DJ Premier & Ransom’s Reinvention and Jung’s Red Book

Two men meet the abyss from opposite ends of history—one through ink and beat breaks, the other through brush and myth.

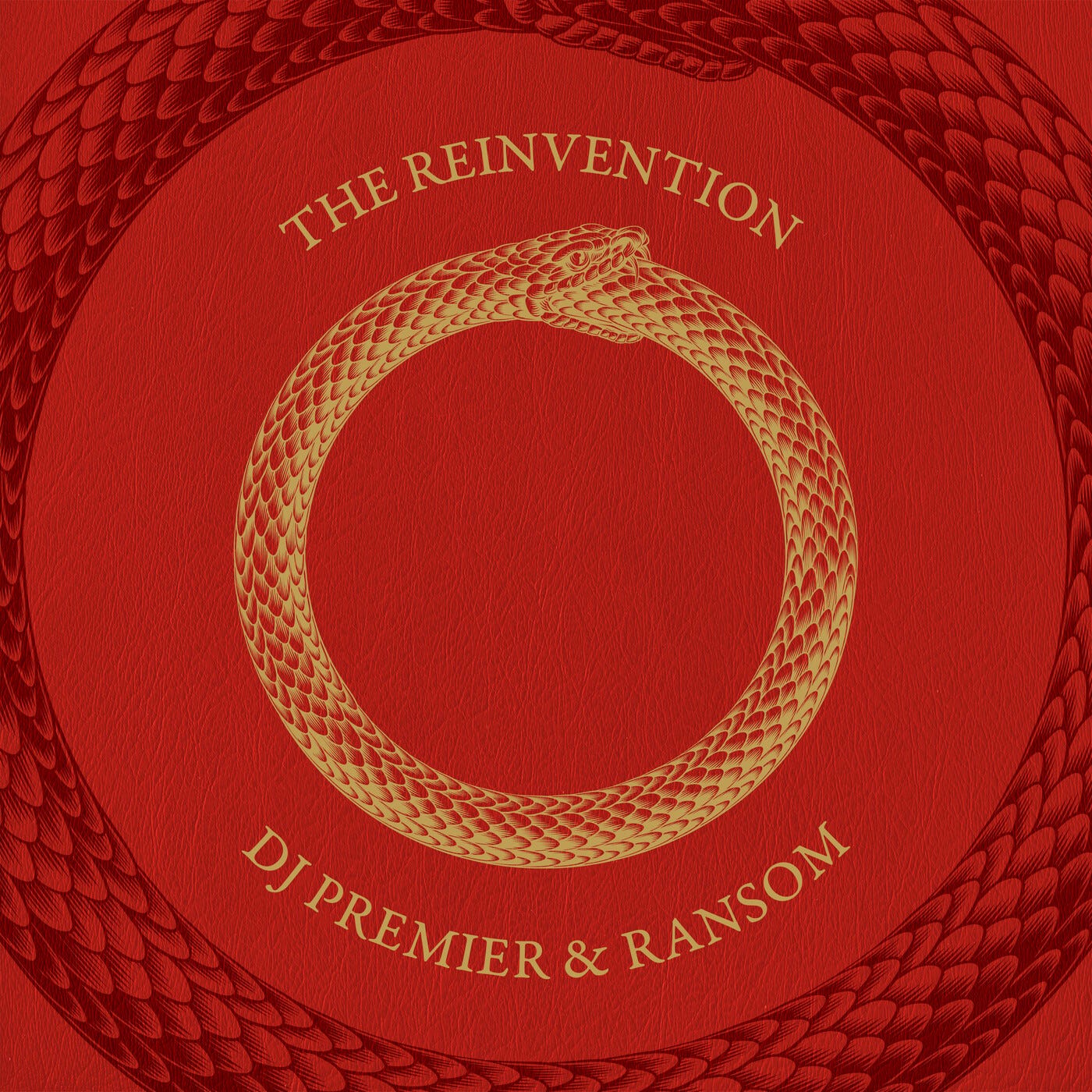

In the autumn of 2025, DJ Premier and Ransom released The Reinvention, a seven‑track project that quickly acquired the gravity of an elder blessing rather than a mere mixtape. Its timing, after years of personal and musical turmoil for both men, invites comparison with another artifact of crisis and rebirth: Carl Gustav Jung’s The Red Book, a secretive, illuminated volume created between 1913 and 1917 in which Jung recorded his psychological “experiments on himself.”

DJ Premier and Ransom enter this collaboration not as newcomers but as artists who have survived their own storms. Ransom has been rapping since 2000, enduring a beef with Joe Budden, a prison sentence, and many years of obscurity before receiving renewed respect in the 2020s. His recent work with Rome Streetz and Conway the Machine proved he could hold his own among rap’s most technical craftsmen. DJ Premier, meanwhile, is a legend whose beats have shaped hip-hop's DNA; yet he, too, has been seeking a new purpose after decades of work. The Reinvention pairing, therefore, reads as a meeting of two master craftsmen at a moment of transformation: one whose fingerprints are masterfully crafted into the DNA of hip‑hop production for three decades, and another who is recognized as one of the best pound‑for‑pound emcees alive (that is now finally getting his just due). The project is short, with only six songs and a Rap Radar interlude, but its aesthetic is rooted in timelessness, a return to craft over melodrama. For both men, this is a ritual.

Jung’s Red Book was also born of crisis. After a fractious split from Sigmund Freud in 1913, Jung retreated from many professional activities and embarked on what he later called his “most difficult experiment.” Between 1913 and 1917, he deliberately evoked fantasies, entered them “as into a drama” and recorded the dialogues and visions in a series of journals known as the Black Books. He confronted figures from his unconscious and refused to let them leave until they had explained their purpose. Although this work looked like madness to outsiders, Jung continued to practice medicine, lecture, and serve in the Swiss Army. He recognized that enlightenment required more than imagining light; one must make the darkness conscious. As he later wrote, “One does not become enlightened by imagining figures of light, but by making the darkness conscious,” and “Everyone has in him something of the criminal, the genius, and the saint.” Wholeness demanded grappling with the inner criminal as well as the inner saint. The Red Book remained unpublished until 2009, but it formed the nucleus of Jung’s later theories and offered a map for those willing to descend into their own underworld.

The Reinvention can be approached as a modern alchemical text following Jung’s model. Ransom’s verses operate like Jung’s dialogues with his unconscious, while DJ Premier’s sample loops function as mandalas of memory. Premo’s drums (though not as punchy and hard-hitting on this record), scratches, and sampling style are among the most recognizable in hip‑hop yet remain inimitable. His loops do not simply provide rhythm. They spin like mandalas—circular patterns Jung used for meditation—around which Ransom’s narratives revolve. Premier’s willingness to ease into his signature sound allows Ransom’s stories to take centre stage, much as Jung’s disciplined calligraphy allowed his inner dialogues to unfold on the crimson pages of the Red Book.

The album’s language provides a psychological map. On “Chaos Is My Ladder,” Ransom confronts his shadow. The title and theme state plainly: “Chaos is my ladder/It’s hard to reach my level/And I don’t regret any of it.” He welcomes disorder because it has been the only way to ascend. In the first verse, he gives us “a view of the grudge, pain, and chaos”—gunshot wounds, corrupt cops, and rough days in court where “trust saves a Braveheart.” His environment is one in which men “die for them whips and chains” and the bloodstains of the drug game mark the graveyards. Yet he refuses to be broken by this ladder. “Made a table out of a broke ladder while most starved,” he raps, turning the emblem of his struggle into a surface upon which to build community. Later, he recounts telling the devil to take a walk, only to hear, “He said it’s better to dance.” This dialogue with the devil echoes Jung’s method of engaging his inner figures rather than banishing them. Ransom’s willingness to converse with chaos and with personified evil, rather than pretending they do not exist, mirrors Jung’s insistence that enlightenment comes from making the darkness conscious.

The second map point, “Forgiveness,” explores individuation through guilt. Ransom starts by shattering his public persona:

“Apparently, I’m not that rapper that y’all thought I was…

I was brought up in envy, I wasn’t taught to love.”

He admits he was a thief and killer because “your honor was expendable when you said it before a judge.” He acknowledges being “in debt to the Lord above” while carrying “hell’s fire” in his chest. He makes a plea: “Mama please forgive us… You niggas in the streets, but homie the streets is in us.” The guilt here is not abstract; it is the guilt of a son whose mother still thinks he is at risk of violence and incarceration, and it is the guilt of a man who has survived where others did not. By confessing his envy, his violence, and his spiritual debt, Ransom begins the individuation process that Jung described: integrating the shadow elements of the self rather than repressing them. In Two Essays on Analytical Psychology, Jung wrote that wholeness requires accepting that each of us carries a criminal and a saint. Ransom voices this recognition when he raps that he sent ten keys to Philadelphia while labels sent A&R reps, and yet the streets are still within him. His refusal to make his threats public—“I don’t make my threats public/Don’t forget much, think History was my best subject”—shows a man who has learned discipline and is integrating his past into a more responsible self. The track’s movement from confession to forgiveness echoes Jung’s process of active imagination: he brings his crimes and guilt into dialogue with his conscience and, in doing so, finds a path toward wholeness.

“Survivor’s Remorse” serves as the death of the false self: “Survivors remorse, make it out or you’ll die in this war/Streets got your life in a vice grip… You’re feeling guilty, they ain’t make it out the eye of the storm.” Success is haunted by the faces of friends who were killed. Ransom’s narrative about his friend Ra is heartbreakingly specific. He orders Ra to keep his eyes on the porch and be ready to “fire the torch,” knowing he would die for the cause. Ra is portrayed as a quiet intellectual whose dreams of playing basketball professionally are undermined by expectations to hustle. When Ra tries to leave for an overseas career, he is murdered the night before his flight. The story functions like one of Jung’s visions: a figure appears with a message about the consequences of staying in the “false self” of street life. In the Red Book, Jung refused to let such figures depart until he understood their meaning. Similarly, Ransom refuses to let Ra’s death be just another tragedy; he turns it into a lesson. The death of the false self here is not just Ra’s literal death; it is also Ransom’s shedding of his old persona. The guilt he feels for surviving is a catalyst, pushing him to embrace vulnerability and to reject the notion that success requires ignoring the casualties left behind. In doing so, he approximates Jung’s assertion that one must integrate the parts of the self that elicit shame and guilt to achieve psychological wholeness.

The title track, “Reinvention,” represents the return from the underworld with a new moral architecture. Ransom opens by asking his mother if she can remember him before dementia: “She don’t even know my name or my age… all that shit that we overcame I would hold that pain in the center of my soul.” He confesses that, on some days, he resents her and is ashamed of his temper. Watching a parent’s mind disintegrate, he realizes that birthdays and Septembers no longer mean anything to her. The song then widens to include his brother, his sister, and the old crew. “My older brother, I know I’m supposed to avenge you… It would’ve been easy when my heart was cold as December,” he admits, recalling a time when he smoked rock in a Sentra and sold dope. He names the scars that the street handed him and declares that he never surrendered. The final lines (“Now witness my growth, I give you all my reinvention”) are his proclamation that he has arisen from the underworld with new architecture. He no longer seeks vengeance or validation; instead, he offers his transformation to the listener as evidence that survival can become sacred work. Jung wrote that the years of inner images recorded in the Red Book were “the most important time of my life,” and that everything later was merely elaboration. Likewise, Ransom implies that the reinvention documented here—his confrontation with chaos, his confession of guilt, his mourning of friends—is the foundation upon which all future music and morality will be built.

Placing The Reinvention as a modern alchemical text clarifies how Black self‑analysis has always been both survival work and sacred work. In alchemy, base metals are transmuted into gold through a series of purifications; in Jung’s psychology, the leaden unconscious is transformed through active imagination. Ransom’s lyrics transmute trauma into symbol. His description of chaotic streets—gunshots, corrupt cops, and broken ladders—confronts the raw lead. His pleas for forgiveness and confessions of guilt refine that material. His survivor’s remorse burns away the false self. As mentioned in the title track earlier, he has distilled a new gold: a morality that is tender toward his mother, accountable to his brother and children, and honest about his past. Just as Jung drew ornate mandalas during his descent, Premier cuts records into loops that spin like prayer wheels, holding memory in place while Ransom inscribes meaning. The loops sample soul and jazz to create a nostalgic, timeless atmosphere that invites us into a ritual space. Their collaboration is thus a sonic monastery in which street corners replace cloisters, but the work of self‑examination remains the same.

Reading The Reinvention alongside The Red Book also underscores the continuity between Jungian introspection and Black expressive traditions. Where Jung wrote out dialogues with mythic figures like Salome, Ransom converses with devils, dead friends, and his own younger self. Where Jung painted mandalas to orient his psyche, Premier constructs beat loops that anchor memories and open portals. Both projects reject the idea that wholeness can be achieved by pretending to be pure. They insist that healing requires acknowledging one’s complicity in violence and one’s capacity for grace. When Ransom declares, “Now witness my growth, I give you all my reinvention,” his statement resonates with Jung’s recognition that everyone harbors a criminal, a genius, and a saint. The album thus becomes a Black Jungian quest, a work of hip‑hop that builds cathedrals from chaos, where the sacred evolves not by fleeing the streets but by turning them into sites of philosophy and prayer.