Doechii and the Misogynoir Behind Industry Plant Talk

“Industry plant” sounds like music discourse until you watch who it gets used on and how. Doechii's record turns the accusation into a mirror and leaves it there.

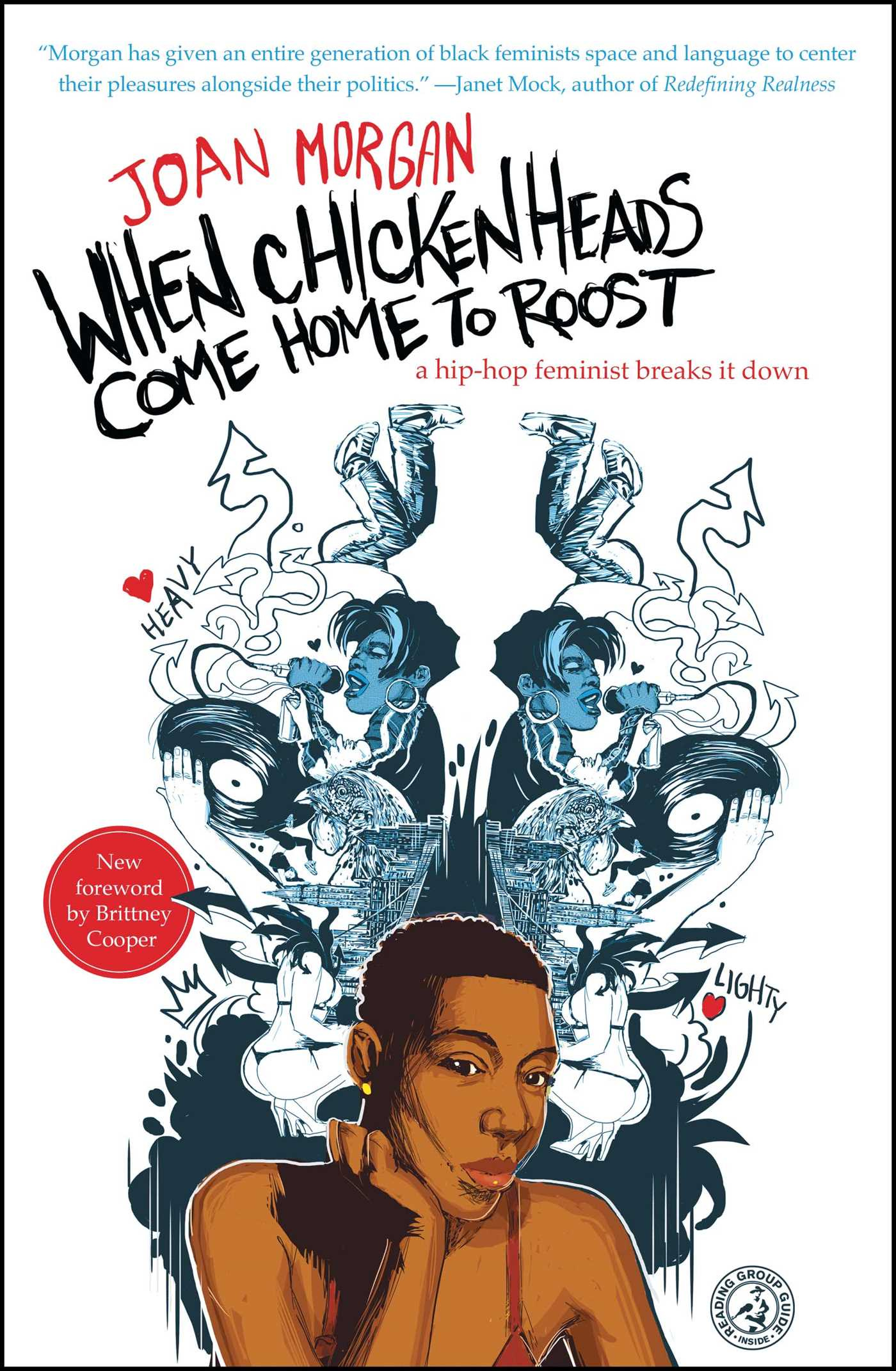

Joan Morgan published When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost in 1999 with a confession most feminists at the time wouldn’t touch. She needed permission to name contradiction without apologizing for it. “I needed a feminism brave enough to fuck with the grays,” she wrote. The grays being: how you can love hip-hop and resent its violence against you in the same breath. How a Black woman can demand accountability from Black men and still refuse to hand her brothers to a system that will devour them. How the wounds inflicted by sexism don’t disappear just because racism inflicted worse ones first. Morgan wanted the right to say all of it, all at once, without begging absolution from anyone.

Twenty-six years later, Doechii dropped “girl, get up.” on the day before New Year’s Eve and demonstrated that the permission Morgan carved out still costs something. The song responds to months of accusations that the Tampa rapper is an “industry plant,” that she’s on drugs, that her Grammy win for Best Rap Album was unearned. The charges have circulated on livestreams, comment sections, and gossip loops since at least May, when Adin Ross went on a viral tirade calling her “unintelligent,” “entitled,” “talentless,” and several variations of bitch after the Met Gala debacle. Even before that, Kendrick Lamar co-signed her as “the hardest out” in the aftermath of the rap beef that got the male Drake groupies scrambling, and won a Grammy for Best Rap Album. Rather than let the noise drift, Doechii committed the offense of answering it: “All that industry plant shit wack, I see it on the blogs, I see you in the chats, you suck every rap nigga dick from the back, but what’s the agenda when the it girl Black?”

That question, “What’s the agenda when the it girl Black?,” pins down what the discourse evades. Misogynoir is the word for what she’s describing. You know, the term Moya Bailey coined in 2010 to name the specific contempt Black women face at the intersection of anti-Blackness and misogyny. It’s not racism plus sexism stacked like bricks. It’s a third compound, corrosive in its own right, and it operates through mechanisms that sound neutral: skepticism, concern, even protection. The accusation that a successful Black woman must be a plant, a fraud, a puppet, or a charity case is one such mechanism. It reexamines her labor as someone else’s investment. It strips her of authorship. It says: we know you didn’t do that yourself, so name who did.

The drug rumor runs a different circuit. “Y’all wanna believe I’m on drugs and forsaken/They won’t credit me, so they blame it on Satan.” Drug talk invites contempt and licenses dismissal. If she’s strung out, then her talent is suspect, her work ethic is borrowed time, and her body is public property available for moral inspection. It’s respectability’s backstage pass. Doesn’t matter whether evidence exists. The rumor alone creates permission to withhold regard.

Morgan understood these tactics a quarter-century ago. In her chapter “from fly-girls to bitches and hos,” she asked Black women to use hip-hop as “the mirror in which we can see ourselves.” She knew the reflection would be brutal. “And there’s nothing like spending time in the locker room,” she wrote, “to bring sistas face-to-face with the ways we straight-up play ourselves.” The locker room for Morgan was the music itself—the place where young Black men said the ugliest truths about how they saw Black women out loud. She didn’t want access to scold. She wanted access to understand: “I need to know why they are so angry at me. Why is disrespecting me one of the few things that make them feel like men?”

Last year, the locker room moved. It’s the livestream, the reaction video, the comment thread, the group chat screenshot, the quote-tweet that decides who deserves benefit of doubt. The contempt still travels, but it recruits faster now, and the audience participates in real time. Ross’s rant was broadcast. His follow-up diss track with 6ix9ine and Cuffem was clipped and circulated within hours. The insults compound through repetition, and the repetition creates consensus. By the time people hear Doechii’s name, the contrive is already set: prove you belong here, or shut up.

What Morgan grasped (what still applies) is that Black women who refuse that assignment get rewritten. Her chapter on the STRONGBLACKWOMAN lays out the bind. The myth descends from slavery, when white enslavers needed to believe Black women could withstand anything: labor, rape, the theft of children, isolation, violence. “The STRONGBLACKWOMAN was born in the antebellum South,” Morgan wrote. “She had a white step-sister named SOUTHERNBELLE.” The Belle got fragility and protection. The SBW got endurance and zero complaint. Both myths served the same patriarch.

The contemporary version of that bind is the pressure to absorb disrespect and keep producing. Stay cute. Keep moving. Don’t dignify the slander. Prove you earned air. Morgan eventually retired from being a STRONGBLACKWOMAN—she called it an act of salvation—because the role was leaking her dry. “I wanted the same for my daughter,” she wrote. “I wanted her to know that her legacy is a willingness to fight, to play hard and win, and find love in everything she does.” That’s different from proving you can take a punch. That’s refusing to audition for people who already decided you failed.

Doechii’s “girl, get up.” does something riskier than endurance. It names the move being used against her and refuses to convert the naming into gratitude or reassurance. She doesn’t beg the audience to believe her. She clocks the behavior: you’re comfortable disrespecting me, and the comfort is the point. “These niggas misogynistic, I’ll address it on the album. For now, let’s sink into the fact that hate doesn’t make you powerful.”

Lateral policing complicates the picture. Morgan’s chapter on “chickenhead envy” tracked how Black women weaponize respectability against each other, how desire and resentment coexist, how the economics of attention pit women against women when access to resources flows through men. She wasn’t interested in flattening women into villains. She was interested in naming what scarcity and proximity do to solidarity: “Any sista whose standards won’t allow her to settle for anything less that’s going to end up with that finished product.” The envy was real, but so was the context that produced it.

The Doechii discourse has recruited women too. Some of the loudest skepticism about her rise comes from women who perceive her success as unearned, her visibility as suspicious, her self-confidence as arrogance. Part of that is the scarcity math Morgan described: if there’s only room for one or two Black women rappers at a time, then her seat threatens mine, or threatens the seat I’m rooting for. Part of it is something uglier—a borrowed contempt, a willingness to punish Black women for winning too loudly without asking anyone’s permission first.

Morgan didn’t let love become a gag order on critique, and she didn’t let critique become an excuse for cruelty. “For me,” she wrote, “Black-on-Black love is essential to the survival of both. We have come to a point in our history, however, when Black-on-Black love—a love that’s survived slavery, lynching, segregation, poverty, and racism—is in serious danger.” The danger is the appetite for humiliation dressed as analysis.

Doechii forced a recognition by naming the tactic publicly. When the it girl is Black, people will reach for any tool that restores doubt. Industry plant. Drug addict. Satanist. Manufactured. The accusations don’t require evidence because they’re not really about evidence. They’re about reinstating a hierarchy where Black women’s success always carries an asterisk. As for Joe Budden, don’t worry. We’ll get back to you at a different time since you don’t want to “talk about this subject.” What changes when she names that move is the distribution of discomfort. Now the audience has to decide whether they enjoy the contempt or admit it’s contempt. The mirror stays up. The reflection doesn’t soften into anything redemptive. She doesn’t offer forgiveness. She offers: I see what you’re doing, and so does everyone watching you do it.

That’s a boundary drawn in public, with receipts.

ohhh this was good, per usual. I really appreciate Doechii making a song and addressing it how she's decided to do, because what people hate the most is when you respond to the wild shit they're saying. also, I need to get this book! thank you for this!

Necessary commentary!! Thanks for publishing this.