Doechii’s School of Hip Hop Becomes Theater Without Losing Its Bite

Doechii's School of Hip Hop performance unfolded as she’d rehearsed for a world where control is currency. Every switch‑up showed how fast she can reshape a room.

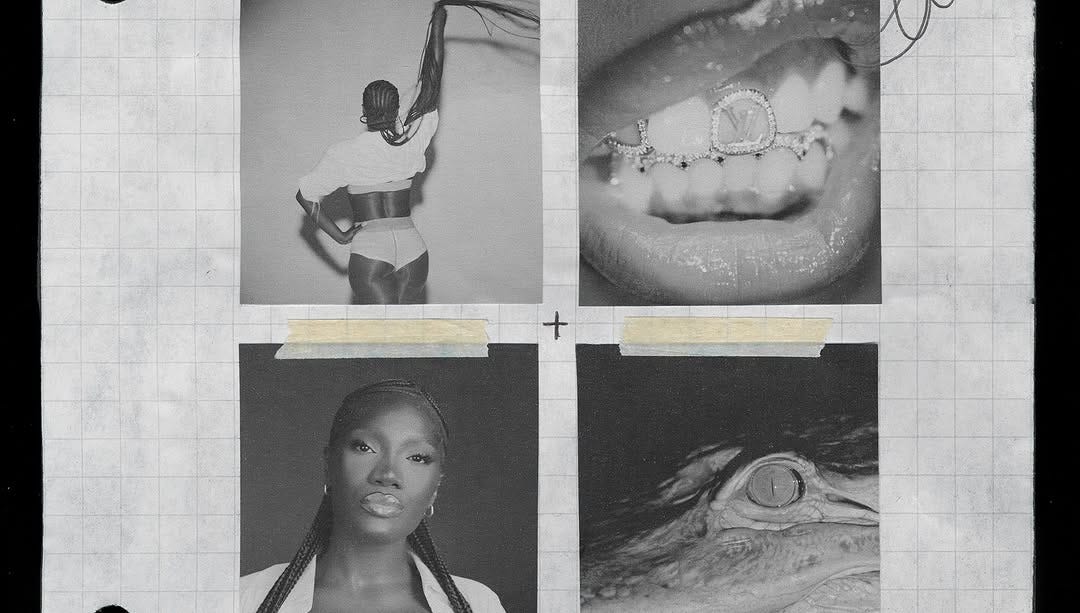

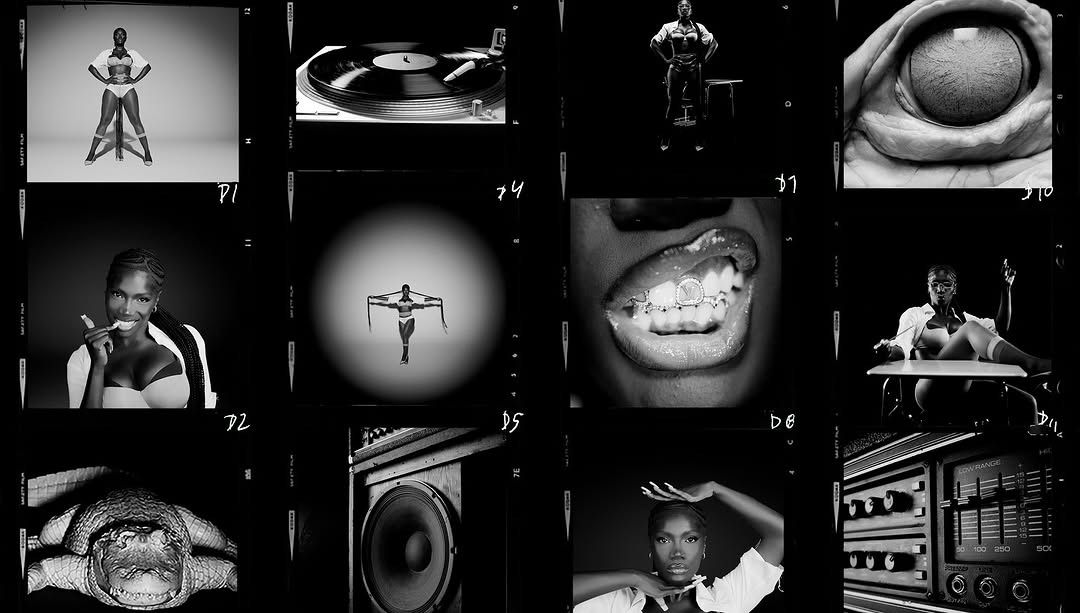

The first bell rang and a two-story boombox split down the middle. Its speaker cones, already pulsing with blue light, rotated like turntable platters. A record inside the boombox hinged open to reveal DJ Miss Milan, headphones draped around her neck and hands poised over the mixer. A classroom desk rolled forward on a robotic platform, carrying a young woman dressed in a gray pinstriped pantsuit with a cone-cup bustier. She perched on the chair and rapped into a wireless microphone. She called the song “Stanka Pooh,” a sour-sweet introduction from her Grammy-winning mixtape Alligator Bites Never Heal. Each bounce and backbend punctuated the bars; halfway through, she stood on the desk, thrusting her backside toward the audience and turning a simple orientation phrase into a joke about conjunctions. Behind her, nine dancers in matching uniforms pushed desks into different formations and climbed the boombox’s stairs and slides, signalling that class was in session.

Before the opening notes ended, the Tampa-born rapper slid from teacher to student and into the first lesson. “Bullfrog,” a head-nodding track built around Wu-Tang Clan’s “C.R.E.A.M.,” hit like a shot of adrenaline; she glided across the stage as the lights shifted from blue to blood red. Without stopping, she pivoted into “Boiled Peanuts,” where a JAY-Z “Can I Live” sample hovered beneath her verses. These songs, grouped as Bars in her syllabus, functioned less like a setlist than a demonstration of lineage. When she nodded to the Bravehearts and Nas by weaving the cadence of “Oochie Wally” into “Spookie Coochie” later in the show, it felt like another footnote in her history lesson rather than trivia. She had studied Doug E. Fresh’s “La Di Da Di” and Mike Jones’s “Still Tippin’” enough to tease each without derailing the groove. That practice of citing sources continued across the curriculum, establishing her as a scholar who knows exactly where her work sits within rap’s archive.

The second lesson, Flow, emphasized control over tempo and cadence. “Nissan Altima” served as the anchor. She sprinted up one of the boombox’s slides and down the other while spitting double-time bars and interjecting quick jokes about lost car keys, flashing a grin when the crowd responded in kind. Onstage cameras captured her hair whipping as she descended the slide, projecting the image on side panels so that fans at the back could follow each pivot. At one point, Miss Milan cut the beat entirely for a freestyle over Beyoncé’s “America Has a Problem,” and Doechii rode the silence with an a cappella verse that drew audible gasps. She followed with a snippet of Trina’s “Pull Over,” using the interlude to twerk across the boombox’s top platform. This ability to modulate breath and swing across rhythms, from Southern bounce to East Coast boom-bap to Houston chop-and-screw, demonstrated that flow is an elastic concept rather than a singular pace.

Experimentation, the third lesson, allowed her to stretch genre boundaries. “Alter Ego,” originally a duet with JT of City Girls, became a solo exercise in switching characters; she rapped both parts and gestured playfully to the pre-recorded vocals as if engaged in call-and-response with herself. A voguing clip featuring ballroom commentators played on the jumbotron before the song, leading her twin sisters and the rest of the dancers into ballroom-inspired choreography with dips and catwalk poses. “Persuasive,” a house-driven track, bled into a brief interpolation of Beyoncé’s “Blow” and a Charli XCX “360” tease, and she maintained the momentum by riding the automated desk around the stage during “Slide,” waving to different sections of the crowd. This segment delineated genre-blurring not as a gimmick but as a cornerstone of her curriculum—experiment, she seemed to say, and find new ways to connect old ideas.

Scratching time belonged to DJ Miss Milan. After Doechii introduced her at the end of “Boiled Peanuts,” Milan stepped out from the record-player cavity and took center stage with a crate of vinyl. She kept the beat between songs by flicking crossfaders and scratching at 45-rpm pace, then slowed down to demonstrate the fundamentals of turntablism. During “Spookie Coochie,” she and Doechii traded roles: Milan acted out the lover in the song’s mini-play while Doechii swapped bars and smirked at her own innuendo. Their chemistry underscored that the School of Hip Hop is not a solo project; the DJ’s crossfades were more like tonal shifts, moving from the eerie glow of orange and red lights for “Spookie Coochie” into deep crimson for “Nosebleeds” and back to cool violet for “Slide.”

Detention, a single-song lesson, arrived when the classroom door slammed shut and a chalkboard with giant letters reading “DETENTION” flashed on the screens. “Nosebleeds,” written after her Grammy win, repurposed Kanye West’s 2005 Best Rap Album acceptance speech as a hook: “Errbody wanted to know what Doechii would do if she didn’t win… I guess we’ll never know.” She strutted across the stage, flipping a ponytail and pausing to pose with each dancer. The result was a moment of comic discipline—the teacher issuing a playful punishment for her own success. At the side of the stage, Miss Milan scratched West’s original cadence as though to underline the reference; the dancers bounced like they were rewriting a grammar lesson.

Sex Ed transformed the classroom into a locker room. A video clip played before the lesson showed Doechii as a health teacher demonstrating how to put a condom on a banana while warning, “Make sure it’s the right size.” When the stage lights came back up, she invited a few audience members to sit at desks lined up along the catwalk for “Crazy” and crawled across the furniture, giving one fan a lap dance. Her body language fluctuated between camp and sincerity: she lit cigarettes during “Stressed” and “Death Roll,” using the smoke as a prop to punctuate lines about anxiety and addiction, and then stomped in heavy boots during “Boom Bap” and “GTFO,” songs built on aggression and frustration. The rock-leaning version of “Anxiety,” with a heavy guitar substituting the original sample, turned the stage into a headbanger’s playground, while the viral TikTok dance for the song briefly transformed the pit into a synchronized drill. In each case, she remained in full control of her breathing and cadence, a reminder that theatrics never compromised her technical execution.

Wordplay, the seventh lesson, paired technical dexterity with physical flexibility. On “Catfish,” she literally bent over backwards while nailing her flow, and on “Swamp Bitches,” she chanted in unison with the audience as the word “BITCHES” flashed across the screens. She referenced Crime Mob’s “Knuck If You Buck” in “GTFO,” making the call-and-response chorus feel like a cipher rather than a recital. These songs doubled as drills for the crowd: shout the hook, bend with the beat, engage your core as if you were part of the troupe. Her twins mirrored her movements on either side, reinforcing the idea that language and movement are intertwined, that a punchline can be a hip thrust as much as a bar.

As the lights dimmed and the stage hushed, a subtitle on the screen read “The Art of Storytelling.” Doechii reappeared at the top of the boombox’s ladder, spotlight isolating her silhouette against a dark backdrop. “Denial Is a River” unfolded like a miniature play, with Miss Milan playing the ex-lover character, responding in real time to Doechii’s verses. When she delivered the breathing exercise at the end of the track, the entire arena exhaled with her. The instrumental slid seamlessly into Tyler, the Creator’s “Balloon,” and she stomped and screamed at the end of her verse, then calmed the energy to request that everyone raise their phones for “Wait.” As she sang, she transitioned into Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature,” sliding between the two melodies so fluidly that the boundary vanished. In this moment, she recast a pop standard as part of her syllabus, using the interpolation to illustrate how rap interacts with R&B and soul and to show that she can inhabit other legacies without losing her voice.

The final lesson, titled “You,” turned the attention back to the audience. After a video told viewers to remember who they are and what they’ve learned, she rolled across the stage on her desk once more, this time to the outro of Alligator Bites Never Heal. She gave individual shoutouts to her DJ, her dancers, the stagehands, and even the security workers who had helped keep fans safe. She asked the crowd to turn off their phones and hold hands before the last chorus. Without fanfare, she left the stage, returned for a brief reprise of “Nissan Altima” in some cities (other shows she performed that song early on the set), and then vanished behind the boombox. The screen projected the words “Class dismissed” as the stage went dark.

The interplay with the crowd was constant yet tightly controlled. Early in the run, she paused during “Boom Bap” to ensure that a fan who fell over was okay, even instructing the camera crew to keep the person visible until they gave a thumbs-up. In Dallas, she shouted, “Where my gays at?!” and a wave of cheers responded. She repeatedly shouted out weed smokers during “Persuasive,” joking about smelling the finest kush wafting from the pit. But she never relinquished command; she directed call-and-response chants, cued the viral “Anxiety” dance, and admonished the audience to pay attention to her lessons. By the time she rolled across the stage for the closing credits, the crowd had moved through a rigorous curriculum without ever being lectured.

Throughout the tour, costuming reinforced the academic conceit while allowing for constant reinvention. At Lollapalooza, she wore a series of DSquared2 ensembles: an ultra-cropped blazer and cut-off micro-shorts folded over at the waist, and later a semi-sheer lace bra with a pleated denim mini skirt. For the Glastonbury stop she leaned into British academic codes with custom Vivienne Westwood pieces: a pinstripe micro-mini skirt inspired by the label’s 1994 “Café Society” collection, paired with a plunging bra and crystallized pasties resembling the Westwood orb; she accessorized with spectacles, over-the-knee socks and Bondage boots, and later changed into a multi-colored bodysuit topped with a pink bicorne hat. In Boston, she wore the gray pinstripe suit with gold cones under the jacket, evoking Madonna’s Jean Paul Gaultier bustier. The outfits constructed her as a teacher but also as a style chameleon, italicizing the idea that hip-hop education encompasses visual presentation as much as lyrical craft.

Her dancers, including her twin sisters, executed synchronized routines that mirrored her flows, while Miss Milan scratched and played supporting characters with equal flair. The lesson plan’s closing message, delivered on screen before the final song, read “You are exactly who you need to be.” It’s an affirmation and summary: within her theater of hip-hop, the audience was a co-conspirator, learning to recognize the references and appreciate the craft without being taught how to listen. There was no sentimental curtain speech, no extended goodbye—just a bell, a dismissal, and a sense that everyone had graduated.