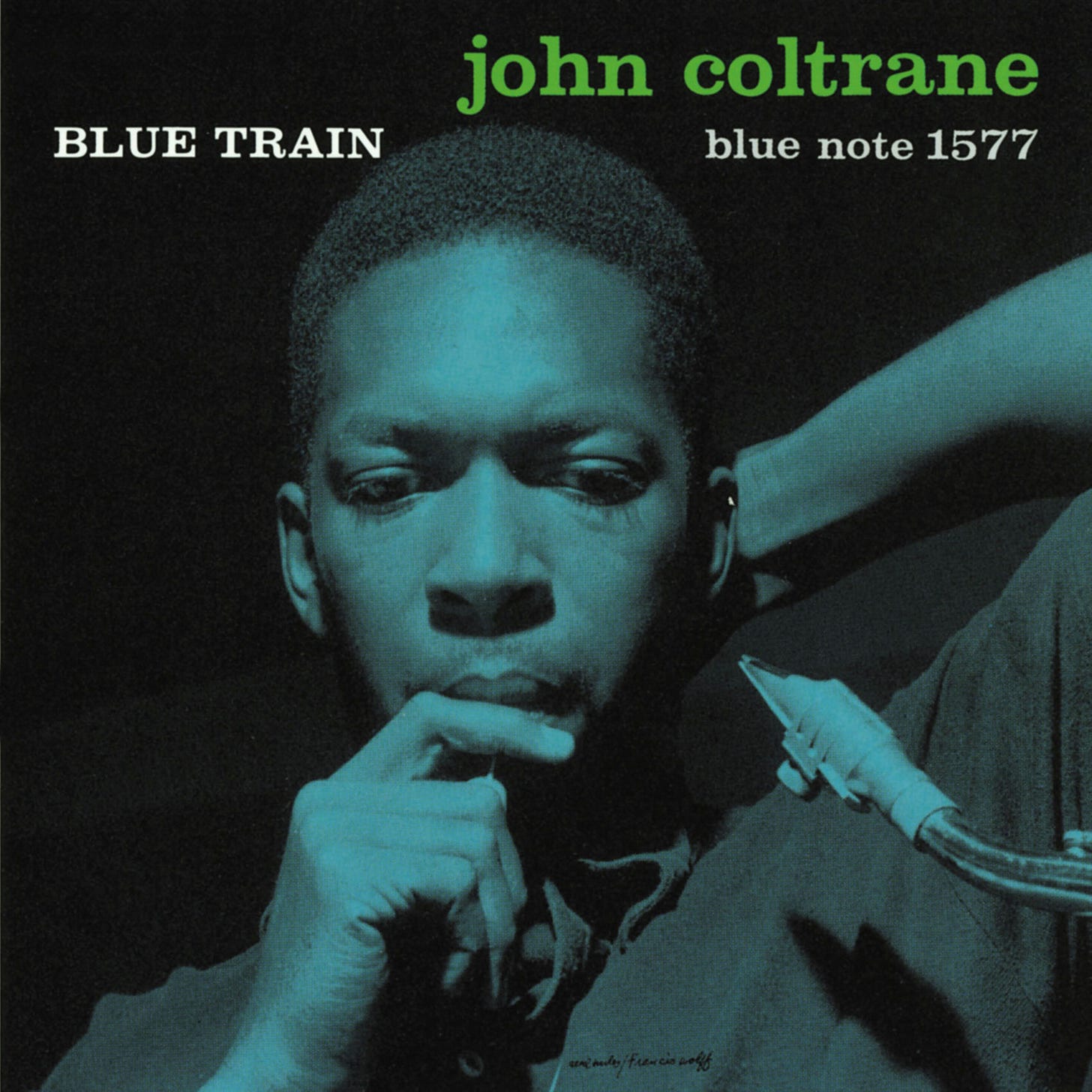

John Coltrane, Blue Train

Coltrane’s only Blue Note album as leader captured him at a crucial developmental stage. The title composition’s sophisticated chord progression and extended form pushed hard bop’s boundaries. Lee Morgan’s trumpet solos match Coltrane’s intensity, particularly on “Moment’s Notice,” where the 19-year-old trumpeter trades phrases with startling maturity.

Lou Donaldson, Blues Walk

Donaldson’s alto saxophone found the sweet spot between Charlie Parker’s complexity and Louis Jordan’s accessibility. The title track’s memorable melody became a jazz standard, while “Play Ray” pays tribute to Ray Charles with a gospel-tinged hard bop. Herman Foster’s piano work adds subtle harmonic depth beneath Donaldson’s bluesy lines.

Ike Quebec, Blues & Sentimental

Quebec’s tenor saxophone brought new dimensions to ballad interpretation. His breathy lower register and precise pitch control shine here. The quartet setting highlights Quebec’s connection to swing-era sensibilities while incorporating modern harmonic approaches.

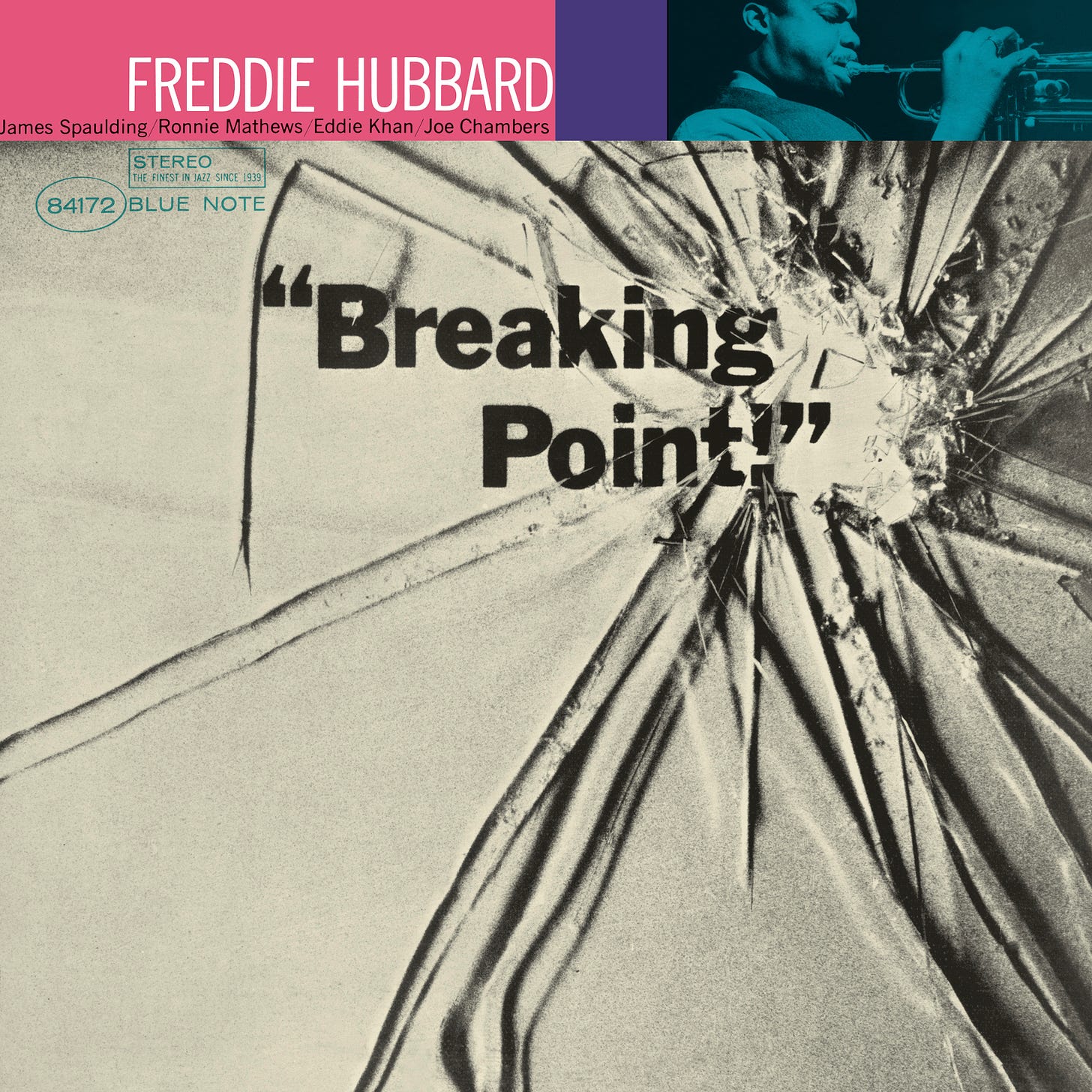

Freddie Hubbard, Breaking Point

Hubbard pushed hard bop’s boundaries through modal exploration. The title track’s shifting meters and extended form predicted jazz’s future directions. James Spaulding’s alto adds textural complexity to the trumpet-led ensemble.

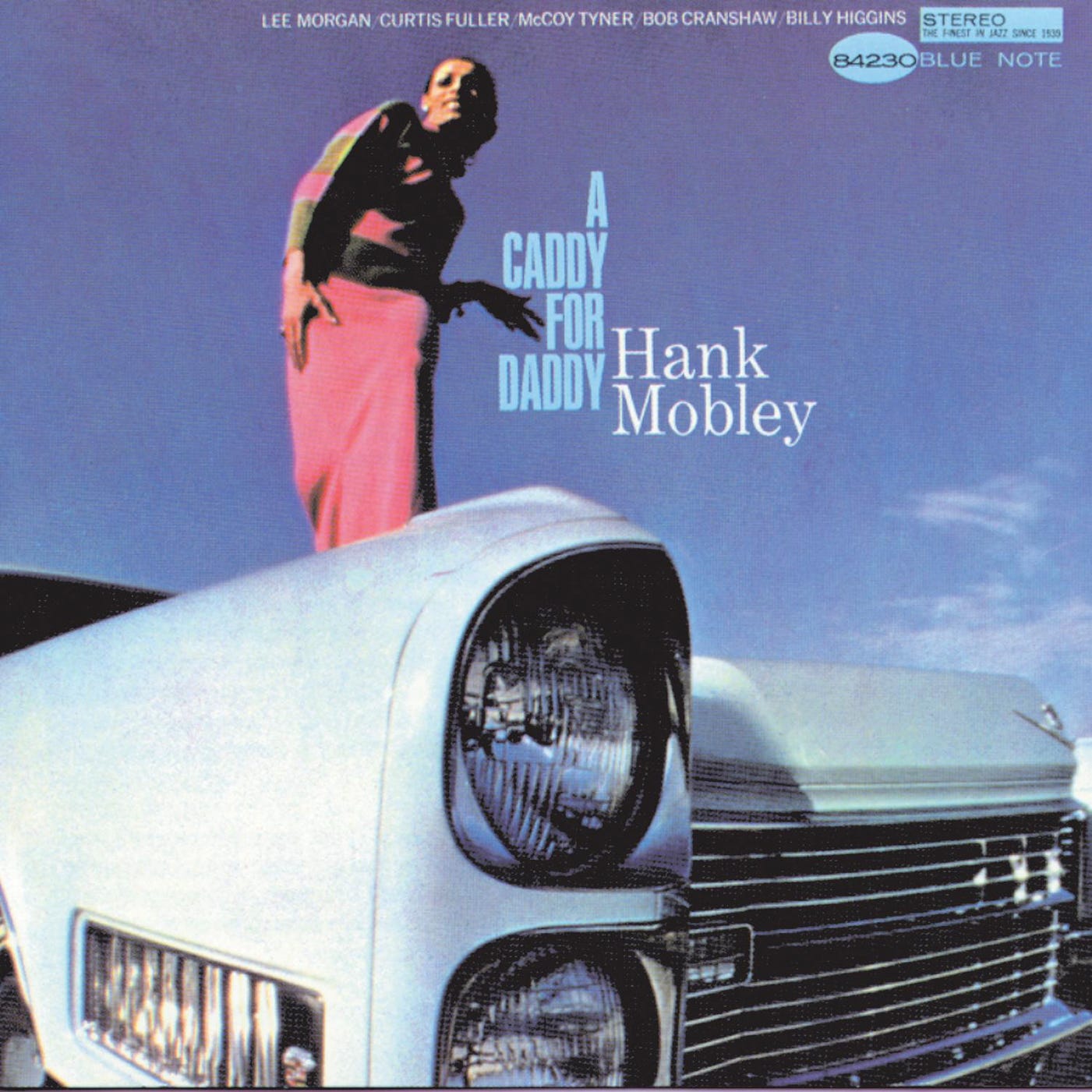

Hank Mobley, A Caddy for Daddy

Mobley’s quintet achieves the perfect balance between sophistication and swing. “Third Time Around” features his signature melodic development style, and Curtis Fuller’s trombone adds textural depth to the front-line arrangements.

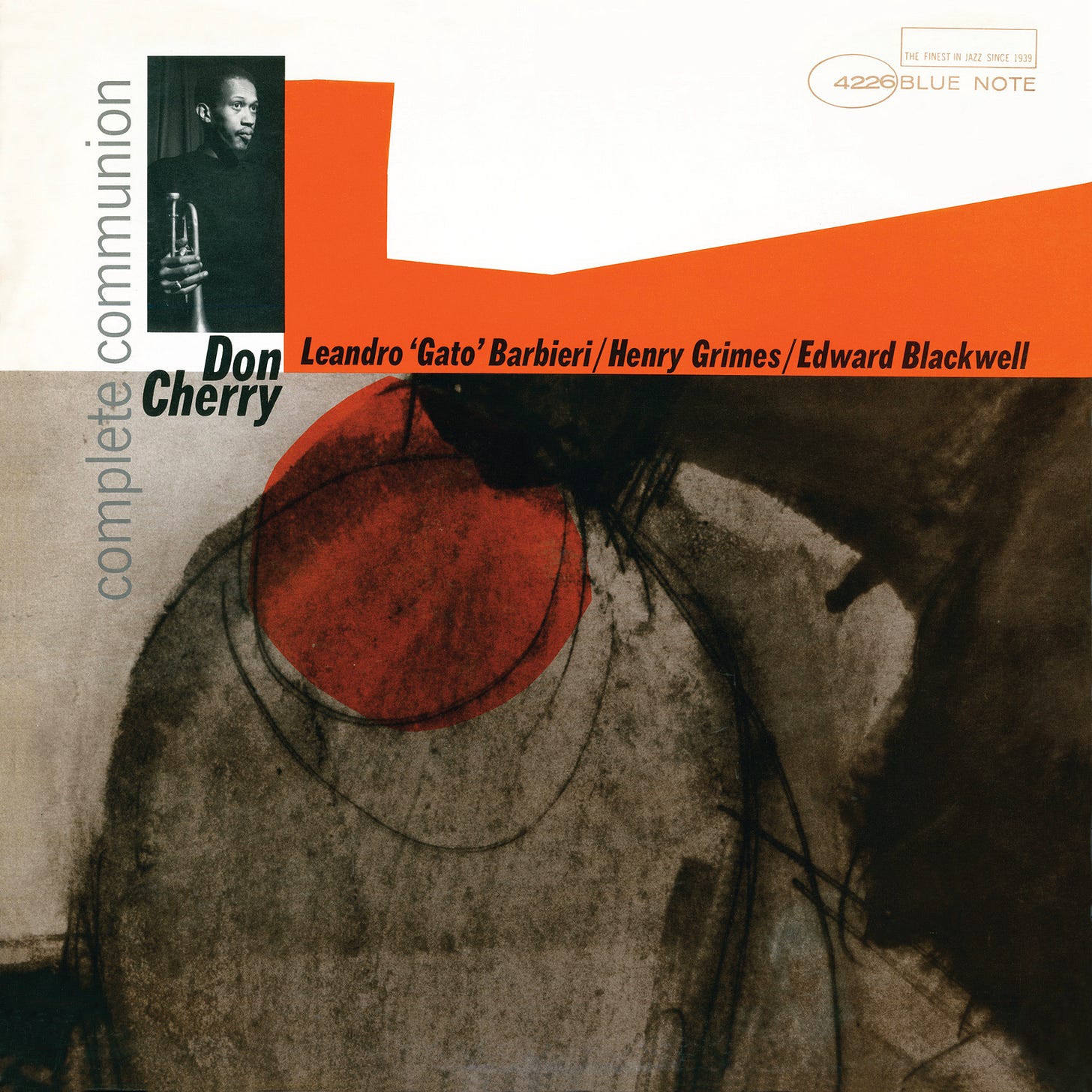

Don Cherry, Complete Communion

Cherry abandoned the traditional jazz structure for a continuous suite format. The album’s two extended pieces flow between composed themes and collective improvisation. Gato Barbieri’s tenor saxophone provides a passionate counterpoint to Cherry’s pocket trumpet phrases.

Bobby Hutcherson, Components

Hutcherson’s vibraphone adapts to structured composition and free improvisation. Side A presents his original compositions with conventional forms, while Side B explores Joe Chambers’ experimental pieces. “Movement” demonstrates Hutcherson’s innovative approach to texture and harmony.

Sam Rivers, Contours

Rivers brought his advanced harmonic concepts and extended techniques to this challenging session. “Point of Many Returns” abandons fixed chord changes for spontaneous group interaction. Herbie Hancock’s piano provides structural reference points within the free-flowing improvisations.

Jimmy Smith, Cool Blues

Smith strips down to a trio format, highlighting his revolutionary organ technique. “Cool Blues” showcases his ability to maintain walking bass lines while executing complex right-hand runs. The album documents Smith’s transformation of blues language through jazz harmony.

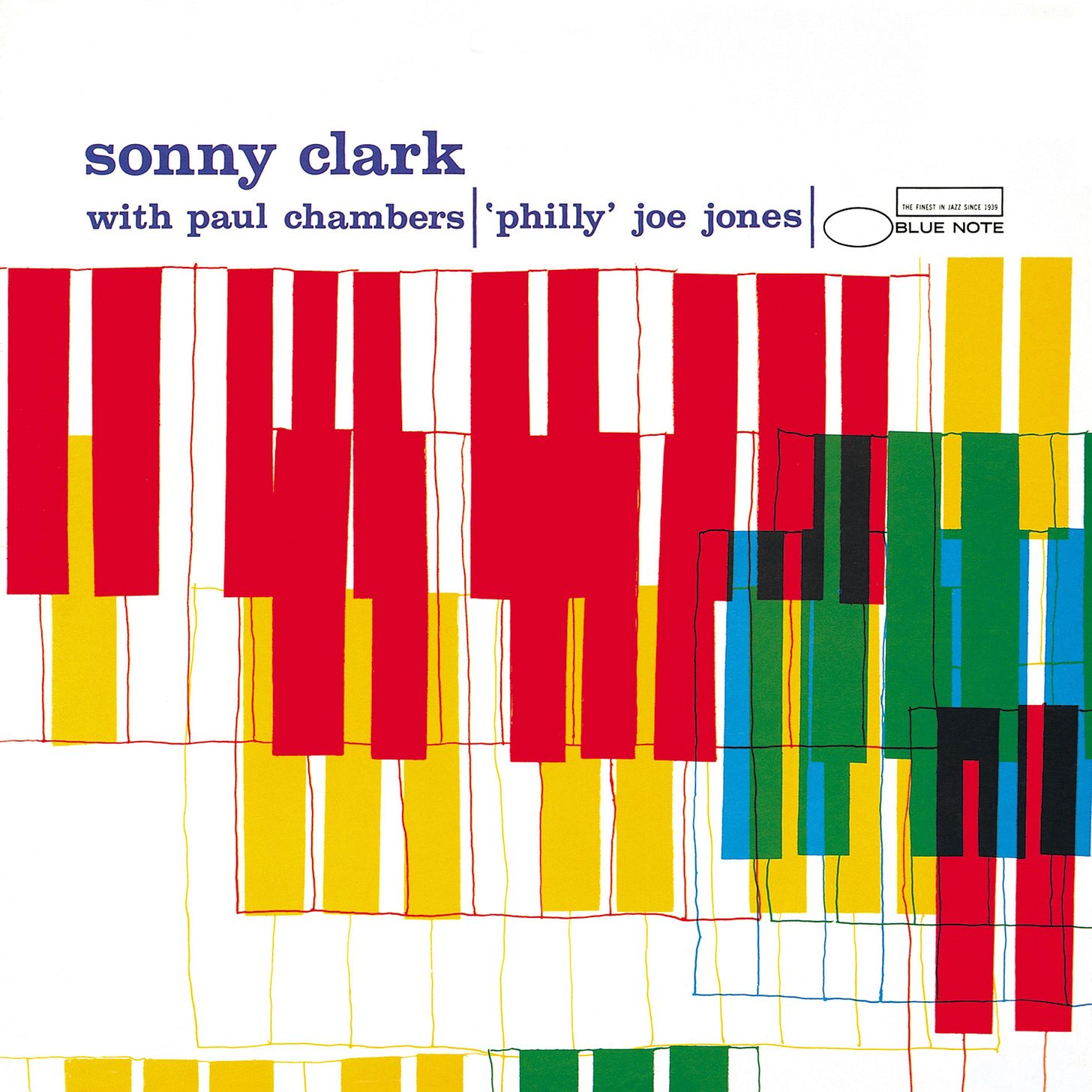

Sonny Clark, Cool Struttin’

Clark’s masterpiece balanced intellectual complexity with the gut-level swing. The title track’s walking bass line and relaxed tempo mask intricate harmonic substitutions. “Blue Minor” exhibits Clark’s ability to construct logical solos while maintaining emotional intensity.

Lee Morgan, Cornbread

Morgan balanced sophisticated composition with blues authenticity. The title track’s memorable hook anchors advanced harmonic movement. Herbie Hancock’s piano comping adds subtle rhythmic displacement beneath Morgan’s assertive trumpet lines.

Jackie McLean, Destination…Out!

McLean merged his bebop roots with free jazz concepts in this forward-thinking session. “Love and Hate” pairs angular melodies with shifting time signatures. Grachan Moncur III’s compositions push McLean’s alto into unexplored harmonic territory while maintaining rhythmic momentum.

Bobby Hutcherson, Dialogue

The unusual front line of vibraphone and alto saxophone creates distinctive textures. Andrew Hill’s compositions challenge conventional harmony while maintaining melodic focus. “Les Noirs Marchant” reflects the era’s civil rights struggles through abstract musical metaphor.

Hank Mobley, Dippin’

Mobley’s tenor sound bridges hard bop intensity and soul jazz accessibility. “The Dip” introduces a shuffling groove that anticipates funk developments. Lee Morgan’s trumpet provides a bright counterpoint to Mobley’s middle-register warmth.

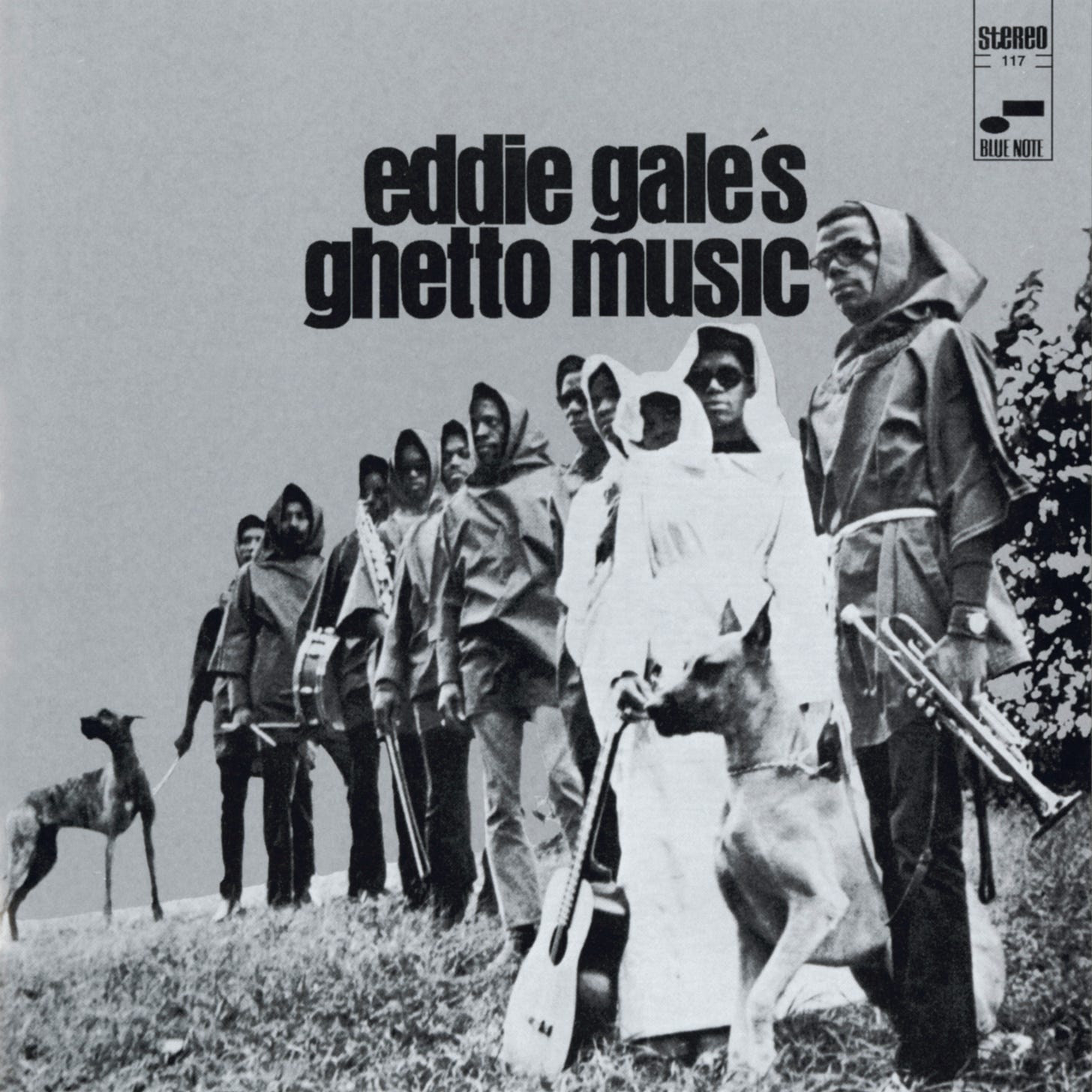

Eddie Gale, Eddie Gale’s Ghetto Music

Gale mixed avant-garde jazz with African-American church music. The eleven-voice choir adds spiritual depth to modal jazz structures. “The Rain” combines free improvisation with gospel-influenced melody.

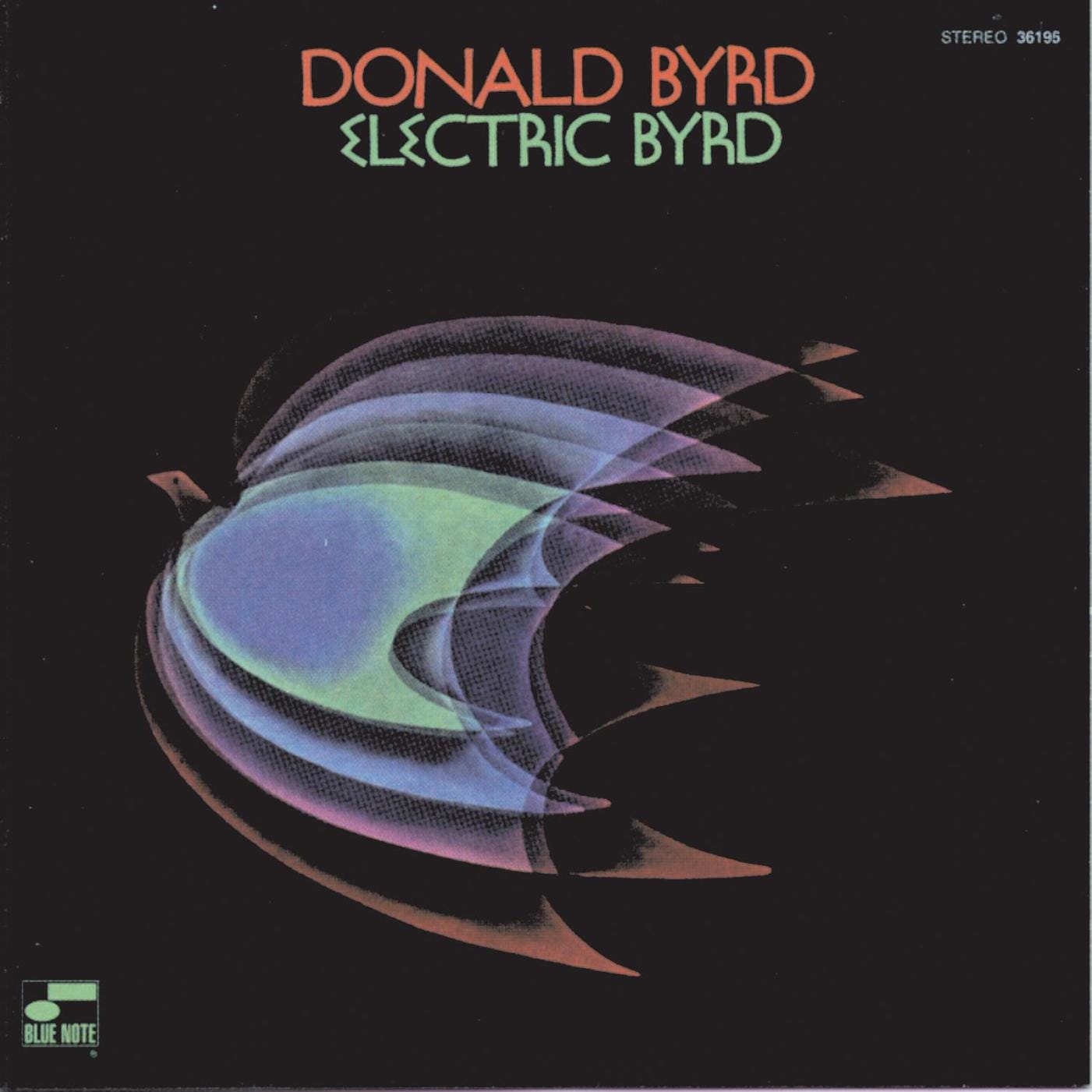

Donald Byrd, Electric Byrd

Byrd explored electronic textures while maintaining improvisational integrity. “Estavanico” uses echo effects and electric piano to create atmospheric backgrounds. The rhythm section combines jazz flexibility with rock intensity.

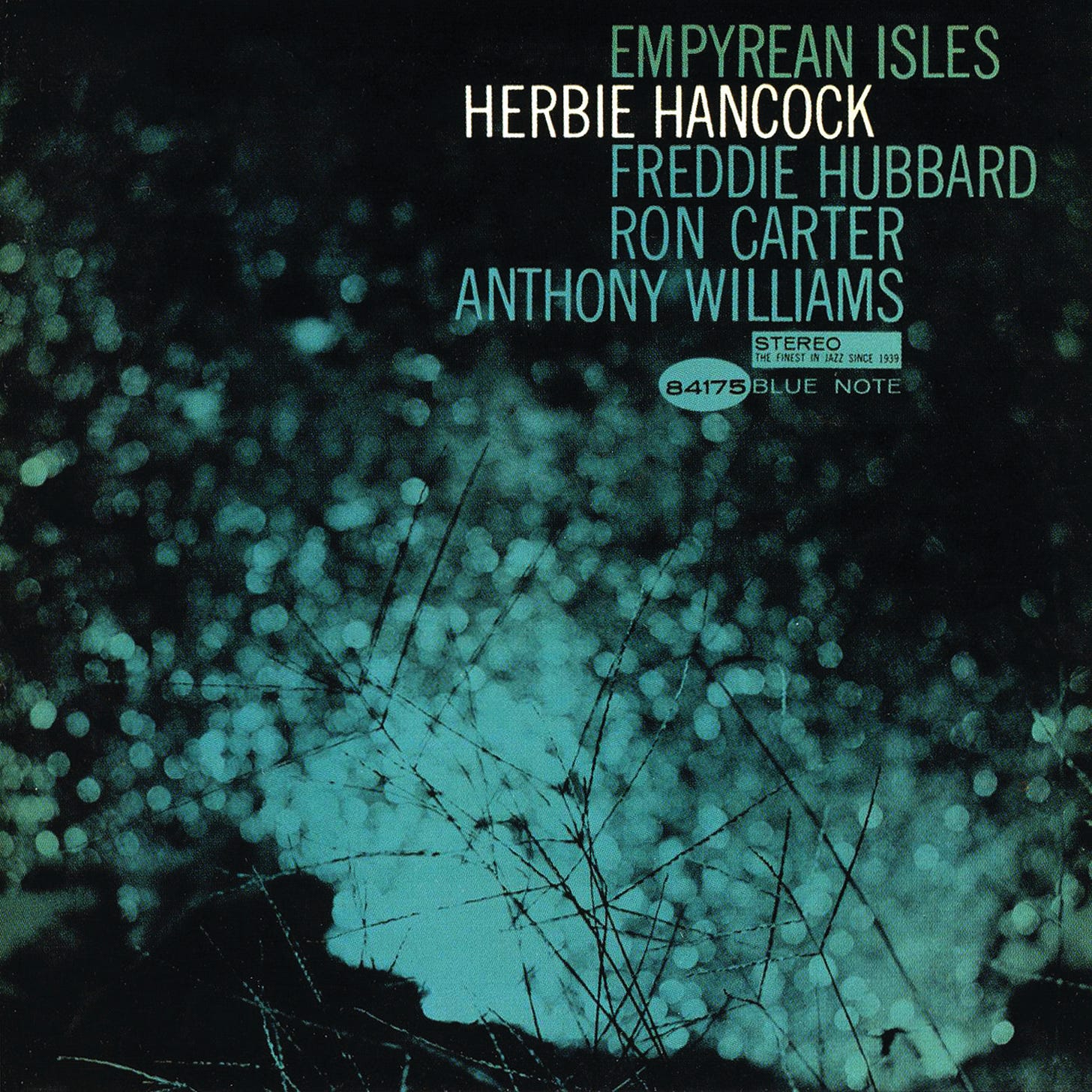

Herbie Hancock, Empyrean Isles

Hancock’s quartet created new textural possibilities without electronic instruments. “Cantaloupe Island” pairs modal harmony with rhythmic innovation. Freddie Hubbard’s cornet fills the space typically occupied by saxophone, allowing unusual harmonic freedom.

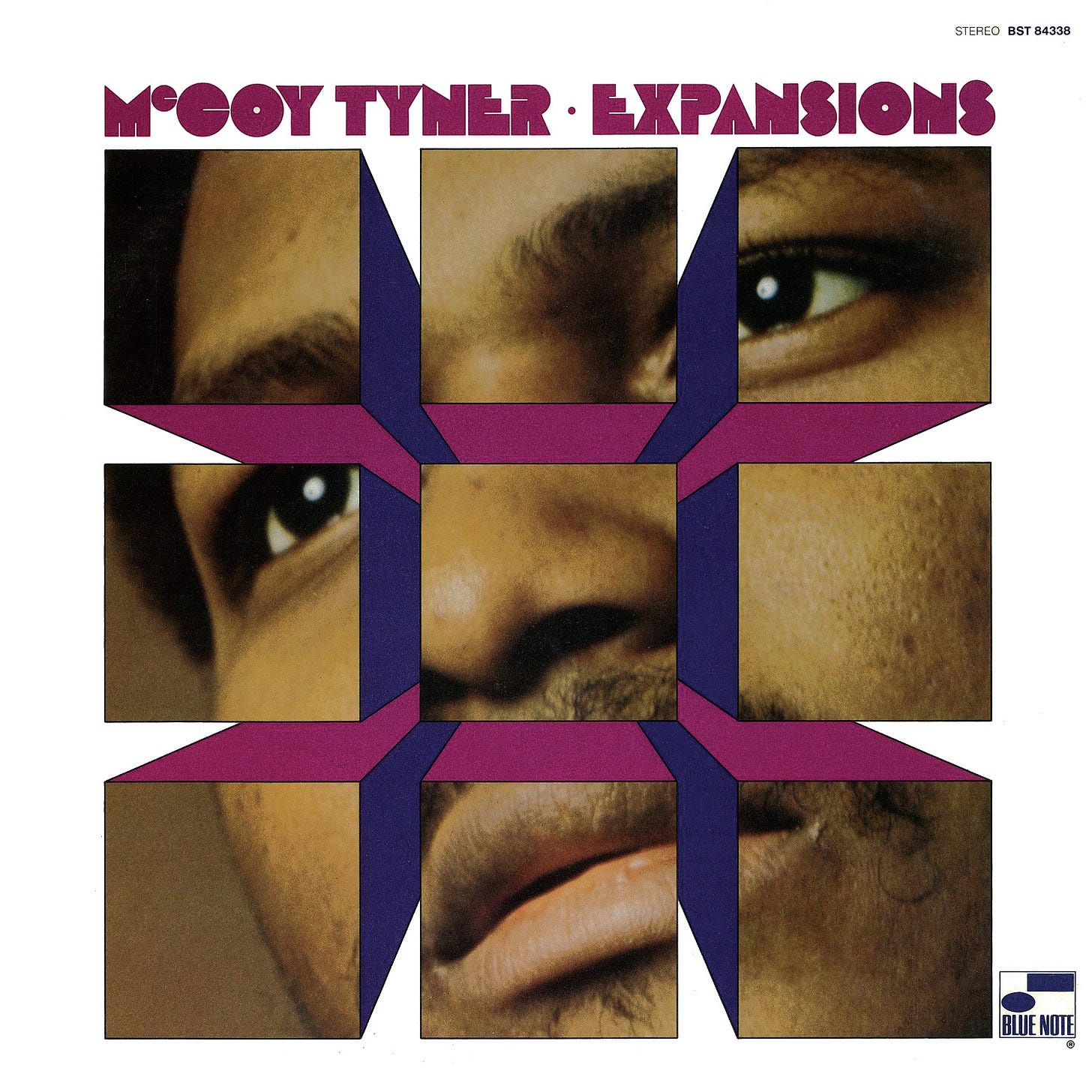

McCoy Tyner, Expansions

Tyner expanded his quartet with woodwinds and percussion. “Vision” demonstrates his advanced modal harmony approach. Gary Bartz’s alto and Wayne Shorter’s tenor create complex textural layers above Tyner’s powerful piano work.

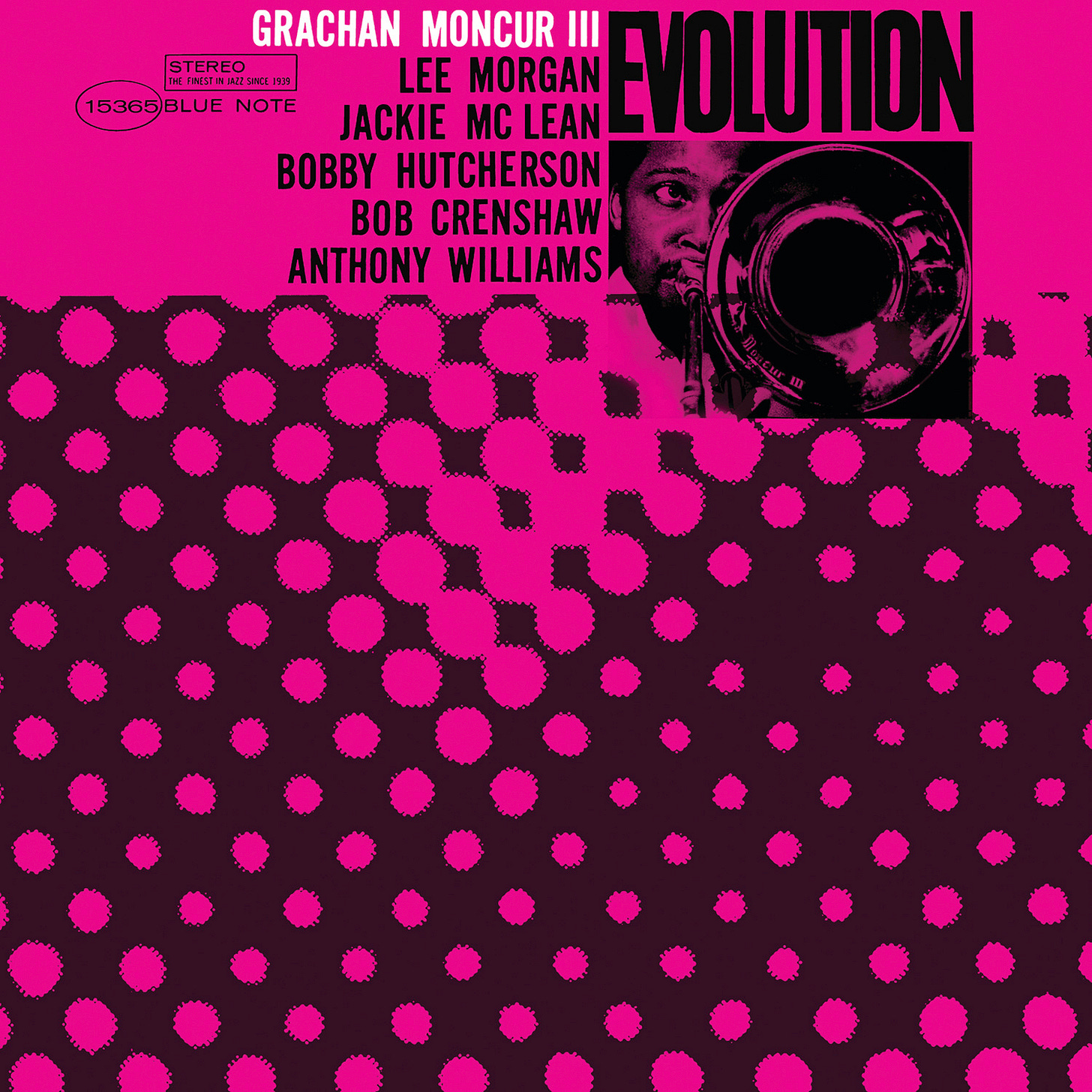

Grachan Moncur III, Evolution

Moncur’s debut as leader redefined modern jazz composition. “Air Raid” creates tension through sparse arrangements and strategic silence. The title track combines elements of blues, free jazz, and contemporary classical music into a coherent personal statement.

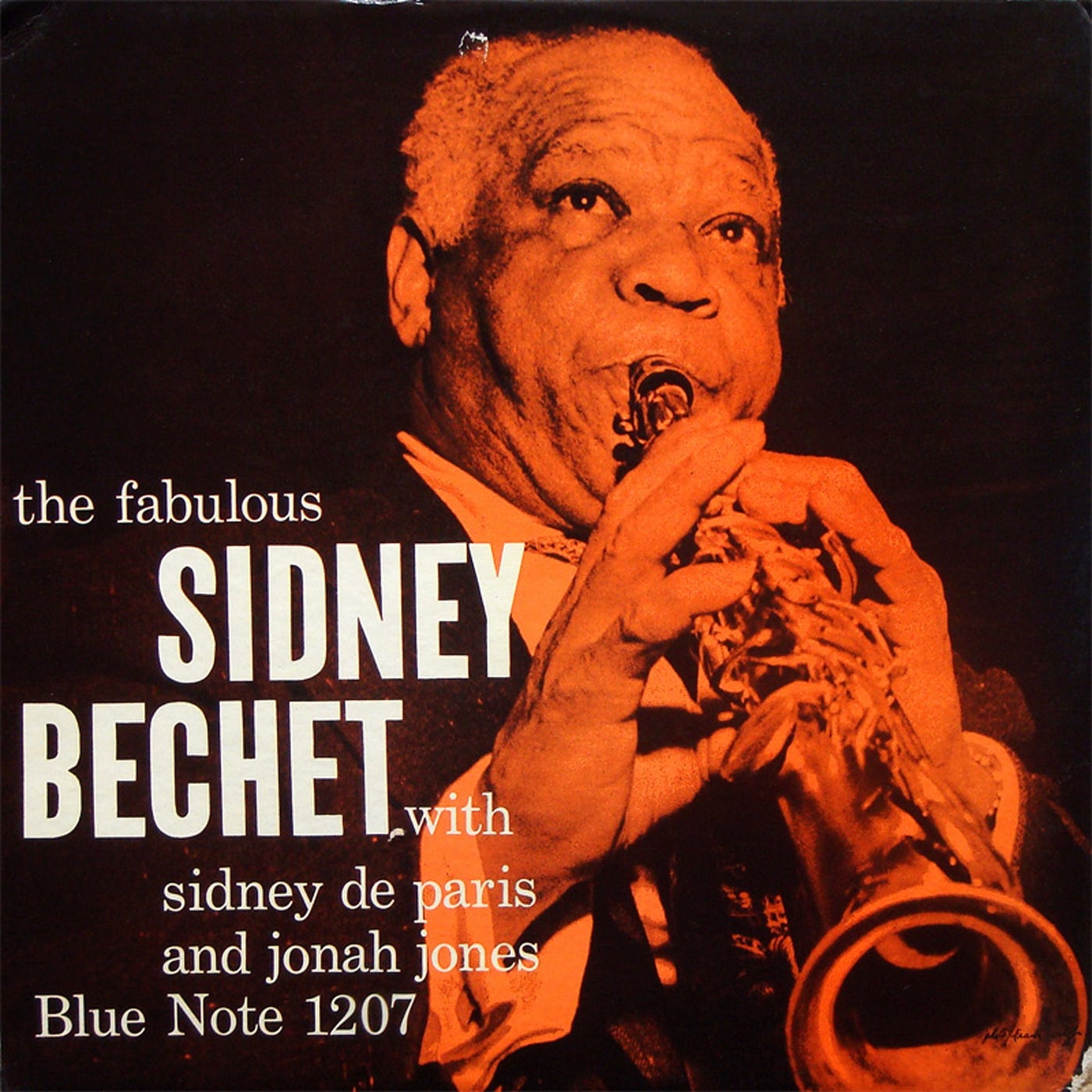

Sidney Bechet, The Fabulous Sidney Bechet

New Orleans clarinet master Sidney Bechet brought authenticity and fire to these early Blue Note sessions. His soprano saxophone work demonstrates his pioneering approach to the instrument. The recordings preserve traditional jazz with forward-thinking production values, establishing Blue Note’s commitment to sonic excellence.

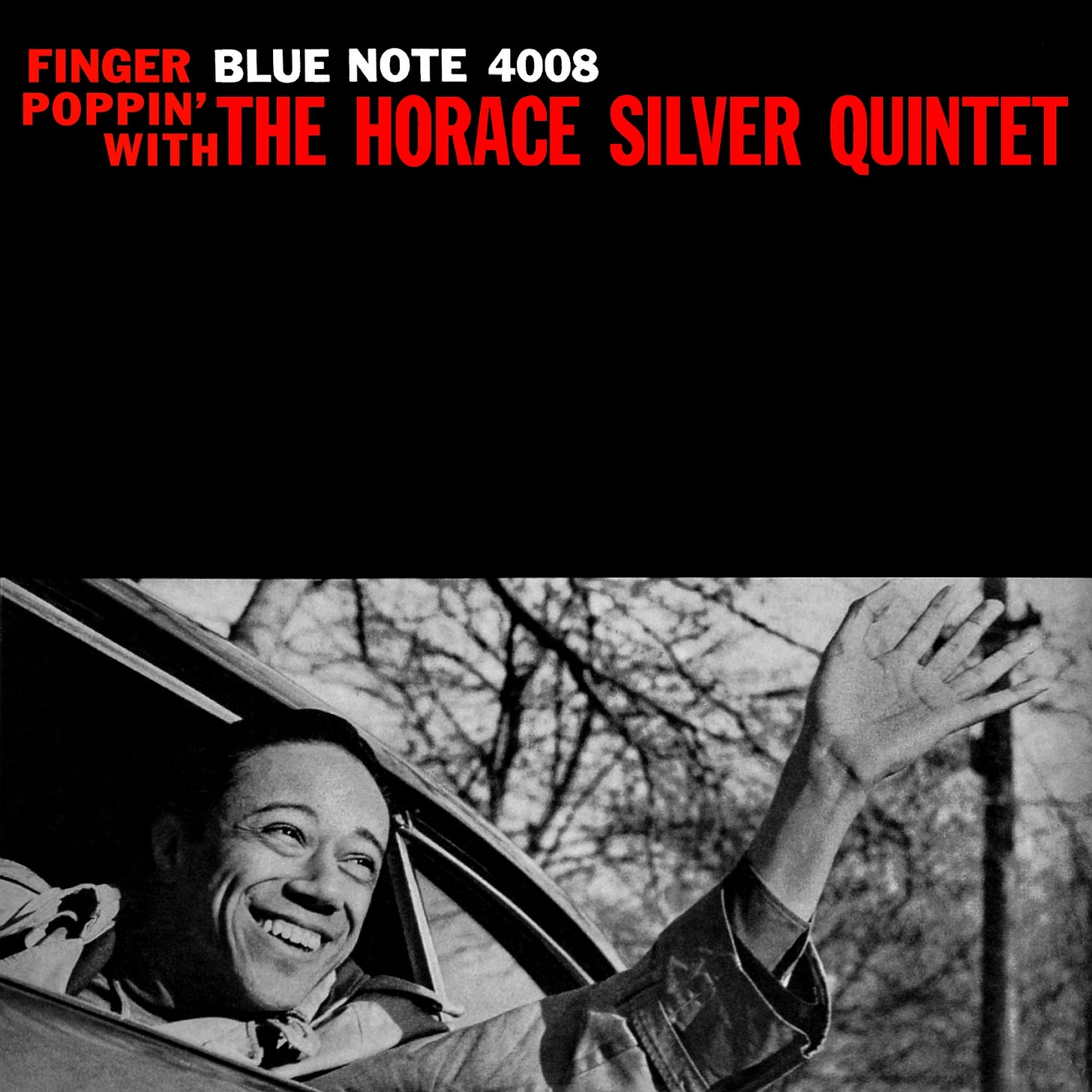

The Horace Silver Quintet, Finger Poppin’ With the Horace Silver Quintet

Silver’s quintet crafted a blueprint for soul jazz on this recording. “Juicy Lucy” pairs blues-based melodies with sophisticated harmonies, while “Sweet Stuff” demonstrates Silver’s gift for memorable compositions. The rhythm section’s precise interaction established new standards for ensemble playing.

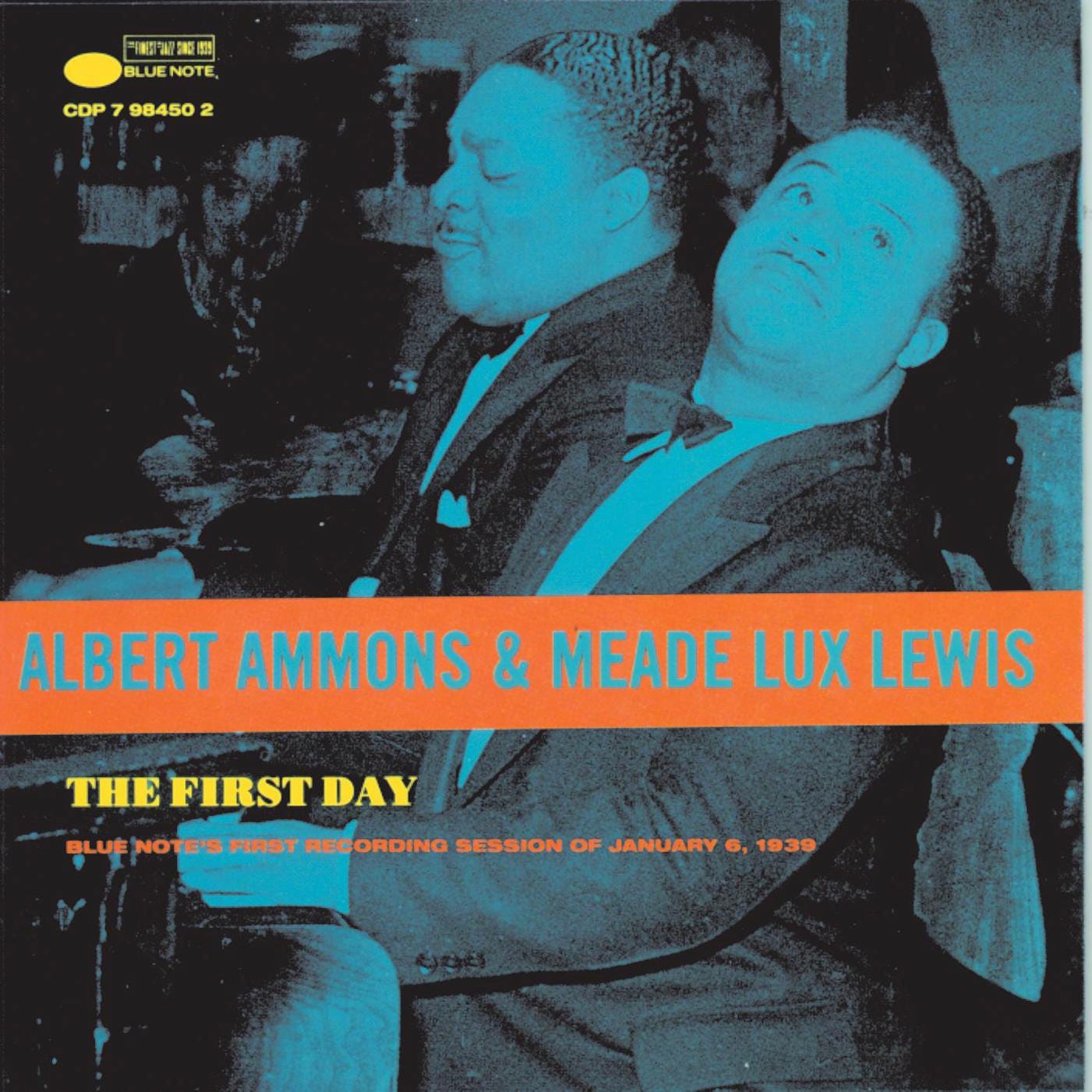

Albert Ammons & Meade Lux Lewis, The First Day

Boogie-woogie piano pioneer Albert Ammons launched Blue Note’s recording history. His muscular left hand and rolling rhythms influenced generations of blues and jazz pianists. “Boogie Woogie Stomp” displays his technical mastery and rhythmic drive.

Alphonse Mouzon, Funky Snakefoot

Mouzon merged jazz fusion with funk grooves. The title track demonstrates his ability to maintain complexity within dance-oriented grooves. Electric piano and synthesizer textures update Blue Note’s sound while preserving improvisational values.

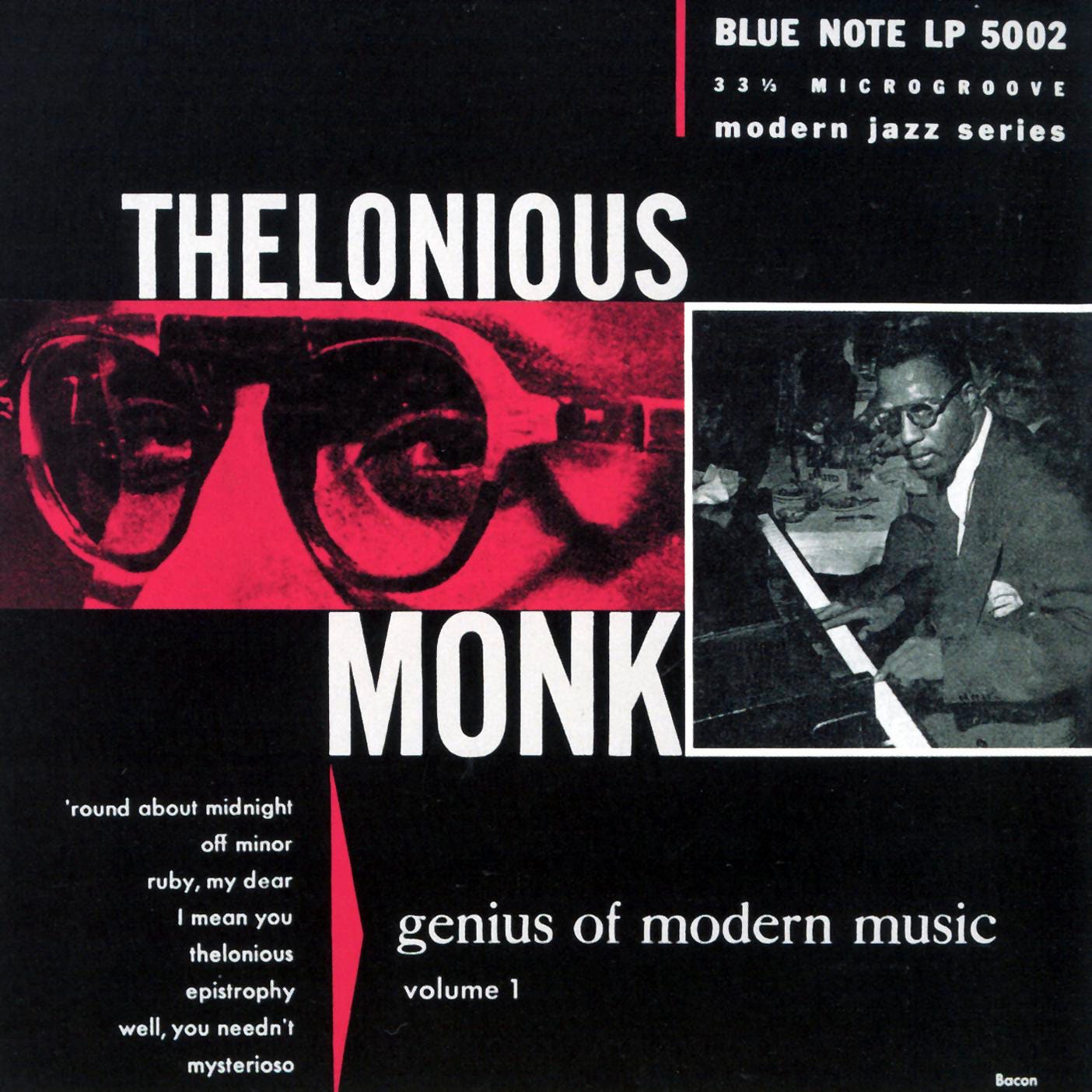

Thelonious Monk, Genius of Modern Music Vol. 1 & Vol. 2

These foundational recordings introduced Monk’s revolutionary harmonic concepts and compositional brilliance. “Ruby, My Dear” showcases his unique voicings and angular melodic approach. The sessions documented bebop’s development while pointing toward future innovations.

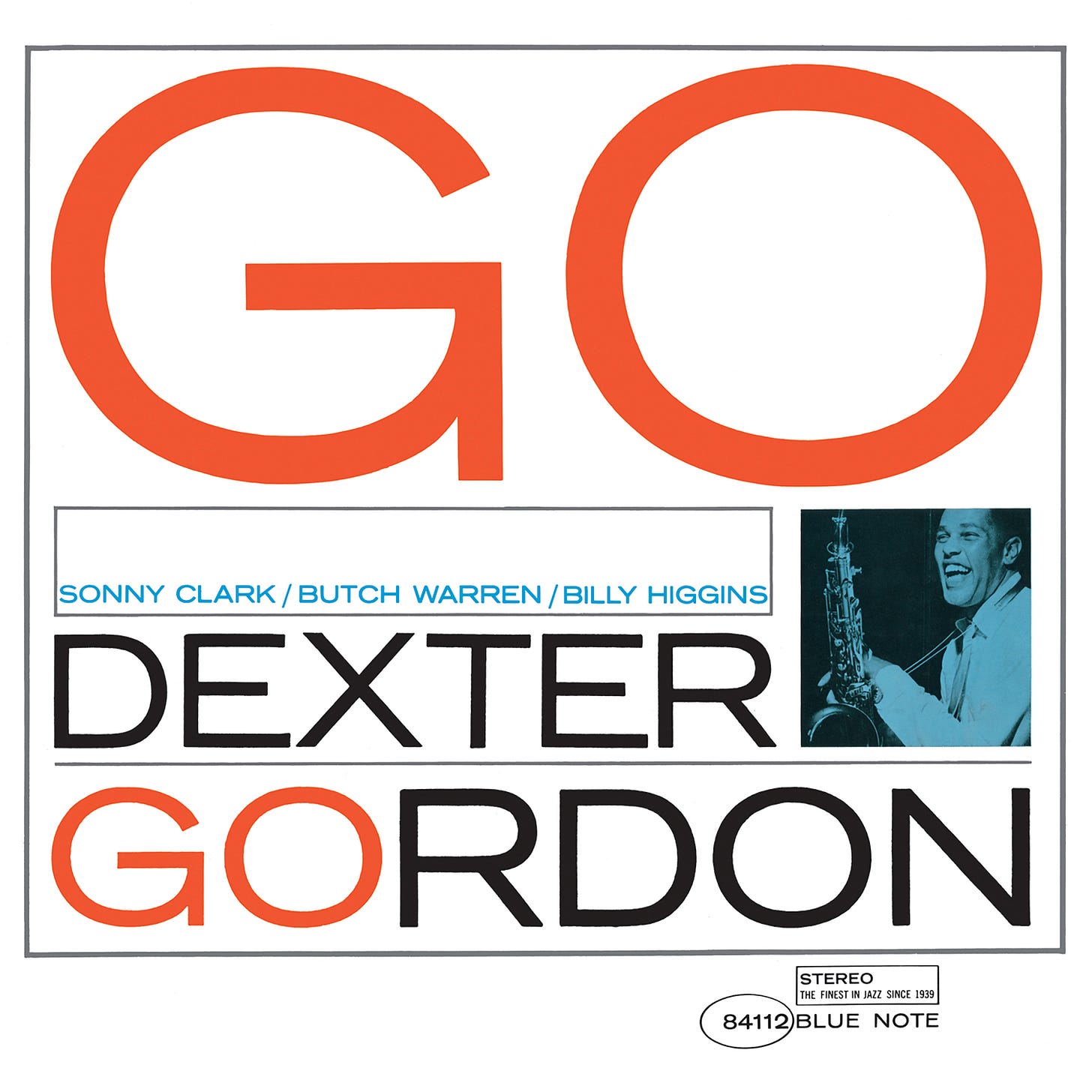

Dexter Gordon, Go

Gordon’s first Blue Note album as leader captures his mature style at its peak. His solo on “Three O’Clock in the Morning” demonstrates his mastery of timing and space. The rhythm section, featuring Sonny Clark’s piano, supports Gordon’s behind-the-beat phrasing.

Grant Green, Grant’s First Stand

Green’s debut as leader showcases his linear, horn-like approach to guitar. “Miss Ann’s Tempo” pairs his single-note lines with Baby Face Willette’s organ chords. The trio format allows Green’s distinctive phrasing to shine.

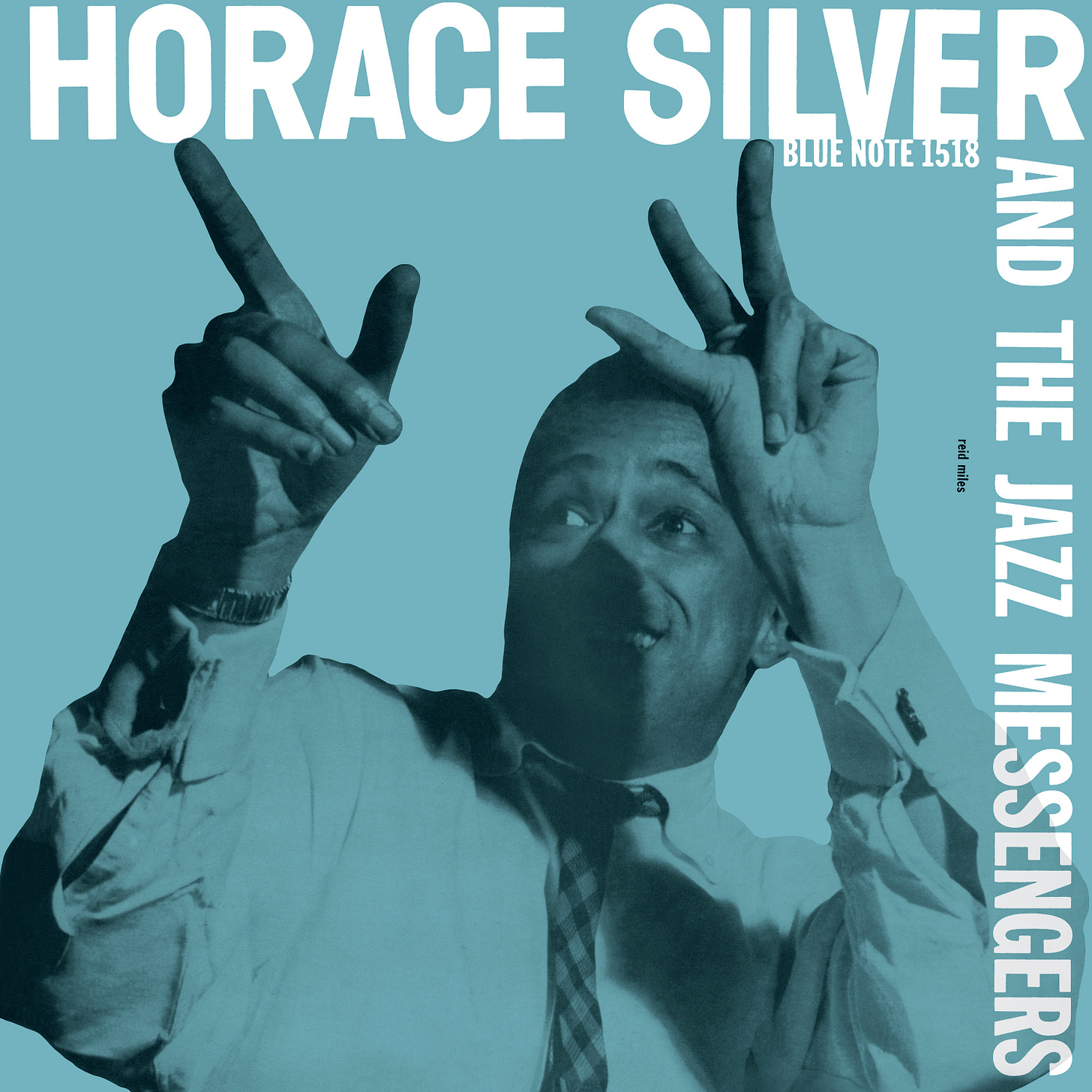

Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers, Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers

This album established the rigid bop template through Silver’s blues-based compositions and Kenny Dorham’s melodic trumpet lines. The quintet’s rhythmic drive stems from Silver’s percussive piano style and Art Blakey’s dynamic drumming. “The Preacher” merges church music influences with sophisticated jazz harmony.

Grant Green, I Want to Hold Your Hand

Green adapts Beatles melodies to jazz guitar vocabulary. His single-note lines extract harmonic possibilities from simple pop structures. Larry Young’s organ adds modal harmonies beneath the familiar themes. Elvin Jones transforms straight rock rhythms into polyrhythmic statements.

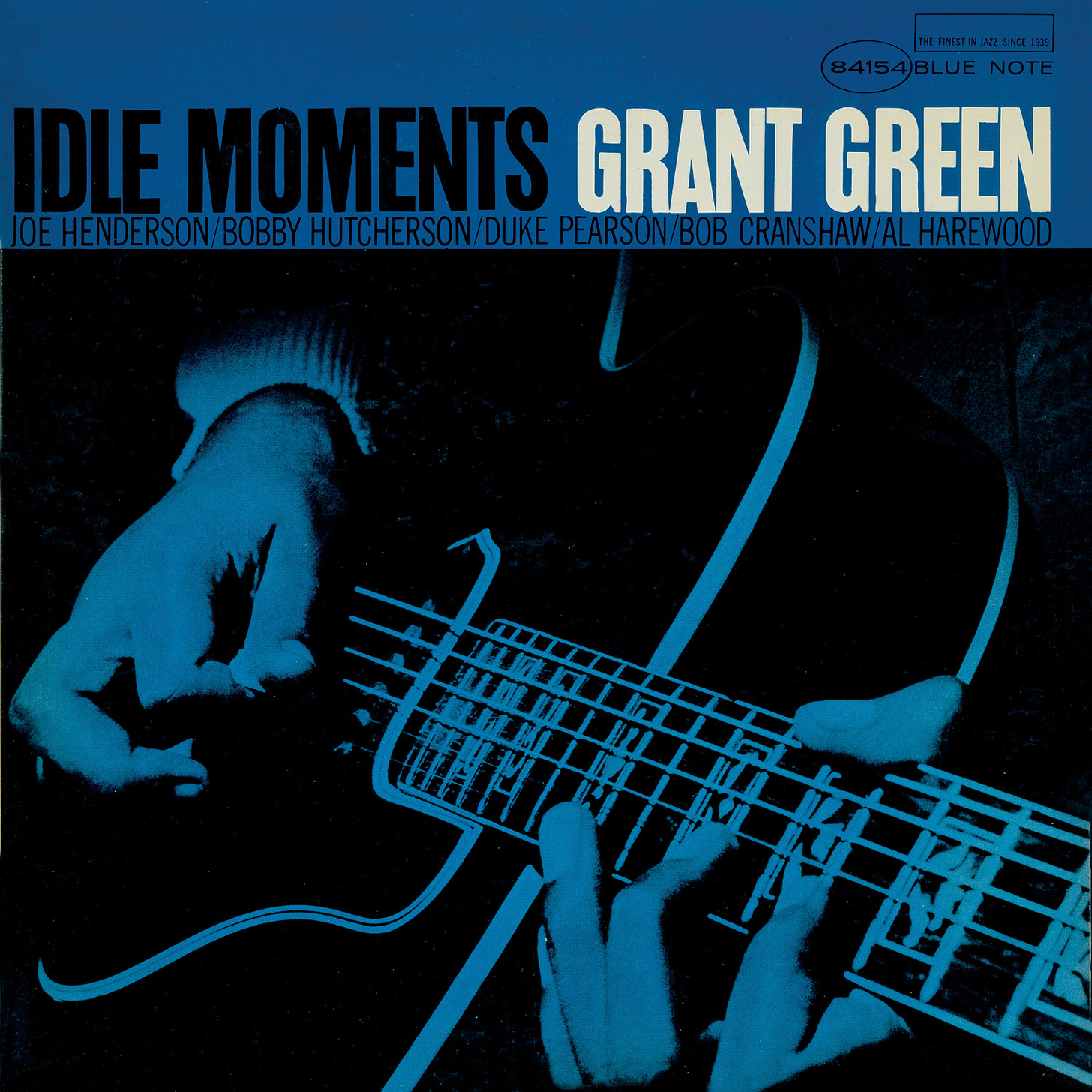

Grant Green, Idle Moments

Green’s guitar work highlights melodic clarity over technical display. The title track’s 16-bar phrases allow each soloist to develop ideas fully, with Joe Henderson’s tenor saxophone providing contrasting textures. Bobby Hutcherson’s vibraphone adds harmonic sophistication while maintaining the album’s meditative quality.

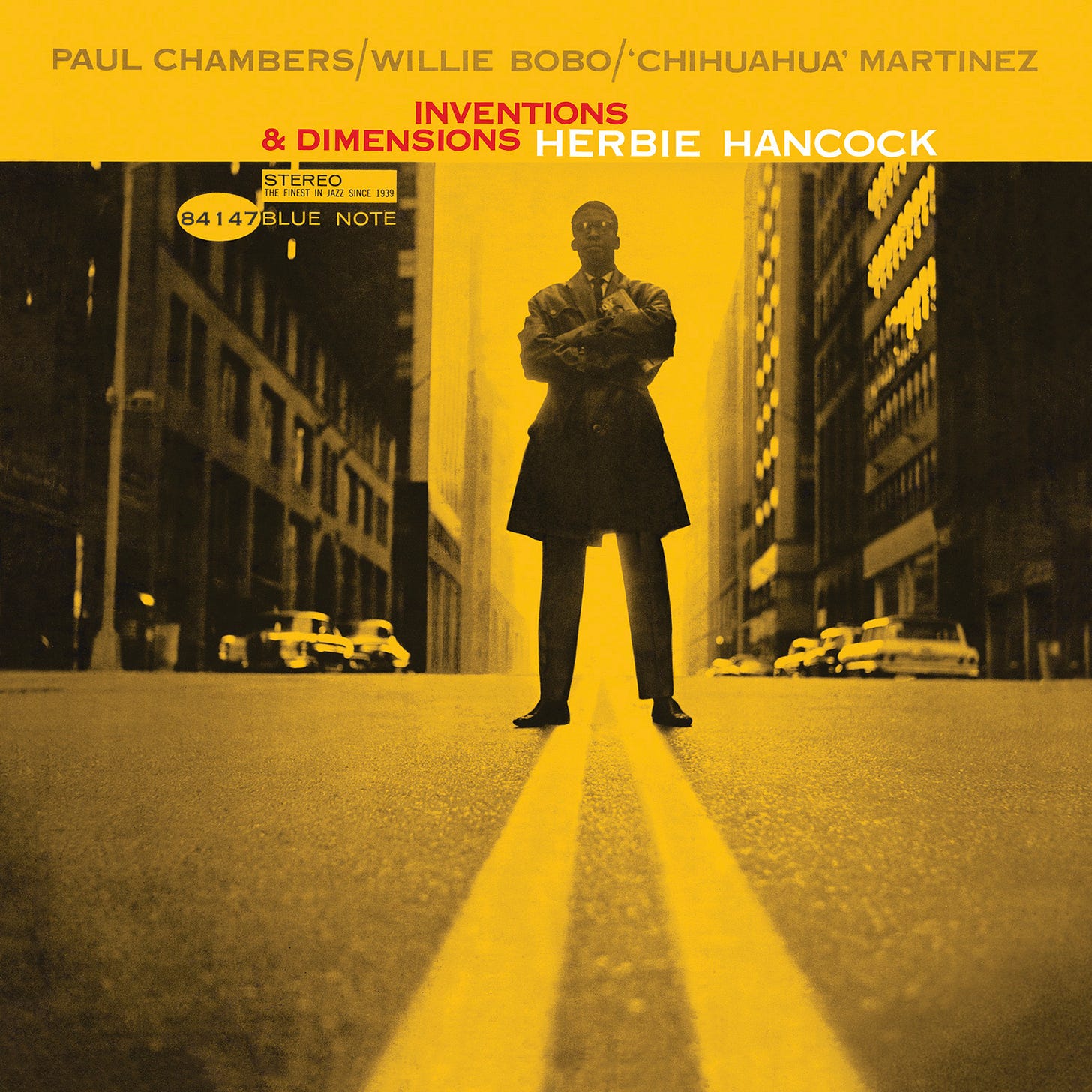

Herbie Hancock, Inventions & Dimensions

This Latin-influenced session strips away horns to highlight Hancock’s pianistic innovations. Paul Chambers’ bass and Willie Bobo’s percussion create rhythmic matrices for Hancock’s extended improvisations. “Triangle” demonstrates Hancock’s left-hand independence through counter-rhythms against Osvaldo Martinez’s conga patterns. The album’s unusual instrumentation allows full appreciation of Hancock’s harmonic concepts.

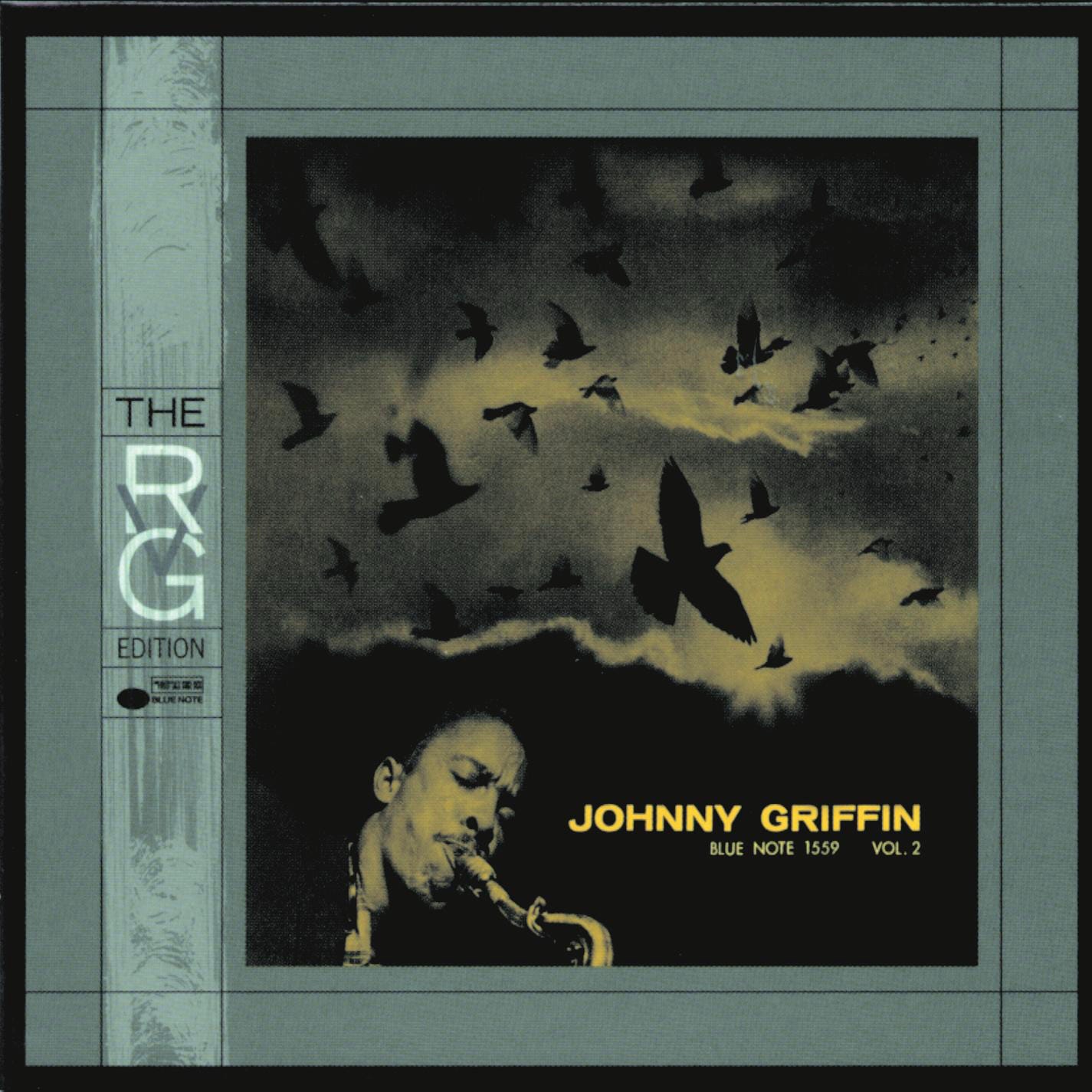

Johnny Griffin, Johnny Griffin, Vol. 2 (A Blowing Session)

Griffin’s alto saxophone technique bridges swing and bebop approaches. His quartet arrangements point out melodic development over technical display. Junior Mance’s piano adds blues authenticity to the harmonic structure. Paul Chambers’ bass solos match Griffin’s linear clarity.

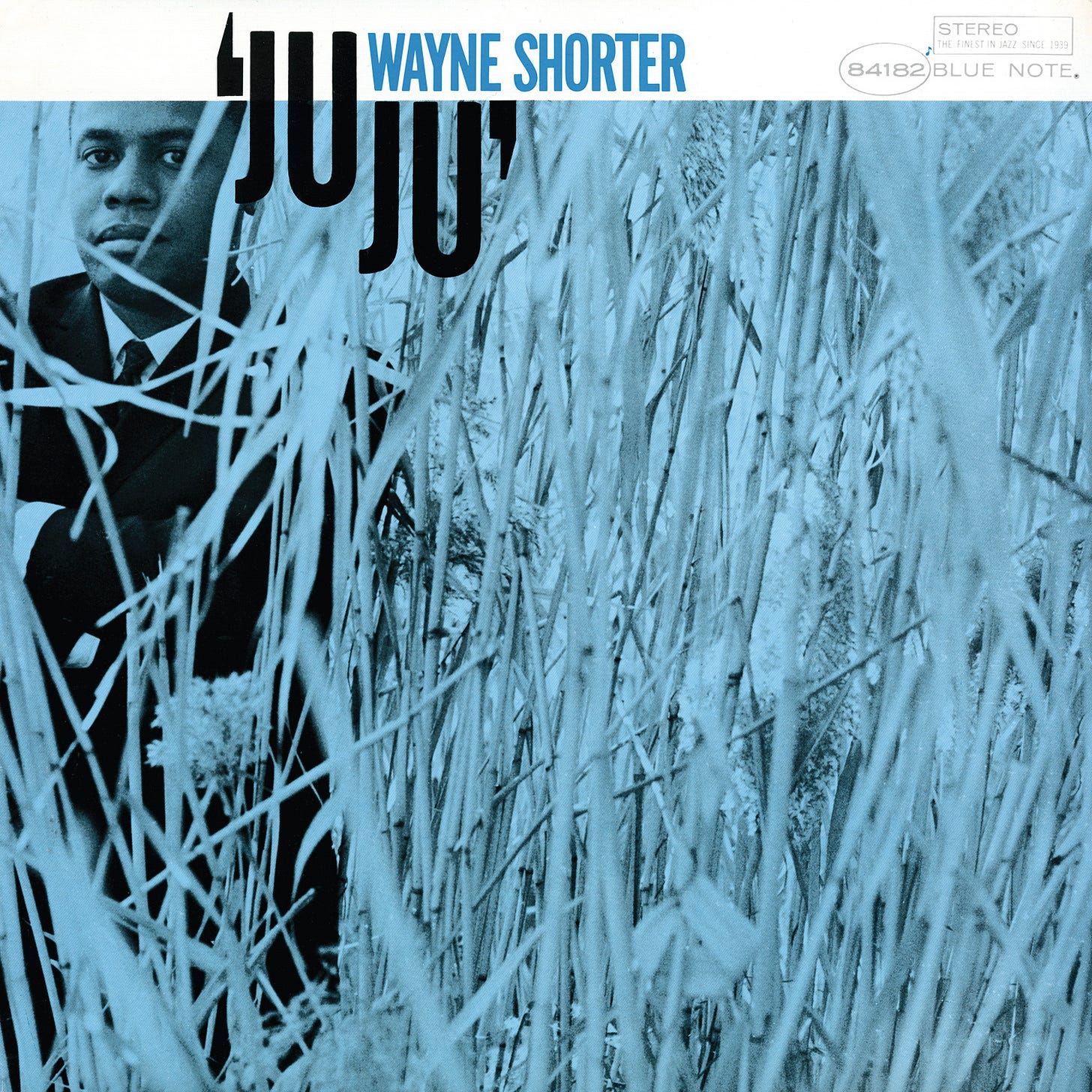

Wayne Shorter, JuJu

Recorded with John Coltrane’s rhythm section, this album merges modal frameworks with African-influenced rhythms. McCoy Tyner’s quartal harmony supports Shorter’s angular melodies, while Elvin Jones creates shifting metric patterns. “Deluge” showcases Shorter’s mathematical approach to composition, with precise motivic development throughout the solos.

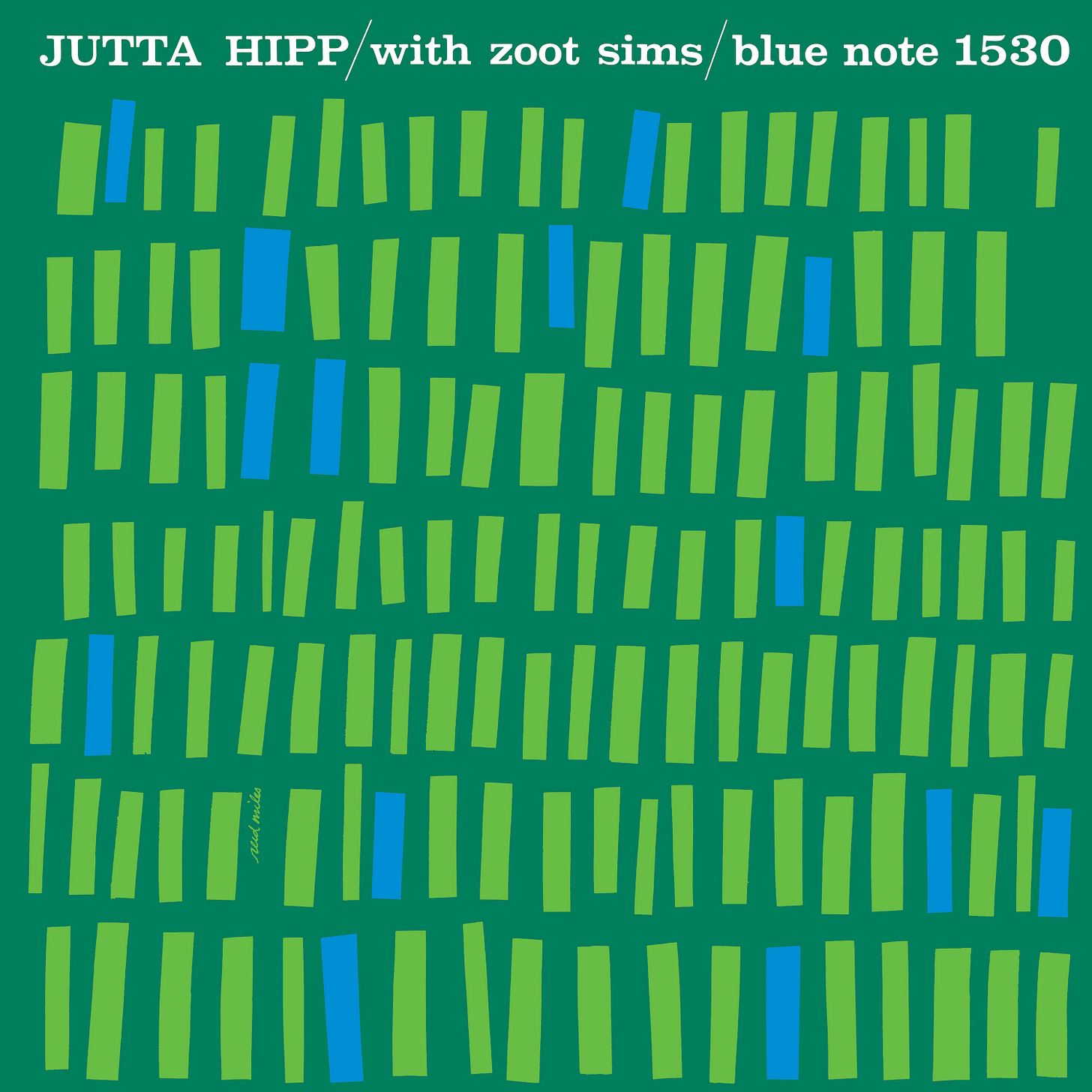

Jutta Hipp & Zoot Sims, Jutta Hipp with Zoot Sims

Hipp’s piano style combines European classical training with American jazz feeling. Sims’ tenor saxophone provides melodic authority through swing-based phrasing. The rhythm section balances German and American jazz approaches. Their collaboration documents the trans-Atlantic jazz exchange.

Big John Patton, Let ‘Em Roll

Patton’s organ work epitomizes rhythmic displacement over technical display. Grant Green’s guitar adds linear clarity to the organ’s thick textures. Bobby Hutcherson’s vibraphone creates unusual timbral combinations with the Hammond B3. Ben Dixon’s drums maintain a steady groove while responding to ensemble density changes.

Jackie McLean, Let Freedom Ring

McLean’s alto saxophone adapts bebop language to modern harmonic concepts. His slightly sharp intonation creates expressive tension throughout the album. Walter Davis’ piano voicings support McLean’s angular phrases while maintaining harmonic clarity. Billy Higgins’ drumming responds to the music’s emotional intensity through dynamic contrast.

Herbie Hancock, Maiden Voyage

Five original compositions chart new waters in modal jazz. The title track pairs Ron Carter’s bass ostinato with Tony Williams’ cymbal work, creating maritime suggestions without resorting to apparent effects. “The Eye of the Hurricane” demonstrates Freddie Hubbard’s precise articulation in high-speed passages, while George Coleman’s tenor saxophone adds warmth to the harmonic structures.

Geri Allen, Maroons

Allen’s compositions integrate African rhythmic concepts with contemporary harmony. Her piano technique incorporates angular phrases and unexpected accents, particularly evident in “Feed the Fire.” Marcus Belgrave’s trumpet adds historical continuity, while Tani Tabbal’s drums reference multiple cultural traditions. The trio format highlights Allen’s ability to suggest full ensemble textures through sophisticated voicing.

Grant Green, Matador

Green adapts his single-note style to modal jazz contexts with McCoy Tyner’s quartal piano harmonies. The title track demonstrates Green’s ability to build tension through repetitive phrases that gradually increase in complexity. Bob Cranshaw’s electric bass adds contemporary tonal colors, and Elvin Jones provides polyrhythmic support, characteristic of Coltrane’s quartet.

Kenny Burrell, Midnight Blue

Burrell’s guitar work spotlights tonal subtleties and blues inflections. Ray Barretto’s conga adds Latin elements to Stanley Turrentine’s blues-drenched tenor saxophone lines. “Chitlins Con Carne” demonstrates Burrell’s ability to construct solos that balance sophisticated jazz harmony with raw emotional appeal. The rhythm section maintains a consistent groove while allowing space for detailed guitar articulation.

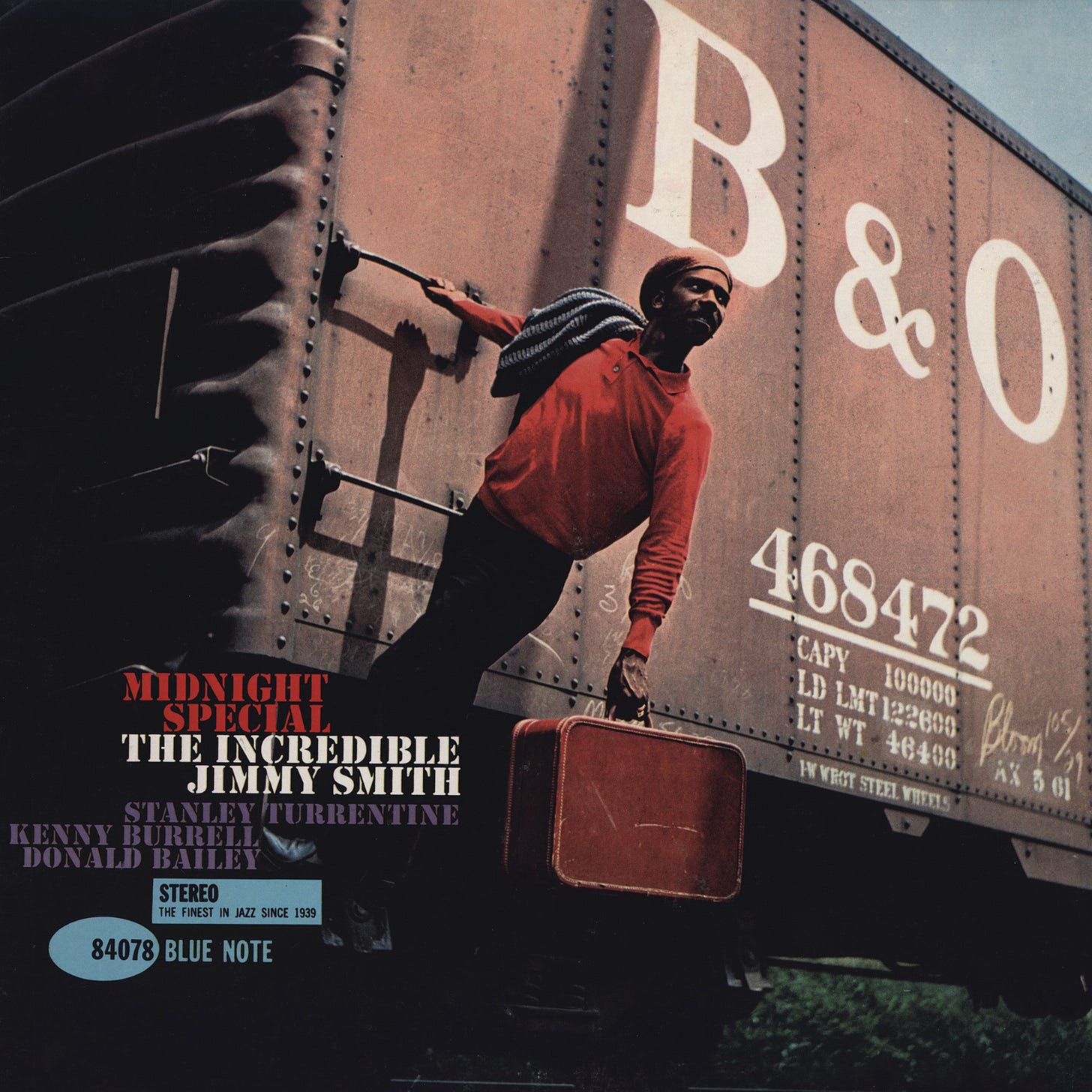

Jimmy Smith, Midnight Special

Smith revolutionized the Hammond B3 organ’s role in jazz. His bass pedal technique allows him to function as both bassist and soloist, demonstrated clearly on “One O’Clock Jump.” Stanley Turrentine’s tenor saxophone adds blues inflections, while Kenny Burrell’s guitar provides rhythmic counterpoint. The trio format creates maximum space for Smith’s innovative organ vocabulary.

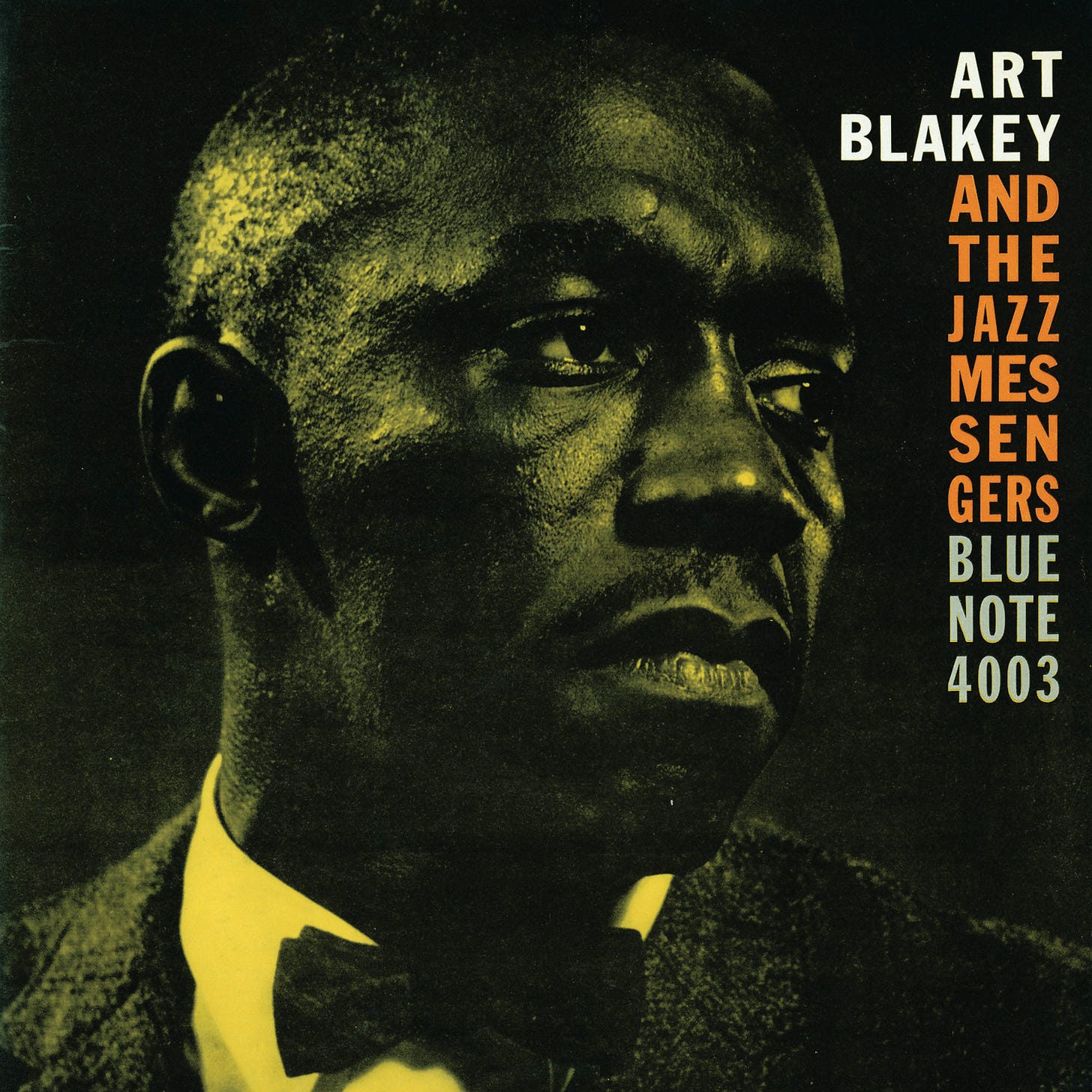

Art Blakey & the Jazz Messengers, Moanin’

The definitive hard bop album pairs Blakey’s thunderous drums with Lee Morgan’s bright trumpet and Benny Golson’s arrangements. “Blues March” introduces military cadences to jazz rhythm, while Bobby Timmons’ gospel-influenced title track became a jazz standard. The sextet’s unified ensemble playing and fiery solos exemplify the Jazz Messengers’ workshop approach to developing young talent.

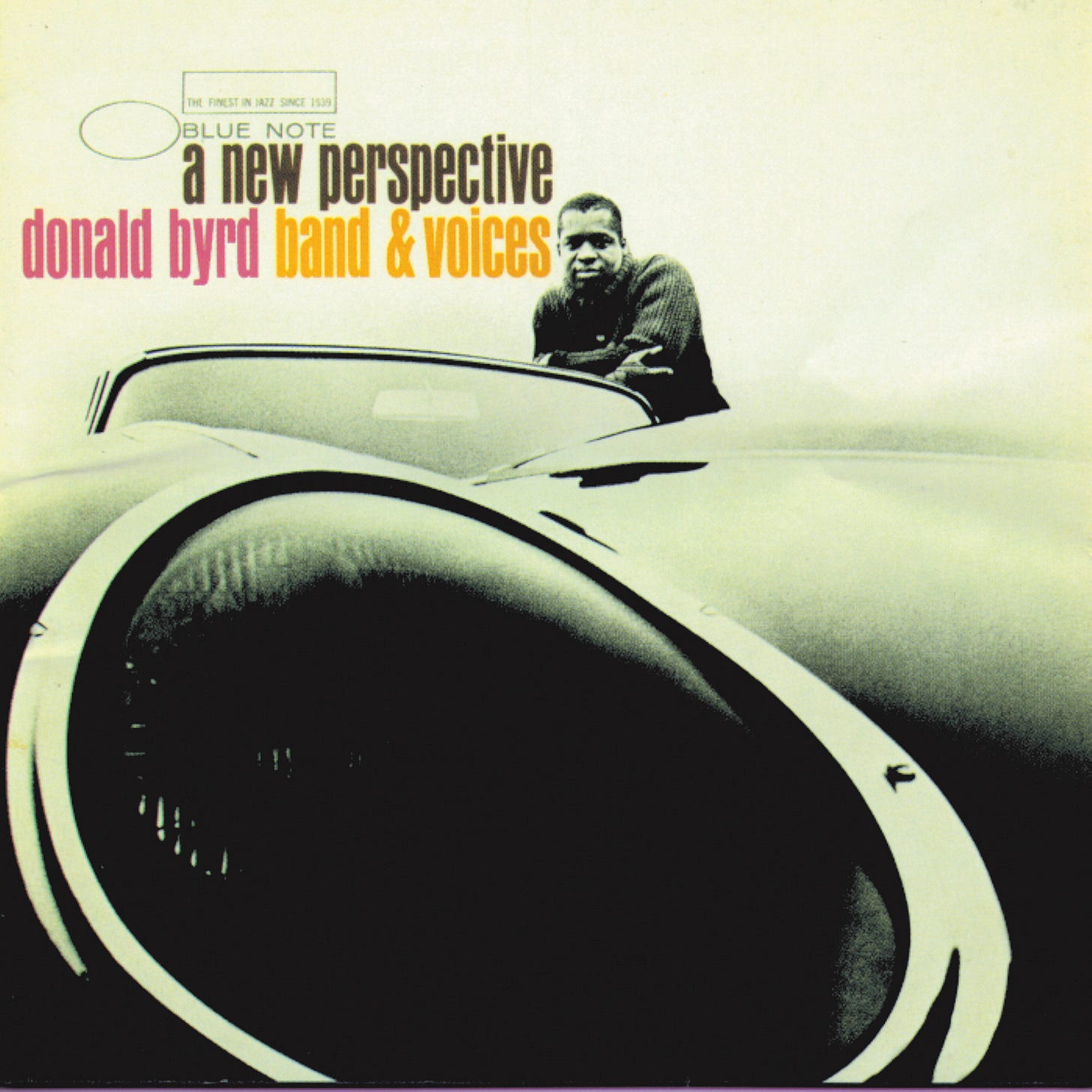

Donald Byrd, A New Perspective

Byrd integrates gospel choir with jazz quintet, expanding the music’s textural palette. Duke Pearson’s arrangements maintain clarity despite the enlarged ensemble. “Cristo Redentor” pairs Byrd’s muted trumpet with vocal harmonies in unprecedented ways. Herbie Hancock’s piano bridges sacred and secular musical approaches.

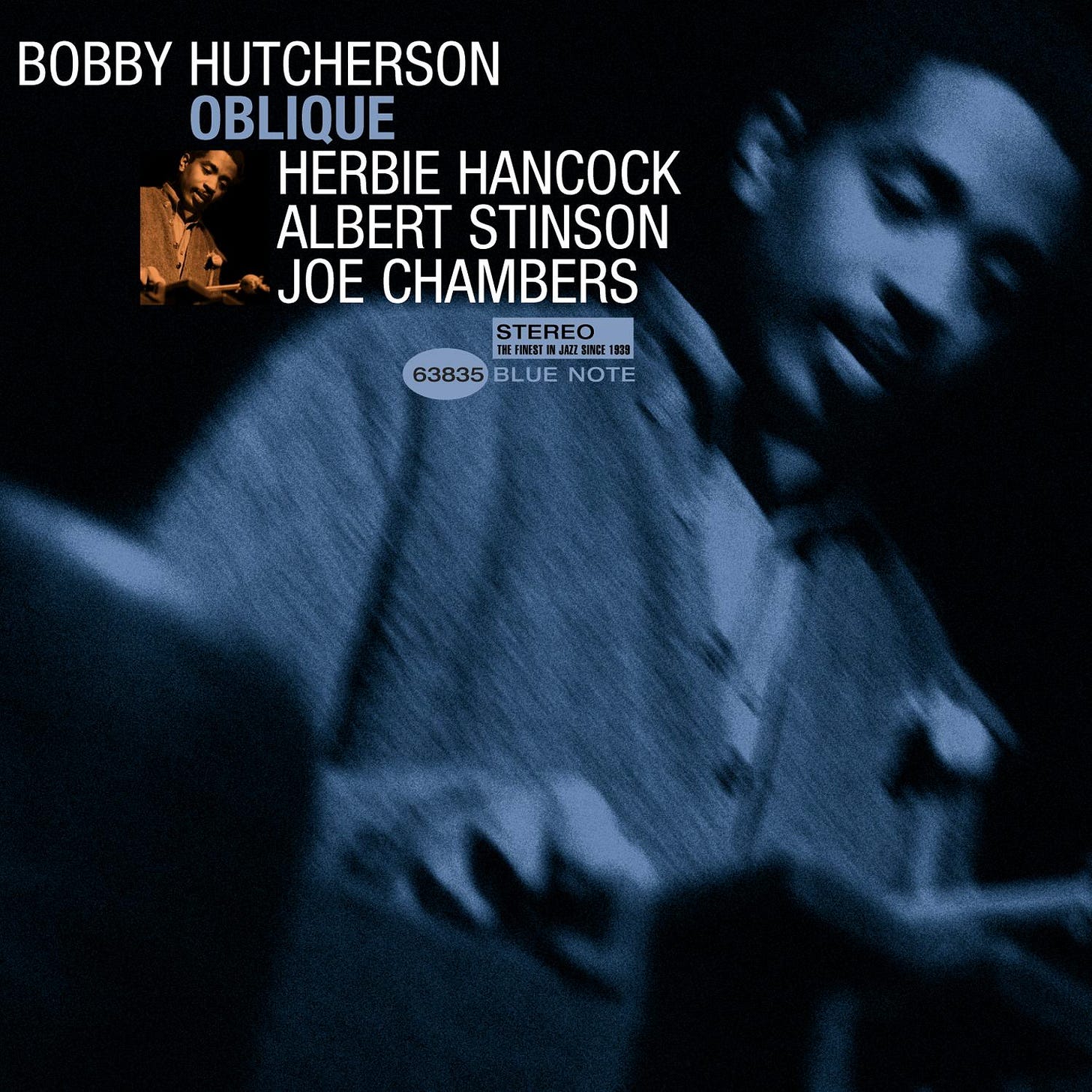

Bobby Hutcherson, Oblique

The album pairs Hutcherson’s vibraphone with Herbie Hancock’s piano in complex harmonic dialogue. Albert Stinson’s bass creates independent countermelodies, and Joe Chambers’ drums add textural variety through cymbal colors. The title composition demonstrates Hutcherson’s ability to write for unusual formal structures while maintaining musical coherence.

Jackie McLean, One Step Beyond

McLean adapts his alto saxophone approach to incorporate free jazz elements. Grachan Moncur III’s trombone adds compositional depth through unusual intervallic relationships. Bobby Hutcherson’s vibraphone replaces the piano, creating more open harmonic spaces. Tony Williams’ drums anticipate the metric flexibility he later brought to Miles Davis’s quintet.

Dexter Gordon, Our Man In Paris

Gordon’s tenor saxophone articulation adapts bebop language for modern contexts. His behind-the-beat phrasing creates tension against Bud Powell’s precise piano time. Kenny Clarke’s drumming adds Parisian jazz sophistication to American bebop roots. “Scrapple from the Apple” highlights Gordon’s ability to quote musical references and maintain improvisational flow.

Eric Dolphy, Out to Lunch!

Dolphy’s final Blue Note recording breaks conventional jazz structures while maintaining musical coherence. His bass clarinet on “Something Sweet, Something Tender” exhibits microtonality and extended techniques unprecedented in jazz. Bobby Hutcherson’s vibraphone creates abstract harmonies, while Tony Williams’ drumming fragments time without losing the pulse. Freddie Hubbard adapts his trumpet technique to match Dolphy’s adventurous phrases.

Joe Henderson, Page One

Henderson’s tenor saxophone compositions intensify structural innovation. Kenny Dorham’s trumpet adds melodic precision to the ensemble blend. McCoy Tyner’s piano creates harmonic foundations for modal exploration. Butch Warren’s bass maintains forward momentum through shifting meters.

Andrew Hill, Point of Departure

Hill’s piano compositions challenge standard jazz forms through asymmetrical phrases and shifting meters. Eric Dolphy’s alto saxophone and Kenny Dorham’s trumpet navigate the complex structures with remarkable precision. Joe Henderson provides a tenor saxophone counterpoint that bridges traditional and progressive approaches. Tony Williams’ drumming anticipates metric modulations before they occur.

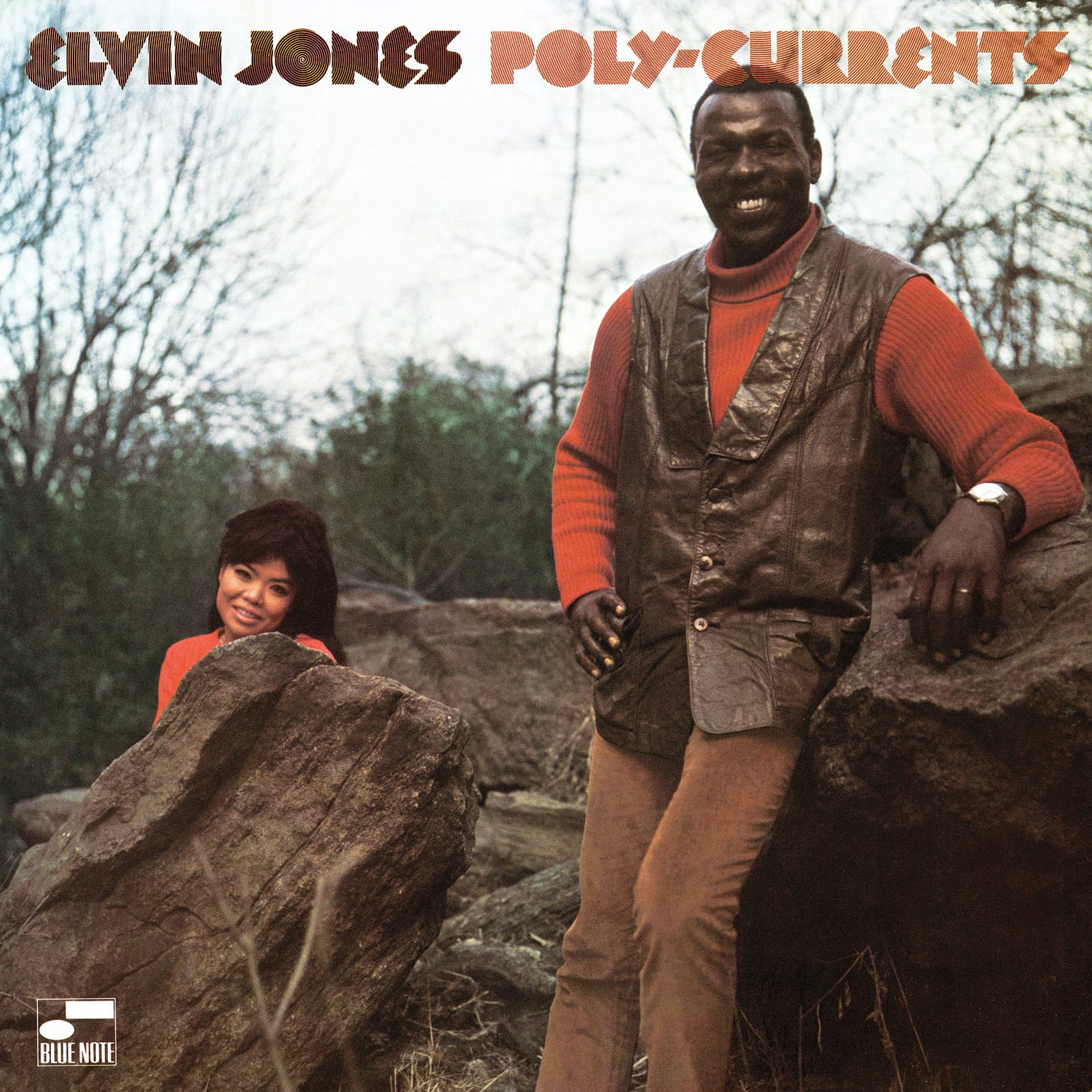

Elvin Jones, Poly-Currents

Jones’ drumming leads the ensemble through complex metric structures. Joe Farrell’s soprano saxophone navigates shifting rhythmic patterns. George Coleman’s tenor adds harmonic weight to the front line. Wilbur Little’s bass anchors the polyrhythmic jaunts.

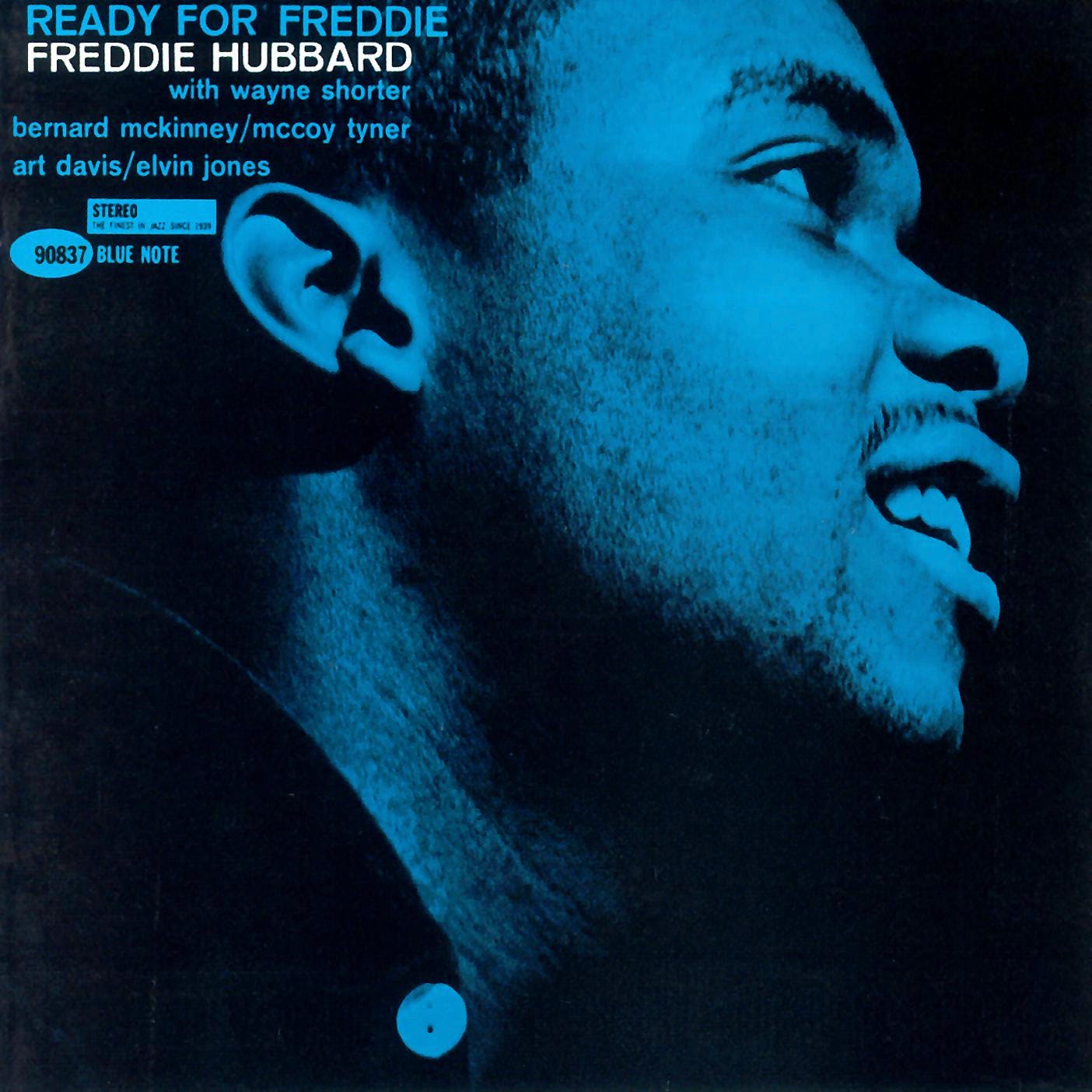

Freddie Hubbard, Ready for Freddie

Hubbard’s trumpet technique combines blazing speed with harmonic sophistication. Bernard McKinney’s euphonium adds unusual timbral combinations to the front line. “Birdlike” demonstrates Hubbard’s absorption of bebop vocabulary into modern contexts. Wayne Shorter’s tenor saxophone provides complementary linear approaches, whereas McCoy Tyner’s piano creates modal harmonic foundations.

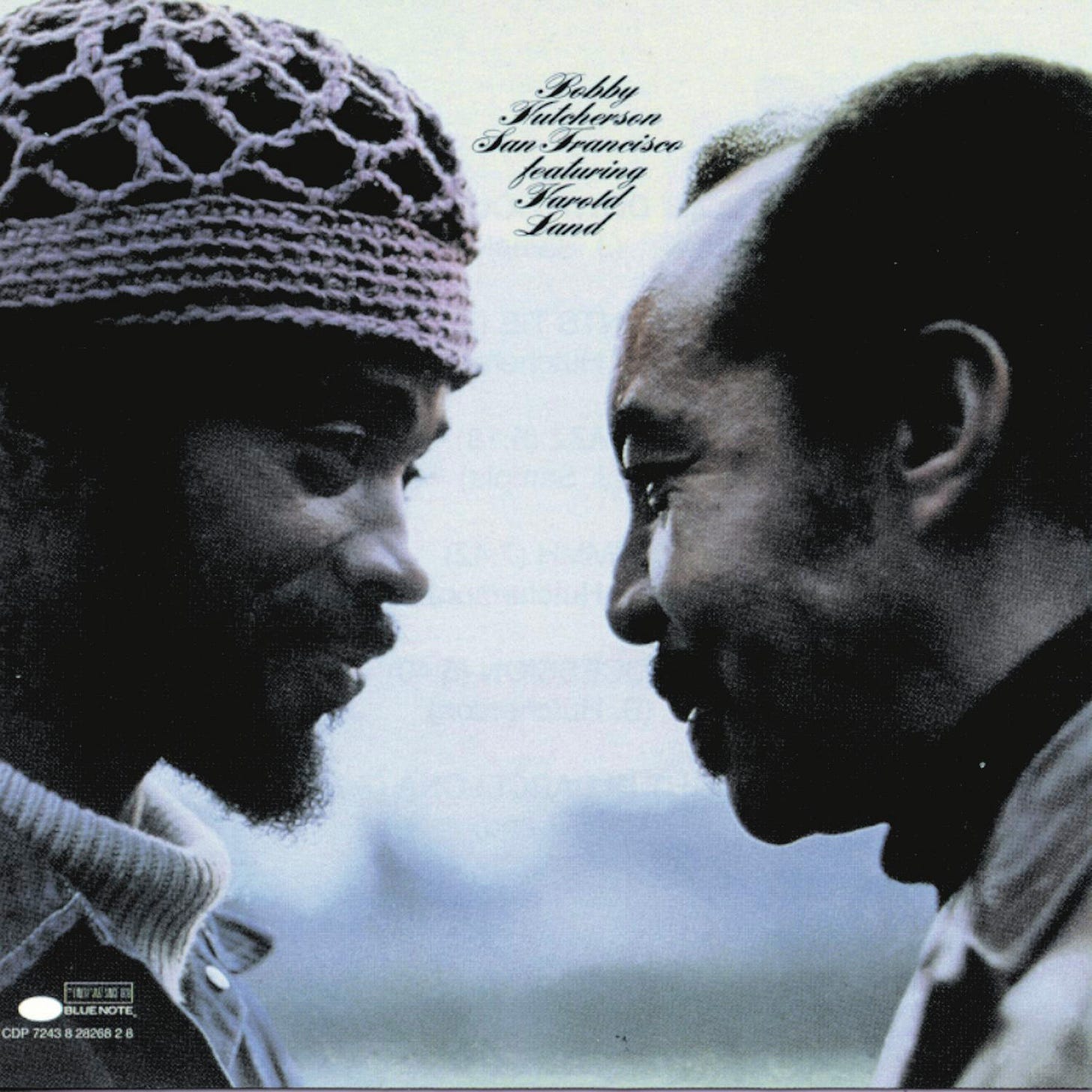

Bobby Hutcherson, San Francisco

Hutcherson’s vibraphone adapts to freer musical contexts. Harold Land’s tenor saxophone provides melodic continuity through abstract passages. Joe Chambers’ drums respond to textural density changes. The album documents Bay Area jazz developments.

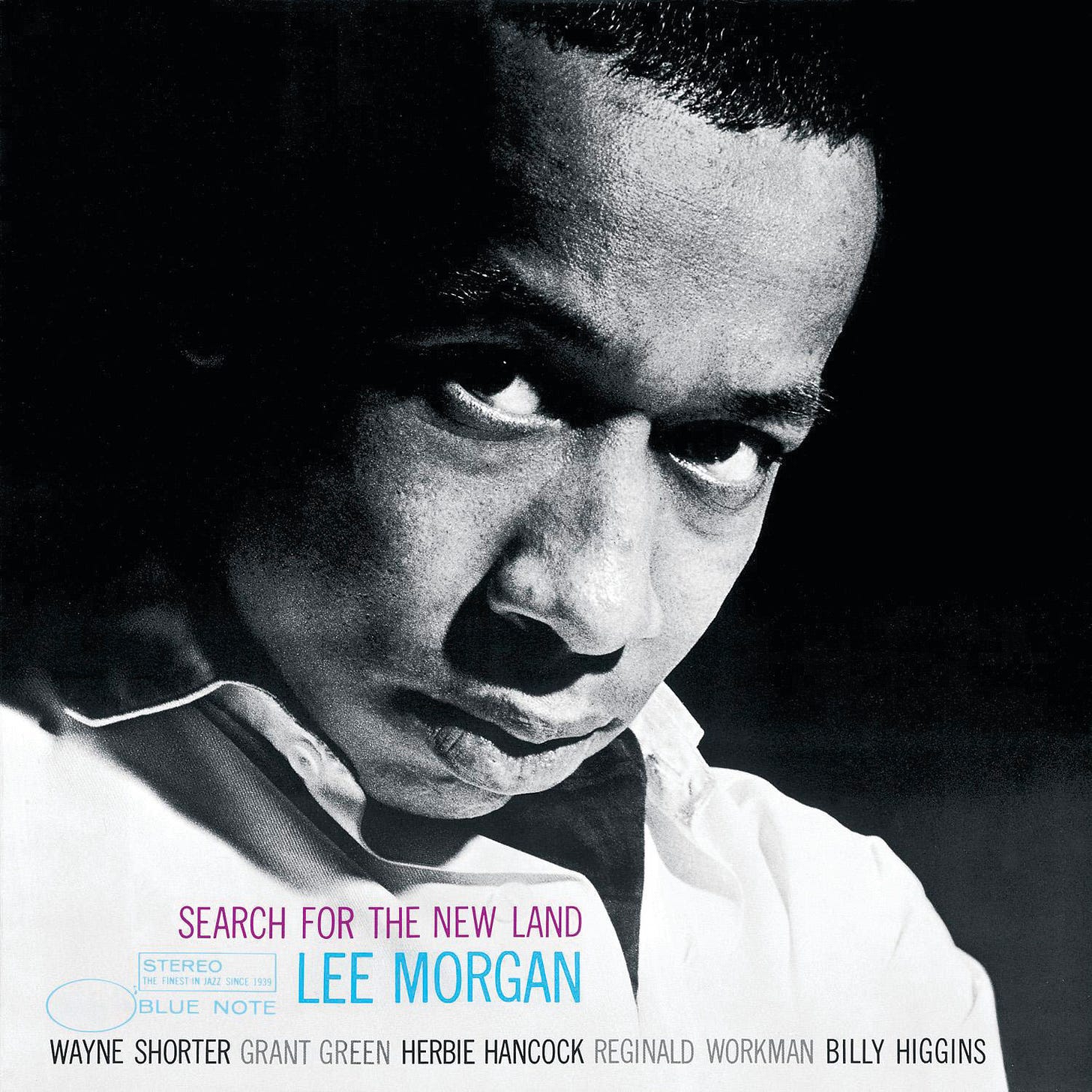

Lee Morgan, Search for a New Land

Morgan’s compositions balance structural complexity with blues authenticity. Grant Green’s guitar adds textural variety to the horn arrangements. “Mr. Kenyatta” showcases Morgan’s ability to construct extended solos with clear narrative development. Wayne Shorter’s tenor work provides an architectural counterpoint to Morgan’s trumpet statements.

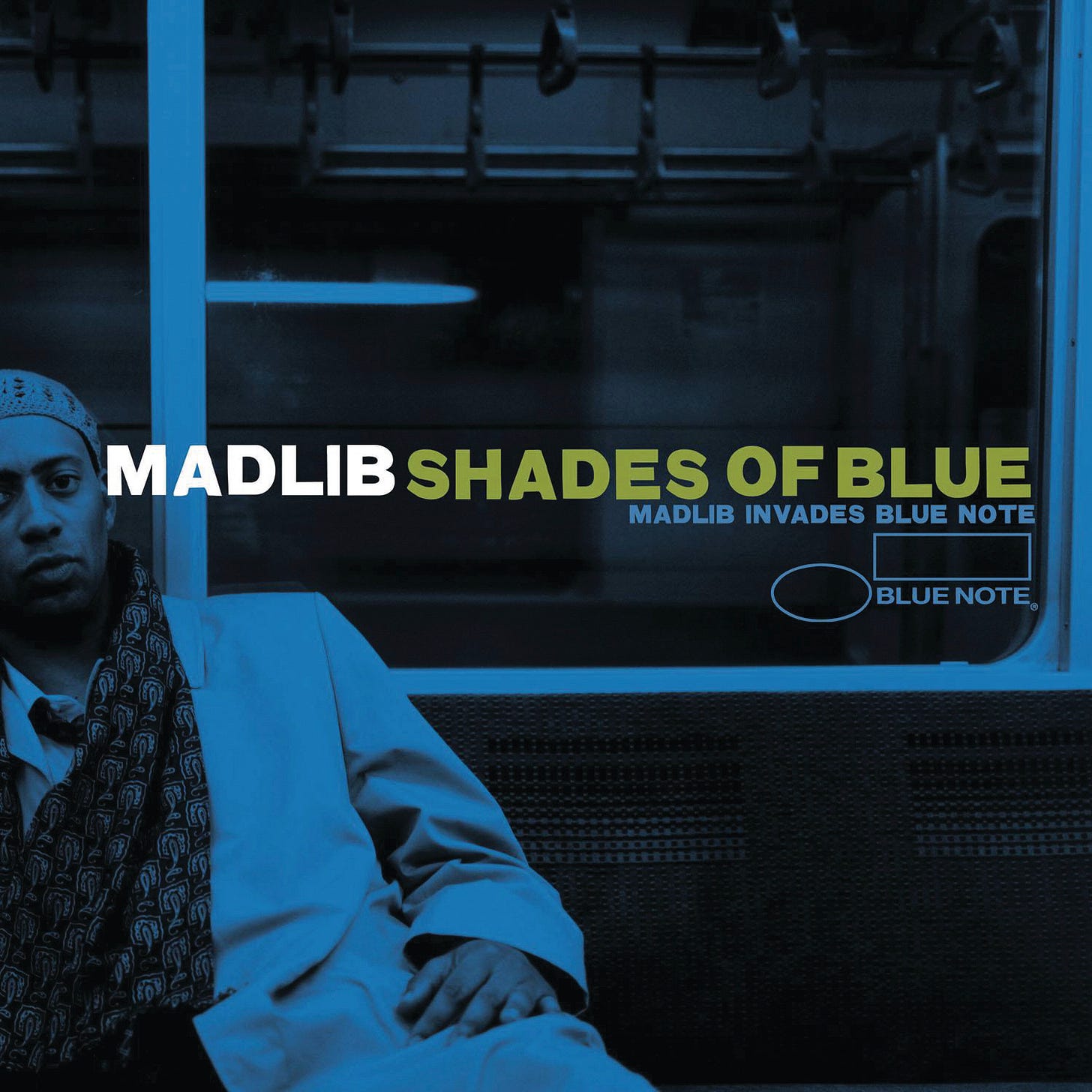

Madlib, Shades of Blue: Madlib Invades Blue Note

This reconstruction project samples Blue Note classics through hip-hop production techniques. “Slim’s Return” reframes Donald Byrd’s trumpet phrases in new rhythmic contexts. The album maintains Blue Note’s dedication to groove while adding contemporary production values. Original compositions interact with samples to create musical dialogue across decades.

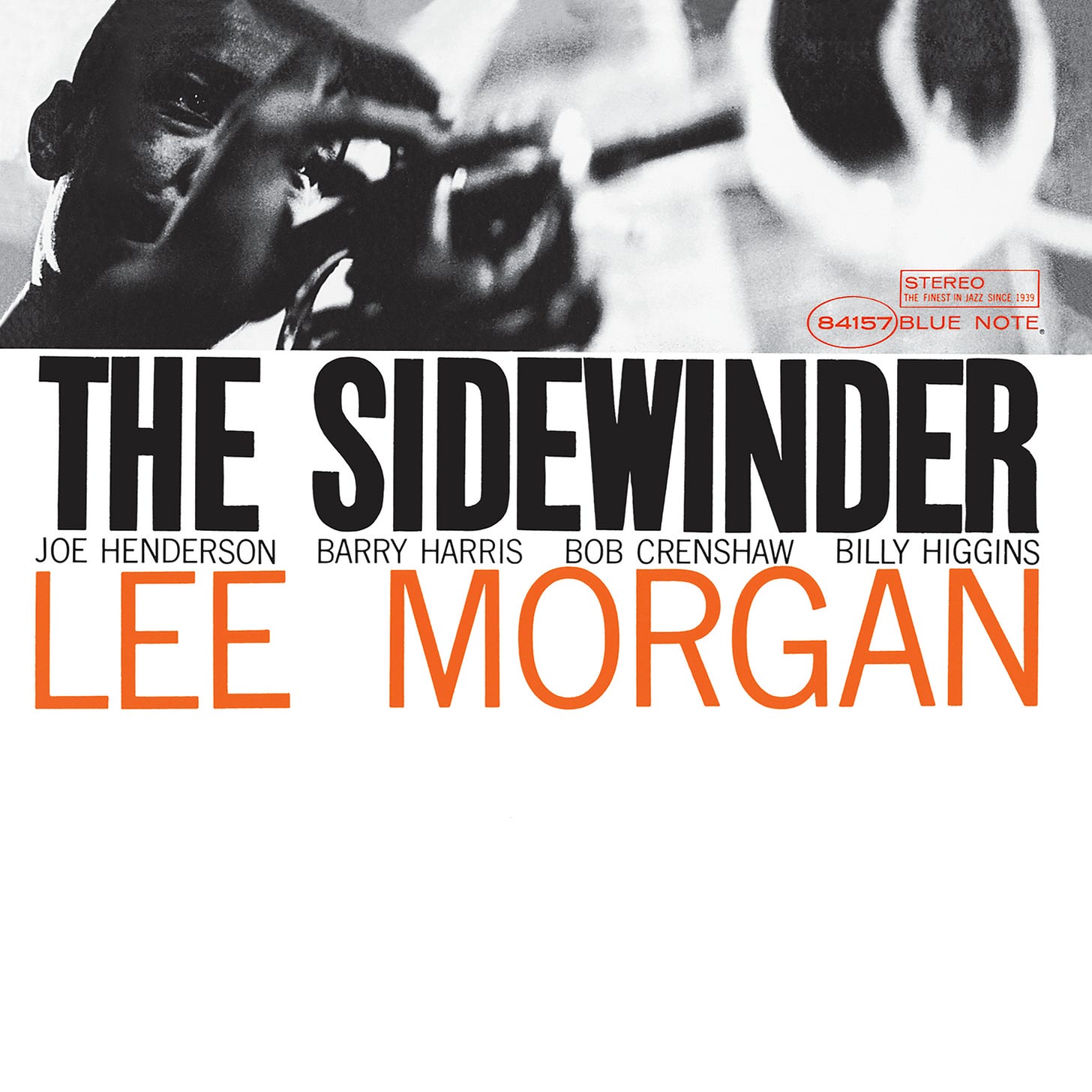

Lee Morgan, The Sidewinder

Morgan’s trumpet leads a quintet through five original compositions highlighting his melodic gifts. The title track’s boogaloo rhythm influenced numerous subsequent Blue Note recordings. Joe Henderson’s tenor saxophone provides a thoughtful counterpoint to Morgan’s declarative style. Barry Harris’ piano solos build through logical harmonic progression while maintaining rhythmic drive.

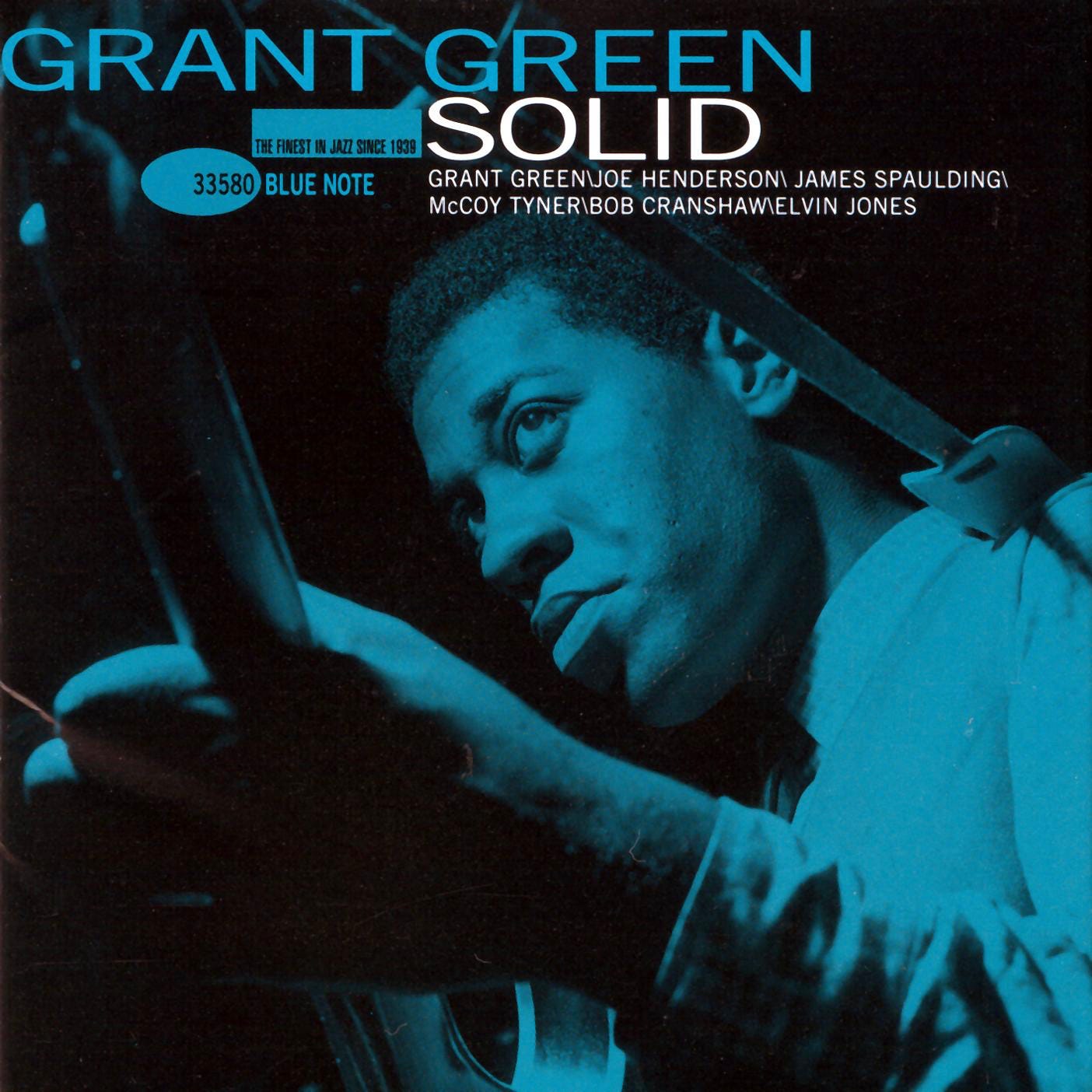

Grant Green, Solid

Green’s interpretive skills shine through standards and originals. James Spaulding’s alto flute adds timbral variety to the ensemble sound. Bob Cranshaw’s electric bass forecasts future jazz-funk developments. Al Harewood’s drums maintain subtle rhythmic commentary throughout.

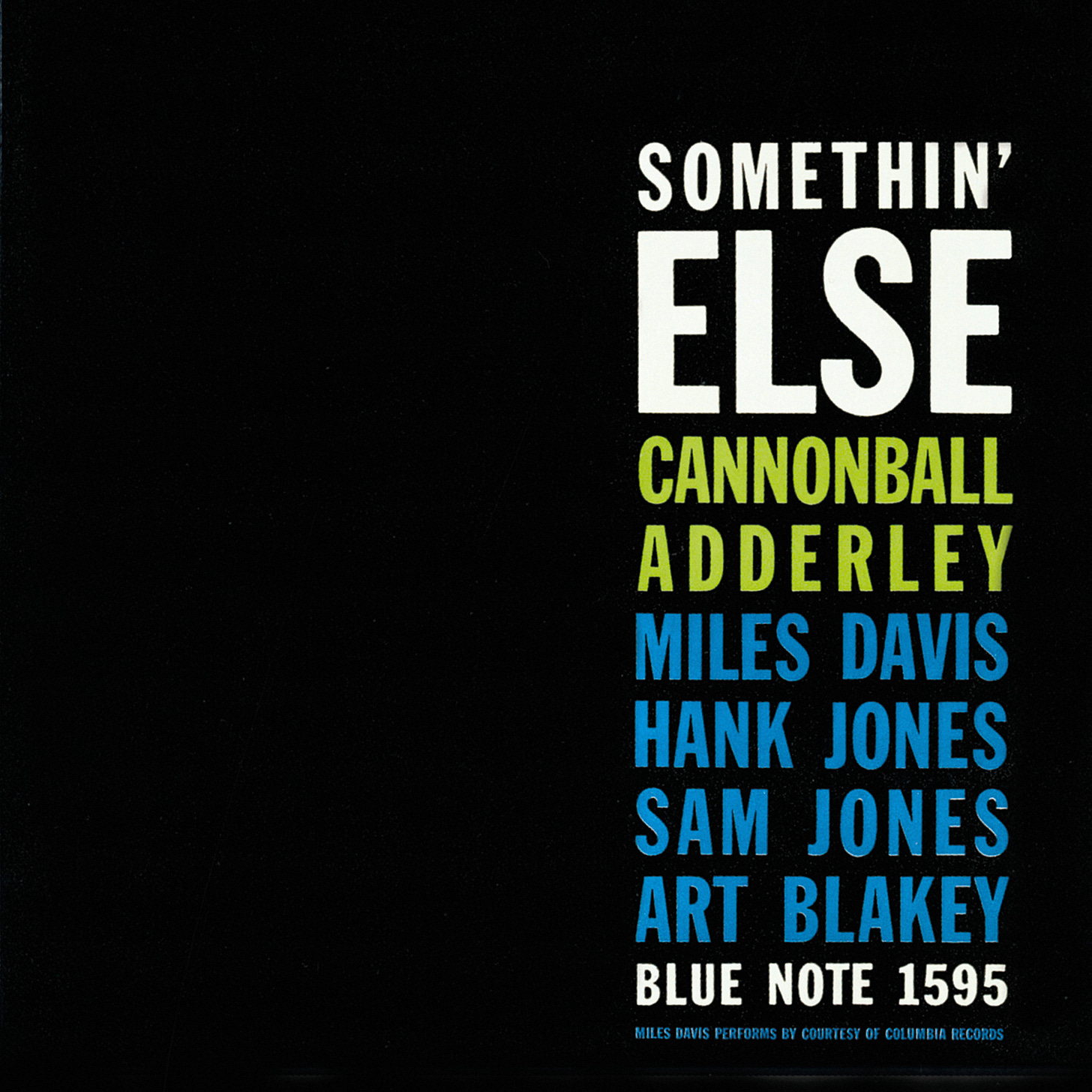

Cannonball Adderley, Somethin’ Else

Adderley interlocks alto saxophone lines with Miles Davis’ trumpet in brilliant collective dialogue. Art Blakey propels the ensemble with characteristic fire while Sam Jones establishes the rhythmic core. Hank Jones paints sophisticated harmonic backdrops. This rare Davis sideman appearance captures unrepeatable musical chemistry.

The Horace Silver Quintet, Song for My Father

Silver’s compositions mingle Cape Verdean cadences with hard bop language. Joe Henderson’s tenor saxophone adds architectural strength to Silver’s piano figures. Carmell Jones’ trumpet brings linear clarity to ensemble passages. Roger Humphries’ drums adapt Latin patterns to jazz contexts.

Sonny Clark Trio, Sonny Clark Trio (1957)

Clark’s piano technique balances bebop complexity with blues feeling. His left-hand stride patterns support right-hand melodic inventions. Paul Chambers’ bass solos match Clark’s melodic sophistication. Philly Joe Jones’ drums add rhythmic commentary while maintaining the swing foundation.

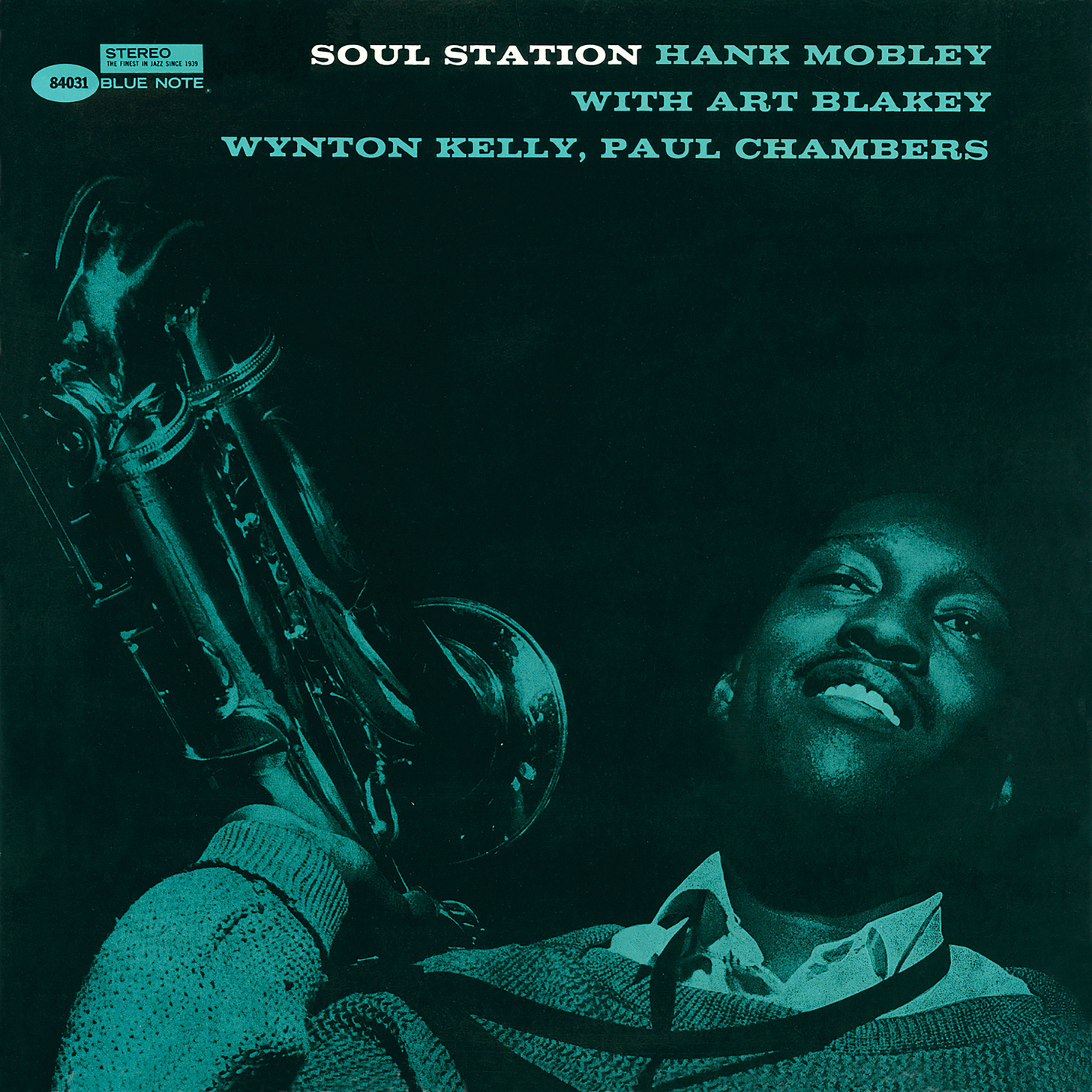

Hank Mobley, Soul Station

Mobley’s tenor saxophone exhibits his distinctive middle-register authority throughout four originals and two standards. Art Blakey’s drums and Paul Chambers’ bass create a swinging foundation that allows Mobley to construct logical solo narratives. Wynton Kelly’s piano accompaniment demonstrates subtle rhythmic displacement while maintaining the blues feeling.

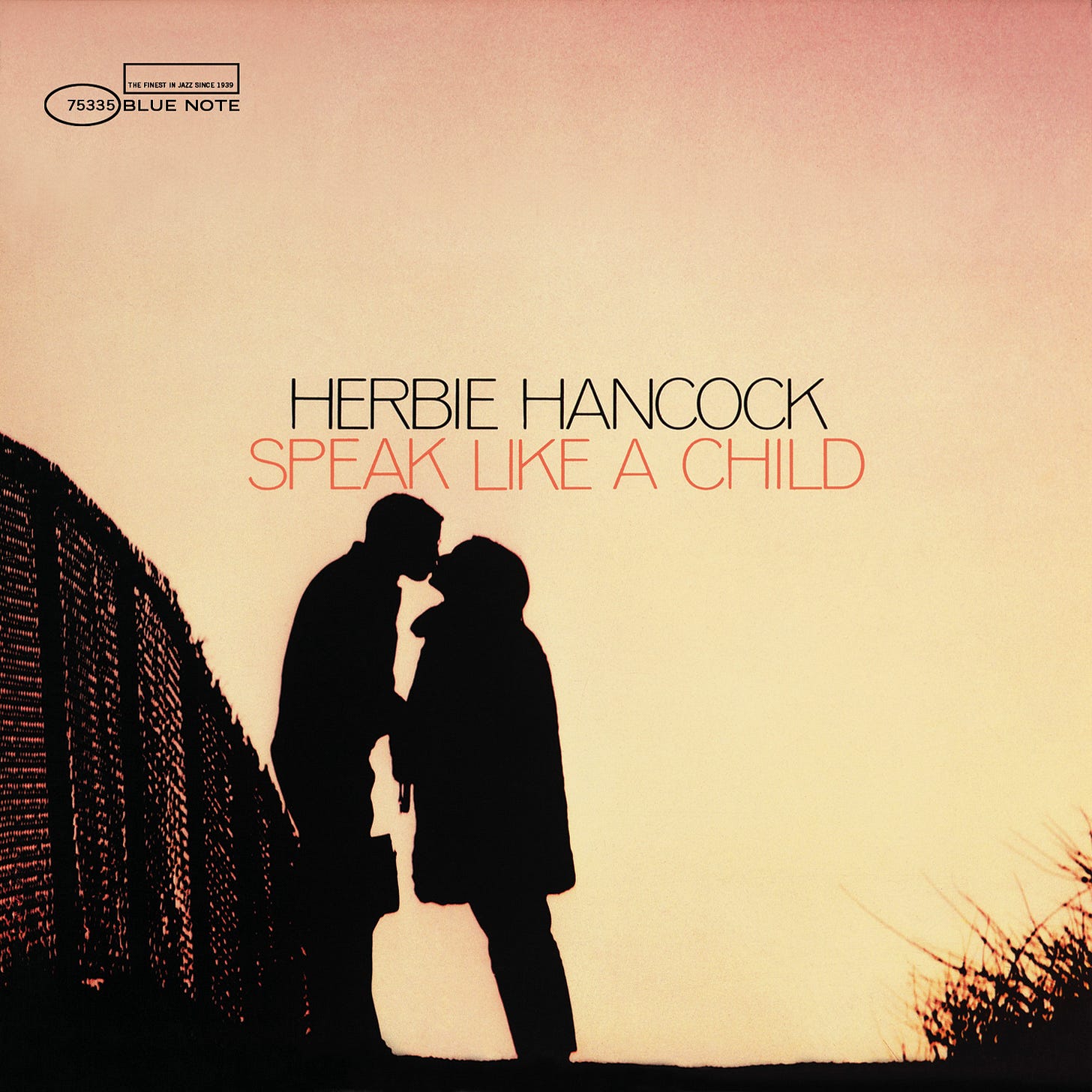

Herbie Hancock, Speak Like a Child

Hancock’s compositions underline orchestral colors through unusual horn voicings. Thad Jones’ flugelhorn adds warm timbres to ensemble passages. Peter Phillips’ bass trombone provides a harmonical foundation. Ron Carter’s bass maintains melodic independence throughout.

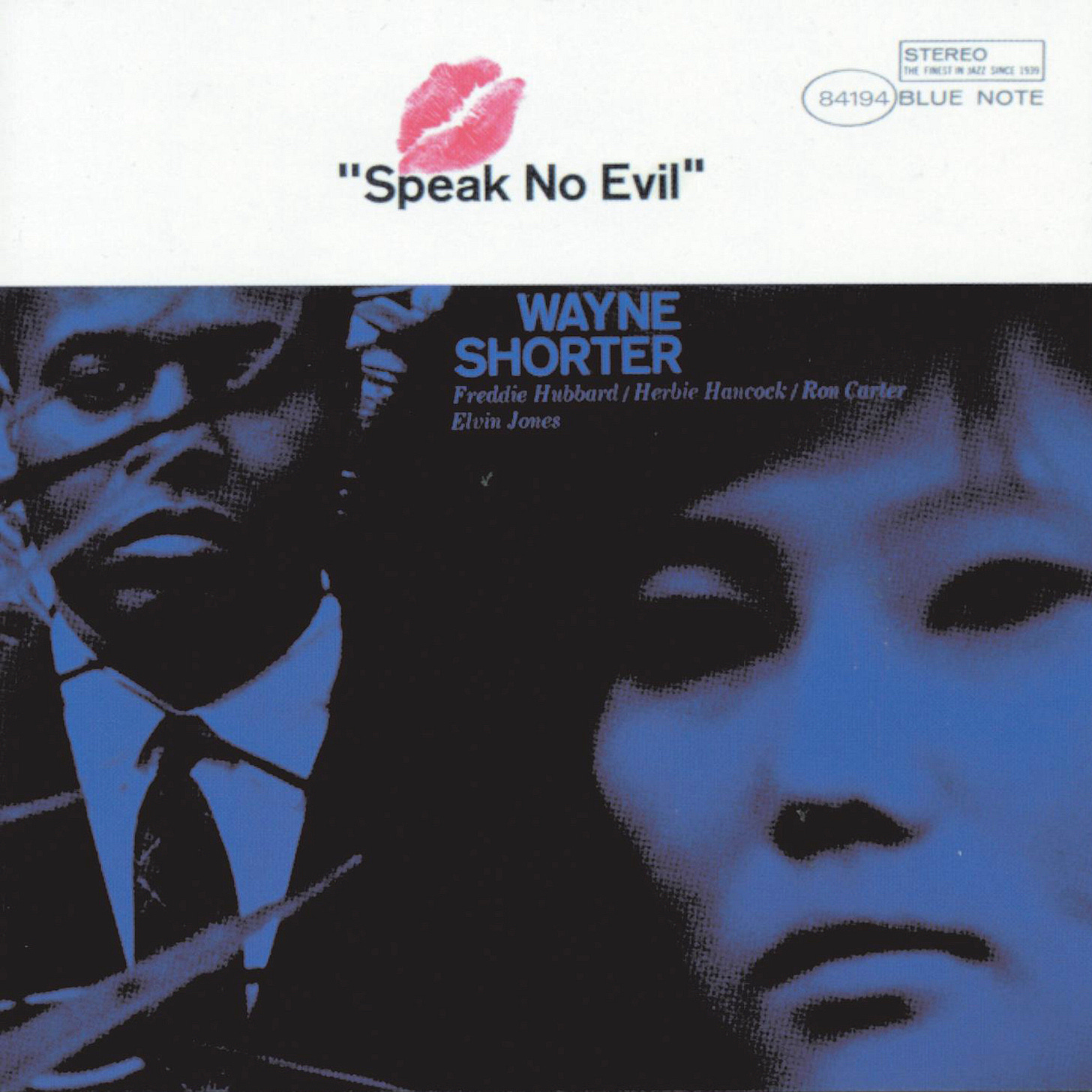

Wayne Shorter, Speak No Evil

Shorter’s compositions on this album redefined harmonic possibilities in small-group jazz. The interplay between his tenor saxophone and Freddie Hubbard’s trumpet creates architectural melodic lines, particularly in “Witch Hunt.” Herbie Hancock’s piano voicings and Elvin Jones’ polyrhythmic drumming add textural depth. Ron Carter’s bass lines anchor the free-flowing improvisations while maintaining forward momentum.

Bobby Hutcherson, Stick-Up!

Hutcherson’s vibraphone technique extends the instrument’s textural possibilities. Joe Henderson’s tenor saxophone provides a melodic foundation, while McCoy Tyner’s piano adds harmonic density. “Black Circle” shows Hutcherson’s four-mallet technique in compositional and improvisational contexts. Billy Higgins’ drums respond to the music’s shifting densities with appropriate dynamic control.

Hank Mobley, Straight No Filter

Mobley’s tenor saxophone exhibits mature stylistic development. Lee Morgan’s trumpet adds rhythmic precision to ensemble passages. Herbie Hancock’s piano creates modern harmonic contexts. The rhythm section balances tradition with innovation.

Herbie Hancock, Takin’ Off

Hancock’s leadership debut unveils his distinctive compositional voice. Freddie Hubbard ignites the ensemble with incisive trumpet lines. Dexter Gordon enriches the compositions with authoritative tenor statements.

Grant Green, Talkin’ About!

Green’s quartet setting highlights his blues-based improvisational approach. Sam Jones’ bass creates a melodic counterpoint to the guitar lines. Art Blakey’s drums add rhythmic intensity through strategic accents. The absence of a piano makes Green’s harmonic implications clear.

Stanley Turrentine, That’s Where It’s At

Turrentine fuses blues authenticity with sophisticated jazz harmony. Herbie Hancock’s piano voicings support the tenor saxophone’s emotional directness. Butch Warren’s bass maintains a rhythmic foundation, but on the other hand, Billy Higgins’ drums add dynamic subtlety. The title track exhibits Turrentine’s ability to build intensity through repeated phrases.

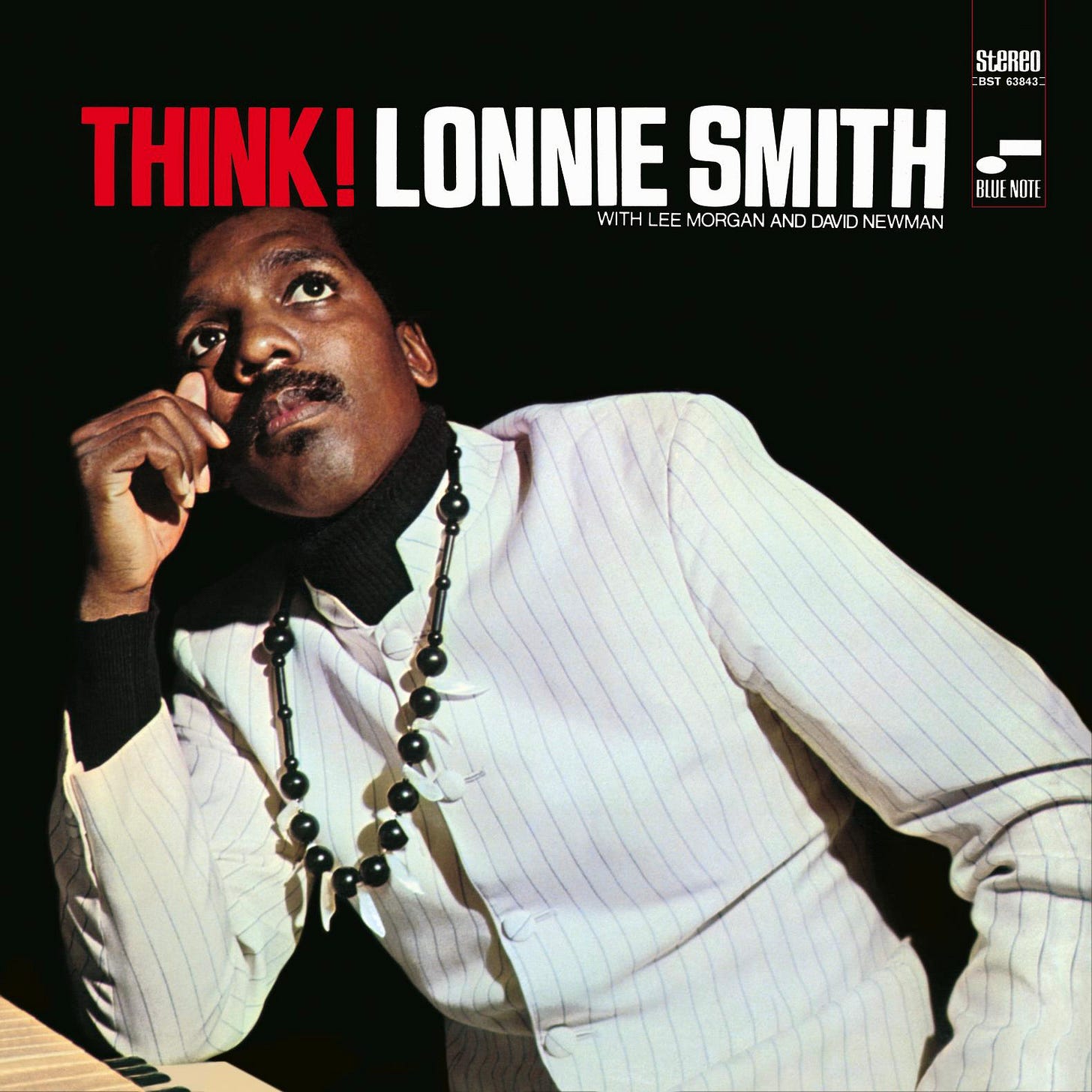

Lonnie Smith, Think!

Smith extends Jimmy Smith’s B3 innovations through modal applications. His left-hand bass lines create counterpoint with right-hand melodic figures. Lee Morgan’s trumpet adds linear precision to Smith’s thick organ textures. David Newman’s tenor saxophone bridges hard bop and soul jazz aesthetics.

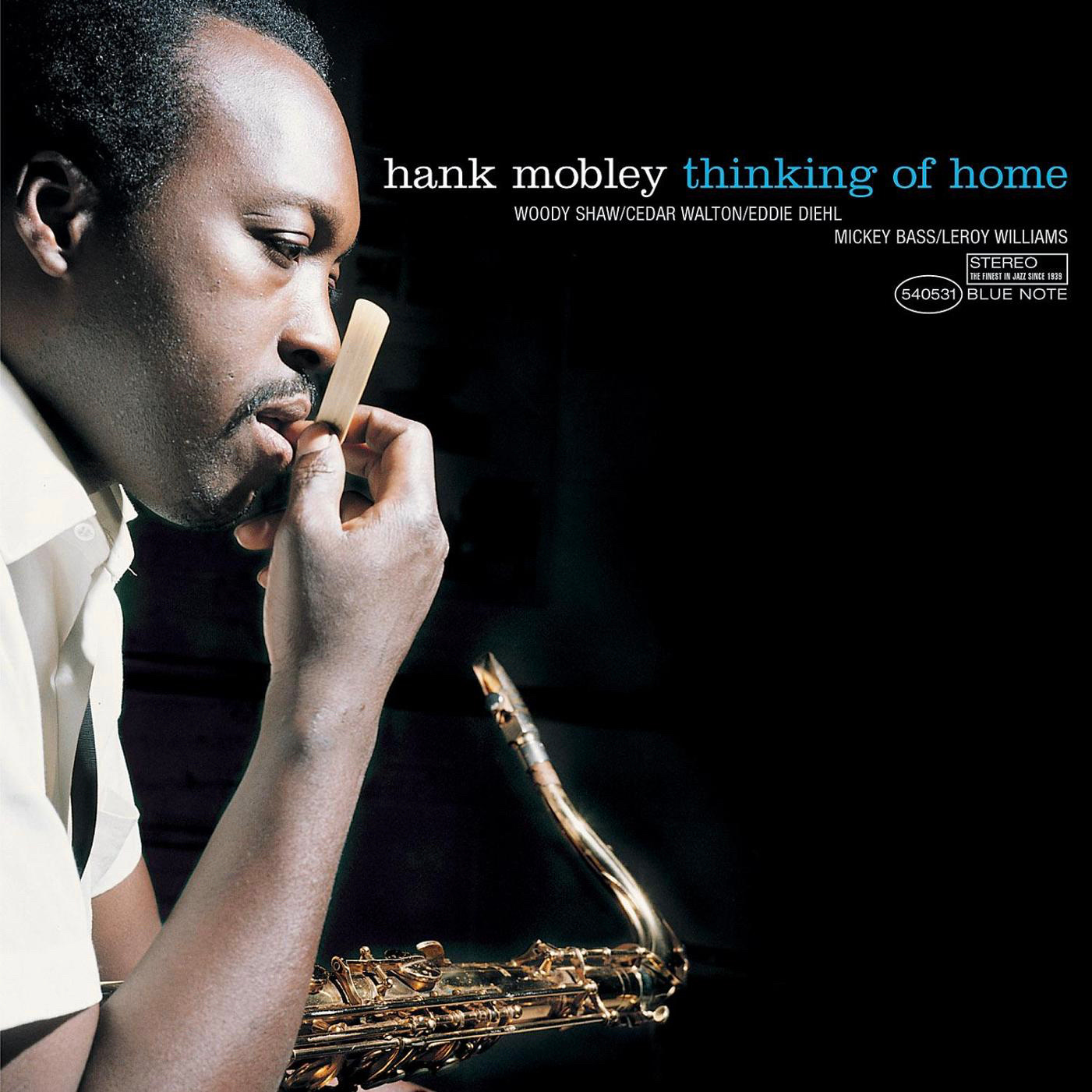

Hank Mobley, Thinking of Home

Mobley’s late-career masterpiece breaks from his earlier hard bop foundations. His tenor saxophone articulation embraces more unrestricted rhythmic concepts while retaining his characteristic warmth. Cedar Walton’s piano flourishes illuminate the harmonic landscape with modern voicings, Eddie Diehl’s guitar introduces unexpected timbral combinations, and Mickey Bass and Leroy Williams construct flexible rhythmic frameworks that shift between straight-ahead time and looser metrics.

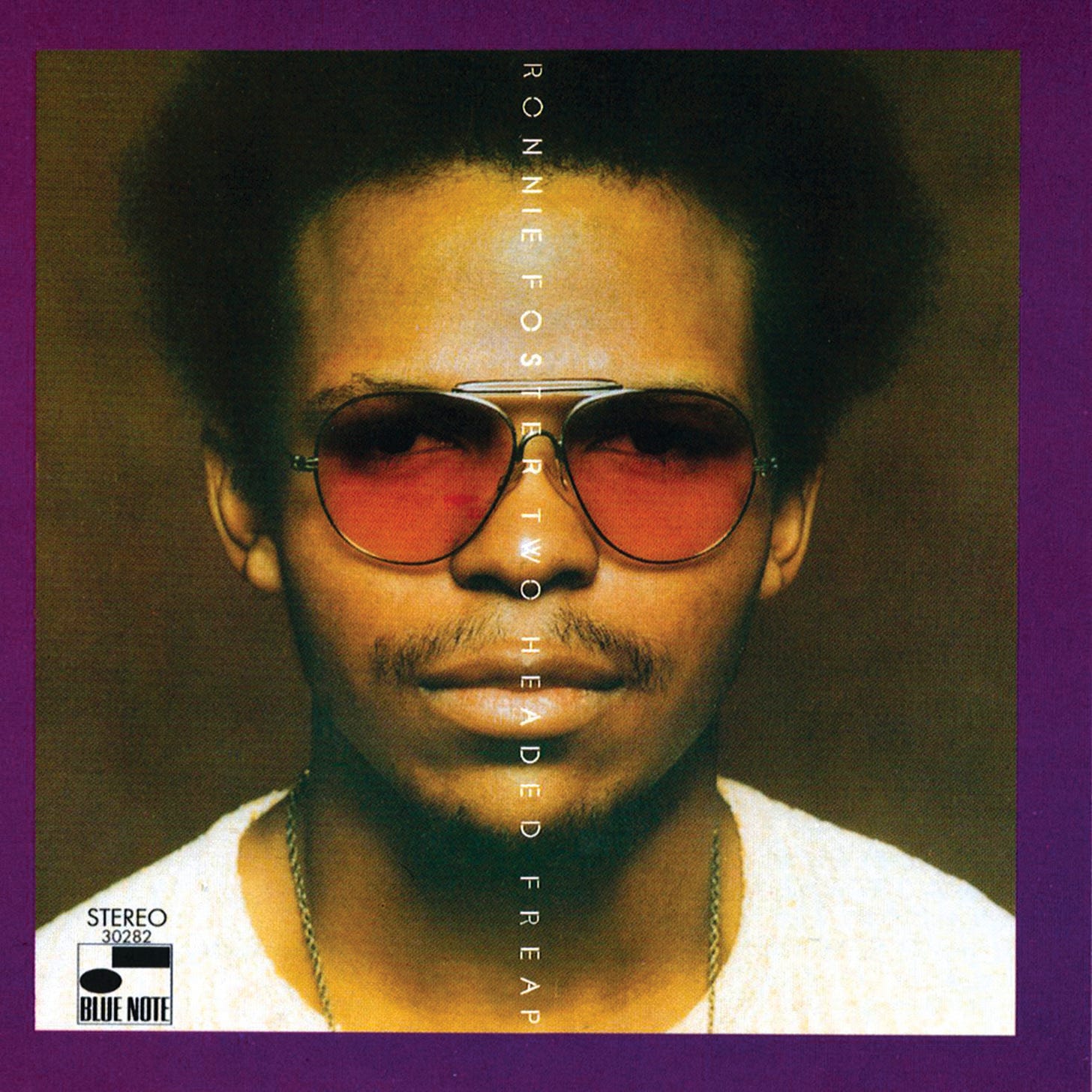

Ronnie Foster, Two Headed Freap

Foster updates the organ trio format through funk influences and electronic effects. His Fender Rhodes work complements traditional Hammond B3 sounds. William Henderson’s guitar adds rhythmic emphasis, while Jimmy Smith’s drums incorporate funk backbeats. “Mystic Brew” became a sample source for subsequent hip-hop productions.

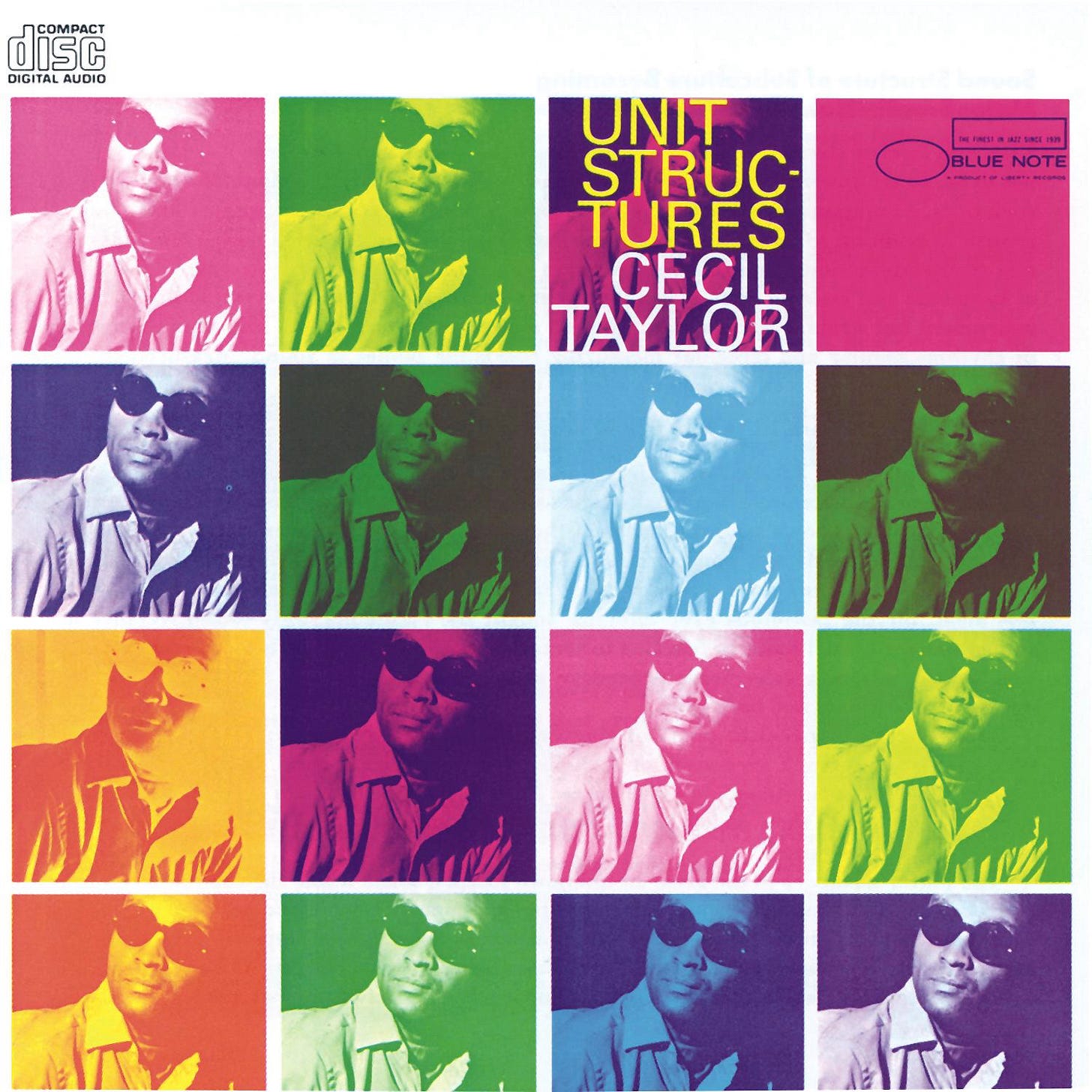

Cecil Taylor, Unit Structures

Taylor’s piano technique redefines the instrument’s possibilities through cluster chords and percussive attacks. The ensemble sections balance freedom with structure by carefully using conducted cues. Eddie Gale and Jimmy Lyons create brass and reed dialogues that mirror Taylor’s intensity. The rhythm section responds to density changes rather than maintaining fixed patterns.

Larry Young, Unity

Young reimagines organ jazz through modal and post-bop approaches. Woody Shaw’s trumpet lines complement Young’s harmonically advanced solos. Joe Henderson’s tenor saxophone adds compositional weight to the ensemble. Elvin Jones’ polyrhythmic drumming pushes the music toward Coltrane-influenced territory.

Bobby McFerrin, The Voice

McFerrin’s solo vocal performances reimagine jazz standards through extended techniques. His interpretations demonstrate multi-layered vocal arrangements without overdubs. Innovative vocal production sprouts through percussion effects and bass lines. The album expands jazz vocabulary through pure vocal expression.

Duke Pearson, Wahoo!

Pearson’s arrangements extend the potential of unusual instrumental combinations. Donald Byrd’s trumpet and James Spaulding’s alto saxophone create a distinctive blend in the front line. Bob Cranshaw’s bass adds rhythmic precision, even supposing Mickey Roker’s drums respond to arrangement dynamics.

Sonny Rollins, Way Out West

Rollins crafts inventive statements in the piano-less trio setting. Ray Brown anchors the harmonic foundation with nimble bass work. Shelly Manne punctuates Rollins’ ideas with responsive drum commentary. Under Rollins’ imaginative treatment, Western songs bloom into complex jazz interpretations.

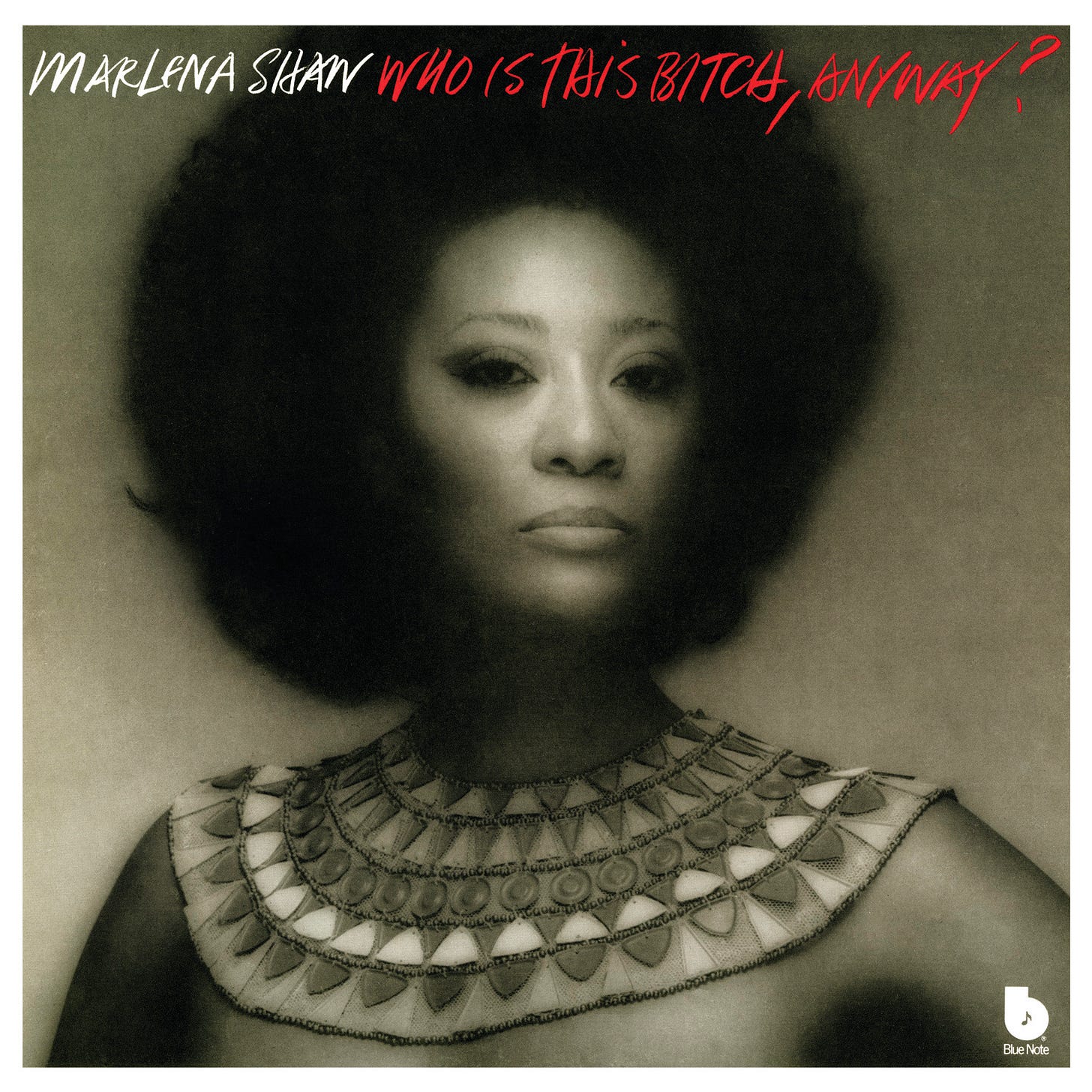

Marlena Shaw, Who Is This Bitch, Anyway?

Shaw combines jazz vocals with social commentary and funk rhythms. Her interpretation of “Feel Like Making Love” reconstructs the standard through contemporary R&B filters. George Bohanon’s horn arrangements add sophisticated jazz harmony to funk-based rhythms. The album bridges multiple Black music traditions while maintaining artistic unity.

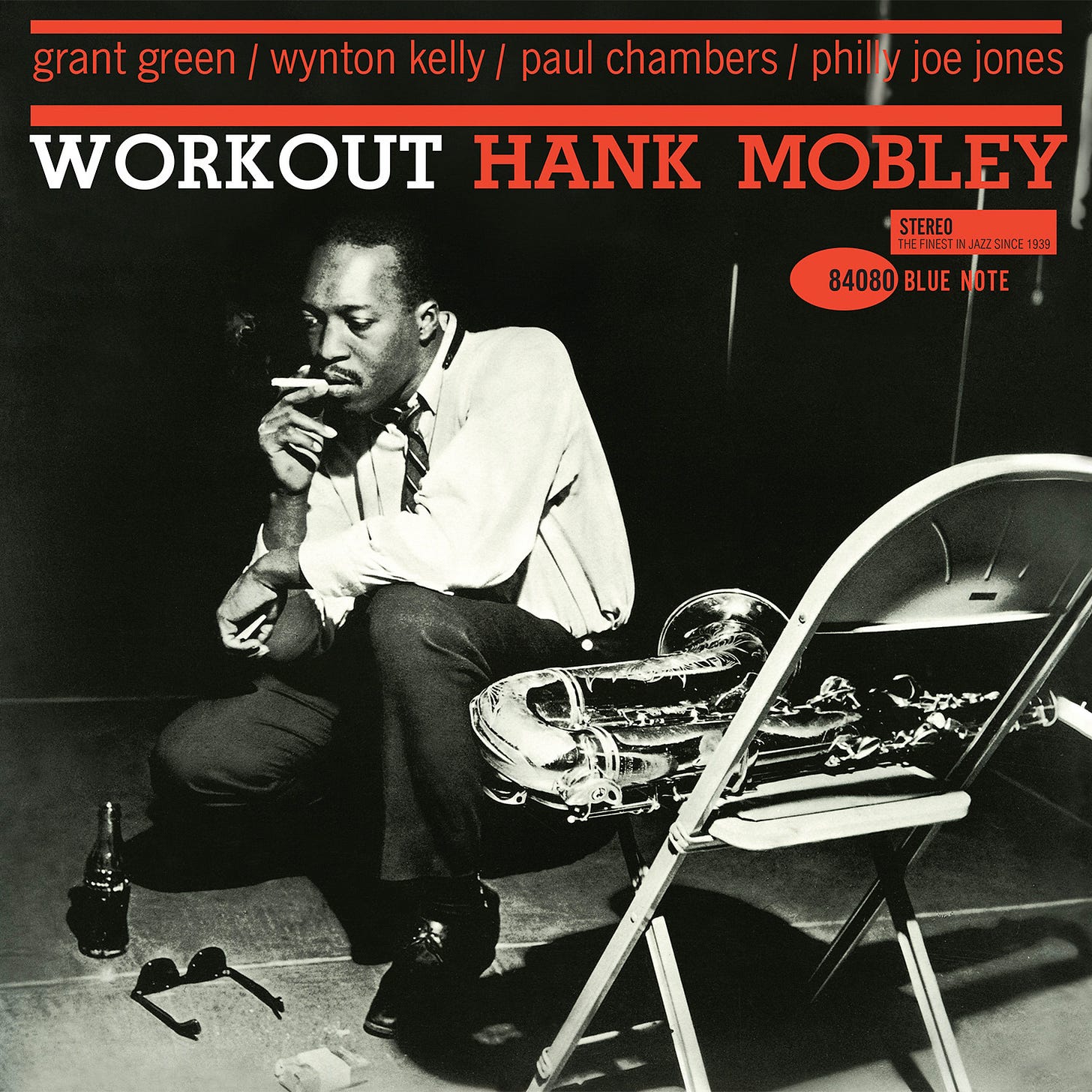

Hank Mobley, Workout

Mobley’s middle-register tenor approach focuses on melodic construction over technical display. Wynton Kelly’s piano adds rhythmic crispness through strategic chord placement. Paul Chambers’ bass walking lines create forward momentum, albeit Grant Green’s guitar comping adds harmonic clarity. “The Best Things in Life Are Free” demonstrates Mobley’s ballad interpretation skills.