Five 2010 Rap Albums About Prison, Legacy and Moving Forward

Veteran West Coast ice‑cold bars, Southern trap appeals, and indie‑rap experiments all collided in the same strange year.

2010 is remembered for the obvious landmarks—blockbuster debuts, canonized “classics,” the albums everyone has already argued to death—but rap that year was way messier and more interesting than the usual shortlist suggests. This series on Five 2010 Rap Albums dives into the records that sat just outside the spotlight: a locked‑up superstar testing his fanbase, a posthumous Texas soul sermon, an OG West Coast veteran redefining what “I am the West” even means, a trap kingpin turning court dates into concept, and an indie/underground project quietly sketching out a different future. Taken together, they show how much of the decade’s sound was already taking shape in these so‑called side notes. They’re not the albums that dominated the charts or the thinkpieces—but they’re the ones that still feel strangely alive when you put them on now.

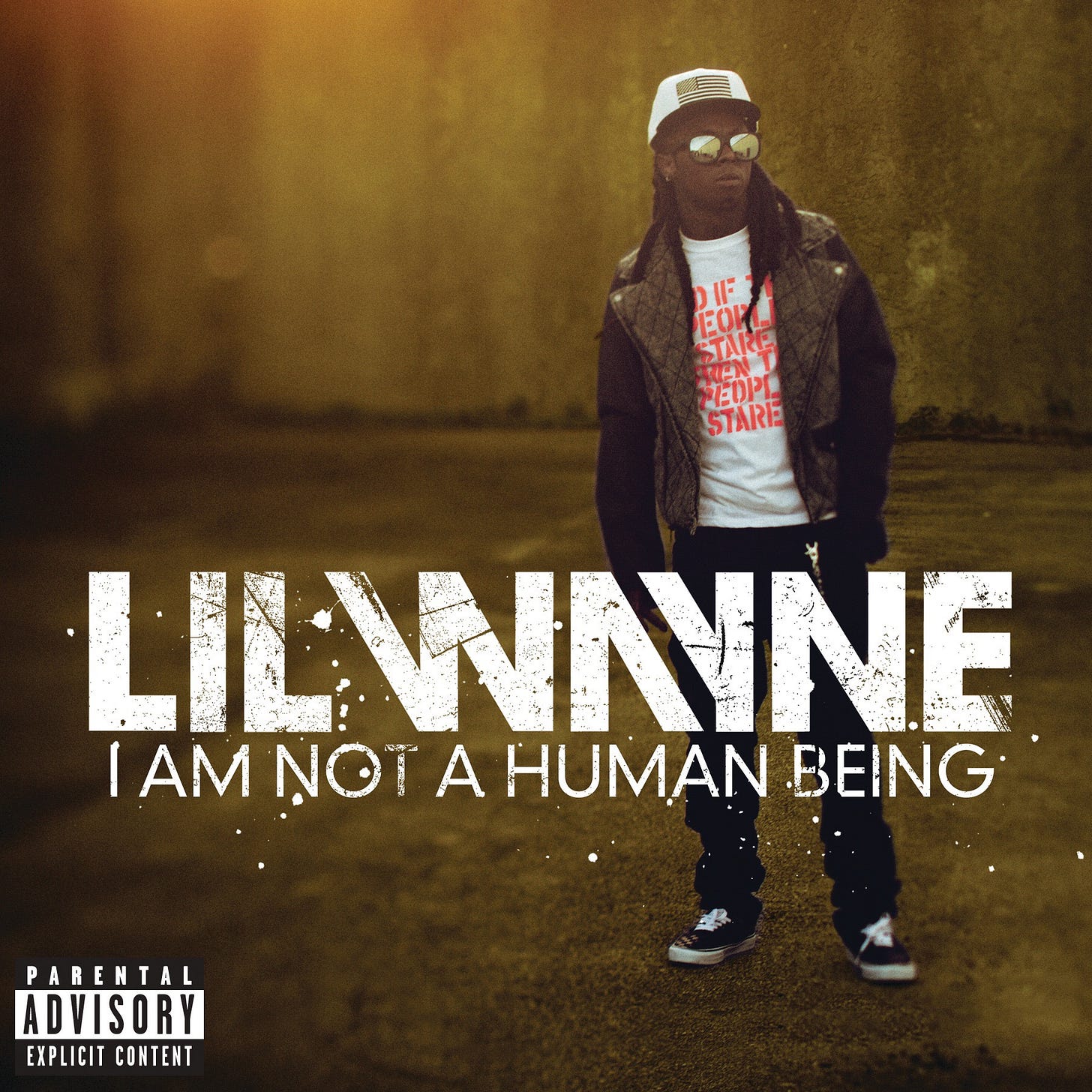

Lil Wayne, I Am Not a Human Being

You get the feeling this is the album Lil Wayne put out to check whether his fans would stay with him even while he was gone—whether they’d keep supporting him while he was locked up. That’s the impression you get the more you listen. The whole world already knows he was in prison when this came out, and everything here was recorded before he went in. Wayne has always been ridiculously prolific, but it’s clear these tracks were made around the same time as, or even before, Young Money’s We Are Young Money and his rock‑leaning album Rebirth. For example, if bonus tracks like “YM Banger” and “YM Salute”, or even the title track itself, had been slipped onto Rebirth, they wouldn’t feel out of place at all—especially since “I Am Not a Human Being” is produced by DJ Infamous, who helped define the sound of that record.

Listening more closely, some of this actually feels more like a continuation of Tha Carter II than of We Are Young Money or Rebirth. On the opening track “Gonorrhea”, one of the most striking lines is that infamous couplet about life being a “bitch” and Wayne “fucking the world,” it’s the kind of over‑the‑top, toxic bravado only he could sell. Later, on “Bill Gates”, over a grand Boi‑1da beat (the same producer who worked with Noah “40” Shebib on Drake’s Thank Me Later), he keeps circling back to the idea that “life is a bitch, but I appreciate her,” turning the same image over and over in his head. Even giving the first song a title as ugly as “Gonorrhea” seems like an extension of that “life is a bitch” worldview—following the logic through to something diseased and uncomfortable. And then there’s Drake. Wayne and Drake appear together four times here, and their chemistry is easily at its sharpest on “Right Above It.” Their back‑and‑forth is so natural that you can honestly imagine them carrying a full‑on duo album someday. On that track, Wayne pushes the “life is a bitch” line even further, flipping it into “life is a beach, I’m just playin’ in the sand,” turning nihilism into a sun‑dazed flex.

Back on Tha Carter II, Wayne seemed determined to put himself on the same level as Nas—the emcee he clearly hears as one step above JAY‑Z—with flows like the one he uses on “That Ain’t Me.” On “Right Above It” and “Bill Gates,” he sounds like he’s trying to go even further than that, aiming past the gods he once measured himself against. Nas once called himself “half man/half amazing,” but Wayne had already answered with “Phone Home,” where he claimed to be a Martian. After collaborating with Nas on Distant Relatives, he doubles down here: not only in the album title, but right from the first track, he states flatly: “I Am Not a Human Being.” So the more you listen, the more echoes you hear of the rhymes and songs he released up through last year. If you try to read this album as a clue toward his next direction, you can spin out the kind of analysis I’ve just been making. But for the real die‑hard fans, this isn’t a record you pick up because you expect some huge, shocking change. If anything, it’s the opposite: you go in expecting no big stylistic leap. You press play, you enjoy what he’s already perfected, and at the same time, your mind drifts to the mixtapes promised for after his release and to what Tha Carter IV might sound like. That, realistically, is how most fans are going to live with this album. — LeMarcus

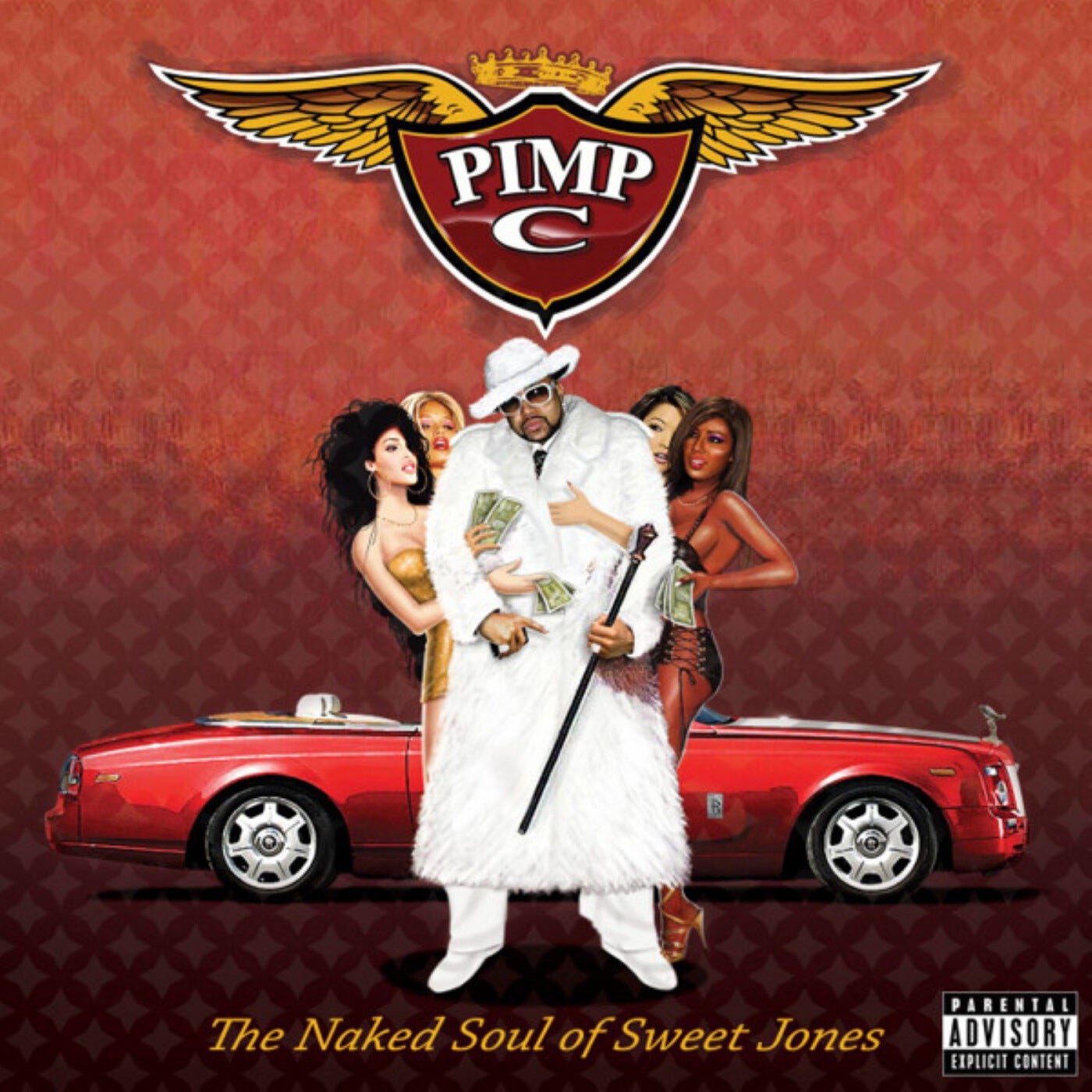

Pimp C, The Naked Soul of Sweet Jones

That cover—built around imagery from the blaxploitation film The Mack—absolutely glows. It suits what turned out to be Pimp C’s third and final solo album. Even in death, he’s still stirring things up. On the intro to the opening track “Down 4 Mine,” he leaves us with this “last will and testament”:

“My first solo album, bitch. I ain’t never had one before. They dropped that other shit while I was in the penitentiary… I got out and dropped that comp on they ass and fucked them up… This is Pimp C starring in The Naked Soul of Sweet Jones.”

And he’s not wrong. His so‑called solo debut, The Sweet James Jones Stories (2005), released while he was locked up, was basically a compilation of previously recorded UGK material, outtakes, and freestyles. The follow‑up Pimpalation(2006) was rushed together right after he got out at the end of 2005 and had the feel of a label project more than a true, from‑scratch solo vision. (Between those two “solo” albums, there’s only one track actually produced by Pimp himself.) So even if you’re not a hardcore UGK head, you can understand the frustration he’s venting here. With that background in mind, The Naked Soul of Sweet Jones—a perfect title, by the way—was supposed to be his first real solo statement, built carefully with him in the driver’s seat. It’s painfully ironic that the album still had to be finished without him. But what we ended up with is a carefully crafted major work that easily blows past The Sweet James Jones Stories and Pimpalation.

Overall, the vibe is very close to UGK’s swan song UGK 4 Life: a lot of the same producers show up—Cory Mo, Steve Below, DJ B‑Do, Mike Dean, David Banner, Mouse, and Boi‑1da, among others—and that gives it a similar feel. There is one obvious misstep: the trance‑rap style of “Colors” really does sound like unnecessary padding, just like the one clear throwaway on UGK 4 Life. But aside from that, the quality level stays high. The album kicks off hard with “Down 4 Mine”, which flips Eddie Kendricks’ “If You Let Me” into a thugged‑out anthem—credited as “Idea Inspired by Scarface,” a credit that’ll hit long‑time fans right in the feelings. From there you get a run of lush, soulful tracks: the sensual “Love 2 Ball,” which quotes Marvin Gaye’s “You Sure Love to Ball”; the gloriously sleazy street‑hustler funk of “Fly Lady”, powered by Jazze Pha’s support; and Texas‑to‑the‑bone cuts like “Made 4” and “Believe in Me,” which lean into that classic Gulf Coast sound.

Boi‑1da shows up on “What Up?”, delivering an unusually melodic, singing‑heavy track that works way better than you might expect from someone known for harder beats. David Banner’s sentimental “Midnight” sits slightly apart sonically, and Mouse’s synth‑banger “Hit the Parking Lot” adds another welcome wrinkle to the palette. Guest‑wise, Bun B naturally steps up on two songs, joined across the album by Rick Ross, Young Jeezy, E‑40, Too Short, Chamillionaire, Slim Thug, Webbie, and more. It’s a stacked cast, but nobody overshadows Pimp; they orbit around the persona he spent his life sharpening. — Reginald Marcel

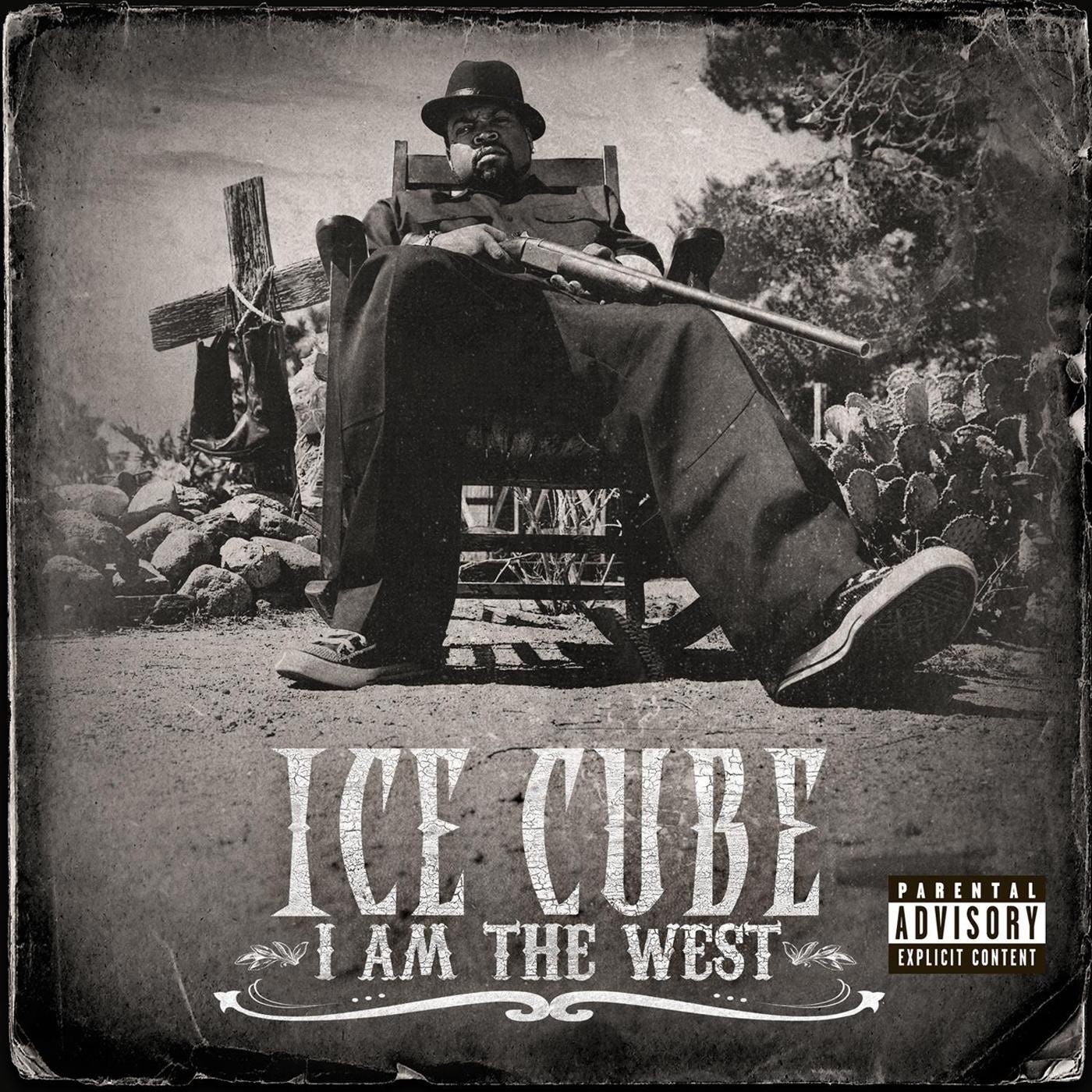

Ice Cube, I Am the West

How did Cube’s notorious friction with younger West Coast rappers actually affect his music? At the very least, you can hear it as a major source of motivation for his first album in two years, and as a chance for him to reassert exactly what kind of OG he is and what that status means. The lectures aimed at the new generation, and the mini‑beef with Dr. Dre that flared up over the lyrics to the advance single “Drink the Kool‑Aid,” all end up serving as the stage‑setting for this ninth solo album. That said, Dre and DJ Quik don’t actually appear here. Instead, the only outside veteran presence is Domino singing the hook on “Life in California”, a track co‑produced by longtime ally Sir Jinx—working with Cube again for the first time in seven years. Beyond that, he keeps the mic within the Lench Mob family: WC, Maylay, Doughboy, and OMG (his two sons). So this doesn’t turn into the kind of bloated old‑guy‑reunion project you might have expected from the pre‑release drama.

On “Your Money or Your Life,” Cube does run through a roll‑call of legends—Dre, MC Ren, Ice‑T, King Tee, and others—in a way that sounds like “Still D.R.E.”‑style solidarity. But by also framing things as a generational standoff, he dodges ending up as just another nostalgic relic himself. What really carries the album is Cube’s own confidence, anchored in a 25‑year career. Songs like “Soul on Ice” and “No Country for Young Men” ride a Dre‑like, sleek G‑funk, but even when the production feels familiar, the details keep it from being stuck in the past. “I Rep That West” comes courtesy of Florida producer Jigg from Swerv’n House, and the mellow G‑funk of “Nothing Like L.A.” is by another Florida team, the Fliptones. That willingness to go outside the traditional West Coast circle and still sound like himself continues the approach he took on his comeback album Laugh Now, Cry Later (2006): West Coast at heart, but not boxed in.

Elsewhere, T‑Mix pops up again, probably thanks to Swerv’n House’s Tony Draper handling marketing. There are also solid beats from names like Bangladesh and DJ Montay, and all of them feel tailored to Cube—thick, heavy, and built around his voice. Hallway Productions, now firmly part of the extended Lench Mob, supply strong, hard‑charging tracks like “Too West Coast”, where Cube stomps over the beat, and “Fat Cat”, another trap‑tinged Sir Jinx production that shows he can update his flow while still giving fans the exact Ice Cube they came for. WC and Maylay bring their usual raw energy, and there’s a sense that Cube is also using this album to introduce the next generation—Doughboy and OMG—without ever giving up control of the narrative. As writer, director, and star, he keeps the flow of the album tightly handled.

So while other West Coast players like Snoop and The Game are out here loudly trying to speak for the entire region—“We Are the West” style—Cube stays locked into a tighter core crew and claims the title I Am the West for himself. In a way, that’s perfectly fitting. With a catalog full of genuine classics, this was never going to be his greatest album, and on the charts it actually turned out to be one of his weaker showings. But honestly…so what? As a late‑career statement of who he is and how he sees the coast, it’s impressively stubborn and self‑assured. — Nehemiah

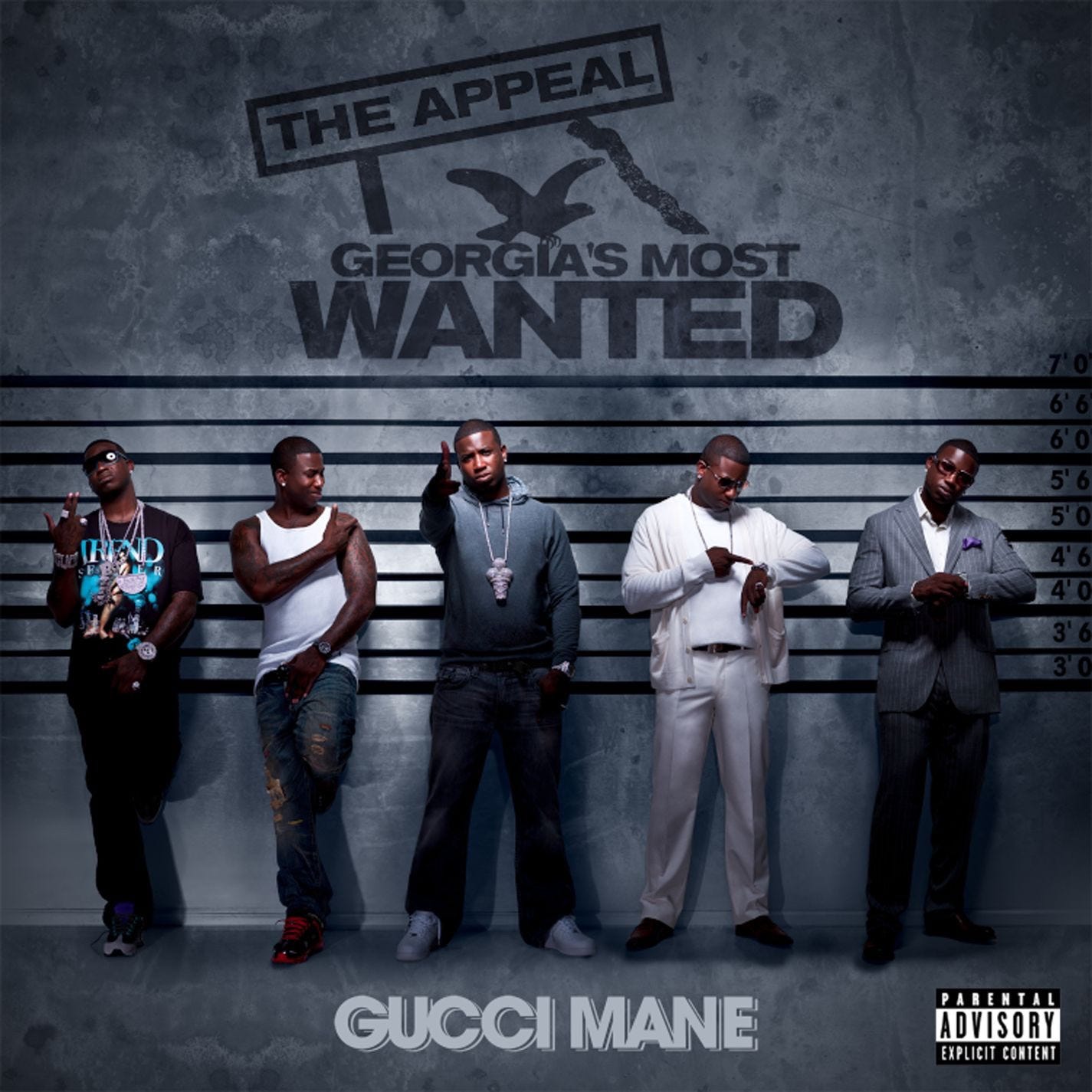

Gucci Mane, The Appeal: Georgia’s Most Wanted

When The State vs. Radric Davis dropped, Gucci himself was in jail—a pretty miserable situation, or maybe just a very Gucci kind of “of course this would happen” moment. Even from behind bars, he kept working: in March, he released the mixtape-type album The Burrrprint 2 HD, recording verses over the phone and compiling them with other already‑finished tracks. After his release in May, he changed his label name from So Icey Entertainment to 1017 Brick Squad, and then watched the crew’s prince, Waka Flocka Flame, break through with a huge debut. Around the same time, a young in‑house producer the crew had been nurturing, Lex Luger, suddenly became a chart fixture. All of that momentum feeds into The Appeal: Georgia’s Most Wanted.

True to form, Gucci’s mixtape grind didn’t slow down either: before this album, he dropped four free download tapes. But unlike a lot of recent situations where the “online promo” flood leaves you exhausted—or where nearly every album track has already appeared on a mixtape—The Appeal manages to avoid that trap. It feels fresh and tight, like someone just sliced a piece straight out of his street life. Gucci had already settled on the concept for The Appeal by around May, and in one interview, he said he definitely wanted the word “Appeal” in the title. The term can mean “charm,” but in legal language, it’s about appealing a sentence, which makes sense given his circumstances. Tagging it with the subtitle Georgia’s Most Wanted underlines how deliberately he’s playing up his outlaw image.

Instead of the big, jokey intro that opened the previous album, this one begins with “Little Friend,” featuring Bun B. Somewhat surprisingly, the track is produced by Rodney “Darkchild” Jerkins, who gives Gucci a thick, trap‑styled beat that still carries his polished pop sheen. The chemistry with Zaytoven on “Missing” is exactly as natural as fans would expect, and it feels comfortable hearing Gucci back in that zone. Gucci links up with Swizz Beatz for three songs this time. “Gucci Time”, built around a sample from Justice’s “Phantom Pt. II”, and “Party Animal” both follow directly in the line of his big club hit “Wasted”—perfect, noisy club bangers, complete with the trademark “Burr!” ad‑libs. Gucci just sounds wrong if he isn’t this loud. On “Haterade,” with Pharrell Williams and Nicki Minaj, he gets to show off his gift for sarcastic, side‑eye punchlines.

“ODog”, featuring Wyclef Jean, is the token “reflective life story” track, about looking back on his past and trying to see a future. The theme is corny on paper, but Gucci’s bare, unsentimental way of describing his life keeps it from turning into a Hallmark card, and Wyclef’s bluesy hook matches him perfectly. Then “Grown Man,” with Estelle, closes things out on a quasi‑spiritual note: lines about his life being tested and then “saved by God,” about friends who don’t die easily, and shedding tears for the fallen—it plays like a page out of the Gucci gospel. If The State vs. Radric Davis felt like a wild, almost overstuffed introduction to Gucci’s world, powered by big singles, The Appeal comes off as leaner and more focused. It puts the rapping and the storytelling in the foreground, without losing the sense that we’re listening in on the ongoing saga of one of Atlanta’s great chaos agents. — Brandon O’Sullivan

Chiddy Bang, The Preview

This mini‑album serves as a calling card for a duo made up of a talented MC and a track‑maker who met on a college campus. Pharrell, of the Neptunes, produces the lead track “The Good Life,” which naturally drew a lot of attention, but the other songs are just as percussive, playful, and electro‑leaning, very much in a style Pharrell himself tends to favor. Another signature of the project is the heavy sampling of Brooklyn‑associated indie rock acts like MGMT and Sufjan Stevens. Don’t mistake that for a shallow crossover grab, though. Their whole career trajectory—blowing up on MySpace, signing with a UK‑based indie label, and moving in the same online spaces as Vampire Weekend or Dirty Projectors—lines them up more with Brooklyn indie bands than with a traditional rap come‑up. They’re already stars in the UK, and that mix of indie sensibilities and chart presence makes them a duo to watch. — Oliver I. Martin

…And two more collaborative albums written by one of our good buddies.

Apollo Brown & Boog Brown, Brown Study

Brown Study pairs Detroit producer Apollo Brown with a gifted MC, Boog Brown. Apollo works firmly in a traditional East Coast style built on sampling, digging in crates for vinyl fragments, and stitching them together into chunky, funky beats. He’s not quite at the level where you’d directly compare him to Pete Rock or DJ Premier, but he isn’t just pounding away in grimy mode either—there’s enough softness and air in his sound to keep things balanced. Boog Brown doesn’t have the instantly recognizable eccentricity of a Missy Elliott, but she rides rhythms with the calm authority of someone in the Bahamadia school. Her feel for timing is excellent, and on “Friction” she goes bar‑for‑bar with Detroit’s own Invincible—one of the sharpest MCs around—without getting overshadowed. That track alone shows she can really rap. The downside is that a tendency you often see with women MCs in a macho hip‑hop environment is that, in pushing back against that machismo, she sometimes feels like she has to be harder than necessary, fronting extra aggression to prove a point. That’s why tracks like “Carpe Diem,” with its gentler, more embracing mood, feel like such a relief—you can just relax and enjoy how well her voice and Apollo’s warm, dusty beats fit together. — Harry Brown

Skyzoo & !llmind, Live from the Tape Deck

Within the Justus League orbit, Skyzoo has become second in stature only to Little Brother. On this collaboration, he links up with !llmind, an Asian‑American producer who’s been doing steady work around the Justus League / Duck Down axis for years. This is actually !llmind’s first time handling full, top‑to‑bottom production on an album, and he makes the most of it. You can hear 9th Wonder’s influence in soulful tracks like “#Allaboutthat” and “Barrel Brothers”, but !llmind also shows new sides of himself. “Speakers On Blast” sounds like it grew out of Ron Browz’s “Pop Champagne” era—a big, glossy, club‑ready record—while “The Burn Notice”, with its snarling electric‑guitar riff and Heltah Skeltah feature, pushes into louder, more chaotic territory. As a debut turn as sole producer, it’s more than solid. The album isn’t flashy at first listen, but it seeps in over time—the same slow‑burn appeal that Skyzoo’s first album (The Salvation) had. In that sense, Live from the Tape Deck works perfectly as a “1.5th album” for him: not the formal follow‑up, but a fully satisfying project that keeps his name hot while he lives more life to write about. — Harry Brown